On an October morning in 2018, in a town on the outskirts of Moscow, senior police investigator Evgeniya Shishkina was leaving home when she was ambushed by a gunman. Lieutenant Colonel Shishkina took a swing at her assailant. He slipped, but shot her in the stomach. As she lay on the floor he got up and shot her in the neck.

Shishkina’s murder is thought to be one of the first cases of a lethal hit ordered on the dark web. Russian police and an investigation by the BBC allege the shooter was hired on an illegal drug trading platform known as Hydra, by a Russian hacker who ran one of its online drug shops.

Videos by VICE

As Russian police continue investigating the murder of their colleague, the sheer size and reach of Hydra, which serves up drugs to Russians and post-Soviet republics, has come under the spotlight. With its origins in Russia’s hacking underworld, the site has emerged to become the largest online drug bazaar on the planet. But it is also a dark web drug enterprise like no other.

Hydra has a whopping 2.5 million registered accounts and 400,000 regular customers, according to analysis last year by investigative news outlet Project. The largest Western dark web market, AlphaBay, which closed in 2017, was thought to have 400,000 registered users at its peak.

According to Project’s research, between 2016 and 2019 Hydra’s 5,000 shops contributed 64.7 billion rubles ($1 billion) to the platform through sales commission, enhanced shop profiles and shop rents. This dwarfs its dark web counterparts in the West. The total volume of sales going through all Western dark web markets between 2011 and 2015 was $191 million (12 billion rubles).

It’s not just bigger. Hydra represents a new kind of dark web marketplace. Much of Hydra’s setup will look familiar to dark web drug buyers: Logging in through the Tor browser, perusing an eBay-style catalogue of brain-tickling chemicals, forums and customer reviews, paying via cryptocurrency, a small commission out of each sale. But there are innovations.

Hydra has a strict way of doing business and code of conduct overseen by a central hub. While in other markets vendors pay once to open an account, on Hydra every one of its estimated 5,000 shops has to pay a monthly rent. This starts at $100 a month and rises to $1,000 a month for an enhanced account, known as a Trusted Seller, whose ads appear on the top banner. Trusted Sellers must have racked up at least 1,000 transactions and customer disputes should not exceed seven percent of the total number of orders per month.

Hydra’s admins have learned from previous dark web drug markets and know that trust is key, so the marketplace has a sophisticated quality assurance set up. Hydra has its own team of chemists and human guinea pigs to test each product and medics on standby to give safety advice. There is a subforum where these test results are posted, complete with graphs, analysis, and photos. If the gear’s not up to scratch, the administration hands out penalties. Anyone trying to pass oregano as high-grade chronic will get kicked off the site. No fentanyl is allowed, and neither are weapons, hitmen, viruses or porn, although drugs, fake passports, dodgy SIM cards, and counterfeit cash are sold. On the whole, these rules appear to be obeyed, although the investigation into Lt. Col. Shishkina’s death may prove otherwise.

But Hydra’s biggest calling card is how it’s crossed the digital realm into the real world.

Because with the help of an invisible army of young couriers, Hydra is monopolising Russia’s traditional street drug trade. Like a real life video game, the online stores on Hydra employ drug dealers known as kladmen (“treasuremen” or “droppers”), whose job is to stash drugs in GPS-tagged hiding spots ready for pick up by online buyers. It’s a street-tech workaround in a country where the postal system is slow and unreliable and regular street drug dealing is highly risky. It’s basically Pokémon Go for drugs.

