The year is 1968. The place, Brazil. The military took over the government almost four years ago, and for the past few months, its dictatorial repression has been getting stronger. Meetings of over three people in public spaces are considered to be potentially political and therefore, suspicious. Many cities have a curfew in place. People are regularly arrested for displaying “subversive tendencies” with no further explanation offered. Any piece of music, writing, film, or theatre has to be run past a censor prior to release.

You open a newspaper at a random page and, spread between three pieces of relatively mundane news and a poem, there are four cake recipes—which seems a little excessive. Two of them are exactly the same. One of them ends abruptly, mid-instruction. Another asks for 1 kilogram of salt.

Videos by VICE

Something’s off. Or at least, that’s what the staff of mainstream Brazilian newspapers undergoing severe censorship would like you to think—which is why news deemed unfit for publishing by the government had been replaced by excerpts of “The Lusiad,” a Portuguese poem from the 1500s, and inedible cornmeal flour cake recipes.

“There were people in the newsroom thinking, ‘We need to tell readers we are being censored.’ That’s when the recipes started showing up, as well as excerpts from poems, all being used to convey: information was here, and it was censored,” explains Maurice Politi, head of the Brazilian organisation Núcleo de Preservação da Memória Política [Centre for the Preservation of Political Memory] and ex-political prisoner.

“It wasn’t just political news [that were censored] either,” he continues. “In 1972, there was a meningitis epidemic in Brazil. Over 3,000 children died because it was forbidden to publish in the newspapers that Brazil was dealing with meningitis.”

Today, nearly 34 years since the official end of Brazil’s military dictatorship, the legacy of cake recipes as indicators of suppressed information remains, floating in the ether of Brazilian culture. Time and time again, a random recipe crops up somewhere it’s not meant to be—a way for journalists, politicians, and artists to make reference to the painful times of repression, and inform the public that although not in the same scale, censorship is still very much possible.

During the dictatorship, every newspaper at the time found its own way of resisting the presence of censors in the newsroom. Be it through publishing images of devils, headline-less front pages, passing easily destroyed notes to colleagues, or even humming Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers In The Night” in order to alert the arrival of an unfamiliar visitor among the reporters.

The newspaper O Estado de São Paulo alone was stopped from publishing over 1,100 (known) articles during the dictatorial period, running the same Portuguese poem excerpt 655 times. Many of these attempted to report the suspicious deaths of prominent journalists and activists, as well as political misdemeanours and torture. This number also does not include pieces left unwritten due to self-censorship by reporters, a very prevalent practice at the time for matters of safety.

“We knew when something was censored. Being a journalist at that time was very difficult,” explains Adélia Borges, a journalist who started working at Estado de São Paulo in 1972, at the age of 21. “Not just for being press—any group of over three people was considered suspicious. Any gathering could be broken apart arbitrarily. It was a very hamstrung environment.”

