Patricia Yang had an agreement with the other Georgia Institute of Technology grad students using the lab space she was assigned: She and her collaborators would only work after 5 pm. That’s because, come work time, Yang unloaded several buckets of animal feces from a refrigerator. “The smell was incredibly bad,” Yang reports.

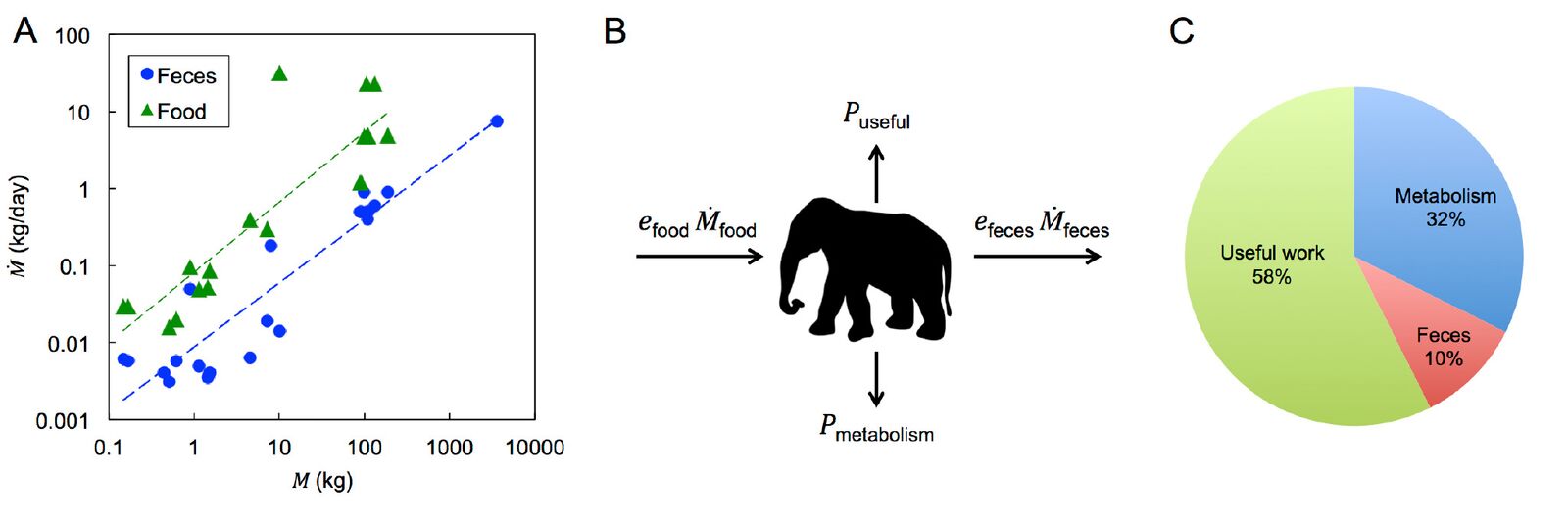

Yang is earning a doctorate in mechanical engineering, but so far her work has examined the interworking of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems of animals as if they were carburetors or fuel cells. In her first paper, she and coauthors demonstrated that the size of an animal species does not affect the duration of time it spends urinating. In a fitting sequel, entitled “Hydrodynamics of Defecation,” she lead a team trying to determine why mammals, despite the great variances in the size of their bodies and their size of their shits, spend about the same amount of time taking a shit. The study was recently published in Soft Matter, a journal dedicated to liquids, polymers, foams, gels and similar things.

Feces does move through the rectums of different creatures at different speeds, from the six centimeter worth of poop per second of an elephant to the one centimeter per second of a cat, said Yang. However, most healthy mammals continuous defecate for somewhere between five and 19 seconds. The time spent dropping dookies seems not to be in ratio to creatures’ size, which varies immensely across the animal kingdom. Humans, she added, expel more than one digested stool sample at once, which could be a reason—issues like constipation aside—why many of us spend more time on the toilet.

Yang and her coauthors concluded that the larger the animal, the more mucus its large intestine produces to quickly and efficiently shoot out its waste products, “similar to a sled sliding through a chute,” the study states. “Larger animals have not only more feces but also thicker mucus layers, which facilitate their ejection.” Yang, the lead author, teamed up with two biology students, her academic advisor, and a consulting medical doctor, who all have their names on the paper. As for their research methods? Imagine the creators of South Park got to do a National Geographic special.

In order to document just how much time various mammals spend on a bowel movement, Yang and her compatriots got permission from Zoo Atlanta to film their animals. They chose elephants, warthogs and giant pandas. These species were picked for a number of reasons: Their sizes varied greatly. All produced what Yang calls “cylindrical feces,” as opposed to pellets or goo, eliminating shape and consistency as a variable. Lastly, these creatures are “not shy,” says Yang. All drop their deuces in the open, allowing for easy filming.

Videos by VICE

Georgia Institute of Technology

The team added a forth animal: common dogs. Again using digital cameras, they compiled that data at a local park. In addition to their own footage, they utilized YouTube videos of these four species completing a number two—of which there are surprisingly many, said Yang. The point is they got a good measurement of how long these animals typically pooped. They also took stool samples back to Georgia Tech to examine them for normality and mucus consistency, perhaps becoming the least popular researchers in their building.

The resulting paper is 27 pages, contains some creative analogies (“Like a tugboat pushing a barge, rectal pressure pushes feces through the large intestine”), and a mathematical model of defecation. Snicker if you’d like, but Yang notes that many diseases are understood through examining feces and understanding what is and isn’t normal. “Surprisingly, not a lot of people have approached this from a physics perspective,” she adds. She says she has discussed her work on first dates.

“Usually, I will make sure it’s not dinner or lunch. I usually say I study food. Then I look at their reaction from sentence to sentence to see if I should go on.”

Read This Next: Let’s Be Real, Americans Are Walking Around With Dirty Anuses