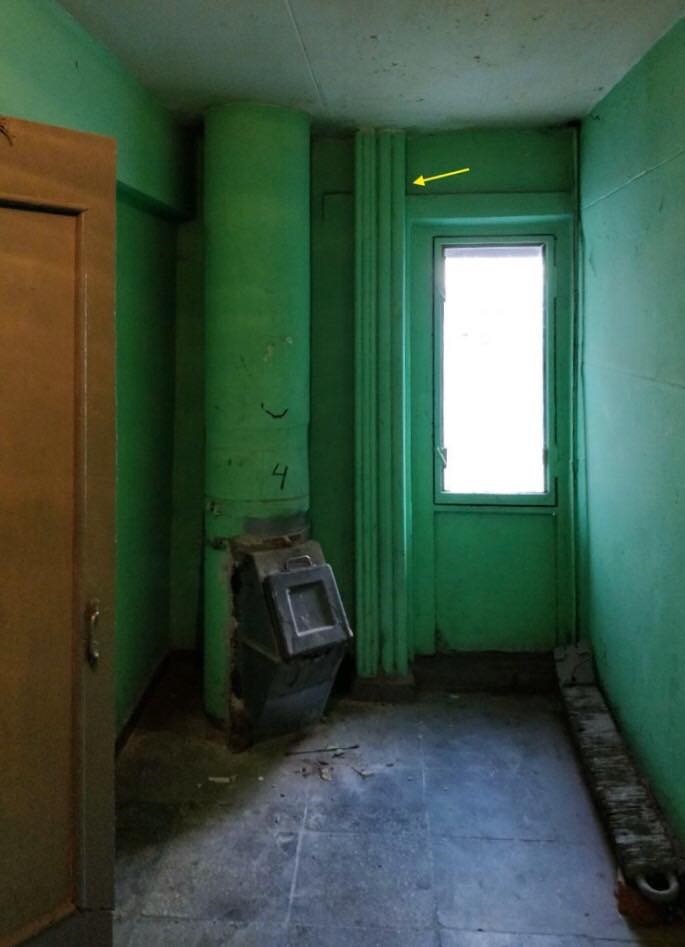

Dead drops from Russian drug web marketplaces were first reported in 2014, but under the auspices of Hydra the system has proliferated. At any given hour in Russia’s cities and towns, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of suspicious-looking characters scurrying around parks and city centers burying stashes of drugs such as mephedrone, cocaine, MDMA and weed, ready to be picked up by buyers. These dead drops can be anywhere from tree hollows, street bushes, round the back of apartment blocks or electrical transformer boxes, in crowded public locations, near metro stations or local forests.

On completing the online transaction, buyers are sent coordinates, photos, and directions where to find the buried treasure. For example: go to the north entrance of the park and look under the third tree on your left. After going on this little quest, buyers have got 24 hours to confirm they have the goods and leave a review. And with business booming, Hydra has created a whole new profession for young Russians.

Galina* started work as a dropper “out of desperation” in Moscow five years ago when she was in her mid 20s. I contacted her with the help of a middleman with experience of Russia’s street and cyber drug world. (*Galina is a pseudonym and neither her nor the go-between wanted to be identified.)

“I had a loan, a lot of debts, and I’d suddenly lost my job. I urgently had to find a way out,” she told me over encrypted chat. “I was already an experienced drug user and I had been buying from online sites so I decided it was time to take a chance and try my hand at the business.”

Before starting work, droppers must pay a deposit of around 6,000 rubles ($80) to the shop through bitcoin or a Qiwi wallet, to make sure they don’t run off with the first stashes they are tasked with hiding. They in turn get paid via the same anonymous means. Once they have hid 6,000 rubles worth of treasures, they can start earning.

Galina was paid commission depending on the weight and type of drugs on each drop. The cheapest were hash and grass, 300-400 rubles ($4-5) per gram, while cocaine and mephedrone paid the most, 600-1000 ($8-14) a gram. She said she dropped between 10 to 20 “treasures” a day. But there were times she did 30 or 40. At first she worked with hash, MDMA, and amphetamines, then almost exclusively with mephedrone, a drug that has become increasingly popular in Russia over the last decade.

She got her drugs from what she calls a “master drop,” a large stash of anywhere between 20 to 500 grams, hidden deep in the forest, far from Moscow.

