This story appears in the September Issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.

Long before President Donald Trump coined the term “fake news,” disparaged the New York Times, the Washington Post, and CNN, or declared a war on the media, there was a dogged reporter named Ben Bagdikian, who rattled the Nixon White House and landed on FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s enemies list.

Videos by VICE

Bagdikian, who died in March 2016 at the age of 96, was the dean of the journalism school at the University of California, Berkeley, and an Armenian American journalist and author who was probably best known as the reporter who obtained a copy of the Pentagon Papers about America’s secret role in the Vietnam War—the greatest and most important leak in US history—and advocated publishing it in the Washington Post to his editor, Ben Bradlee.

After his death, I filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the FBI to see if the bureau had any documents on Bagdikian, given his place in history. Sure enough, a year later the bureau sent me its file on the muckraker: nearly 200 pages, spanning more than two decades.

The FBI first opened a file on Bagdikian in 1951, digging for dirt on him simply because his reporting pissed them off. More than half a century later, the Trump administration has threatened to do the same thing to journalists who dare write critically of the president and his family. The files underscore that as Trump openly battles with the Fourth Estate, the venom he spews, while alarming, is not unique.

What initially set off Hoover and the FBI was a series of stories Bagdikian published in the Washington Star titled “What Price Security” that was about—wait for it—Russia and communist sympathizers. Specifically, Bagdikian condemned a government program to issue “loyalty checks” to employees in order to ensure “hostile agents and unreliable citizens” were not infiltrating it.

