The sandwich so special it shares its name with the French capital contains only three ingredients: ham, butter, and baguette. Simple, to be sure, but le Parisien has a long history that continues even today. As of 2014, the French were buying 1.28 billion ham-and-butter sandwiches every year.

It was in the 19th century that the first Parisien or ” jambon-beurre” (literally: “ham-butter”) appeared in Paris’ les Halles covered market sector, which was then dubbed the Belly of Paris. Market workers placed Paris ham—a local, wet-cured specialty charcuterie—between two hearty slices of country bread smeared with butter for a protein-rich snack to help keep them going through lunch.

Videos by VICE

Round country bread was soon eclipsed by the baguette, a trend that is explained by all manner of urban legends; from Napoleon inventing the long, skinny loaves so that his soldiers could carry them down the leg of their pants, to the foreman in charge of building the Paris metro begging local bakers to produce bread that could be ripped rather than cut to keep workmen from bringing knives into the underground tunnels and fighting one another. However the baguette was invented, by the 1920s, it had become the bread of choice for the Parisien: split lengthwise and buttered, it was the perfect vessel for a few slices of Paris ham.

READ MORE: There’s a Scientific Reason Why Baguettes Taste Better than Sliced Bread

But quality soon become a problem: Even in the capital of gastronomy, industrialization hit the culinary world, something that affected the key components of the jambon-beurre.

Bread had been standardized in one way or another as early as the French Revolution; with the imposition of a legal price for bread, bakers seeking to increase profit margins had only one option: decrease ingredient quality.

The baguettes of the 80s and 90s were bland and lacking in texture, and the moniker of traditional Paris ham ( jambon de Paris) soon came to refer to every plastic tray of sliced wet-cured ham in the grocery store.

A sandwich with only three ingredients was sure to suffer. “Martyrized by the agroalimentary industry, this culinary emblem became a sort of French junk food,” says food critic François-Régis Gaudry in a 2015 documentary entitled Jambon-Beurre.

But in recent years, this trend towards industrialization has been turning around.

The baguette de tradition, or “traditional baguette,” first graced the capital in 1993 as a counterpoint to mass-produced bread. Made with a sourdough starter and formed by hand, it costs about 40 cents more than a standard baguette, but it makes a world of difference. And in 2005, chemist Yves Le Guel bought the last true Parisian ham company in Paris, intent on making authentic charcuterie of the highest quality.

While the first mention of Paris ham appears in 1793, Le Guel notes that Paris ham is actually a tradition that goes back as far as the Parisii Gauls, the proto-French Celts who occupied what is now Paris before the arrival of Julius Caesar. “They were already making hams from wild boar and bear,” he says. “And then in the 1700s, someone finally established official specifications for Paris ham.”

Le Guel follows these specifications of yore: real vegetables and spices infuse the brine, which is added to the ham via an arterial pump system. The hams are then cooked for nine hours in low heat. The result is free of any additives or preservatives (save a small amount of nitrite salt to ward off botulism), and today, it’s one of the only hams that Paris’ top chefs will even consider serving. Of the 500 artisanal hams that Le Guel and his team produce by hand every week, 10 percent are used to make Parisien sandwiches in the capital.

