Of the places queer people have transformed into sites to cruise for sex—from parks like the Central Park Ramble and Berlin’s Tiergarten, to sanctums like Provincetown’s Dick Dock and Fire Island’s Meat Rack—few have impacted the queer psyche like the public restroom.

“Mischief in public toilets left more traces in vice squad logbooks than in high literature,” photographer Marc Martin writes in the introduction to his new exhibition at Berlin’s Schwules* Museum, Fenster Zum Klo [Window to the Toilet]: Public Toilets, Private Affairs. (Full disclosure: I’m a Schwules* employee in the curation and exhibition department.) And while many modern queers would rather forget this chapter of their people’s sordid past, public restrooms are undeniably places where community and connection were kindled among us against unlikely odds. “These public toilets, whose history is intertwined with the lives and adventures of many gays, trans people, escorts, libertines, are also unlikely bastions of freedom,” Martin writes.

Videos by VICE

Martin has spent years collecting tens of thousands of historic objects and photos and conducting dozens of interviews about restrooms to try to capture the essence of that freedom. His Schwules* exhibition, selections from which feature below, includes both photos Martin staged himself to reenact cruising scenarios and selections from his historical collection to bring visitors through the history of toilet cruising. Some of those photos were shot in decommissioned bathrooms in Berlin subways with the blessing of the city’s public transport system, which, far from denying this aspect of their past, has embraced and officially sponsored the exhibition. Below, Martin spoke with VICE about restroom cruising’s historical and cultural impact, and how the history he’s surfaced has touched visitors in unexpected ways.

Your exhibition is called “Public Toilets, Private Affairs,” and chronicles the history of gay cruising and sex in public place in Paris and Berlin. Why do you think such a “sex history” belongs in a museum?

It’s the human dimension that matters most to me. These so-called squalid, gloomy and stinking places were incredible places of social mixing: gays and straights of all social strata, men of all ages, cultural and religious backgrounds came together there. That’s why—without ignoring the sexual dimension—I’m very proud to exhibit 150 years of history connected with public urinals here. It’s about bringing color and life again to these shadowy meeting places. That was my challenge with the exhibition: to restore the disturbing mix of sex and sensuality, utopia and urinals.

Your focus is Berlin and Paris. Why these two cities?

Public toilets around the world all tell the same story. For generations of men, they were a place for meeting and recognition. Don’t forget that homosexuality was banned by law for a very long time. In many countries, men who wanted to secretly meet other gays had no alternative but to visit public toilets, which seemed “neutral” in appearance. Even straight men could venture there and have anonymous sex without disturbing the façade of their heterosexual life, at least if they weren’t caught. The little stories inside the urinals differ only slightly, according to the era and the configuration of the buildings, but they’re all about the same shivers, the same fears, the same clandestine passions, the same furtive or symbiotic enjoyments.

Watch an interview with a gay couple who just had sex:

As you said, the “golden era” of sex in public toilets coincides with eras of LGBTQ oppression and stigmatization. Does that make “toilet sex” a story of sadness, a situation we should be happy to forget?

Fortunately, younger generations have the means to meet differently nowadays, at least in Western societies. But what about countries where homosexuality is still prohibited? The motivation for this exhibition goes beyond mere nostalgia. I wanted to restore the image of these get-togethers, to shed an optimistic light on the importance these places had for the LGBTQ community. In every city or village, public urinals served as an LGBTQ lighthouse, as a magnet.

