Happy hardcore is maybe history’s most divisive dance music movement.

Three decades since its birth, the genre still inspires either elation (the comments under happy hardcore YouTube mixes are as joyful as a double-drop come-up) or pure disdain. Mind you, there’s one thing any bystander has to agree on: happy hardcore is nothing if not entertaining.

Videos by VICE

The genre has its roots in the early-90s rave explosion and that scene’s breakbeat hardcore sound, which fuelled countless illegal parties off Britain’s A-roads. As rave came of age, it fragmented into various specific sounds; towards the middle of the decade, breakbeat purists skanked off through thick clouds of weed smoke and into the emerging jungle scene, while another set cranked up hardcore’s tone and tempo to deranged new levels, birthing the music we know today as happy hardcore.

If jungle found its most fertile creative turf in the cityscapes of London and Bristol, happy hardcore was forged in the mid-90s suburban humdrum of areas like Essex, Northampton and the north and south coasts. Perhaps in part because of its lack of big city cachet, the passage of time has not been kind to happy hardcore: most mainstream dance music gatekeepers continue to ridicule its surreally saccharine spirit and blood-curdling BPMs.

Still, the genre has managed to keep rearing its head – first in the mid-2000s, as trance revitalised the happy hardcore sound, and more recently through its impact on the global EDM movement. Twenty-five years since the advent of happy hardcore, we spoke to the people who have been there along the way.

1986 – 1992: DJs Take Control

Matthew Nelson, AKA Slipmatt (DJ, producer, founding member of breakbeat hardcore group SL2): John Lime [SL2 co-founder] was the only kid in my class into music in the way I was. In 1986, he had a cassette of Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body”. It sounded totally different to anything we’d heard before. From there, we were focused on mixing hip-hop with early house, creating that UK sound.

Paul Clarke, AKA DJ Dougal (DJ, producer): When I was 15 I did my work experience at a shop called Subtronic in Northampton, which just happened to be setting up speakers for one of the first [pioneering promotion company] ESP events at a club called Castaways. At the time it was still acid house – it wasn’t even called hardcore. I remember the record the DJ, Neil Parnell [Tronik Youth], started with: 808 State’s “Cubik”. I knew my life had changed forever. I started doing paper rounds to save up for decks.

Stacey Beetson (ESP Promotions and Dreamscape co-founder): Myself and Murray [Stacey’s late husband] were both going out partying a lot. Murray teamed up with a guy called Craig Campbell, and that soon grew into the Milwaukee’s club [night in Northampton] – that’s when the ESP Promotions name emerged. There used to be queues round the block – it was an absolutely mental party. Because it was so isolated the sound was booming and the bass was just outrageous.

Slipmatt: I debuted SL2’s “DJs Take Control” at the first [iconic rave event] Raindance, which my brother launched in Easter, 1991. I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s done what I wanted it to do.’ I played it at the next Raindance six weeks later and it absolutely tore the roof off. Then the phone started ringing. There were about eight different deals on the table for SL2 at one point. A few months later we were at number 11 in the charts and on Top of the Pops. I don’t think the Essex posse had been on TV too much before that.

Stacey Beetson: Murray being Murray, he wanted to progress, so we teamed up with a guy called Steve Donnelly for the first [legendary rave] Dreamscape. He was from Milton Keynes, so that’s how we found the [iconic rave venue] Sanctuary.