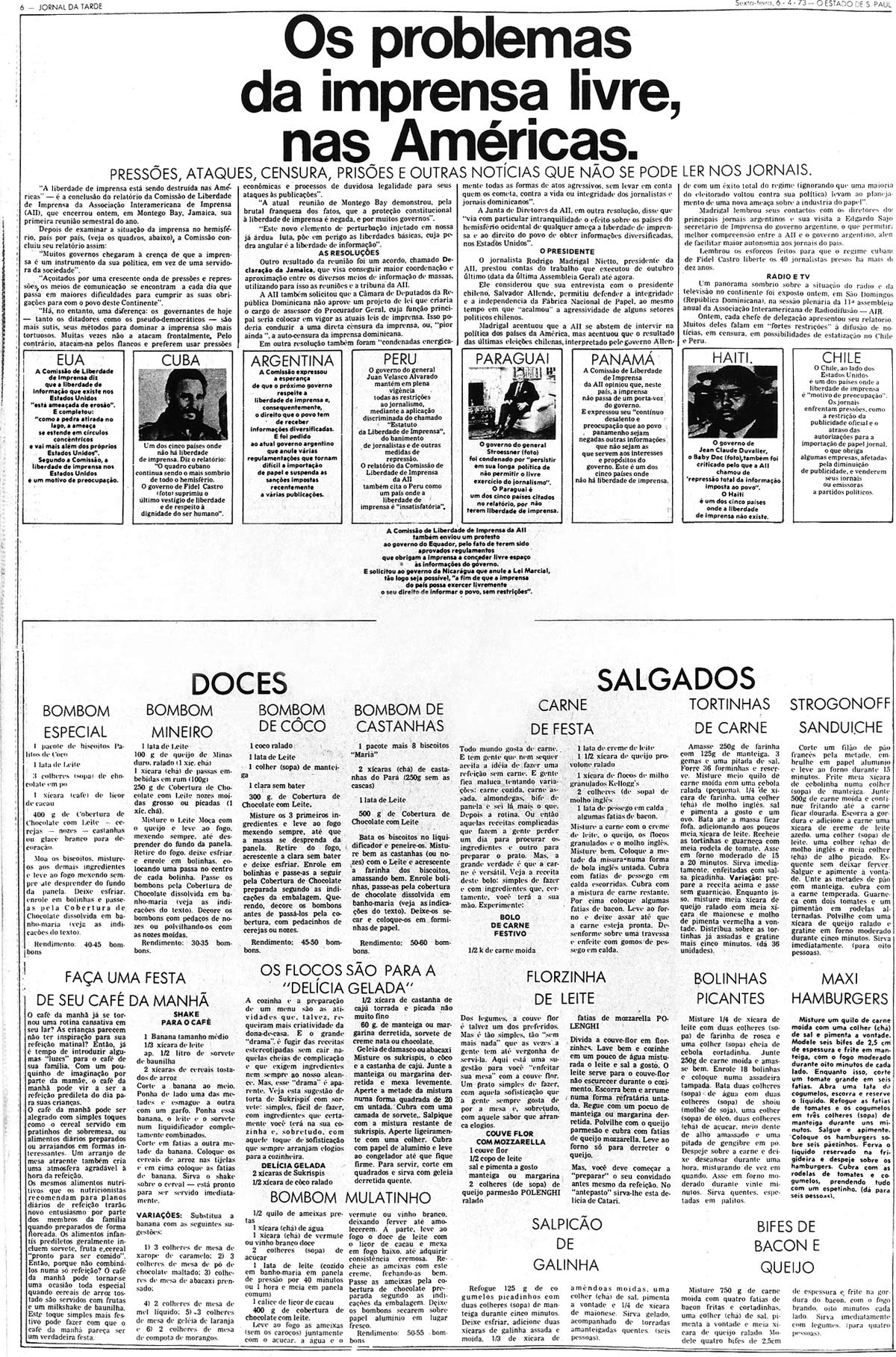

The cake recipes, which ended up becoming emblematic of that censorship, were mostly known to appear in the now defunct publication Jornal da Tarde.

They were often simple, usually featuring traditional cakes that would have been common knowledge to most Brazilian homes, such as cornmeal flour cake (known as fubá), or carrot cake. Another publication, Jornal do Brasil, regularly featured recipes for homemade bonbons in lieu of censored politics.

Since recipes were placed right before printing, wherever there were blank spaces left by variously sized texts that were removed, instructions for baking were often left incomplete, and the same cake would be repeated time and time again throughout one issue. In rare occasions, the title of recipes would goad certain politicians, making reference to their surnames in the ingredients. Often times, the resulting food was purposefully an inedible concoction, leading to disgruntled calls by readers who tried to prepare them. Some even assumed that the abundance of new recipes featured on the pages of Jornal da Tarde represented a new focus by the newspaper towards its female audience.

That couldn’t be further from the truth, confirms Adélia, who, as a young journalist also worked for Movimento, a smaller publication seen by many as resistant to the regime. During that time, she put together a special issue about the women workers in Brazil.

“We used the official government statistics available about the work of women in Brazil. There was clear portrait of the wage gap painted there, as well as the absence of women in leadership roles,” she tells me. “The content of that issue was 85-percent censored, including the official government numbers. The issue never went to print.”

Although this level of censorship and the cakes that came with it might seem to have stayed in the past, scars of Brazil’s dictatorship are still left unhealed. The number of victims murdered is only estimated, and many documents that bring to light the true degree of violence experienced at the time are still missing.

In 2019, the president of Brazil is Jair Bolsonaro, who has previously expressed his admiration for military colonels who were known for torturing political prisoners in a particularly cruel manner. He has placed military personnel in most top government spots.

Speaking to survivors of the previous regime and journalists who were working in newsrooms at the time, there is an unrelenting sense of unease hanging in the air.

“We are going towards dangerous times,” says Politi, when asked about the current political climate. “I don’t see prisons immediately happening but the military is placed in every single ministry. The vice-president is from the military. They don’t need to go back to the same violence of years ago, because these are different times. But it will get ugly if there is no resistance—if the parliament doesn’t notice that we’re headed towards an authoritarian regime.”

Fourteen days into 2019, the art collective És Uma Maluca was stopped from using voice recordings of Bolsonaro in an art installation criticising the horrors experienced during the dictatorship. In its place, someone reciting a cake recipe could be heard.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Warner Bros. Games -

(Photo by KRISTIN ELISABET GUNNARSDOTTIR/AFP via Getty Images) -

Skate icon Arto Saari