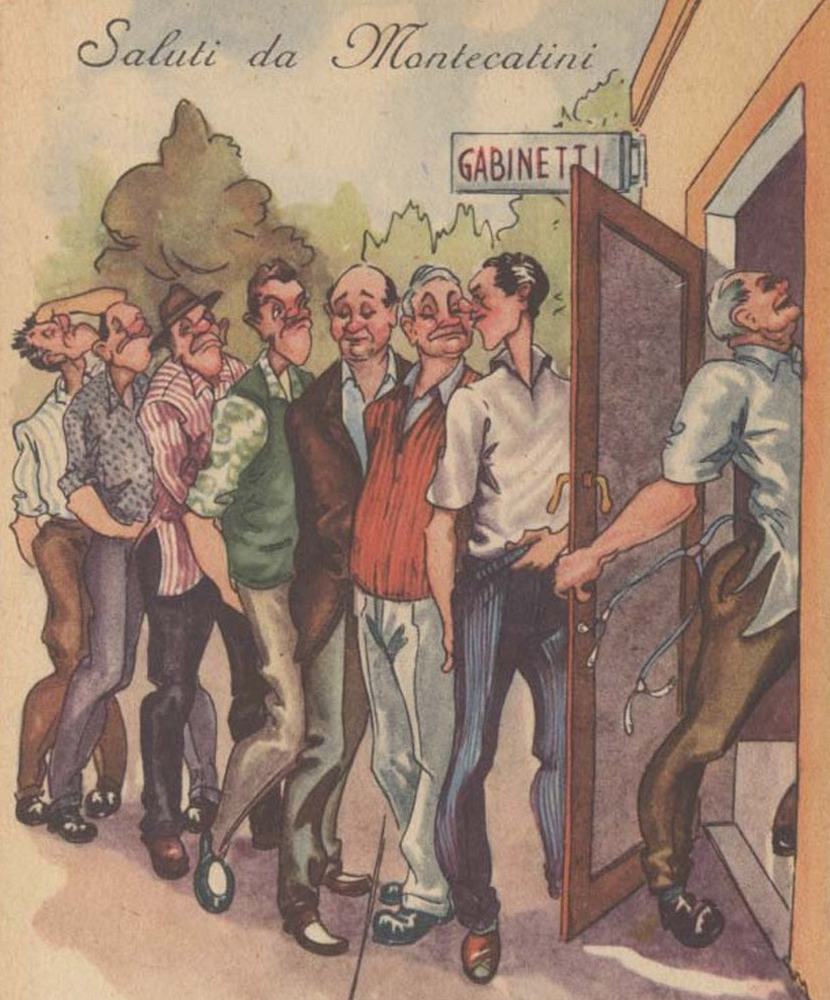

Public toilets have often been associated with murky perverts prowling around. Against that stereotype I chose to show, in my photos, smiling faces and blooming, horny guys in an exciting setting. If Marcel Proust, Jean Genet, Henry Miller, Paul Verlaine, and Arthur Rimbaud were inspired by the pissoir, it is because these dirty places also harbored mystery.

Most of the exhibition deals with men having sex in public toilets. What about women?

Sex in toilets has always been a guy thing. However, Schwules* had the brilliant idea to organize a meeting between Agnès Giard, a well-known French journalist and sex researcher, and Manuela Kay, a Berlin-based lesbian activist, journalist and porn director, for a public debate focused on the feminine perspectives of promiscuity in public places. And their point of view surprised me. They said women use toilets for sex for different reasons: to get away from men, to have a safe space, to close the door behind them. They would go there with someone they had met beforehand and knew, not with a total stranger. Plus, Manuala mentioned that you cannot stand at a urinal next to someone in a women’s toilet. If you sat in a cubicle waiting for some hot woman to walk in, you might be sitting there for years. In the discussion it became clear that lesbians have a very different history with public toilets, one that is not so central, but one that is important and worth further exploration. I only briefly touch upon it in my exhibition, with a section dedicated to the history of public toilets for women. When women were historically denied the opportunity to use public bathrooms—because of claims of indecency—they were basically kept at home. Because how could they leave the house for many hours without anywhere to pee? It’s not-so-subtle patriarchal politics.

What surprised you most about comments you received from visitors?

The reaction of women is captivating. It is a world that’s always been forbidden to them, and they’re fascinated to discover it, including the chapter in the exhibition on women’s toilets.

But the most touching reaction came from an older man I met the opening weekend, who cried discreetly with the exhibition’s catalog pressed against his heart. It was opened to a page with photos of restrooms in Berlin that have since been demolished. He said that sixty years ago, he’d met a stranger there—a stranger who would become his partner, now dead. It’s a beautiful story, and banal at the same time. What deeply upset me was that he had never before dared to confess to anyone the truth about his meeting the man of his life, precisely because it had taken place in a urinal! He then handed me the catalogue and asked me to write a dedication on that particular page. I asked him for his name and he answered with tears in his eyes: “Please, write: for Heinz and Jürgen.”

Interview has been condensed and edited. Fenster Zum Klo: Public Toilets, Private Affairs runs at Berlin’s LGBTQ Schwules* Museum through February 5th, 2018.

Kevin Clarke lives in Berlin and works for the Schwules Museum. He curated the exhibition Porn That Way and wrote the book Porn: From Andy Warhol to X-Tube.