“Sometimes the stuff comes pre-packed, but sometimes we had to divide it up ourselves,” she said. “For instance, you pick up 200 grams of mephedrone. Take it home, re-pack it there. This is a very long and boring exercise, but I could decide how many drops of what weight I wanted to do and it was very convenient. Usually I would make 10 drops of one gram, 10 of two grams, and go lay them out, leaving the rest till next time.” Noting where the different packages were hidden, she sent the coordinates to the shop’s head office. As soon as someone makes an order, they get the GPS coordinates.

The second task of a dropper is taking a photo and writing a description and uploading the goods onto the shop site. Ten packages usually took her 30 minutes. She said sometimes things went wrong with the upload: “Tor freezes, the internet disconnects… and then you have to start all over again.”

To accompany Russia’s new, highly illegal profession, there is a handy guide. All is revealed in the Kladman’s Bible, a 26-page how-to guide for Hydra’s droppers, which can be found lurking on various drug forums on Hydra. An earlier version of the bible was circulated among droppers on RAMP, Hydra’s smaller predecessor, the first site to pioneer this way of dealing on a significant scale. But since then it has been updated and revised.

The bible advises droppers to use encrypted phones (so police cannot track previous drops) and map-downloading tools (to mark drops without having to go online). Unsurprisingly it tells grasshopper-level droppers to avoid drawing attention to themselves. “You need to look normal, average, but neat, and most importantly, move confidently, calmly. You don’t have to turn your head like an idiot to focus your eyes on a specific subject,” it says. “Don’t act suspicious or be in a hurry; don’t go around dressed like a punk or a hobo; and by the same measure don’t go in a suit and tie either. It would be weird if someone sees an office manager crawling around the bushes.”

Good hiding places are places “where the customer has to reach their hand around somewhere,” such as tall bushes and electric transformer boxes. Bad places are near schools, cemeteries and police stations (because they can draw unwanted attention), apartment block courtyards (because the gates might be closed when the customer gets there), and even gutters (unless packages are waterproofed).

“There are two ways of doing your rounds. You can either go for a walk, looking for places to hide the stuff, making drops and taking photos as you go. This is faster, but riskier as you’re always walking round with a backpack full of gear,” Galina said. “The other way is walk around without the stuff making a note of possible hiding places as you go, then go back to them afterwards. This takes more time but you can uncover more hiding places this way and it’s less bait. The speed at which you do your job is not as important as efficiency.”

So who makes up Russia’s new army of drug couriers? Lawyer Arseny Levinson runs the legal aid service Hand-Help.ru, which offers advice to people arrested for drug offenses. He says all sorts of people become dropmen, but most commonly it’s young people. According to his analysis of Russian Ministry of Justice statistics, more than half of those convicted of drug trafficking in 2018 were 18-25 years old and students. He says this is a lot to do with Hydra droppers.

“It’s the same kind of people who work at Yandex Pizza Club,” said Levinson. (Yandex is a big online food order and delivery service in Russia.) “In fact, the adverts for droppers on Hydra are almost exactly the same: flexible working hours, fit around your study time.” While Yandex promises at least 1000 rubles ($16) a day, a typical dropman will earn three times that.

“Probably half of them have some problematic drug use, didn’t have the money for it any more so turned to this to support their own dependence,” Levinson continued. “The other half are students in rural parts of Russia with no other ways to earn money. In Moscow you can get a job delivering pizza, but in the provinces there’s no such opportunity.”

Eduard* was interviewed in Altai prison in Siberia last year by a local news site while serving a seven year sentence for drug dealing. He decided to become a dropper after leaving the army and spotted the advert to be a kladman while buying drugs online. At one point he said he was doing 70 drops a day, using the money to fit out his apartment with brand new furniture. Eduard said for him being a dropper was not just about the money: “There was something else involved in all this work. Namely adrenaline. That feeling when you balance all the time on the verge of being caught.”