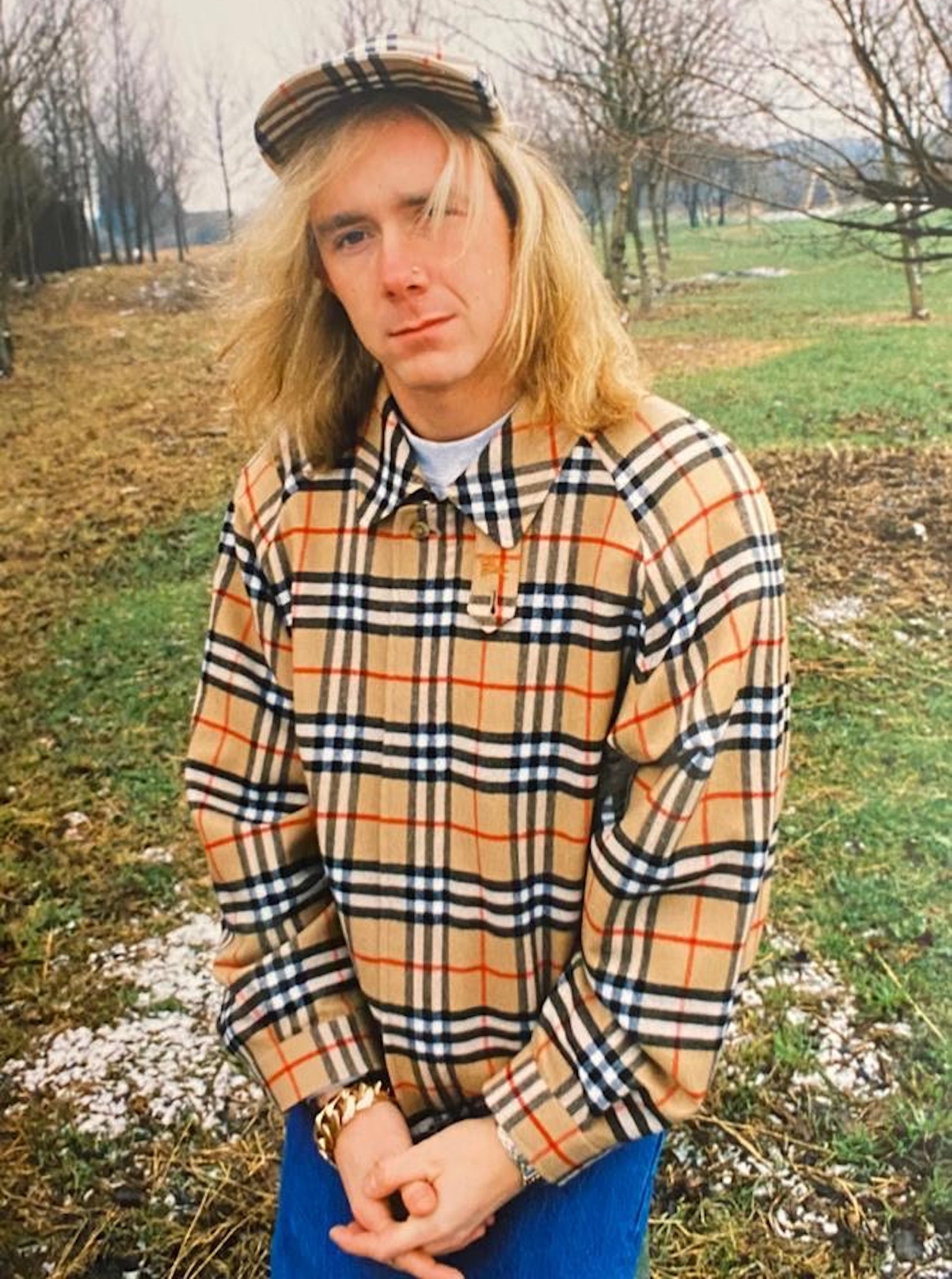

DJ Dougal: I’d only played for Murray about four times when he said, “I’ve got this huge warehouse in Milton Keynes. You’re going to be warming this party up.” I didn’t even have a DJ name. I had long hair, so everyone at school was like, “It’s got to be Dougal, like [the character on the kids’ show] Magic Roundabout.” Seeing my name on that first flyer was a very special moment.

Richard Marlow, AKA MC Marley [pioneering MC): I went to clubs with my school mates, Ramos and Supreme, in Portsmouth. Before I knew it, every Friday night they’d be off DJing and I’d be attempting some form of MCing. Back then, it was illegal raves – I remember lots of crazy parties in the New Forest. Then, in the early-90s, raves like Dreamscape and Helter Skelter emerged. Murray invited us to play at Dreamscape – that’s where it all started. If you listen to our early Dreamscape sets, it’s that original wave of rave. Back then, Carl Cox and Grooverider were playing the same music. Then that split happened, where half of the scene went towards what would become happy hardcore, and the other half became junglists.

1993 – 1995: ‘It changed my life overnight…’

Slipmatt: My forte was playing the more uplifting, hands-in-the-air stuff. By 1992, some rave was going very dark and breakbeat-y. It reflected the drugs at the time. So I came up with “SMD 1”. That was that. It absolutely flew out. I still get asked for it now.

MC Marley: When Slipmatt made “SMD 1”, that’s when it became happy hardcore. From there, you had your happy hardcore DJs and your jungle DJs. Slipmatt was the first. He was the truest pioneer.

Ian Hicks, AKA DJ Hixxy (DJ, producer, co-founder of the Raver Baby record label and the “Bonkers” compilation albums): I wouldn’t really call “SMD 1” happy hardcore, but it was the beginning. The darker side of rave music crept in around 1993 – there were moodier breaks and strings, and the uplifting pianos and vocals were disappearing. But suddenly, they all started coming back. Simultaneously, DJs like Ramos, Supreme and MC Marley were making similar moves with their RSR Records. That time was also the beginning of Hectic Records, Seduction’s Impact Records and Slipmatt’s Awesome label. You could hear the formation of what was becoming happy hardcore.

Slipmatt: On one hand, I can proudly say, “Yeah, I started happy hardcore.” But some people will be like, “Oh yeah, Matt started that fucking happy hardcore thing.” I don’t remember who, where or when I first heard the term “happy hardcore”, but I imagine someone, somewhere probably described the new faster, kick-drum-led hardcore as “that happy stuff”. I do remember lots of discussion about what else we could call it, because [happy hardcore] just didn’t sound very cool at all.

DJ Dougal: The turning point for me was when Murray booked me to do the 1AM set at Dreamscape’s 1993 New Year’s Eve rave. I came on and went straight into Sonz of a Loop Da Loop Era’s “Far Out”, followed by every single big, uplifting hardcore tune of the moment.

