Recently my boyfriend and I found ourselves in a ‘Shittest Song on YouTube’ session, involving a back and forth of Dune Rats videos and soulless Like a Version covers. After we watched Tash Sultana butcher “Electric Feel,” he decided to up the ante by playing a song I’d never heard before: “My Pal Foot Foot” by the Shaggs.

What followed was an insane cacophony of confused drums, nervous and cheap guitar melodies, and a stilted vocal melody. There was no bass, but maybe that was a good thing! Just out-of-tune, jagged strumming and a strained New England accent longing for a lost cat called Foot Foot.

Videos by VICE

A black and white image of three young girls, all with thick bangs, long wavy hair, and strange mystifying smiles, stared back. It was creepy in a backwoods culty type of way, and their unsettling grins were making me want to leave the room and think hard about my existence.

Dot, Betty, and Helen Wiggin were three sisters from Freemont, a small New Hampshire town, who during the 60s and 70s played under the orders of their father, Austin Wiggin. Though they didn’t rise to prominence until the next decade, the fact they reached any level of recognition dumbfounded me. They weren’t musicians who had a new vision for the next musical movement; just unpracticed kids. But what confused me most was that even the most untalented teenage player would still have an understanding of rhythm, and “My Pal Foot Foot” had none.

It was the worst song of all time made by the worst band of all time. They were disorganised, their lyrics slathered in absurdism and goody-two-shoes sunshine, and everything just sounded… wrong. Other songs on their first and only album, Philosophy of the World, weren’t any better. I asked my boyfriend to turn it off and let my ears heal, please.

But after finding out they were reuniting for the Wilco-curated Solid Sound Festival nearly 50 years after they formed, I decided to take a full listen to Philosophy of the World. Then something strange happened. I realised their dissonance was becoming more cohesive the more I listened to it, and in moments, my brain would rearrange the awkward guitars with the stumbling drums to make sense of it. I was starting to like the Shaggs.

And I’m not the only person who now thinks that they are the BEST worst band of all time. Frank Zappa allegedly said they were better than The Beatles, Kurt Cobain hailed their 1969 album as his fifth favourite album ever, and Lester Bangs called it “one of the landmarks of rock ‘n’ roll history.”