Another former dropper, George*, told BBC Russia he started out aged 24 in Nizhny Novgorod, earning three times the average salary for the city. Because of his love of forests and parks, he used those to bury his drug stashes at night when it was quiet.

It’s hard to tell precisely how much of Russia’s drug trade takes place over the dark web. But all the evidence points to something of an online takeover.

“This is now an exceedingly common way to get drugs in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States,” said Patrick Shortis, a cryptomarket expert at the University of Manchester. “Hydra is hugely significant in Russia and by far the most popular Russian-language market for this kind of activity.”

Shortis said Hydra is a more multifaceted and harder to contain beast than other online drug market sites. “Vendors must recruit droppers from multiple geographic areas to expand their business,” he said. “They may also recruit customer relations managers to handle customers who are requesting information on their drops. This means that whilst vendors in the West are often thought of as one person or a small group, vendors we see listed on Hydra are much more likely to be representative of a larger network of actors.”

Shortis said that Hydra is a lot more visible to police, but that does not make it easier to investigate. “Those working at the retail end, who make the largest amount of drops, have a much higher chance of being caught. Yet when they are, they may know little about anyone else in the vendor network and consequently, the law enforcement investigation may end with them,” he added.

It’s also a lot more public-facing. “The fact that droppers and customers are wandering around Moscow or St. Petersburg delivering or collecting packages makes the Russian online drug trade much more visible than its western counterpart. This is very different from western cryptomarkets where the privacy of the delivery method mitigates public awareness of online drug markets.”

With every new shift in the criminal world comes a new bunch of parasites. Apart from the police, the new natural enemies of the droppers are a group of drug stash thieves known as the “seekers,” who make it their business to hunt down drugs that have been hidden by droppers. For droppers who either get tracked by seekers as they make drops around town or whose hiding places are easily found by someone on the lookout for stashes, seekers can mean the sack. If buyers go to a hiding place that’s already been emptied of its stash, they will complain to Hydra’s administrators, who will ditch droppers who keep on getting stolen from.

As the Kladman’s Bible says, droppers need to be extra careful hiding drops around metro stations because “even though it’s more convenient for customers, it’s also more convenient for seekers.”

Seekers love the long Russian winters, when the snow reveals a myriad of hiding places across towns, cities, parks, and forests. If they follow a trail of footprints in the snow to places people don’t normally go, seekers know the tracks could well lead to a bounty of hidden stashes.

Hydra’s young dropmen aren’t just worried about the cops and the seekers. There’s also Russia’s violent anti-drug activists.

The City Without Drugs (CWD) movement was started in Yekaterinburg in the early 2000s by a man, Evgeny Roizman, who later became the city’s mayor. Over the years the group has been accused of kidnapping addicts, chaining them up to make them go cold turkey, mob ties, and racism and xenophobia towards immigrants. Roizman insists he’s not against immigrants, only the ones doing crimes. But now CWD is refocusing its aim.

I met Alexander Shumilov, who runs a City Without Drugs’ chapter in Irkutsk, at the group’s HQ in Yekaterinburg. “We don’t try to save the world, we do what we can,” he told me. He said Hydra has changed the nature of drug dealing, so Shumilov’s targets are now very different. “We’ve got a database of dropmen and we shake them down. Before when we were dealing with heroin, of course it was mainly gypsies and Tajiks, and every drug user was a seller as well. Now it can be Russians, anyone. It’s not just drug addicts making drops, it’s kids recruited on social media. They’re not pros, they don’t wanna go to jail, so they spill the beans.”

But since the dropmen don’t know their actual paymasters, it’s not clear what police or vigilante groups such as CWD will achieve beyond clearing out a few low-level errand boys and their stashes. A November police operation which netted nearly half a ton of various substances failed to catch even one store proprietor—just seven couriers.