I’ve still never seen anything like it – the place just blew up. It changed my life overnight. I was still at college, and I’d be sat in my lessons with my Nokia brick and my diary, getting a call every five minutes. I was booked up for a year in advance.

Darren Styles (DJ, producer as one half of Force and Styles): From there, it became a case of if you played that style that Dougal played [at the 1993 NYE Dreamscape], that was happy hardcore. Then the other styles – rather than being called dark – just became known as jungle and drum ‘n’ bass. It was still breakbeat-y, then Slipmatt introduced the kick-drum more to his tunes, and DJ Vibes did the same, as did Dougal. Then we all followed suit.

Grant Smith (Producer, promoter and the Slammin’ Vinyl record label co-founder): Happy hardcore was instantly a term we hated. You’d see magazines like Mixmag refer to it in a very derogatory fashion. Because it was such a significant part of our events, we really took offence. For the mainstream dance media to take the piss like that, I thought, ‘I bet you lot were off your chops doing pills a few years ago. Leave these kids alone.’ The merchandise sales spoke for themselves, though. There was a point when you couldn’t move in many school grounds without seeing a happy hardcore label or promoter-branded bomber jacket. The merch sales often out-sold the records.

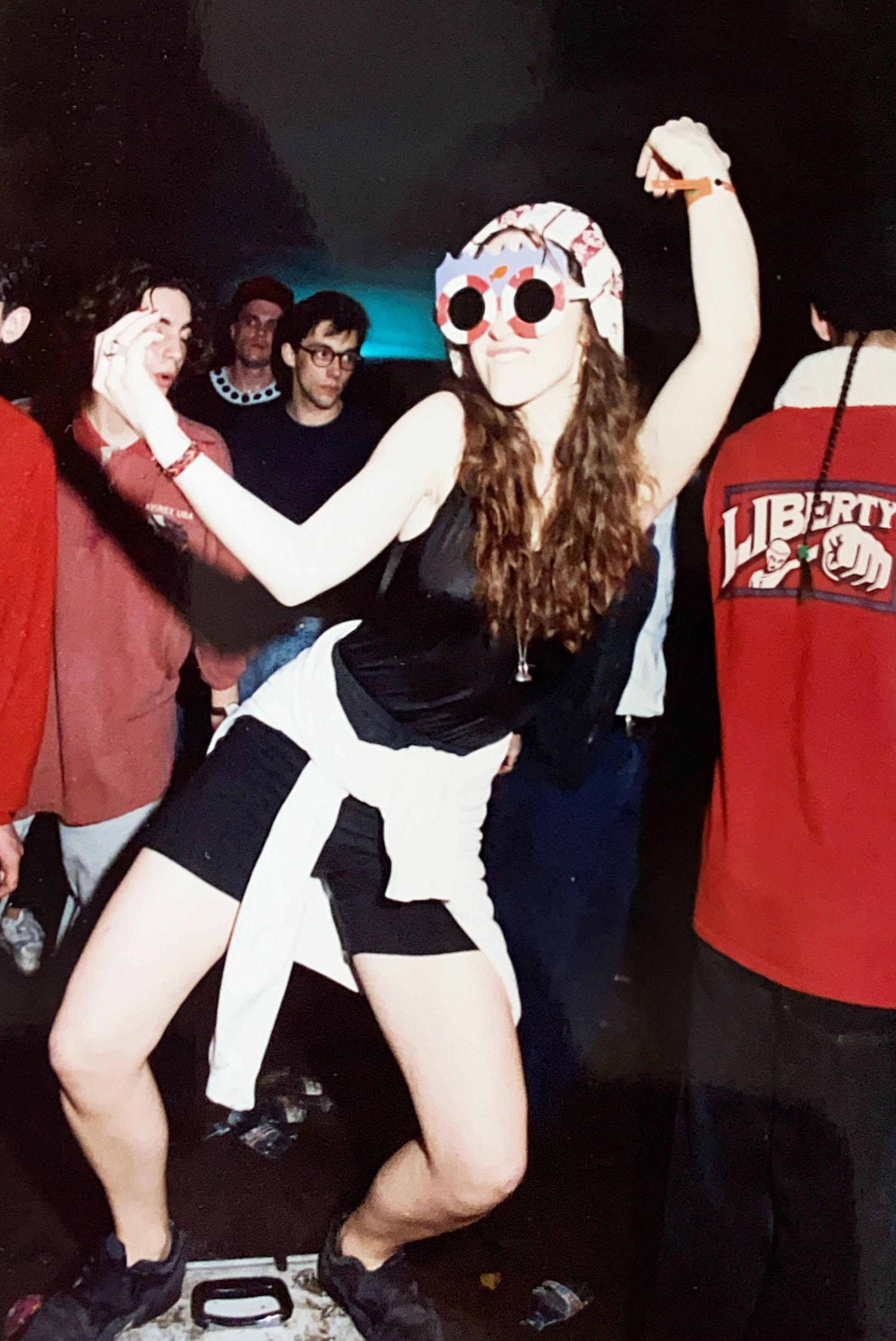

Imran Khan, AKA MC Magika (Birmingham’s leading hardcore MC): When the original hardcore scene fragmented into happy hardcore, that was for me. The crowds were just so ecstatic. They were 100 percent drug-fuelled. The junglists were smoking and drinking. The happy hardcore lot were on chemicals, hard, and that’s the truth. The euphoria was great. I remember a time when white girls wouldn’t look at an Asian guy, then I went to my first rave and every judgment was out the window. No discrimination, all love and happiness. White women were actually talking to me. That whole sense of unity is what I joined.

