There are numerous stories about the end times of MMOs—it’s an entire genre of essay, at this point. But what happens when an MMO comes back from the dead? Is it the same game players loved, or something different? Can the players even agree on what it is they’re resurrecting, and why?

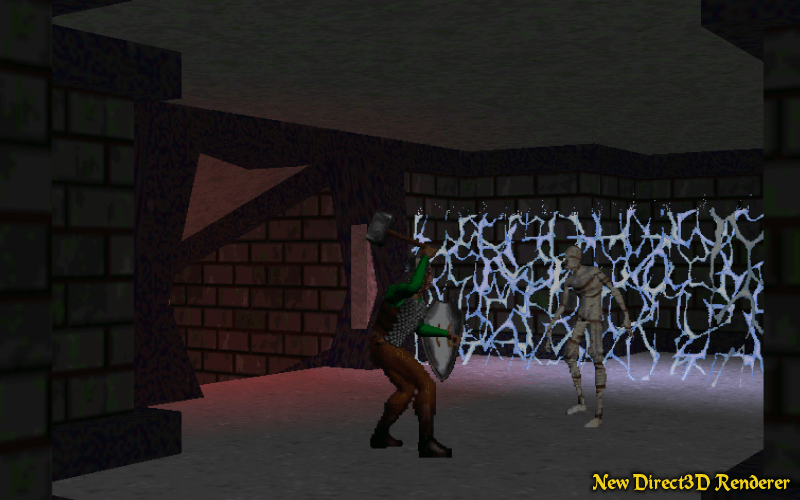

For hours a day and through most of my teenage years, I played a little-known game called Meridian 59. It was the first of its kind — a 3D, massively multiplayer online roleplaying game. It was like the missing link between archaic text-based MUDs, and EverQuest or World of Warcraft.

Videos by VICE

In this case, the apocalypse came on August 31, 2000. On that evening, Meridian 59 was shutting down. To honor the event, my friends and I had committed in-game suicide to get to the game’s underworld. We were throwing a dance party in the fires of hell.

Each of the game’s servers was numbered, from 101 to 109; they were shut down in that order. My home was 108. As we danced, the grim news came over the global broadcast chat. “Oh my God, server 106 is gone,” one player lamented. “We’ve lost 107,” said another a few moments later. Then, with a simple disconnection notice, it was all gone.

Yet somehow Meridian 59 is back—open source now—resurrected by fans on a quixotic quest to popularize something that few people ever liked to begin with. One of these servers just launched Biskalane, a fan-made expansion that added something Meridian 59 had not seen since 1997—a whole new region to explore.

But the expansion comes after a long debate inside Meridian 59‘s open source community about exactly what it means to preserve and continue to develop the game. A game can mean completely different things to different people, and what survives is less the original than it is different groups’ ideas of what Meridian 59 was—or at least what fans feel it should have been.

It turns out that to save Meridian 59, the amateur devs had to kill the game I loved. I appreciated the game because it obfuscated the numbers that make MMOs devolve into min-maxing races. It was opaque—a very 90s trait—in that it hid most things from you, keeping the focus on adventure and mystery. It challenged you to invent your own theories about how it worked.

When you attacked a monster, its increasingly intense cries of pain made told you generally how injured it was, but there were no damage numbers or health bars on enemies. The game also never told you how much experience it took to level up.

This led to players developing tons of competing theories about how to optimize over the years. Many players I knew during this time insisted that you’d gain power faster if you took more damage. Some of them stopped wearing armor as a result, taking utter beatings in the name of their faith, like some kind of cult of MMO berserkers. The theory turned out to be false, but the mystery lent the world of Meridian 59 a unique authenticity.

But on the new Meridian 59 servers, this fundamental design pillar has been knocked over. The previously hidden numbers have been unmasked.

When I hit a monster on the player servers, it tells me I did eight damage. When the monster dies, I receive 72 experience points, and an experience bar shows me the math on how far I have to go. It’s a more modern design, and it may sound like a small change, but this is not quite Meridian 59 anymore. I struggled with the changes to the game’s basic systems, like the exposed numbers and myriad other small updates that make the game feel more like modern MMOs.

I spoke about this with the creative lead—who goes by the name “Gar”— for the Biskalane expansion and the admin of the player-run server (simply named 103) on which it was deployed. I asked him if he feels something was lost with these changes, but he was unapologetic. “I do think something was lost in that move, but the era of mysterious mechanics ended with the 90s,” he said. “Can’t go back.”