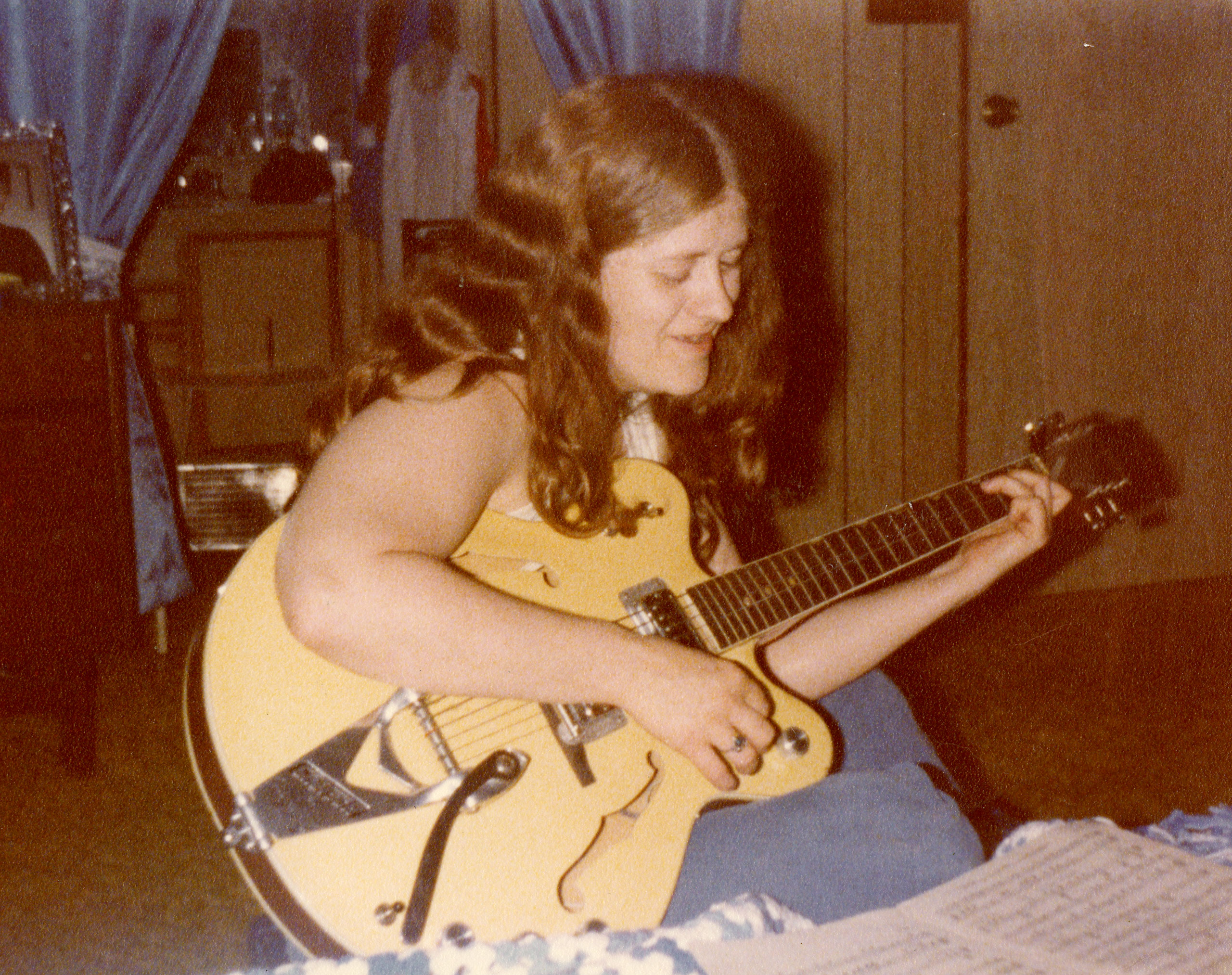

Image: Dot Wiggin

But their obscurity and one in a million shot to fame makes you wonder whether the Shaggs love is just a product of liking weird for the sake of liking weird, and I asked myself that too. Even Dot Wiggin, vocalist and songwriter for the Shaggs, has said she thinks the main reason why people obsess over her band is because of their story, not their sound.

And what a story! Of palm-reading predictions, a strict father-turned-manager, and small town sisters who fell into fame 12 years after the fact.

Austin Wiggins had two of his mother’s three palm-reading fortunes come true: he would marry a woman with strawberry blonde hair, and he would have two sons after she died. The third predicted his daughters would one day form a popular music group, so he gave it a shot. Taking his daughters out of school, he made them practice from sunrise to sundown, record an album, and play Saturday nights at the local town hall.

After his death, they quickly disbanded, then suddenly in 1980, NRBQ’s Terry Adams and Tom Ardolino found a copy of Philosophy of the World and were blown away. They reissued it on their record label, and the music industry could not shut their mouths about it. The Shaggs’ history reads like the treatment for the next film gunning for an Oscar (and indeed, there was a potential Hollywood biopic slated a few years ago).

Some have said they can hear the force of Austin in their songs, and there’s no doubt that he would’ve had an influence over the Wiggins girls as their looming and relentless figure. Many have pointed out that their music sounds almost painful and trapped, and in between the folds of squawking vocals, there’s a frightening story being told. It seems especially true of songs like “Who Are Parents?”, a track that feels like a stern finger-wag to children who don’t obey their parents. “We must remember / Parents are the ones who will always understand / Parents are the ones who really care,” the eerie, tense voice sings.

But Dot herself has said her awkwardly naïve lyrics are barely cries for help. In an interview with Rolling Stone, she said she had “always respected our parents” and that “there were a lot of kids who didn’t respect their parents and gave them a hard time so I was probably trying to get a message across to them.” So if there really weren’t any hidden tragic pleas to save them from the terrors of an authoritarian father, what’s left to like about the Shaggs?

The music, I guess. But really? Strip away their story and it’s hard to figure out if the music holds up on its own. In saying that, there are people in this world who genuinely enjoy listening to Metal Machine Music, and Philosophy of the World is a lot easier to understand than that monstrosity. There is, definitely, an unintentional experimental quality to the Shaggs, one that’s been compared to the free jazz compositions of Ornette Coleman, and it’s not like the sisters didn’t know what they were doing, contrary to popular belief.

It’s called being an accidental genius. They obviously weren’t trying to make proto-punk songs—they were trying to make traditional pop songs, but without the knowledge or skill to emulate that, all they could do was make sure they could follow a carefully fixed and laboured arrangement. Pianist, vibraphonist, and member of the Dot Wiggins Band, Brittany Anjou, has said the Shaggs’ melodies “break down to pentatonic scales, then they’ll go off the rails onto the ninth or the fourth. They would use the same key five ingredients and notes, but they’d completely fuck the order of it.” Again, accidental genius, and that’s a whole other charm of the Shaggs in itself.

Although what ultimately convinced me to convert to the pro-Shaggs side was something else: their ability to retain childish innocence in their discord. The Wiggin sisters were still very young when they were pulled out of school and whipped into a band by their father, and their songs reveal just how wholesome they still were, how unready for this world of music they had been thrown into. In “Philosophy of the World,” they sing about how “you can never please anybody in this world,” a rather cynical sentiment first off, but covered in messy instrumentation that actually feels… warm.

In the album liner notes, Austin Wiggin talks about the band’s unique approach to music and the poetic reasoning behind their off-key confusion. For Austin, the irrational drum fills paired with bizarre, emotionless vocals were less grating and more romantic: “Their music is different, it is theirs alone. They believe in it, live it. It is a part of them and they are a part of it. Of all contemporary acts in the world today, perhaps only the Shaggs do what others would like to do, and that is perform only what they believe in, what they feel.” I hate to say it, but he’s kinda right.

They’re definitely haunting—they’re too unnatural not to be—but mostly, they’re incredibly innocent, and we know that from both their story and their sound. Sure, Helen may be pummelling those drums for no reason at all, and Betty and Dot may be playing a guitar line that staggers and stops, but there’s a desire to be better, to actually be liked by the kids at the local high school who would throw soda cans at them when they played in concert. They wanted to be Herman’s Hermits, but they couldn’t. Instead, they produced what sounded like dilapidated nursery rhymes, fables with overriding messages, and odd Christian songs, because that was all that they knew.

The Shaggs aren’t the best band of all time, the best bands are purposeful and thoughtful about what they construct. But they’re worth listening to, for their unintentional duality: chaos and calm, and mess and beauty. It’s strange—the only person I’ve seen accurately describe how I feel about them is their father: “You should appreciate this because you know they are pure. What more can you ask?”

The Shaggs perform at Solid Sound, June 23-2 at North Adams, Massachusetts.

Images: Geoffrey Weiss/Light in the Attic press centre