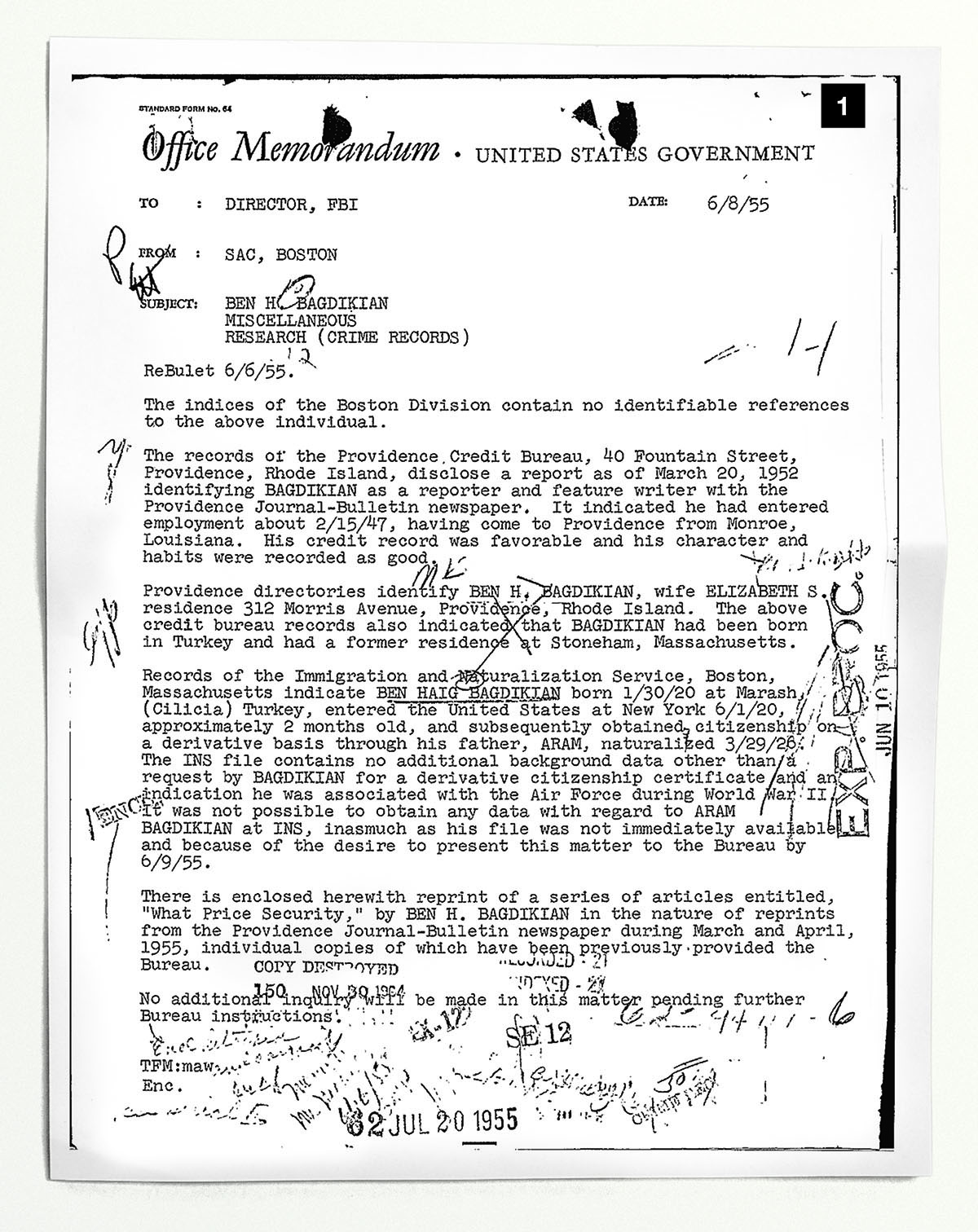

1. After Bagdikian’s series was published, an FBI Special Agent in Charge (SAC) from the Boston field office (Bagdikian was a former Massachusetts resident) sent a memo to “Director, FBI” (Hoover), informing him about the status of a criminal search for records on Bagdikian. The term “ReBulet” on this page means “Referring to previous Bureau Letter.” The memo notes that the FBI’s Boston office did not have any records on Bagdikian, so the FBI went a step further and looked up Bagdikian’s credit report, which is illegal without a warrant. The agent noted that Bagdikian’s “credit record was favorable and his character and habits were recorded as good.”

2. There’s a saying that goes, “If you are pissing people off, you know you are doing something right.” This May 23, 1961, letter to “Mr. DeLoach” (Cartha DeLoach, who went on to become Hoover’s top aide and the FBI’s liaison to the White House) from FBI agent D.C. Morrell, is evidence Bagdikian was doing something right. Apparently, the bureau was not happy with Bagdikian’s article in the Providence Journal-Bulletin marking Hoover’s 37th anniversary running the agency. Morrell noted that Bagdikian’s story “made a number of snide comments relative to the FBI and to Mr. Hoover.” Hoover’s response? “See that Bagdikian is not on our mailing lists and gets no cooperation.” (I doubt Bagdikian depended upon access for his reporting.) The memo then highlights the FBI’s troubled relationship with the Journal-Bulletin due to “vicious” editorials that took the FBI to task for being, in Agent Morrell’s words, “almost immune to the traditional process of checks and balances,” notably regarding its confidential informant program. The memo has some parallels to news stories that were published about the agency in the last ten years.

3. On July 20, 1967, DeLoach sent a letter to Mildred Stegall, one of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s closest aides. Apparently, she’d requested an FBI records check on Bagdikian and the editor of the Riverside Press-Enterprise in California. By this time, Bagdikian was a contributor to the Saturday Evening Post. It’s unclear from the documents why Stegall wanted background information on Bagdikian, but DeLoach informed her the FBI had nothing derogatory. He did, however, alert her to the series of articles Bagdikian had published 12 years prior, “which were critical of several phases of loyalty investigations concerning government employees.”