That brings us to another interesting question. In many parts of the world, law enforcement’s attitude to drugs has been if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. Russia’s old anti-drugs division, the FSKN (Federal Narcotics Control Service), was so corrupt it earned the nickname Gosnarkokartel (‘drug cartel agency’, a play on ‘drug control agency’) before finally being dissolved in 2016. Given what we know about Russian hackers and the Russian mafia, not to mention corruption within the DEA in the Silk Road case, could it be Hydra has friends in high places?

“The collaboration of shops with law enforcement is a myth, perhaps thought up by the law enforcers themselves,” Galina said. “How would that even be possible? There are times when they accidently catch a store’s admin whom they force into working for them, or they bring someone they’ve previously caught into the store. But such cases are rare. There’s no official ‘roof’ [protection] by the police to shops, because it’s thanks to the Tor network that the administration remains anonymous and elusive.”

Nevertheless, while the dark web drug lords remain untouchable, that doesn’t mean enterprising officers can’t get in on the action themselves.

“The narco-business in Russia is known for never being far from the siloviki [security officials],” Levinson explained. “Whereas before setting up drug users was the main form of entrapment, now the police are opening their own stores and setting up their own dealers. We keep hearing cases about this, for example in Khakassia. That way you can make a little money, and maximize your own stats by uncovering more ‘criminal groups.’”

In November, an ex-policeman in Khakassia, eastern Siberia, accused his superiors and the head of the region’s counternarcotics squad of reining over a drugs and protection racket centered around the online store ‘Killer Dealer’, which specialized in synthetics. After allegedly uncovering the scheme, 36-year-old Yuri Zaitsev was himself charged with taking payoffs from drug dealers. Zaitsev then posted a YouTube video claiming the narcs, working together with the FSB, used their position to gather intel on disposable dealers and busted them, giving the impression they’re leading a tough fight against crime. When one of their dealers was caught, they personally intervened to have the charges dropped. After posting the video Zaitsev was charged with revealing state secrets, and his wife Elena told reporters she fears for his life and that he’ll suffer an “accident” in prison.

Of course, this wasn’t just one crew of cowboy cops on the remote frontiers of Siberia. For example, last July it was reported that two police chiefs were arrested for running an online drug ring in Moscow. And those are just a few such cases we know about.

“It’s possible a lot of dropmen were set up,” said Levinson. “If someone says, ‘that’s it, this is the last time,’ there’s no more profit for the store and they get sold out to the police.”

Russia now has more prisoners serving time for drugs than any other crime, a slot formerly occupied by murder.

“It’s partly because of the dropmen, but also because of the toughening of drug policy over the past ten years, with harsher and harsher sentences,” Levinson explained. “Drug offenders are the biggest group because there’s so many of them and they’re sitting [in jail] for longer. It’s harder to get out earlier for drug charges, like with terrorists and child molesters. But it’s not only those hiding drugs that are imprisoned, but also those who pick them up: the dropmen and their customers.”

With so many treasures to be found, Moscow’s full of suspect characters making or picking up drops. Whereas the dark web made things safer to a certain extent, you’re still facing jail time walking around with an eighth in your pocket.

Hydra’s roots go back to the hacking forums that sprung up on the Russian-speaking internet in the late 90s and early 2000s. Back when I was serving time in the UK, I shared a cell with Misha from Moscow. Misha was doing five years for fraud conspiracy after using a virus to siphon off £3m (then around $4.5m) from compromised bank accounts to ones controlled by him and another guy from Kazakhstan. He got caught, as usual, by one stupid mistake: one day, he forgot to turn on the equivalent of a VPN or Tor on his laptop, so they traced his IP address and slapped handcuffs on him as he was boarding a flight to Kazakhstan. Still, quite enterprising for a 20-year-old.

There are two reasons Russia keeps spawning top cybercrooks like Misha. The first is that Russia has a lot of very smart, educated people. Russian universities produce great scientists, engineers, programmers, and mathematicians. Unfortunately it doesn’t produce them all great jobs. The second is that the government actually uses hackers as privateers to do its bidding, which is why the same names pop up in cybercrime and national security investigations. So long as you don’t harm Russian assets, it’s open season on the West. Go, steal for Mother Russia!