When I went to jungle events, I noticed the people were changing from the early hardcore days. Once upon a time, smelling ganja was a new thing, then all of a sudden you’re smelling crack. There was a lot of people coming with a bad mindset. I loved jungle music, but hated the audience.

Shane Lavan, AKA DJ Vibes (DJ, producer): The term arrived around early 1994. It was all tinklier pianos, soaring vocals and strings. The tempo came up to 160 BPM. Happy hardcore was taking off. Me and Dougal produced a big track called “Feel Free”. I would call that the epitome of happy hardcore. I know that sounds funny, because it’s my own track, but it was a benchmark. Me and Dougal were the gods of happy hardcore.

MC Charlie B (early hardcore MC, Slipmatt’s partner): I was always 100 percent behind happy hardcore. It was just amazing. You’re always going to get haters, but for me it always will be a great form of music. You can’t beat that vibe at a party. Everyone was there to have a good time and dance. Drugs were obviously integral. It was all about banging Es, which drove the euphoria. I’d say 99 percent of people were off their heads.

1996 – 1998: ‘Why Don’t we all just go bonkers?’

Slipmatt: The further you got out of London, the stompier the music got – they just loved a stompy 4/4 beat. Your bigger cities, like Birmingham and Manchester, were sonically closer to London, so more breakbeat-y. The more north you’d go, the stompier it got. You’d get up to Scotland and they’d want bloody gabber. The same with the south coast – the deeper you go into Cornwall, it’s the same situation. There was definitely a pattern you can track on a map.

Darren Styles: [Force and Styles’] “Heart of Gold” got signed to United Dance, Chris Brown’s label. Chris was DJ Eruption and various other pseudonyms. We came at production from a completely different place to most other producers of the time. All the main guys, like Slipmatt and Vibes, knew all about sampling, but we just couldn’t work out how they did it, so the only way we could get vocals was by finding someone to sing them. It was by default, but ended up working in our favour.

Jenna [Force And Styles’ vocalist] was the year below me at school – she lived literally round the corner. So we banged out a song called “Wonderland”, and soon everyone was playing it. Back then, it was totally acceptable to go to a rave and hear the tune-of-the-moment played by every single DJ on the bill. For a couple of years you’d hear “Heart of Gold” played at least once an hour. Bizarre. You just don’t get that anymore.

Chris Brown (Producer, DJ, promoter and United Dance founder): I fucking hated the happy hardcore tag, and still do. I never had that musical direction as my sole intention, so when the scene started getting such flack within the wider dance community it was really frustrating. I made some really big tunes, and it’s not that I’m ashamed of DJ Eruption hits like “Party Time”, but it’s much easier now to stand back and look at them with distance and recognise the positive influence they had, now there’s not so much stigma attached.

DJ Hixxy: [The DJ Hixxy and MC Sharkey song] “Toytown” was pivotal for us, and for the scene. The day we pressed “Toytown”, I remember Slipmatt, Dougal and Ramos were all there. We played it and literally everyone was instantly, “Can I have that? Can I have that?” It was the biggest reaction I’d even seen a new tune get. A lot of new people seemed to be coming into the scene then, and bought into it as their anthem. Other people said it was the moment they decided the scene wasn’t for them anymore. I’ve listened back to it at points and thought, ‘Bloody hell, whatever was you up to, Ian?’ But I wouldn’t change it. We were living the dream, and that was our mission.

James Horrocks (React label boss): We were always looking for interesting new concepts to turn into compilations. I was also very aware of the cassette tape-pack culture, which was driven by happy hardcore. They were a bit controversial, because lots of DJs didn’t end up getting paid from them, but they probably made as much money as the actual raves. We wanted new artists just breaking through, and Hixxy and Sharkey exactly fit the bill.

DJ Hixxy: React wanted to sign “Toytown”, so we went up to London to meet them. I said, “Listen, forget ‘Toytown’. You can have that, no problem. But I’ve got a bigger idea.” It totally changed the meeting. We sat and discussed [the idea for the happy hardcore compilation albums] “Bonkers” for hours. The name came from a bar in Minehead Butlin’s that we’d played with Ramos and Supreme. I just loved the name.

