It was a grey, Thursday morning when the 12 students approached the tall, yet otherwise nondescript vacant building. Mattie Shannon, a third-year student studying – aptly – disaster management, hadn’t slept much the night before.

Rising around 8 AM, nerves swirling in her stomach, Shannon had vacuum-packed a pillow and blanket small enough to fit in a tote bag, so as not to draw attention to herself and the group of students wandering towards Owens Park tower on that overcast November day. Otherwise, she was only carrying the essentials – Pot Noodles, a three-portion Tupperware of pasta pesto, her uni work and “bags and bags of chips and crisps.” Pulses racing, the students found a point of entry, climbed in, and let the rest in through a side door.

Videos by VICE

“We were like, ‘Oh my God, we’re in,’” says Shannon. “We thought someone would have stopped us. We didn’t actually think we’d get in.”

They had almost made it undetected until the group bumped into a cleaner on the first floor. Slightly shocked but reasonably unfazed at a large group of 18-to-21-year-olds in an abandoned building the cleaning staff used to store their supplies, she informed them that she would – unfortunately – have to let security know. The group ascended the tower, bike-locking all the doors behind them. Security didn’t catch up with them. They had successfully occupied the building.

The University of Manchester students – mostly first years – would occupy the tower for the next 12 days before their rent strike demands were met. They became the first students in the UK to win a 30 percent rent reduction for the first term, the largest rent reduction in the university’s history, and shone a light on the country’s increasingly profit-driven higher education system.

But the tower occupation wasn’t an isolated incident, or just a way to leverage a campus-wide housing campaign. It was a culmination of a term that saw Manchester become the epicentre of 2020’s student outrage. A decade on from the massive student movement against tuition fees, the uni became a focal point for the anger experienced by students across the UK, many of whom felt they’d become either cash cows or guinea pigs for institutions mishandling important coronavirus measures with profit margins in mind. It wasn’t just an unexpected viral load that stoked the flames. In their first term, Manchester University students also saw their peers fenced in their own homes without warning, experience alleged incidents of racial profiling, and tragically, a suicide.

Students in Manchester and elsewhere may be protesting the handling of the coronavirus pandemic but in reality, that’s only one part of a bigger problem plaguing universities that won’t magically disappear away once everyone’s been vaccinated: unis are organs of profit rather than institutions of education, and students are fighting back.

Manchester, a city in the north of England, is no stranger to grassroots action. In 1819, 60,000 people took to St Peter’s Field in the city to demand parliamentary reform. In response, the cavalry charged at the crowd, killing 18 people and injuring hundreds in what would later be known as the Peterloo Massacre. Today, the city stands as a Labour heartland at a time of majority Tory rule, a growing outlier after bordering constituencies in the “Red Wall” swung Conservative in the most recent election. In October, former Labour MP and Mayor of Manchester Andy Burnham fought back against government COVID restrictions placing the city in Tier 3, embodying a growing resentment towards the London-centric coronavirus legislation, and earning him the title of “King of the North”.

A few months earlier, at Manchester University, students were arriving for their first term. At that point, the virus had killed over 40,000 people in the UK and in the first five days of term, the number of students with coronavirus rose to 231. Despite universities knowing the risk of almost two million students travelling to campuses to live in cramped accommodation, desperate to socialise, students were assured that all the necessary preparations had been put in place and that it would be safe to return. Instead, thousands of students fell ill and were forced to isolate with people they had never met, in 12-person flats, with little access to proper food. Meals provided by the university were risible – one consisted of orange juice, oranges, and pots of orange slices, or Mugshot instant pasta. Courses moved entirely online.

Do you work at a university or in a university accommodation team? Do you know more about your university’s handling of students during the coronavirus pandemic? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can email tips@vice.com, or contact Ruby Lott-Lavigna at @RubyJLL or ruby.lott-lavigna@vice.com.

Manchester students’ collective action began, like many universities, in response to these mass outbreaks of coronavirus. Paying thousands of pounds to live, trapped, without access to many of the resources they had come to university for, the cracks in an underfunded higher education system started to show. Rent and university fees were collected from the students, but in exchange, they were given a virus and asked to not leave their room for two weeks, while not being able to socialise, go to the library, eat in shared space, or attend lectures or seminars. Groups like UoM Rent Strike, 9k4what and Student Before Profits were born, galvanising students to withhold rent from the uni, demanding better treatment for those isolating, and the ability to end their contract penalty-free. Hundreds of students began to join.