A few of those sites grew from being a place for sharing credit card details to ones where you could get drugs, and from that community of hacker-psychonauts came RAMP, Russia’s version of Silk Road. RAMP (the Russian Anonymous Marketplace) arrived on the scene in 2012, building a platform where instead of messaging users back and forth you could simply browse the catalogue and press buy. Unlike the libertarian rhetoric bandied around on Silk Road, RAMP refused to support any agenda, knowing what happens to such outspoken parties in Russia. And unlike Silk Road, instead of taking commissions from each sale it charged every prospective drug merchant a flat tax for doing business on its platform.

Hydra was born in 2015 as a merger of two smaller forums, Legal RC and Way Away, both specializing in synthetics. According to an investigation last year by Moscow-based online newspaper Lenta.ru, RAMP was launching hostile takeovers, mobilizing its hackers to launch DDoS attacks on rival sites. Legal RC and Way Away were the last ones standing, and they had to stick together if they wanted to survive.

But RAMP had major weaknesses from the outset. One, its refusal to commit to anything political extended to a ban on advertising. Two, it didn’t allow the sale of mephedrone or synthetic cannabinoids (spice). It’s one of those strange prejudices drug users have against each other: no matter how much society looks down on your intoxicant of choice, there’s always someone worse. Hydra meanwhile had chemists working for its shops cooking up these novel substances, and a direct line to precursor suppliers in China, allowing it to corner the market in poorer areas where synthetics are more popular. RAMP’s ignoring of that demographic gave Hydra an edge.

Eventually, RAMP tried closing its blind spot, poaching Hydra’s chemists and suppliers. Hydra struck back, shutting down the site with a string of DDoS attacks. A classic turf war broke out in cyberspace, except instead of car explosions and drive-bys it was a bunch of nerds hurling botnets at each other.

The constant shutdowns were costing RAMP’s dealers a lot of money, so they began leaving in droves. The admins started losing it and went into full Stalin mode, reading their members’ private messages to check who was still on the team. One disloyal store was sold out to the feds as an example to others. Hydra cracked RAMP’s code and doxxed its admins. The final blow was when a bitcoin exchange operator and alleged money launderer was arrested in Greece and $170 million disappeared, including most of RAMP’s slush fund to pay mercenary hackers.

By summer 2017 RAMP was dead and the MVD (Russia’s interior ministry) released a triumphant statement claiming credit for smashing Russia’s biggest online drug market. In reality, although the police had unearthed some of RAMP’s wholesalers, it was Hydra that had killed them off. Either way, with its main competitor out of the way, Hydra moved to consolidate its gains. It embarked on an aggressive publicity campaign, posting videos on YouTube, buying databases of phone numbers and spamming them with texts, and absorbing existing drug rings, inviting them to join the party.

Last year it was reported that RAMP’s founder and chief admin Darkside, who sported an Ed Norton in Fight Club avatar, died of a heroin overdose in Nizhny Novgorod in 2015.

Hydra now has thousands of online drug bazaars catering to every corner of the Russian Federation, from Vladivostok in the Far East to the freshly-annexed Crimea. There are even a few branches and shops operating in Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan and other former Soviet territories. The way Hydra’s managed to so effectively take over and monopolise the business makes it look cartel-esque.

In the old days, you needed heavy-duty political or underworld ties to make it in Russia’s narco-business. Cocaine has been coming in through St. Petersburg, allegedly protected by powerful figures, since at least the 90s, although its high price has put it out of reach of most Russians. Meanwhile, a heroin pipeline was set up from the poppy fields of Afghanistan through the ex-Soviet republic of Tajikistan: kilos of heroin were hidden onboard military planes, then distributed through the Tajik diaspora.

