On March 20, 1995, two physicists, an artificial intelligence researcher, an engineer, and a heart doctor entered the Tokyo subway system at the peak of morning rush hour. Each of the men carried two small plastic bags wrapped in newspaper and an umbrella with a sharpened tip. After boarding five different trains, the scientists dropped the plastic bags at preordained stations and punctured them with the tips of their umbrellas before exiting the subway to rendezvous with their getaway drivers. As these scientists were whisked away to a hideout, the deadly sarin gas contained in their packages began to permeate the air in the subway tunnels.

By the time the air had cleared, 12 subway commuters were dead and over 1,000 others were injured through exposure to the potent nerve gas. It remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in Japanese history.

Videos by VICE

On Friday, seven leaders of Aum Shinrikyo, the doomsday cult formed in the late 80s that was responsible for the 1995 Tokyo sarin gas attack were executed by hanging. Among the seven were Shoko Asahara, the leader of the Aum cult, Yoshihiro Inoue, the mastermind of the subway attack, Seiichi Endo, the cult’s lead scientist, and Masami Tsuchiya, the group’s chief chemist. The actual perpetrators of the chemical attack are still on death row in Japan.

Although human rights groups like Amnesty International condemned the executions, which are carried out without advance warning in Japan, some attack victims only wish they had been notified about the executions ahead of time.

“When I think of those who died because of them, it was a pity (my husband’s) parents and my parents could not hear the news of this execution,” Shizue Takahashi, the widow of a Tokyo Metro employee who died in the 1995 attacks told CNN. “I wanted (cult members) to confess more about the incident, so it’s a pity that we cannot hear their account anymore.”

Aum Shinrikyo was a religious cult for the internet age. Its members blended yoga, terrorism, murder, chemical weapon production, arms manufacturing, and software development to create a multinational LSD-fueled monster. This is the story of Aum’s creation, the role of science in its terrorist activities, and why the cult’s vision never really died.

Bioterrorists and Software Developers

Formed in 1984 by the pharmacist Chizuo Matumoto, who would later assume the name Shoko Asahara, Aum Shinrikyo was originally dedicated to yoga and meditation. Shortly after its founding, however, Asahara believed he had been selected by the Hindu god Shiva to create a utopian society and set about trying to elect members of his ascetic cult to the Japanese government. When Aum members only managed to secure a few hundred votes in the 1990 elections, Ashara told his reclusive followers that the group should instead focus on the violent overthrow of the Japanese government.

Ashara’s plan began with an attempt to create large reserves of botulinum, a neurotoxic chemical produced by bacteria. To produce the neurotoxin, Seiichi Endo collected soil from the Ishikari River and allowed the bacteria to ferment in large containers at a compound run by the group. Endo managed to produce nearly 50,000 liters of fermented sludge, but since the sludge hadn’t been purified, initial tests showed it induced no toxic effects. Nevertheless, in April 1990 members of Aum loaded the sludge into three spray trucks. They drove by two US naval bases, Narita airport, a Japanese government building and the Imperial Palace while spraying the sludge from the trucks, but the ‘attack’ didn’t induce any negative effects in the people near those areas.

The early years of Aum Shinrikyo were defined by failed chemical attacks. In 1992, Ashara, who now believed he was Jesus, and some of his followers traveled to Zaire in an attempt to acquire Ebola samples, but returned empty handed. The following year, the group again tried to launch an botulinum attack at Prince Naruhito’s wedding using a spray truck, but like the first attack attempt the neurotoxin hadn’t been activated. Shortly thereafter, Aum members tried to launch an anthrax attack by spraying the bacteria from the roof of its headquarters using a fan and in drive-by attacks with spray vehicles. In both instances, the attacks failed due to using unusable strains of the anthrax bacteria.

At the same time, however, Aum carried out a string of murders against those it considered to be enemies or members of the cult that tried to defect. Although the mysterious circumstances of these murders brought increasing public scrutiny to the group, police couldn’t tie the murders to Aum and the negative attention didn’t dampen its popularity. By 1992, Aum Shinrikyo had a net worth of more than $1 billion raised from charging exorbitant fees from its roughly 20,000 members in several countries, including the US, Australia and Russia.