James Horrocks: “Bonkers” summed up the scene – a mix of computer game samples, scratching and super fast tracks, almost a gabber-style. It just worked, even though [Hixey and Sharkey] really weren’t well-known DJs then. “Toytown” had become a big cult hit, though. It was being used as a terrace chant by Celtic football fans and gaining urban myth-type status. The album took off immediately, and we instantly got the cover of DJ Magazine. It all happened fittingly fast. The second one was Top Ten in March, 1997. The third album included Dougal, and that was the biggest we did. It became one of the best-selling compilations that year. We managed to get into the supermarkets, which was where it snowballed. It was number one in the Woolworths chart, a real high-street album. It sold so well in those stores because the audience was so young and dumbfounded to see something so underground in those kind of spaces.

Jonathan Kneath, AKA Sharkey (DJ, MC, producer, “Bonkers” co-founder): As soon as “Toytown” was released, everything became one big blur of insanity. Sharkey isn’t Jon, it’s a parody act. I’m actually quite quiet, but I had this idea of branding craziness. That’s what raves were all about, right? Losing it. I wanted to put that all into one box and say, “We’re a bunch of nutters from the suburbs that love our beats. Why don’t we all just go bonkers?”

James Horrocks: We knew we were doing well when, amidst our end of year audit, we realised that we were 25 grand up because we’d paid Hixxy a royalty cheque for £25,000 and it’d just sat in his drawer for the best part of the year. The scene wasn’t about money, it was about the music, the energy, the mates, parties and the raving.

If you listened to the radio in the mid-90s, you were waiting for the new Blur or Oasis single. You weren’t waiting for DJ Hixxy. The one exception was John Peel, who was a huge fan. It was very surreal. Everyone was listening to Radio 1 then. Kids would have it on in the evening while they did their homework and their parents watched shit TV. Peel would essentially create us free radio advertisements – he’d announce, “Your ‘Bonkers’ albums are out now, go and pick one up.” We couldn’t believe what we were hearing.

1998 – 2001: ‘Stop the bus, I want to get off…’

MC Magika: I helped launch a new magazine called Dream, and we got invited into BBC Radio 1. It was a huge deal, as hardcore had always been completely shunned by mainstream radio. I sat down with Pete Tong, who was someone I respected very much. He kept going on about how cheesy [happy hardcore] was, and how it just had no body or spirit. It was a lightbulb moment for me, because I realised he was absolutely right.

By this point, a lot producers and DJs had lowered their standards again and again, to a point where they were making music that was just fucking rubbish. There was a new wave of very young kids that were fed this cartoony, ice-cream van, cheeky, cheesy sound, and lapped it up. I respect Hixxy and Sharkey massively, but “Toytown” was a fork in the road. A lot of people absolutely loved that tune, but I think even more people absolutely hated it. You could say it almost destroyed the scene in its current form.

Carl Billsborough, MC Storm (longstanding MC): From late-1997, you could feel the scene hitting turmoil. The energy was being sucked out of the crowds and the attendance was dropping month by month. I was lost in the music, so I couldn’t understand what was going wrong. People left the scene – it was like rats off a sinking ship. Many DJs moved onto drum ‘n’ bass, and lots of MCs left music altogether. Showing up at a half-empty rave was devastating.

Darren Styles: The term developed huge stigma. It really started going downhill in the late-90s – there were a lot of raised eyebrows and it became increasingly uncool. Towards the Millennium, the scene started feeling like a wilderness.

Chris Brown: The term happy hardcore itself created a divide that was never necessary. Around ‘98 the music really started getting stupid. We had a studio in our office at the time and we used to get people coming in and banging out a tune in a few hours. They were fucking terrible. We’d often then sell bucket loads of said tune, though. It got to the point where it just wasn’t what I wanted to do or be tagged with anymore, and I think it was the same for a lot of key players. I was like, “Stop the bus. I want to get off.”

Stacey Beetson: By the time Murray died [in March of 1996], perhaps coincidentally, it started feeling like the end of an era. I think he knew in his heart that Dreamscape couldn’t go on forever, and he was always looking towards the future.

Chris Brown: I was really good friends with Murray Beetson – I was with him on that unfortunate night. It really was horrific. I’m definitely never going to buy a Porsche 911 again. He’d always push boundaries and evolve things. He was came to things in the same way as me. After that, things became pretty slack. I didn’t have anyone to really compete with. That really was a massive loss.

DJ Dougal: Happy hardcore was a bubble, then the bubble burst. It’s the same with any sort of fashion – once everyone’s into it, it’s not cool anymore. The next lot of kids don’t want to be into whatever their big brothers or sisters were into. Around 1997, it was incredible. I was so busy, doing five bookings on a Friday night and five bookings on a Saturday. Hardcore became inescapable. Then garage music came in. At that point, I really did think, ‘Oh God, this could be it.’ It was literally the complete opposite of everything that hardcore was about, in both sound and attitude, and the realisation that this was now what the kids wanted made us question whether we could ever come back from this decline.

DJ Hixxy: We’d built so much stigmatism by ’97, ‘98. The brand got so uncool, I kept questioning, ‘Why has it got this stupid bloody name?’ But when you listened to it, you couldn’t really deny that the music fitted the name. We got so much shit in the press, and because of that most radio stations and even a lot of venues didn’t want to touch us with a barge pole.