Now, the rise of new synthetic drugs and online drug markets such as Hydra has meant just about anyone can set up shop as a drug dealer. On Hydra, most shop owners are former minor players within Hydra’s world. Three years ago Galina decided to progress from dropper to shop owner.

“Once you understand how everything works and decide you’ve had enough of feeding off the breadcrumbs off the master’s table, you’ve just got to save up some money,” she said. Galina told me prospective shop owners only need around 60,000-100,000 rubles ($800-1300)—for start-up costs to buy drugs and paying rent—to set up a shop on Hydra.

But where do the shops get their supplies? If you’re not on first-name terms with an opium-slinging warlord, fear not: everything shop owners need, wholesale and warehouse style, is on Hydra. Cathinones and other synthetics are now massive in Russia, and Hydra sells do-it-yourself spice and mephedrone making kits, along with the raw ingredients imported from China. Galina’s chemists cook up these substances, but she stays out of the Heisenberg side of things.

“I’ve got my own production chain. I don’t touch the process myself, so I can’t tell you how complicated it is. The chemists find what they need through their own channels; I only allocate them funds.”

According to Galina, vendors on Hydra are more likely to collaborate than compete with each other. “We buy goods from each other; we warn one another about unreliable employees and police threats,” she said. “Yes, sometimes it’s a shame when someone brings goods to your city at a much cheaper price; that can hurt your sales. But people choose not only on the basis of price, but also take into account the convenience of drops, the reputation of the stores and their specific wares. Shops try to occupy their own specific niches. In Moscow for instance, there are quite a few shops that deal with cocaine and expensive mephedrone, and there are shops that basically only sell marijuana. I don’t have to split anything with those guys, for example.”

Like any business, the shops have a division of labour: someone runs the stash house, someone does accounting, someone tends to the ganja plants, and so on. Galina has a helper who takes care of admin when she’s not around. But the life of a dark web vendor is a busy one and she rarely gets to unwind.

She now employs a team of six young couriers. “A good dropper must first of all be honest and responsible,” she said. “Not everyone can resist the temptation to use the product or sell it on the side. This is the main problem when finding workers. You can teach anyone how to make good drops over time. But you can’t teach moral principles.” There were a few couriers she employed who lost every other drop, so she quickly showed them the door.

I ask Galina about her life outside Hydra. She says she has very little free time. “Most of the time I’m busy running the shop. I’m a very cautious person and I like to keep everything under control. It’s hard for me to imagine the day when I can delegate authority to someone else and stop dealing with business directly. But of course I need to relax. I visit bars and cafes, watch TV shows and documentaries. Sometimes I go visit friends in another city. I’d like to take a road trip across Russia one day, but right now it’s just not possible.”

She may have little spare time, but at least Galina has managed to stay out of jail, unlike the droppers who make up some of the 19,000 people who were convicted for drug dealing in Russia in 2018.

Although one Hydra shop owner interviewed last year said he sometimes kept his droppers out of jail by bribing police officers 500,000 rubles ($6,800) to drop the charges, some are not so lucky.

“That’s a cute picture,” I said, looking down at a drawing of Pikachu.

“Yes, he tried hard for his sister,” beamed Oxana Orlova, who lives in Kirov, a city in the Volga region east of Moscow. “He’s a very creative boy. He loves writing poetry, music. As for the youngest one, she still doesn’t know anything. She thinks he’s gone off to study.”

In 2017, Oxana’s son Sergey was arrested and convicted of trafficking as a dropper for an online shop called Don Diego when he was 18 years old.

It all began when Sergey wanted a new iPhone. All the other kids at school had one, and he didn’t. “He had a normal phone but it broke, and around that time we noticed he started slipping in his studies,” Oxana continued. “We punished him and gave him his grandad’s old phone until he straightened himself out.”

Turns out Sergey was doing a little more than flunking biology class. On the 26th June 2017 he was picked up with two friends trying to make a drop. It was just a day before his high school graduation, and Sergey managed to call his dad to say he wouldn’t be making it.

