This article originally appeared on VICE Italy.

Inspired by the Beat Generation, Italy’s most famous commune was established between 1970 and 1971 in the town of Ovada, in the country’s Piedmont region.

Videos by VICE

While it might be the most notorious, Ovada wasn’t unique – a lesser-known commune sprung up in 1968, smack bang in the middle of Milan. That group’s founder was Dinni Cesoni, self-proclaimed “commune member and Indian by adoption”.

I spoke to Cesoni, now a psychologist, about the dreams and ideals that went into creating his urban experiment – and how, by 1977, it all fell apart.

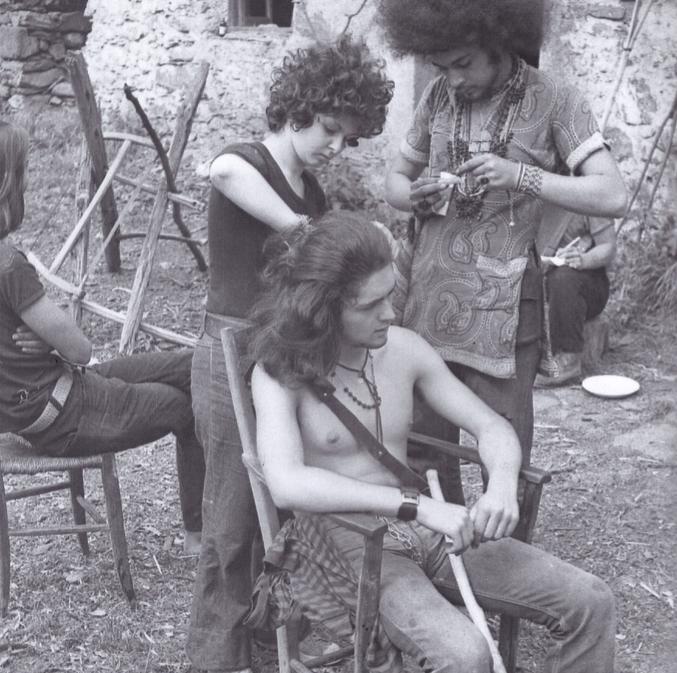

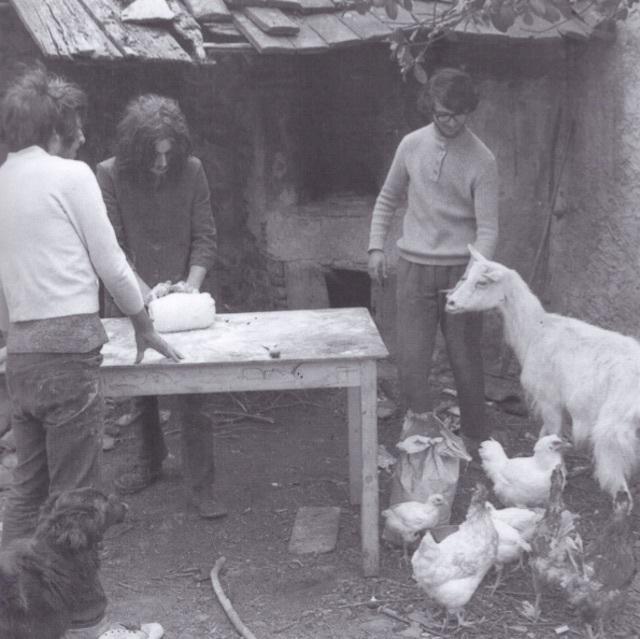

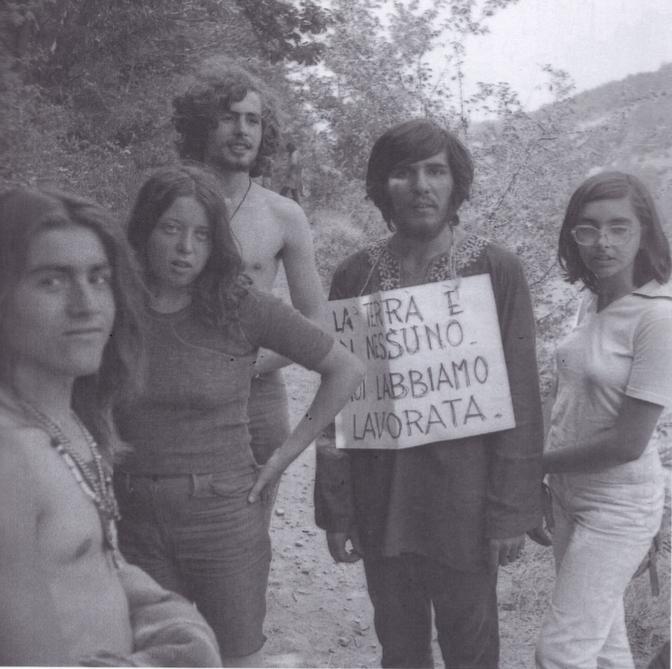

Unfortunately, no photos exist of Cesoni’s commune, but this interview is paired with images from Ovada – taken from the book The Ovada Hippy Commune – Living in Utopia, by Ignazio Maria Gallino – which paint a picture of Italian hippy life in the 1970s: shared work, constant togetherness, free love and lots and lots of drugs.