MC Storm: The moment that will always stay with me has to be Helter Skelter’s Millennium Jam on New Year’s Eve, 1999. It was £100 a ticket. We got there and it was very disheartening. The numbers were so down. By then, garage was starting to take over. It was turning everyone’s head and gaining lots of commercial success in ways we’d dreamt of. One minute we were in the main arena in 1997, then the next thing we knew, we’re in the bottom room playing to 50 tired ravers.

DJ Dougal: When garage happened, the bookings dropped epically – we’re talking by about 95 percent. We’re all thinking, ‘What the hell do I do now? Should I be making garage?’ Funnily enough, I did have a go at that, and managed to get a few bits on Luck and Neat’s album, so I had a little dabble. But I used that period to explore production in every shape and form.

DJ Hixxy: We’d become the butt of UK dance music’s joke. I just felt gutted that we had so many home-grown talents but couldn’t ever get any radio play. We became the cool thing to bag upon.

2002 – 2012: ‘If we’ve got to move a mountain, then we’ll move two’

DJ Dougal: Happy hardcore had gotten stuck. We couldn’t move it forward. Towards the Millennium, at the same time UK garage was taking over clubs and charts, the other sound on the rise was trance. You had artists like Ferry Corsten coming through with these array of new synthesisers – the Korg M-1 keyboard, and then this crazy new keyboard called the Virus. It had this incredible sound you can still hear all over tracks today. We all thought it was incredible, and started integrating it into our hardcore. Darren Styles was one of the leaders. He took the kick-drums they were using in trance and adapted it with amazing new power and drive. The brand name “happy hardcore” had such stigma by then that the only way a new version of it stood any chance of being accepted was by re-branding it, so “UK hardcore” was born.

MC Storm: In the year 2000, at the real lowest point, Slammin’ Vinyl organised a crisis meeting in London. Everybody was there. At that meeting, people talked about the music, about the promotions, about how we were presented in the media, about the stigma and about what the future could hold. The conclusion was: let’s all work together, pull up our socks. We’ll do whatever it takes to get this ship back in the ocean. If we’ve got to move a mountain, then we’ll move two.

Darren Styles: Forcey was five years older than me. He had a kid and a life, but hardcore was still all I thought about. I had no other responsibilities. I wasn’t ready to give up. There was this whole new world of sounds arriving from trance that really resonated with my tastes. I thought to myself, ‘Is this the new direction we’ve all been searching for?’ Then it started to kick off again, and this time went up to a whole new level.

Joseph McHugh, AKA Joey Riot (Scottish DJ and producer): I got made redundant in 2002. I’d just turned 26, and started thinking, ‘If I don’t have a crack at music soon, then when am I going to?’ In Scotland, hardcore was always driven by the bouncy techno sound, rather than English happy hardcore, which you can hear in pioneering producers like Scott Brown. I wasn’t even making hardcore at the time, I was making trance. I was also MC’ing at the time, and got booked to MC an event in Leeds that had Breeze, Scott Brown and Darren Styles playing, and I heard what was then becoming the new inception of trancey hardcore, or trance-core. It perfectly fit my tastes and history. I made one track, called “Saving Grace”, and through a friend got it to DJ Sy, who played it that weekend at [the club night] Hardcore Heaven. That was it: I went from being a failed trance artist to a hardcore producer in the space of a week.

DJ Hixxy: If you look at most revolutions or evolutions in electronic music, there tends to be a development in technology at the root of it, and that was definitely the case when trance hit. It was all uncharted territory and felt so fresh – exactly what we needed.

Matthew Lee, AKA Gammer (DJ, producer, and enduring happy hardcore brand ambassador): My mum was Dougal’s ironing lady. When I found that out, it blew my mind, because I’d been obsessively listening to his Bonkers 7 CD for over a year. I was star-struck. She got him to let me visit his studio, and his engineer gave me a cracked copy of Reason. Then, one day, I’m in my bedroom after sitting up all night playing Counter-Strike in the pitch back with the curtains drawn. I’m 13 years old, with a bizarre bum-fluff beard. The door opens and DJ Dougal is standing there. He recalls it like walking into a troll’s cave, like he was in danger.

I came downstairs and he was like, “I heard some of the tunes you made, they’re really cool, we should work on something together.” Next thing I know, I’m making music with DJ Dougal, then I’m in a mastering house watching our tune get mastered. I’m pinching myself, but going with it. One day he gives me this CDR and says, “This is the sound that’s about to kick off.” It was a CD with a bunch of songs from a duo called Breeze and Styles. They were all really trancey, as trance had suddenly entered hardcore. It immediately grabbed me.

MC Storm: Hixxy called me to ask if I would be a part of a new label he was starting, called Raver Baby. I didn’t even have to think about it, I just said yes. Almost everyone that was driving this new sound was on board. There was a new sense of unity. We were all on this new team and wanted the same thing. Suddenly, there was a raft of new tracks from Breeze and Styles, Hixxy and UFO, and by then Scott Brown was churning tunes out left, right and centre. I get goosebumps just thinking about that time.