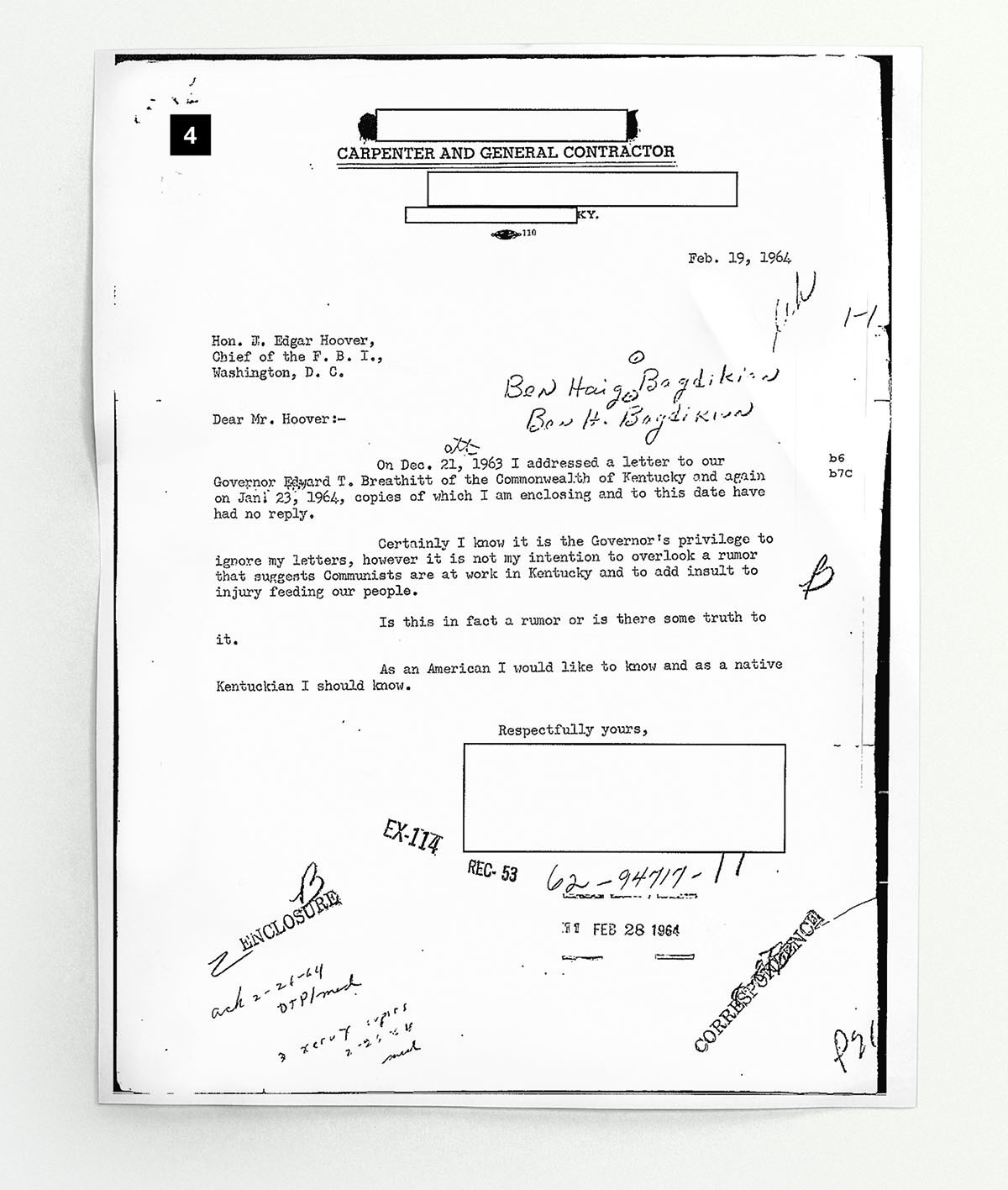

4. It wasn’t just the government that was alarmed by Bagdikian’s reporting; his readers were, too. In fact, in 1964, one reader from Kentucky wrote a letter to Hoover after Bagdikian reported that communists were feeding hungry citizens in his state. “It is not my intention to overlook a rumor that suggests Communists are at work in Kentucky and to add insult to injury feeding our people.”