VICE: Hi, Dinni. Why did you decide to start a commune?

Dinni Cesoni: Honestly, it was spontaneous. At the end of the 1960s, young people felt suffocated by the atmosphere of authoritarianism, and conformity to polite society in Italy. For example, at the University of Milan, us girls couldn’t wear pants – it was totally forbidden. Even though my dad was liberal, the latest I could get home, aged 20, was 8PM.

Around this time, the newspapers started talking about the “Beat Generation” and “dirty hippies”. It was in this spirit of rebellion that I joined the first yoga classes with some friends from high school and university. We knew of communes in Berlin and England that followed the American example. That’s how we came up with the idea. So, six of us – three men and three women, including two couples – moved to Via Vico [in Milan] in October of 1968.

How did you find the apartment? And how did you support yourselves?We were all young, penniless students. We were helped by a 25-year-old architect friend who worked in Milan and knew the city much better than us. At the time, there were these huge fancy apartments that were falling apart, which nobody wanted. We found this crazy place with four bedrooms, a kitchen and what we called the “party room”.

The architect initially contributed his salary, but little by little we all found odd jobs. Some handcrafted jewellery we’d sell at the club at night, another friend started working as a photographer. I don’t know how, but I landed a job as a fashion journalist. Then, another apartment on the same floor became available, and suddenly there were 11 of us.

What was a typical day like?

Let’s just say we never got bored [laughs]. In 1969, many young, working-class people ran away from home and came to our neighbourhood, Brera, which was filled with artists and alternatives, before becoming the boring place it is today. We hosted all the brothers and sisters who passed by for a few days or months, even if they only had a guitar and a sleeping bag. There were never just 11 of us.

We didn’t care about food, we spent hours talking about books – Siddhartha, On the Road, Howl. Only a few of us had read them, but we all knew about them. Oral culture was fundamental to the movement. We were also engaged in the community. Besides writing about fashion, I collaborated with alternative magazines, covering and organising protests.

Have you ever met anyone who lived in Ovada?

Of course – many of our brothers and sisters came from or were going there. It was an important point of reference for the whole movement. They created a utopia before the police cleared them out. People were returning to their roots, cultivating the land, becoming friends with the farmers and swimming naked. They have lots of photos. We don’t – we never even thought about it.

Did your commune practice free love?

Whenever someone asks me about this, they immediately think about orgies. We were actually all very timid. We came from a culture afraid of sex. We were young, we wanted to know what sexuality was, because no one had ever actually explained it to us. Usually, if you were walking across the commune and something clicked, you might end up making love. Mind you, we didn’t have sex – we were all horrified by that word. The physical act didn’t interest us, we were looking for the emotional connection. That’s why many of us, myself included, left for India to study tantra.

Was there any jealousy?

One of the pillars of the movement was saying “no” to jealousy – we viewed it as contrary to freedom. But jealousy is a common human emotion, so it wasn’t always easy to avoid it. For example, we had two couples who broke up and then swapped partners. We all talked about it together, to see if other ideas, like freedom and creativity, could help them understand how emotions towards someone can change. But in the end, one couple couldn’t do it and left the commune.

Did you do a lot of drugs?

We started smoking weed in 1968. To be honest, we weren’t potheads, but when the opportunity presented itself it was a great moment of sharing. It became more common later on. Then, we discovered LSD.

And how was it?

Crazy! The first time I really heard of it and saw its effects was when I joined a hippy gathering in Amsterdam with a few members. When we came back, we talked about it in the commune and decided to all take it together. It was a unique experience, I can’t even describe it. Of course, two of us remained sober as guides. Eventually I stopped, because a few people started having bad trips.

How did it all end?

There were many factors. One was heroin, which is why I’ve worked with drug addicts for 30 years. Unfortunately, some people’s political commitment turned to extremism – for example, many joined the Movement of 1977 [a left-wing movement that organised violent protests] and the Red Brigades [a far-left armed organisation and guerrilla group].

Plus, some people just started a family, others went to India – in short, we grew up. When I look back, it feels like another life, and I’m proud of us. Maybe, one day, young people will continue what we started. But as we used to say in the old commune, the real reason it fell apart was because no one ever wanted to do the dishes.