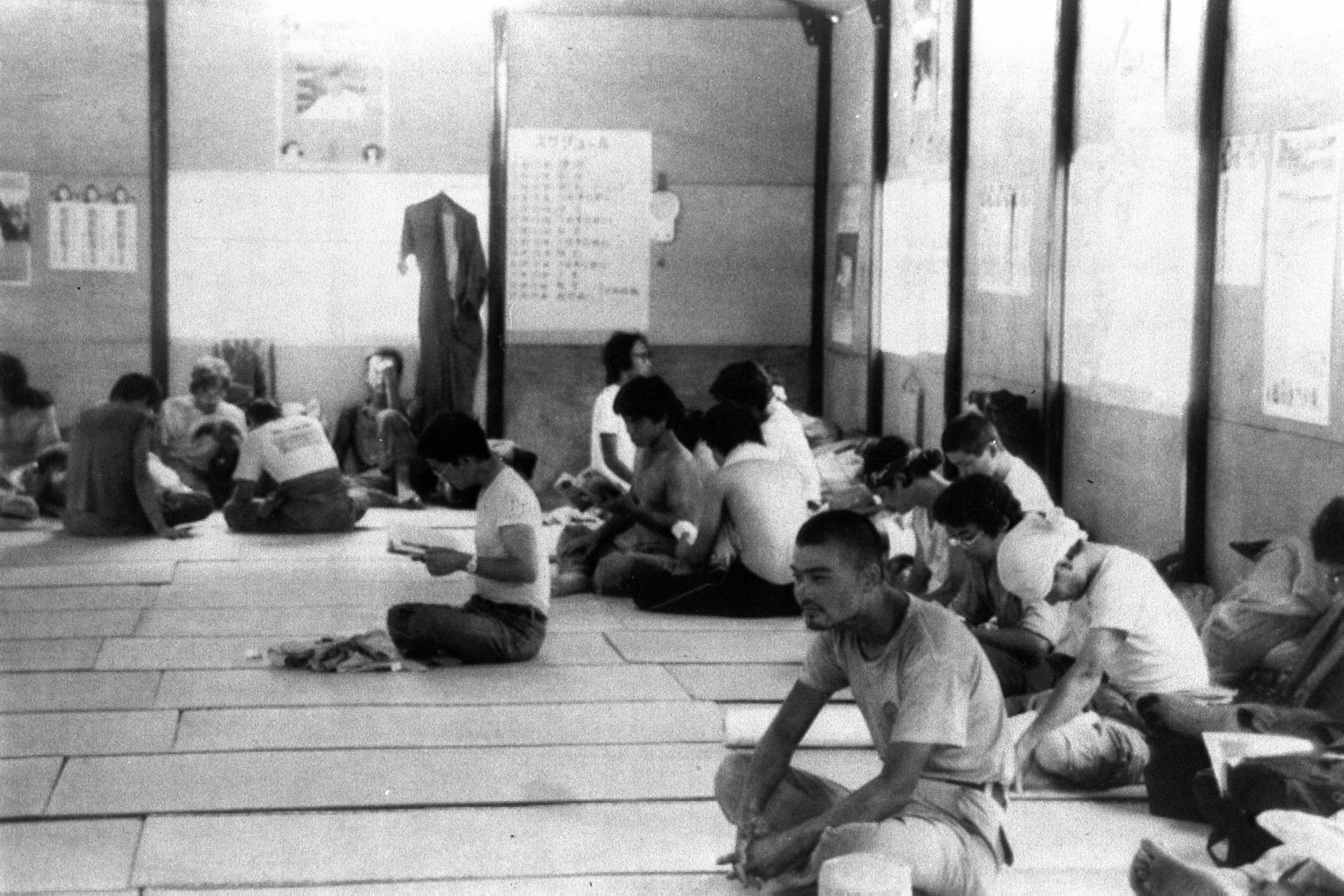

Many of these members were highly educated students and wealthy businessmen. According to a 1996 Wired feature on Aum, many of the cult’s recruits were “the otaku—Japan’s version of computer nerds—technofreaks who spent their free time logged on to electronic networks and amassing data of every type.” As such, Aum relied heavily on science fiction imagery and grandeur to pedal its vision of nuclear armageddon and techno-redemption to attract new members.Indeed, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy served as a sort of “bible” for the sect, which also aspired to build a utopian community of scientists.

Read More: A Suicide Cult’s Surviving Members Still Maintain Its 90s Website

In 1994, Aum orchestrated its first successful bioterrorism attack by releasing clouds of sarin gas near the homes of judges who were presiding over a real estate lawsuit brought against the cult in Matsumoto. These attacks resulted in eight deaths and injured several hundred others. After years of failures, the chemists working at the cult’s Ministry of Science and Technology demonstrated they could produce large quantities of active nerve agents. As it would turn out, however, this was just the beginning.