Before long, the incredible Twista Records crew arrived, with Recon and the late, great Squad-E. There was resistance from the older ravers to the trance-driven sound, but it didn’t matter, because the new class didn’t give a shit about the past, which was energising. Slammin’ Vinyl were booking bigger and bigger venues again, and selling them out. Then, in 2004, Hixxy evolved Raver Baby with the Hardcore Till I Die events. You had that on a Friday and then Hardcore Heaven on the Saturday. Over a weekend, we’d have over 7,000 people out. Hardcore was back.

Grant Smith: There wasn’t ever a point where we gave up on the scene. The happy hardcore noughties rebirth was maybe as strong as its 90s peak. It felt less cheesy and had more energy to it. I wasn’t personally a huge trance fan, but it gave UK hardcore a new lease of life. In 2005, we did a show at the NEC in Birmingham. The main arena that night was hardcore, so we’re talking over 5,000 people in one room. That was another genuine peak for the movement.

MC Storm: The 2000s built and built. Hardcore’s commercial struggle has underpinned its history. “Bonkers” broke ground and hit new commercial heights, but then disintegrated. Darren [Styles] and Ian [Hixxy] had a meeting with All Around The World, the label behind the massively popular Clubland album series,. The result was the Clubland X-Treme Hardcore compilations. I’m lucky enough to now have gold discs on my wall from Clubland. Darren was the main act on the Clubland tours, and he took me and MC Whizzkid out with him. It was phenomenal, another massive turning point for hardcore. Darren did it in 1996 with the “Heart of Gold” era, then he did it again in 2004 with the trance era. He’s done it twice for our scene. I just hope that little fucker does it again.

2012 – 2021: Power-stomp, dub-core and, erm, HDM

Gammer: I distinctly remember the first time I heard [Skrillex’s] “Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites” – I’d literally never heard anything like it. It was incredible. You put on one of our songs from that time next to a Skrillex song and it was a no brainer. I’ve got no qualms about saying that. I discovered bass music and then I discovered trap, TNGHT and Hudson Mohawke. Between me, Darren Styles and Breeze, we all thought, ‘Well, once upon a time we made hardcore sound like trance, and that worked. What if we make hardcore sound like dubstep? That’ll work.’ Unfortunately, it just wasn’t very good at all. Not only was it not very good, but it didn’t work at raves.

MC Storm: I didn’t understand the dub-core stuff. I didn’t like it and I didn’t understand it. The dancefloor didn’t like it or understand it either.

Gammer: Joey Riot and DJ Kurt came out with their new take and re-branded it as “power-stomp”. The timing was beautiful. It was partly an homage to the old bouncy techno that was big in Scotland, but I genuinely believe that had “dub-core” not been around, power-stomp would never have taken off. The reason it worked so well is that it was seen as the saviour. They say, “Die a hero or live long enough to become the villain.” Well, we’d become the villains with this bloody dub-core thing. Then Joey comes in to save the day with power-stomp.

Joey Riot: I couldn’t figure out a new direction, then ended up going to a few of the Sensation Black events in Holland and really fell in love with the hard-style sound. I went to the Amsterdam Arena, the bloody football stadium, with 60,000 people all raving to hard-style, and was like, ‘What the fuck is this?’ We had to bring it back to the UK. At first, me and Kurt literally just tried speeding up those European hard-style tunes, just pitching them up. I remember dropping a few at West Fest and literally clearing the entire dancefloor. Eventually we ended up combining the reverse-bass sounds of hard-style with the pulse of old-school bouncy techno, and it swiftly started getting traction. We floated the “power-stomp” name online and people just jumped on it. Within a year, it was massive.

Gammer: If Joey Riot doesn’t want to be known as happy hardcore, that’s absolutely fine. But Joey is someone who’s always done his own thing. When he and DJ Kurt came into the scene, I think, if we’re honest, we all saw them as a threat. I’ve never said this publicly, or even talked about it to anyone other than loved ones, but that’s the reality. My rise in hardcore just happened to be at exactly the same time as the Hardcore Awards started, so I ended up winning so many in a row it weirdly began to feel like it somehow defined me. But by the time the Hardcore Awards finished, I wasn’t trying to be the best DJ or producer for any of the right reasons. I ended up pushing myself into oblivion just because I didn’t want Joey and Kurt to take it from me. Because if I’m not the best hardcore DJ, then who am I?

I’ll try not to turn this into too much of a therapy session, but being hardcore and being the best was all I had. I was caught up in this really horrible rat race in the end, and it was exhausting. The sixth and final year of the Hardcore Awards was when the actual award went from being a big trophy to being a printed out piece of paper in an A4 frame. It was also the year I was being bullied and picked on by what felt like most of the UK hardcore scene. I remember standing onstage, thinking, ‘What is the point?’ I was so unhappy. Joey was the black sheep and I was so threatened by that. But I have nothing but respect and admiration for him to this day. He does what he believes in. It got my back up, because in my heart I knew that was exactly how I wanted to be.

