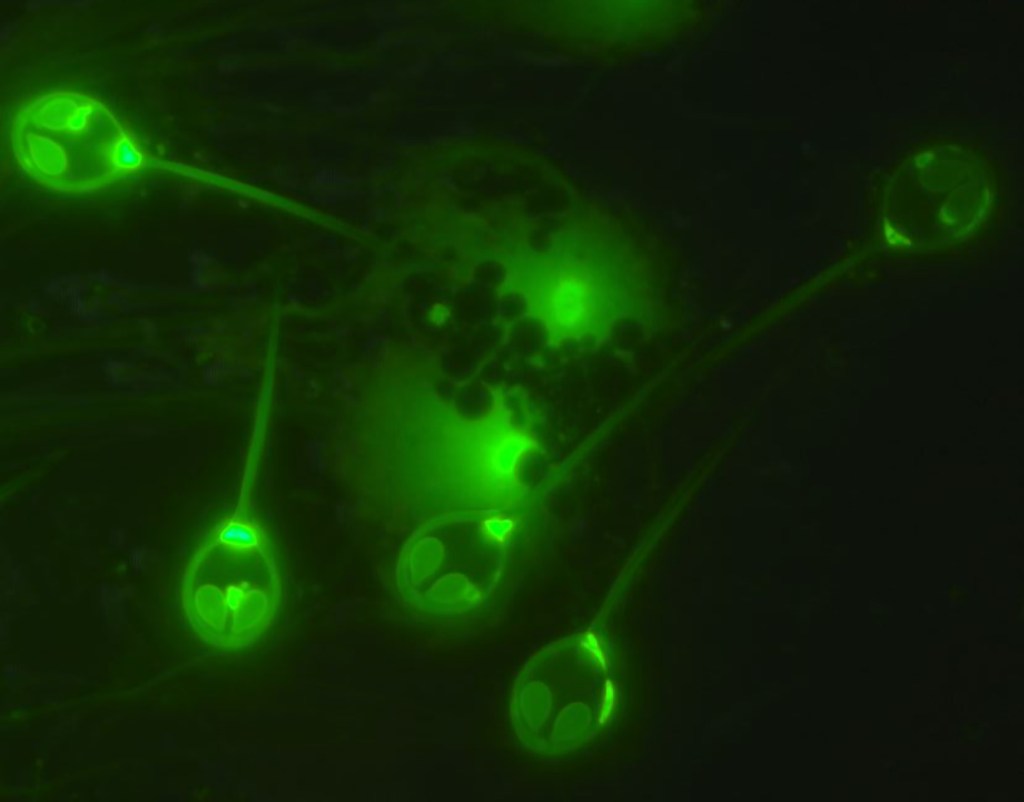

We’ll spare you graphic photos of the disease—this is nectrotizing fasciitis at a microscopic level. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Three decades ago, A. streptococcus was a bacteria that could cause a bit of strep throat, but not much else. Today, it can eat your flesh.

Its odyssey from essentially benign bacteria to flesh-eating terror was just chronicled by researchers at the Houston Methodist Research Institute in the largest bacterial genome study ever and was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Videos by VICE

A. streptococcus is a good bacteria to study for a couple reasons: It’s extremely common, infecting some 600 million humans each year, infects only humans, and, as I’ve already noted twice, it’s the leading cause of necrotizing fasciitis, a “rapidly progressive,” horrifying disease that the Centers for Disease Control says “destroys muscles, fat, and skin tissue.” Research centers around the world also have samples of it from the last 30 years or so—all those popsicle sticks stuck down people’s throats during strep tests were not in vain.

Let’s get this out of the way quickly—most people infected with the bacteria do not develop flesh-eating disease. Most get strep throat, which is easily treated with antibiotics. But if it somehow infects a different part of the body, which happens in as many as 3 percent of cases, it can be much worse—of that 3 percent, about 1 in 5 will have necrotizing fasciitis. Overall, you’re looking at several hundred thousand cases of flesh-eating disease each year.

In recent years, scientists have been warning about antibiotic resistance eventually leading to untreatable bacterial diseases and more pathogenic microbes. That’s not what happened with A. streptococcus, according to lead researcher James Musser—instead, it appears that four likely random “genetic events” led to the bacteria becoming more fearsome.

“I think it’s unlikely humans have contributed to this. These largely random events have produced a pathogen that’s better able to spread and cause disease, and they have been effective at elevating this organism to another plane, pathogenically-speaking,” he told me. “This used to cause minor pharyngitis, now it can be a flesh eater.”

To track its evolution, Musser sequenced the genomes of different samples of bacteria through the last three decades. The first two “genetic events” or mutations that originally gave the bacteria its flesh-eating capability came from bacteriophages, which are viruses that infect bacteria. These bacteriophages fundamentally changed strep’s DNA and made it produce two types of toxins. A third event, a single-nucleotide change in the genome (basically, a minor mutation), coded for the bacteria to produce another toxin.

“The fourth and final event,” Musser said, which occurred sometime around 1983, “was the acquisition of another foreign piece of DNA that encodes for a toxin called streptolycin,” which is key in the breakdown of human flesh.

“These events have taken a reasonably good pathogen and made it a much more virulent pathogen that is able to spread and cause disease,” he said.

So, why delve into the evolutionary history of a bacteria? Because by finding out what mutations made it more dangerous, researchers can be proactive instead of reactive, Musser said. Genomes can be cultured as infection strikes, and new medicines can be made more quickly. Another mutation could theoretically start an epidemic (if it becomes even more pathogenic or more transmissible), and if researchers can identify it earlier, they have a better shot at quelling it.

Beyond that, it’s cool to be able to tell the story of how a relatively harmless bacteria became so fearsome.

“The fact is, nowadays, we don’t have to guess about what transpired,” Musser said. “We can precisely delineate the exact molecular steps involved in this.”