Shortly after the Matsumoto attack, Aum’s chief chemist Masami Tsuchiya produced around 200 grams of VX gas, a militarized nerve agent that is more potent than sarin—exposure to only a few dozen milligrams is enough to kill a human adult. In September of 1994, the initial batch of VX created by Tsuchiya was used to kill 20 Aum members that had left the cult as an experiment to demonstrate that the VX gas had been successfully synthesized. In the months leading up to the Tokyo subway attack, Aum stepped up its VX attacks, spreading it on car door handles, injecting it into keyholes and spraying it from syringes onto lawyers, members of Aum victims groups, rival religious leaders and other dissident cult members.

As the members of Aum Shinrikyo made preparations for a large-scale subway attack using sarin gas it had manufactured at a massive facility at the base of Mt. Fuji, Japanese police were building a case against the religious group and preparing for a raid. When word of the impending raid reached Asahara, he ordered the Tokyo attack to be carried out ahead of schedule on March 20. Two days after the attack, Japanese police arrested Ashara and hundreds of Aum cult members and raided the cult’s headquarters at the base of Mt. Fuji. There police found the entrance to a massive sarin production facility hidden behind an alter, a stockpile of sarin precursors that could produce enough of the neurotoxin to kill 4 million people, a Russian military helicopter, explosives, labs equipped to manufacture LSD and meth, millions of dollars in US cash and gold, and several prisoners being held in cells.

The Future of Aum

By 2004, 13 members of Aum Shinrikyo had been sentenced to death and five members given life sentences for their roles in the sarin attack on the Tokyo subway and various individual murders perpetrated by the group. 80 other members of the cult were given prison sentences of varying lengths. Asahara’s execution was postponed in 2012 after two wanted members of Aum were apprehended in Japan. After years of delays due to repeated appeals for re-trials, on Friday morning, seven of the senior members of Aum were executed by hanging with no advance notice given to the public.

Despite the sordid legacy of the Aum Shinrikyo, the group continues to exist, albeit in a nominally different form. Since 2000, the organization has gone by the name Aleph and renounced the violent program of Aum. Still, in 1999, the Japanese government authorized the Public Security Investigation Agency to carry out investigations of the group’s activities across the country as it saw fit. Despite the scrutiny and public protest, however, Aleph members still follow Asahara’s teachings and appear to have deep ties in the Japanese science and technology sectors.

In 2000, it was revealed that Aum-affiliated computer companies had developed software for at least 10 Japanese government agencies and over 80 major Japanese corporations. According to the New York Times, this raised concerns that Aleph may have had access to sensitive government information and computer systems. Following the report, many Japanese companies immediately suspended use of software developed by Aum-affiliated companies out of fear that it would be used for cyberterrorism. In 2002, The Guardian reported that Aum also “enjoys a huge following within Japan’s nuclear establishment, which is riddled with believers from millennialist sects.”

Today, Aleph is seen as less of a threat than Aum once was, but it is still an active religious organization that has seen a resurgence of interest in Japan and Russia. In 2016, authorities in Montenegro broke up a conference organized by Aleph in the country after the hotel that was hosting them reported that some of the attendees, most of whom were Russian, showed “signs of ritualistic injury.” In Japan, the organization continues to recruit young people through yoga sessions. Last year, Aleph was raided by Japanese police over illegal recruiting practices, including taking thousands of dollars in membership fees without requiring members to fill out requisite paperwork and failing to disclose the organization’s links to Aum.

In the lead up to Friday’s execution of top Aum members, Japanese police searched 16 facilities related to Aum, including some run by Aleph. Following the execution, a “senior official” at Tokyo’s Metropolitan Police Department said the agency was stepping up security at some locations out of fear that some of Asahara’s followers may try to retaliate for his death.

The story of Aum is as strange as it is tragic, but it serves as an important reminder about the ambiguity of scientific advancement and the democratization of high technology. Although scientists pride themselves on their objectivity and ability to stick to evidence, Asahara demonstrated that they are just as susceptible to being lead astray as anyone else. Moreover, as the cost of sophisticated technologies continues to decrease, it becomes easier for bad actors to get their hands on these same technologies and use them for destructive ends. In the age of deep fakes, gun-toting drones, and freely available militarized malware, the next incarnation of Aum might not be so easy to stop.