That argument didn’t sway me but another one did, just a little. “Given that we’re open source, all the numbers and equations are public knowledge, but only to coders who know what to look for,” he noted. “All things considered, it’s probably better to give the average player direct access to those numbers, because otherwise they’ll just be annoyed by the process of sifting through code online.”

“One of the biggest conflicts our team had in its first two years was whether to remain ‘ Meridian classic’ or to move forward,” Gar recalled. “Eventually the classic Meridianites moved on to create their own server, which is something I think was inevitable from the very nature of open source.”

A more classically-minded open source server called 105 exists too, and it’s run by a group with very different priorities. They created a museum in the game that showcased deprecated content from the game’s various past eras. They overhauled the client to give it a modern interface. But they steered clear of messing with most of the core mechanics, or introducing any radically new gameplay or content—though it does expose min-maxable numbers just like 103 does. Even there, it seems the Meridian 59 I loved was not the one loved by others.

105 developer Delerium told me he loves the game too, but he’s fixated on the idea that “it’s had a lot of bad luck in its history.” He’s not as focused on new content or systems, but instead on the technology and infrastructure for preservation, out of a wild hope that somehow this archaic game will be discovered and treasured by future generations of players.

“I want to help it survive and maybe even give it a chance to compete with the more well-known MMORPGs one day, and a large part of the infrastructure work I do is to future-proof the server and tools,” he said.

He also talked about the split in the community between servers and code bases. “The game only has a few hundred players,” he admitted, “So perhaps it’s not ideal from a community standpoint to have so many servers.” Both 103 and 105’s server populations are a lot lower than most servers were in the 3DO days.

“On the other hand,” he added, “Players can choose where to play based on which content additions they prefer.” He believes that having multiple forks with an open source game is inevitable.

Still, the 103 and 105 teams work together on some projects, and cross-pollinate their accomplishments. It’s needed, because Meridian 59 had truly terrible development tools, especially for art and world building.

For more context on this, I talked to Brian Green, one of the developers who bought the game from 3DO. He and his partner relaunched the game in 2002, but “it was never a massive success.”

Brian recalled the limitations he faced when working on the game: “The notoriously awful level layout tool was an altered version of a freeware Doom room editor. Unfortunately, that editor didn’t support all the features of the Meridian 59 engine.”

Because of this and other issues, Brian and his partner sold Meridian 59 in 2009 to its original creators—Andrew and Chris Kirmse—for “a token amount of money.” Rather than invest further in it themselves, the creators just open-sourced it and handed it to the community that runs it today.

Article continues below

Everyone I talked to lamented the terrible level editor, too, but the community has done something about it where the previous owners couldn’t. “Over the last few years, contributors like Sha’krune and Delerium made the tools vastly easier to use,” Gar told me. “Creating a room has gone from an arduous thousand-hour task to something that can be knocked out in a few sessions.”

“The original room editor is a nightmare to work with,” Delerium agreed. “Last year I ported the popular Doom map editor GZDoom Builder to work with the room format we use.”

It’s made a huge difference. Even though the community has fragmented into different servers and builds based on taste, there’s clearly some collaboration and mutual respect between the teams. And the groundwork is laid for a very small revival, if they can just find a way to tell players about the game.

Last year, a community member showed the game in a booth at PAX to recruit new players. There’s also an actively managed Meridian 59 Twitter account. It’s hardly a media blitz, but the community is trying its best.

And of course, the tools work made the expansion possible. “The world felt unfinished, so I believed it important to create an expansion,” Gar told me. “It took multiple years to get everything worked out and get the team on board with such an ambitious idea.”

When word of mouth reached me about Biskalane, I installed the game for the first time in years. The added content—particularly the new region—nails it. Meridian 59 has always been a challenging game, and Biskalane demands a lot of players. There’s a more robust endgame than ever before. So many old bugs have been fixed.

But I still found myself longing for the classic Meridian 59 experience, with no player changes. Gar pointed out that there are two servers run by the game’s creators with the classic, unmodified codebase. I created an account and logged in to these classic servers, but both were empty. Everyone had left for the open source frontier.

Nevertheless, I spent the weekend vanquishing enemies. I hoarded loot in my vault, never to be seen by anyone. Interacting with non-player characters, I felt like Will Smith speaking to store mannequins in I Am Legend.

Ennui set in. It turns out the world I knew did come to an end on August 31, 2000, because the memory of Meridian 59 I harbored was my own; other people preserved a different game in their memories. Defeated, I returned to servers 103 and 105.

732 more experience until I level up.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: HBO -

Screenshot: Bethesda Softworks -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Screenshot: Ubisoft