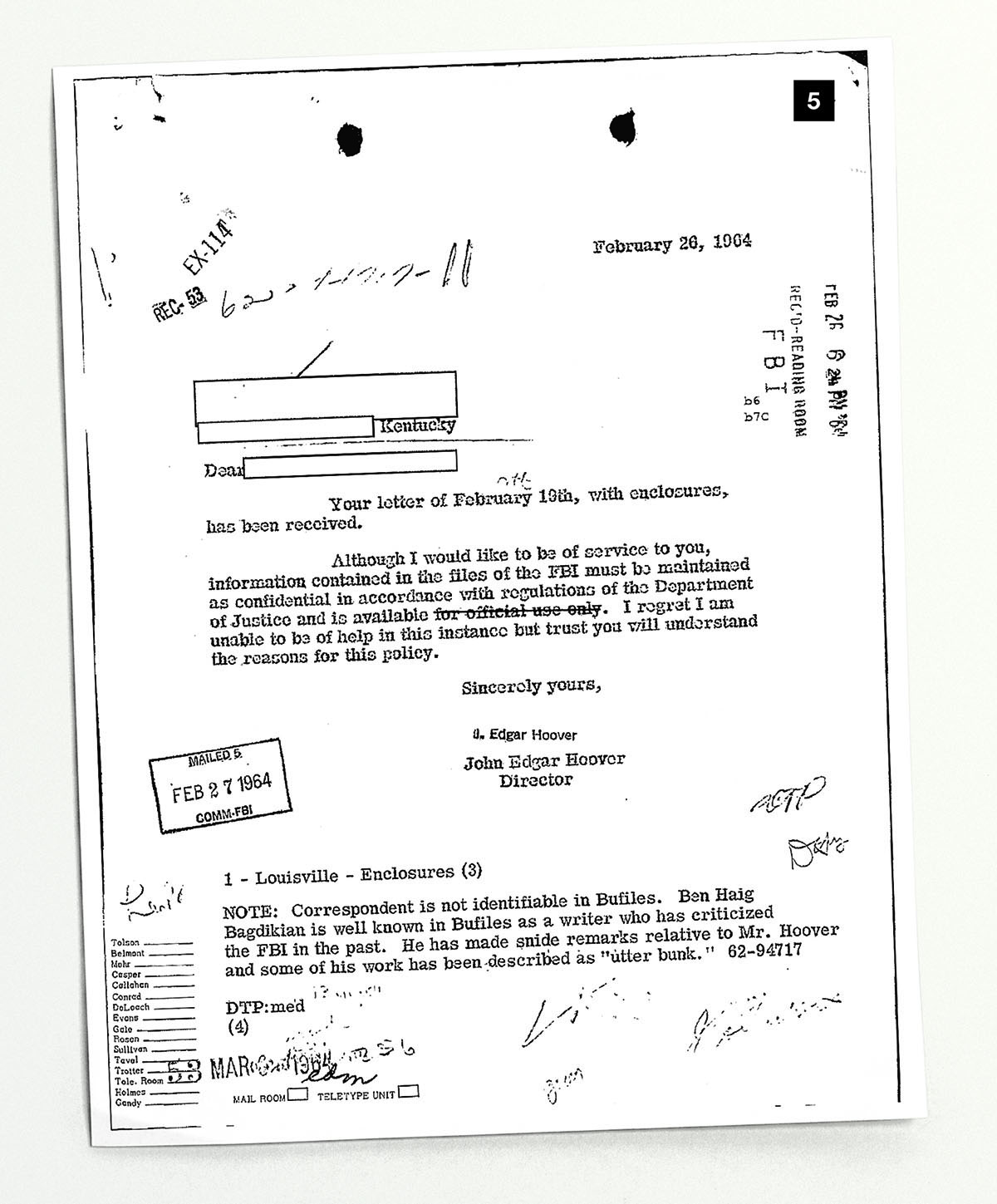

5. Hoover personally responded to the author of the letter, whose name was withheld, stating, “Although I would like to be of service to you, information contained in the files of the FBI must be maintained as confidential in accordance with regulations of the Department of Justice and is available for official use only.” A footnote to the letter that was for internal use only says, “Correspondent [the reader] is not identifiable in Bufiles [bureau files].” That means the FBI checked to see if there were any records on the reader. The footnote further states, “Ben Haig Bagdikian is well known in Bufiles as a writer who has criticized the FBI in the past. He has made snide remarks relative to Mr. Hoover and some of his work has been described [specifically, by Hoover] as ‘utter bunk.’” (“Fake news” in today’s parlance.)