“We felt like such fools. We didn’t understand anything. It was scary,” Oxana recalled. “We were like blind kittens. We didn’t know what to do or where to run.”

Dropmen are charged under article 228 of the Russian criminal code (drug trafficking) and can get slapped with jail terms of up to 20 years, even for relatively small amounts. Sergey was first hit with a seven year sentence, then another court raised it to 13 years. His 18 year old friend also got 13 years and the third teenager, aged 17, got five years. Finally in January of this year, after nearly two years of appeals and taking her case to the media, Oxana and her family managed to bring it back down to six.

“Yes, everyone’s congratulating us—congratulations, your son got six years!” she said, her voice burning with sarcasm.

Life in “the Zone” (slang for prison) takes its toll on its young inmates. Like in America, convicts are used for cheap manual labour. Overpacked cells and non-existent healthcare is a great way to catch tuberculosis. Torture is common. For the younger inmates, spending time in the Zone will bring them closer to the prison subculture, and I don’t just mean singing along to jailhouse favorite Mikhail Krug’s 1998 hit ‘Vladimirsky Central’. The baby-faced new arrivals may come face-to-face with tattooed mobsters known as the vory-v-zakone (‘thieves-in-law’), or smaller cliques including murderous neo-Nazis and militant jihadis. In such illustrious company and with fewer options left on the outside, it’s no surprise that Russia’s recidivism rate is sky-high: more than four out of five inmates are frequent guests at the big house.

Oxana showed me a recent photo where Sergey looks skinny and pale. “He’s lost a lot of weight; he’s got dermatitis, and his vision is falling. He works six days a week sewing backpacks. The regime’s very strict but he keeps his head down, doesn’t get involved in anything. “So many of us! So much grief and tears!” Oxana cried. “How many girls and boys! They haven’t had time to finish school yet and they’re already in jail!”

Dropmen may be the ones getting locked up, but they’re expendable. New recruits can always be found.

RAMP and Hydra have revolutionized the Russian dope game. Whereas before you had to go to a Roma village, now everyone up to the wholesale level’s working online. The customer review system and testing service takes a lot of the swindlers and snake oil salesmen out of the picture—and it’s easier to avoid a police sting.

In January the MVD announced that a special unit would be formed to fight online drug trafficking. Whether or not they’ve got new tricks up their sleeve or keep doing more of the same remains to be seen. Last year, the government also passed a new “sovereign internet” law to (theoretically) cut Russia off from the global web in case of cyber-attack. It’s not clear what, if any, effect this will have on Tor and dark web activities, but it’s possible the drug menace will be wheeled out as an excuse to lock the internet down.

In the end, when the day comes to take down Hydra (and that day will come), it won’t be long before another site pops up and life goes on. In that sense it’s no different to any other drug cartel around the world. Did taking out Pablo Escobar lead to a drug-free Colombia? Hell no. That’s the thing about the Hydra: chop off one head, two more grow straight back.

Could Hydra be the future of drug dealing? “What is happening on Hydra shows that online drug markets will evolve according to the needs of their demographics and the quality of their infrastructure,” said Shortis. “The process of making a purchase is not quite as comfortable as sitting around and waiting for the postman. Customers must go out into a city or countryside and search for their purchase whilst avoiding raising the suspicions of the police or other members of the public. Some customers may also have to travel great distances just to find their delivery has been stolen by people who are savvy to where their local dropper is making deliveries, or that the police are actively patrolling the area where the drop has been made. While Hydra is very popular in Russia, it is rarely discussed in western cryptomarket forums.”

Before logging off, Galina left me with one last thought: “I’m just another person driven to the edge by high prices, low wages, and a lack of hope for the future. In the Middle Ages in Russia, ordinary people brought to despair went to the woods and became outlaws. Now, they are hiding on the dark web to become drug dealers.”

*Some names have been changed to protect identities