“Manchester attracts people who are radical,” says Shannon. “So it attracted people who’d protested previously and weren’t just gonna take [the university’s treatment], compared to some other universities.”

But it wasn’t just mass outbreaks that boosted this growing student movement, exposing a greedy education model that students believe is designed to use them as cash cows.

“There were other things,” explains Shannon. “The way we’ve been treated has been – I don’t know if it’s been worse but it’s definitely been publicly worse – the fences were a viral nationwide thing that everyone knew about

Manchester, and I think our management dealt with it so badly.”

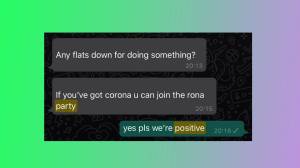

“The Fences” sounds like a Hitchcock film, and that’s not miles off the actual scenario. One morning, a few weeks into term, metal fences started to appear around the Fallowfield campus – a collection of seven student accommodation buildings. Students hadn’t been told why fences were being erected, and security staff were sheepish about answering questions. Green spaces were closed off. Amidst growing student dissatisfaction at the way they were being treated, students organised a last-minute protest, spreading the word across WhatsApp groups. Hundreds turned up within hours, eventually tearing down the fences.

But it wasn’t just the unnecessary and alarming security measures that students were protesting on that night.

“Earlier this semester this campus, we had a suicide,” Barnaby Fournier, a first-year student involved in the protest, said. “People in the flat opposite knew him quite well. They were absolutely distraught at the fences because they blocked off different accommodation, and they were like, ‘Have they not learnt?”

The university delivered a swift apology to the students. Nancy Rothwell, the Vice Chancellor said in a statement: “I sincerely apologise for the concern and distress caused by the erecting of a fence around our Fallowfield halls of residence today,” she said. “This was not our intention – in fact, quite the reverse.”

Nonetheless, Rothwell refused to meet with the rent strike campaign or offer the students.

Then there was the alleged racial profiling on campus. Zac Adan, a first-year, was walking to meet some friends on the same accommodation campus one night when he was confronted by security staff demanding to see his student ID, refusing to believe he went to the university. They pinned him against a wall until he proved he was an undergrad.

“They were so adamant that I didn’t go to this uni. It must have been based on what I look like, also known as my skin colour, my tracksuit, my hoodie,” he told VICE World News. “It was really really horrible.”

Racial profiling, fencing students in like animals, lack of support for those isolating, taking thousands of pounds in rent money from students who could be studying at home – it was a perfect storm. Not to mention, with ITV and BBC offices close by, students were able to get their message out quickly.

“I think, in quite a unique way, and in a very short succession of time, the students at Manchester went through a lot,” Larissa Kennedy, president of the National Union of Students explains. “They saw members of that community pass away. I distinctly remember seeing this sign that a student was carrying at a protest that said, ‘How many suicides does it take for UoM to show some compassion?’.

“For me, in that moment,” adds Kennedy, “it was very clear that this student movement is not only calling for rent rebates, it’s not only talking about economic justice but actually piecing together the fact that the very same systems that are producing students being fenced in against their will are the same ones that are producing the student mental health crisis, and are the ones that are producing the kind of horrific handling of student lockdowns.”

Kennedy has been supporting the movement from behind the scenes across the country. For her, and many involved in the student movement, it’s bigger than just one term of action.

“It’s incredibly exciting to see the student movement refusing to be constrained by a model of higher education that is consistently telling us that we’re these individual passive recipients of education,” says Kennedy. “Saying, ‘Actually, no, we are a collective learning community, that that has rights, and that can – through collectivism – not only change the education system but the world.’”

More than anything, the strike would bolster a growing movement of student resistance around the country. The action of the students created a blueprint for other universities, many of whom had launched similar rent strikes to varying levels of success. The campaign now plans to coordinate action across the country, and help other students achieve rent reductions and fairer conditions for the thousands of pounds they’re paying.

“I think this will have emboldened people,” says Shannon. “We already know that the rent strike that’s planned for January is bigger than the rent strike in September. Literally every protest is bigger than the one before. This is a national movement now.”

For the students of Manchester, this is just the beginning.

“I think universities thought that they could just do whatever they want to students, and that students really wouldn’t really fight back,” she adds. “We’re not going to just take things lying down.”●