“Let me just see if we got any answers to the relays.”

“‘Whiskey Papa Three Radio’—listening,” said Ángel Vázquez over radio.

Videos by VICE

When Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico with devastating force, making landfall on September 20, Vázquez was hunkered down at home. On a normal day, he would’ve been at work; not far away, at the Arecibo Observatory, the world’s second-largest radio telescope. There, Vázquez is Director of Telescope Operations.

The 1,000-foot-wide dish has beamed SETI messages into deep space, and detected far-flung planets. Today, some of the only radio signals coming from Arecibo Observatory belong to Vázquez, and concern purely terrestrial matters.

After the storm barreled through the island, the Universities Space Research Association, which operates the facility out of Maryland, lost contact with its crew there. But within 36 hours, Vázquez could be heard on the airwaves, thanks to a ham radio rig in his house.

Everyone who sheltered at the observatory was safe, he said. A 96-foot-long antenna had crashed into the enormous dish, leaving gaping holes. One smaller dish had been lost.

*

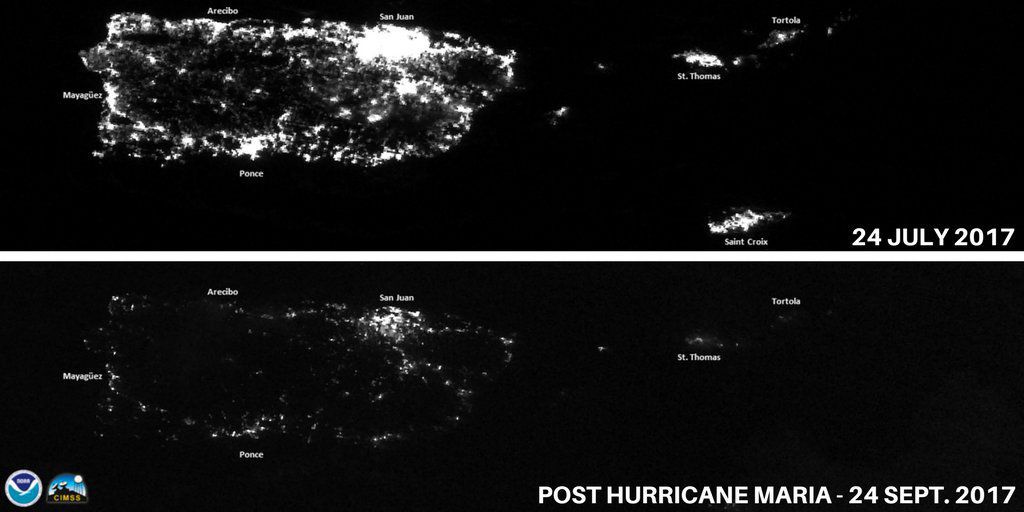

The Category 4 tempest killed at least 10 people in Puerto Rico. An estimated 700 more were rescued from deadly floodwaters. Officials at the government-owned power corporation said it could take months to re-establish electricity across the country.

President Trump’s response to the crisis has been perfunctory. Over the weekend, for example, he tweeted 17 times about professional sports. While Puerto Ricans are suffering, he’s made ill-timed comments about the island’s debt.

Food, water, fuel, and battery power are running out. “If anyone can hear us… Help,” pleaded San Juan’s mayor, Carmen Yulín Cruz, on Saturday.

Most Puerto Ricans are just trying to reach family members. Few have access to Wi-Fi hotspots or electrical outlets. Sustained winds of 155 mph obliterated 95 percent of Puerto Rico’s wireless cell sites, leaving much of the country a deadzone. In the past week, Puerto Rico’s government has received more than 110,000 outside calls, many, no doubt, from panicked relatives.

Remote places like Arecibo, near the western part of Puerto Rico, were particularly hard-hit. Here, the only reliable mode of communication is radio. And amid the silence, a determined network of radio hobbyists, affectionately called “hams,” is helping communities make contact.

“I did get ahold of Shirley, she’s very happy about hearing about Tony. And I talked to Karen and told her about Phil. You can relay to Phil that she’s also going to tell Phil’s mother that he’s doing fine,” piped Greg Dober, a volunteer ham radio operator in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, returning Vázquez’s call.

“Much obliged there, Greg. Much obliged,” Vázquez replied.

*

“We do the things that first responders can’t because they’re so busy. We can relay almost any information. The most important thing is getting health and welfare information to a place where relatives can access it,” Tom Gallagher, CEO of the American Radio Relay League (ARRL), told me.

Stalwart volunteers for ARRL, a national association for ham radio enthusiasts, are providing real-time dispatches from the Caribbean. A tactical team of 50 bilingual hams, recruited by the Connecticut-based ARRL, will be deploying to Puerto Rico for three weeks to assist the American Red Cross. Their primary objective will be submitting survivor information to agency’s Safe and Well system, which lets people know their loved ones are safe.

Ham radio is an older technology, archaic by some modern standards, but highly customizable. Hobbyists must pass a test to obtain a license, so the term “amateur” is something of a misnomer. As of 2015, there were 726,275 hams in the US, and six million worldwide.

Operators use radio transceivers to talk over short or long distances, and generally never for commercial reasons. In the states, the Federal Communications Commission allocates frequencies, or bands, that hams can use, and a general rule of thumb is: lower frequencies at night, and higher frequencies during the day, depending on solar conditions.

These networks are remarkably resilient in bad weather, with the exception of solar storms. (During Hurricane Irma, a massive solar flare temporarily disrupted the communications of Hurricane Watch Net, a weather ham radio group.)