Darren Styles: By around 2007-ish, we hit another crossroads. In the early noughties there was much less to choose from – drum ‘n’ bass, UK hardcore and hard house. Towards the end of the decade, with the arrival of EDM, the choices within dance music blew nuclear. The music that UK hardcore producers were coming out with had also probably seen better days. But weirdly, the moment of the noughties UK decline was timed exactly with the rise of EDM, which was finding huge new audiences across the world. When we were at our most popular in the UK, I was probably only abroad a few times a year. Then, as the UK scene started to go downhill again, I found myself in America, Australia, Holland, France every other week. We began to make a conscious decision to focus on the Electric Daisy Carnivals and that sphere of bigger international events.

Gammer: When Calvin Harris made a song with Rihanna, that was a big fucking deal. Suddenly, the term EDM is born, and by definition encompasses all electronic dance music. Suddenly, big festivals are happening everywhere and dance music exists in the States, which – I really cannot stress hard enough – was never the case before. All this stuff happening at once, but hardcore had nothing to do with any of it. As tragic as it sounds, most UK hardcore DJs were just left behind, squabbling amongst ourselves over the crumbs back home. I think a lot of it was desperation, trying to win back those 90s glory days.

MC Storm: Recent years have been a challenging time. At times, a little bit heartbreaking. But hardcore definitely has a future. It’s loved by hundreds of thousands of people in this country, and millions around the world. So it’s not going anywhere as a sound. I just want raving to last forever. It’s given me so much – more than I ever could explain. So if it can give that to other people, that’s very cool.

Gammer: [American producer] Porter Robinson released his album Water, and I loved it. I tweeted him, “Hey, I love ‘Sad Machine’. Can I do a happy hardcore remix? Lol.’ He immediately sent me the stems. I rang Darren Styles and said, “Shall we do it together?” It blew up, interestingly more in the States than it did over here. Next thing you know, we’re being asked to play Wonderland, one of the big US festivals. So me and Darren, UK hardcore DJs, are closing out the hard-style stage at a big US festival. It felt like the early days again. All these kids didn’t judge it, they just danced.

Darren Styles: If someone asks me what kind of music I make now, I just say it’s some form of hard dance. To me, that’s what it is. If someone else calls it happy hardcore, that’s fine with me, but I personally don’t see it as that. I count happy hardcore as the Force and Styles era, what Billy Bunter was making in the 90s, what Slipmatt was making, squeaky vocals and all that fun stuff. Not what the music has become now. For me, hardcore is on the up again. Just before lockdown, every time I put a gig on sale it would sell out. I’d managed to have some bigger, relevant tunes out again, my profile got bigger around the rest of the world and suddenly the UK felt ready for it again.

Gammer: When we put the Porter Robinson remix out, I consciously went back to using the term happy hardcore. It felt like everybody had been constantly bickering about what to call the music since the dawn of time. When EDM conquered the planet, it was impossible to ignore, so people within the hardcore scene started talking about re-branding it as HDM? As in, hard dance music. I thought, ‘This is fucking stupid.’ I was also playing loads in America and Australia, and I realised that not only do they still call it happy hardcore out there, but there was a lightness to it. They’d say, “Oh man, I love it when you play happy hardcore.” These festivals, we’re talking face painting, flowers, candy kids and all that good stuff. Not three kids in baseball caps saying, “I’m literally gonna kick you in the teeth if you play a dub-core track.” Which, yes, did actually happen.

Joey Riot: If you look at the cyclical nature of dance music, I’m very confident about the future of hardcore. I don’t think the music has ever been this good. When you go to places like Australia and play at these huge events where hard-style and these huge global phenomenons are so popular, you can drop UK hardcore tracks and they go off. It proves a point that what we do here can stand up anywhere in the world. It may not come back as a national scene in the same way that it has done in the past, but I don’t care.

That was actually quite limiting, because we didn’t ever work with people outside of our wheelhouse. But now people like myself, Hixxy, Gammer and Styles are all trying to be a part of this global harder EDM market, and the music we’re writing has a place within that. I’ve never been so excited about music, which is weird, because I was close to quitting a year ago. I was so jaded with touring, but right now I feel like I did when I was just first starting to breakthrough in hardcore.

Gammer: I would categorically declare that I’m not part of the UK hardcore scene now. Neither do I want to be. I still love the music, but I’m happy to just do my own thing. Hand on heart, I owe everything to it. I’m very happy with my time in the scene. But life is a lot simpler when you don’t worry about what other people think. I always now make the point of grabbing the mic and screaming, “Who’s ready for some happy hardcore?” When I do, everybody cheers. This is why I say it’s important to separate the music from the scene. The music is still alive.

I know what happy hardcore is. When I’m up onstage, playing a happy hardcore remix of “Let It Go” from Frozen, I know exactly what it’s about. When I’m onstage at Excision and I’ve heard 6,000 dubstep records with absolutely no breakdowns back to back, and then I come on and play Frozen and everyone’s got their hands in the air, I know what it’s all about. It’s corny and it doesn’t give a fuck – and is that not what raving is supposed to be all about?