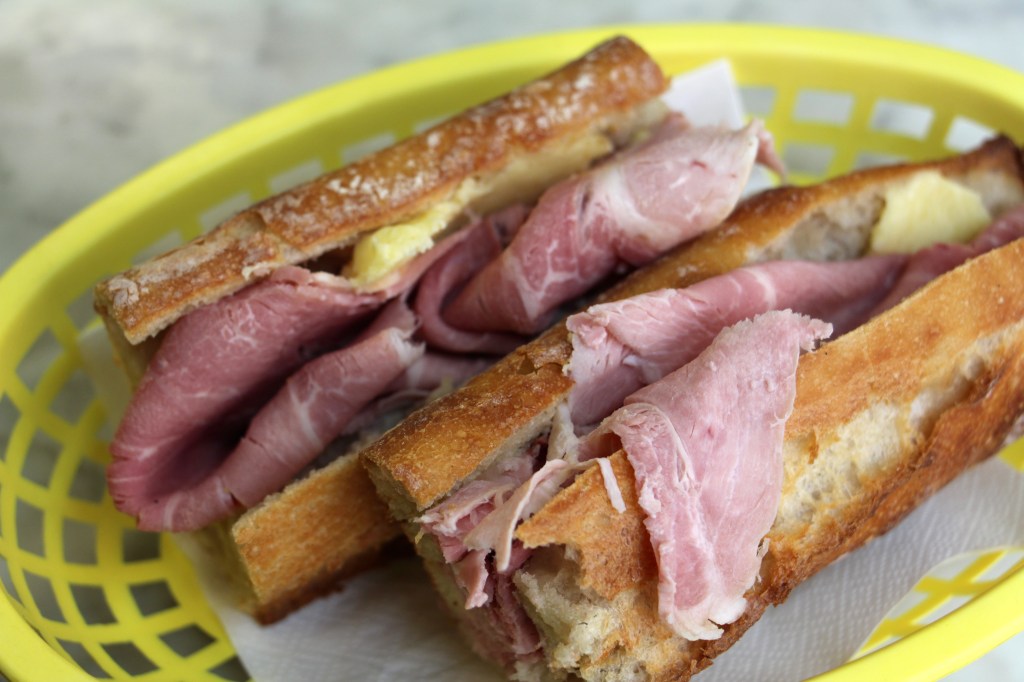

The Parisien at Chez Aline, featuring Le Guel’s ham, Norman salted butter, and Landemaine baguette tradition, is regularly recognized one of Paris’ best.

“The bread is exactly how I like it: a traditional baguette that’s crisp—not overcooked but still golden,” says Chez Aline owner Delphine Zampetti of the baguette made by Rodolphe Landemaine, a former student of Paul Bocuse. “I think that makes all the difference.”

So, too, does the fact that every sandwich is made to order, something that you won’t find in many of the over 30,000 bakeries throughout the capital that prepare these sandwiches early in the morning to sell to everyone from professionals to students on their lunch break. But even though at 5 euros a pop, Zambetti’s sandwiches are about a euro-fifty more expensive than the average in Paris (which was €3.48 in 2016), she’s getting a fine amount of business.

“I think people are paying closer attention to what they eat, and they’re realizing that it’s not that much more expensive to buy something that’s of good quality,” she says. “I think people are thinking about food differently now.”

WATCH: How to Make a Croque Madame with Kris Morningstar

“There was a bit of time when we lost that,” says Le Guel. “Now, we’re coming back to a higher demand for quality. People are sick of being cheated and buying poor quality products.”

Michelin-starred chef Yannick Alléno agrees. He decided to place the sandwich on the menus of his Terroir Parisien restaurants (currently in redevelopment), where, he says, “We wanted to recreate the spirit of a welcoming, convivial Parisian bistro while highlighting the oft-forgotten culinary heritage of the Ile-de-France region.” His sandwich was made with Le Guel’s ham and baguette from Meilleur Ouvrier de France baker Frédéric Lalos.

“We served the sandwich plated,” he says. “But only at the counter, as a quick snack, or else we offered it in a paper bag to go.” Revisiting this classic is a wink at Alléno’s own childhood.

“I grew up in the suburbs of Paris,” he says. “My mom made us little ham-and-butter sandwiches all the time. It was an easy, nourishing snack, and moreover, we loved it. It represents movement, peripateticism, the absence of constraints when a meal is eaten on the go. It’s the perfect, flavorful snack.”

His fellow Michelin laureate Eric Fréchon also serves the sandwich at his restaurant Lazare in the train station of the same name.

“This sandwich is really emblematic of Paris,” says Fréchon. “Lazare is in the heart of the train station; we needed a very good sandwich, and ham-and-butter was the obvious choice.”

At 7.90 euro each, his sandwich has surpassed its peasant origins to become a true gourmet masterpiece in one of the epicenters of Parisian daily life.

“A sandwich doesn’t always have to be eaten on the run, between two meetings,” says Freçhon. “You can have a seat, take your time, and really savor it.”

In the midst of the hustle and bustle that characterizes so much of modern life, it is perhaps here, in the emblematic sandwich of Paris, that Parisians have found their respite.