Hams can send a range of information, from voice transmissions, to Morse code, to file transfers, over different protocols. Some operators use digital modes to send emails or, in Puerto Rico’s case, lists of names—up to 4,000, according to Gallagher—from local shelters like the American Red Cross’ to families in the states.

Hams have a long history of showing up when disaster strikes, and less nimble government agencies see them as a resource on the ground. FEMA and NOAA often coordinate with groups like ARRL to bounce information to and from local communities.

After the 9/11 attacks, hams helped to transmit messages when cellphone networks were overloaded. When Hurricane Iniki flattened the island of Kauai in 1992, operators relayed critical weather reports after NOAA’s own radio capabilities failed.

“The territories organized regionally, down to almost a county level, for emergency comms,” Gallagher said.

“Just before Irma arrived in the Virgin Islands, our section manager [there] called headquarters and [requested additional radio equipment]. One of FEMA’s contractors picked the stuff up and took it down to Saint Thomas. Equipment went around the island and to the emergency broadcast station we have there. I’m grateful for that.”

Entire neighborhoods, like Fatima on the northern coast of Puerto Rico, were unreachable after the storm hit. The status of a nursing home there, authorities said, was of particular concern. And in the city of Guayama, where a five-story pile of toxic coal ash sits beneath floodwaters, there is an urgent need for ground reports.

Puerto Rico’s governor, Ricardo Rosselló, said communication had been established with all municipalities on Monday. But it’s unclear if that includes smaller communities as well.

“In a disaster, people run to their phones which can overload circuits. The public often doesn’t realize the landline and cellphone service providers can only handle a small fraction of their clients at any given time before becoming overloaded,” Ken Gilliland, network manager for Salvation Army Team Radio Network (SATERN), told me.

Ham radio helps to forecast weather, too, since even the most sophisticated meteorological technology has its limits. When storms strike quickly, hams offer eyewitness reports and on-the-ground measurements. Data like wind speed and ocean conditions can improve the accuracy of hurricane outlooks.

This is why radio groups like HWN worked directly with the National Hurricane Center during Hurricanes Maria, Irma, and Harvey. The National Weather Service has its own network of spotters called SKYWARN that activates during severe storms.

*

“Yesterday was the first I spoke with [Vázquez]. The back of the eyewall had just passed, and gusts were still at 80 mph,” Dober, the Pennsylvania operator, told me last Thursday.

“He did what I expected, which was to create a list of contacts from the folks [at Arecibo Observatory] and have them relayed into the states today. I made about 10 calls for him. Each call was met with happiness,” he added.

Dober is one of many stateside operators manning the airwaves. He’s been a ham for nearly 30 years, a hobby he picked up after working on the Army’s Military Auxiliary Radio System.

In a single day, Dober says he’s counted more than 500 messages passed from Puerto Rico to US operators. One ham he spoke to in Mayaguez said the local hospital was running out of fuel for generators—”he noted it is becoming dire”—and asked Dober to submit a plea to FEMA.

Other times, family members on the mainland have put in requests for situation reports. “I have sent some emails to Florida operators to find out the conditions in Ponce, as I have a few people that want to know,” Dober said. (“Latest news I got via email [regarding Ponce],” he told me a day later. No casualties, and limited communications. The Ponce airport will be prioritizing military and relief cargo. “Great example of the meshing of old tech and new tech.”)

But as ham volunteers reach critical mass, Dober warns that frequencies can become overcrowded. The Caribbean Emergency and Weather Net requested a “clear frequency” last week on 7.188 and 3.815 MHz to handle traffic from the hurricane-battered island of Dominica.

Likewise, amateur radio groups discourage hams from self-deploying to the Caribbean. Just like any disaster relief, even the best intentions benefit from coordination.

*

Back in Arecibo, Vázquez was having trouble with his generator, making reports sporadic. As of Monday, though, the observatory had received a satellite phone, mostly restoring communications. There are remaining staff who have not yet made contact.

“Ángel would have no info yet on any recovery, and I don’t think any of the people associated with the observatory have been thinking about that,” Jim Breakall, who is an electrical engineering professor at Pennsylvania State University, told me.

Breakall is one of the hams who’s been in contact with Vázquez recently. “They are just mainly worried if everyone is safe,” he added. The Universities Space Research Association has also been in contact with Vázquez via radio.

One of the optical buildings has apparently lost a roof, but the damages to the 1,000-foot-wide dish “will be a big setback,” Breakall said.

*

President Trump has yet to visit the Caribbean, and spent much of this weekend taunting professional athletes on Twitter. US Navy and Marine Corps teams were deployed on Monday after the White House was criticized for its muted public response to the disaster.

Puerto Rico’s governor has repeatedly asked for a greater federal response to the humanitarian crisis. “Puerto Ricans are Americans,” said Rep. Nydia Velazquez (D-NY). “We cannot and will not turn our backs on them.”

Before Hurricane Maria hit, Puerto Rico had just begun the restructuring process for its $70 billion debt. The US Virgin Islands was facing its own financial crisis, having the largest per capita debt load of any US territory or state.

No amount of pro-bono relief can step in for the federal aid. But that hasn’t stopped hams from trying.

“The British Virgin Islands are so close to us that we outta find out what our sister societies think. Maybe we can help the Brits and the French by virtue of our proximity,” Gallagher told me.

“And I’ve told volunteers that if they want you to unload blankets at the shelter, you do that too.”

This story previously stated that some ads are allowed on amateur radio frequencies, and has been corrected to reflect that ads are generally not allowed.