The FBI began investigating Ben Bagdikian, above, in 1951. Photo via Getty Images

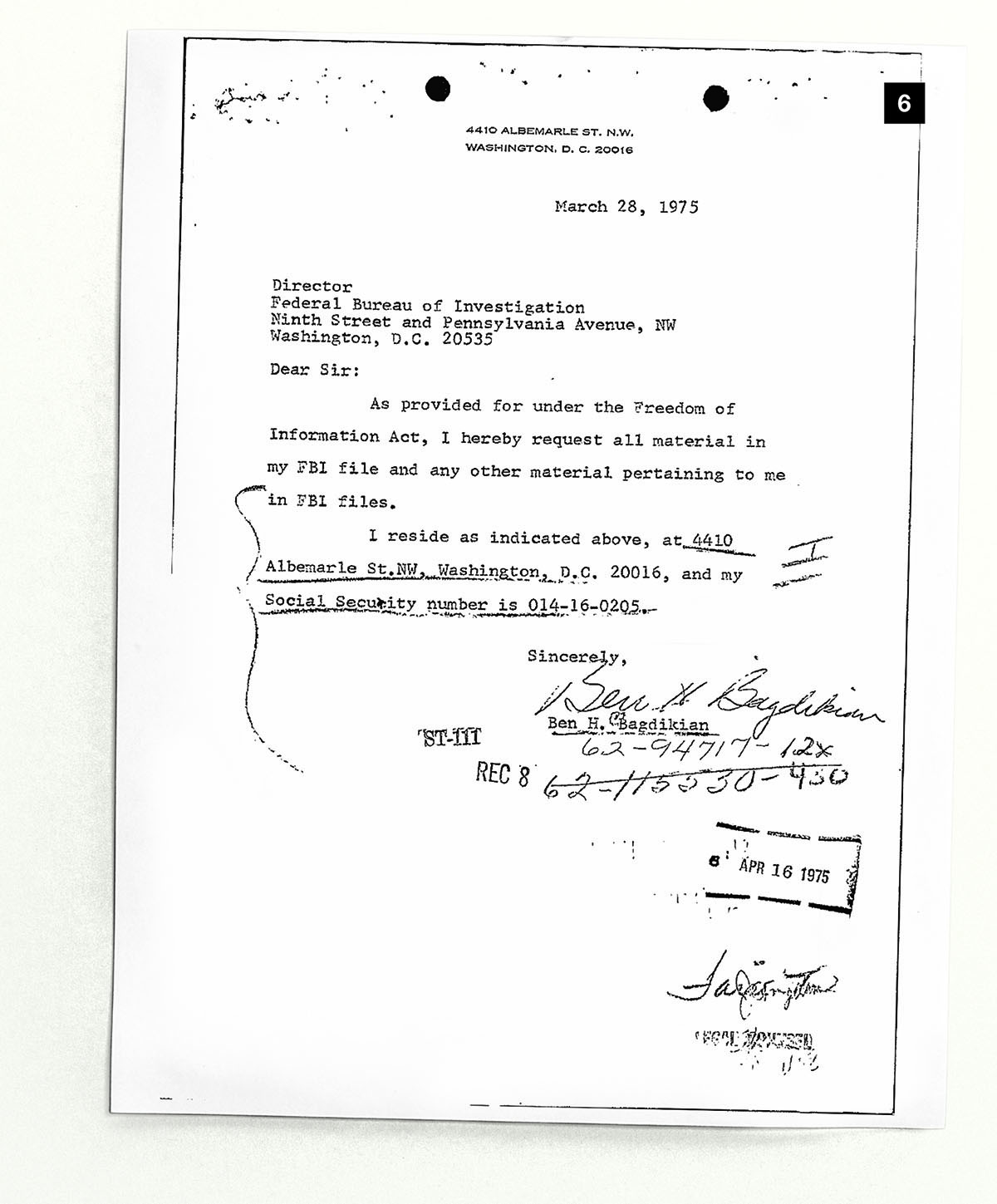

6. Bagdikian must have been well aware that he had been a thorn in the FBI’s side. In 1975, he filed a FOIA request for all records on himself and sent the letter directly to Hoover. The bureau delayed for almost a year but eventually turned over documents, though it’s unknown whether or not it was the full file.

Curiously, the documents in Bagdikian’s FBI file that I received don’t reference his work on the Pentagon Papers, except for an October 12, 1971, memo submitted to his FBI file along with a copy of an article Bagdikian wrote for a special issue of the Columbia Journalism Review titled, “The First Amendment on Trial—After the Pentagon Papers.” The title of Bagdikian’s story was, “What Did We Learn.”

More

From VICE

-

Paul McConnell/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Robin Entertainment