Federal judges don’t appreciate flimflam. That ought to trouble the National Football League. During an otherwise unremarkable Congressional roundtable discussion of concussions on Monday, league senior vice president of health and safety Jeff Miller made a remarkable admission: that a link exists between football and the neurodegenerative disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

“Mr. Miller, do you think there is a link between football and degenerative brain disorders like CTE?” asked Illinois Representative Jan Schakowsky.

Videos by VICE

“The answer to that question is certainly yes,” Miller said.

To anyone following medical science, this was hardly groundbreaking. Researchers have found CTE in 90 of the 94 brains of former NFL players that they’ve studied, and in 45 of 55 former college football players. The disease has only been found in people who have suffered brain trauma; the majority of those individuals played contact sports. Scientists believe other unknown risk factors play a role in CTE—not everyone who plays football develops the disease, just as not everyone who smokes ends up with lung cancer—but based on current evidence, brain injury appears to be the primary factor, and likely the necessary one.

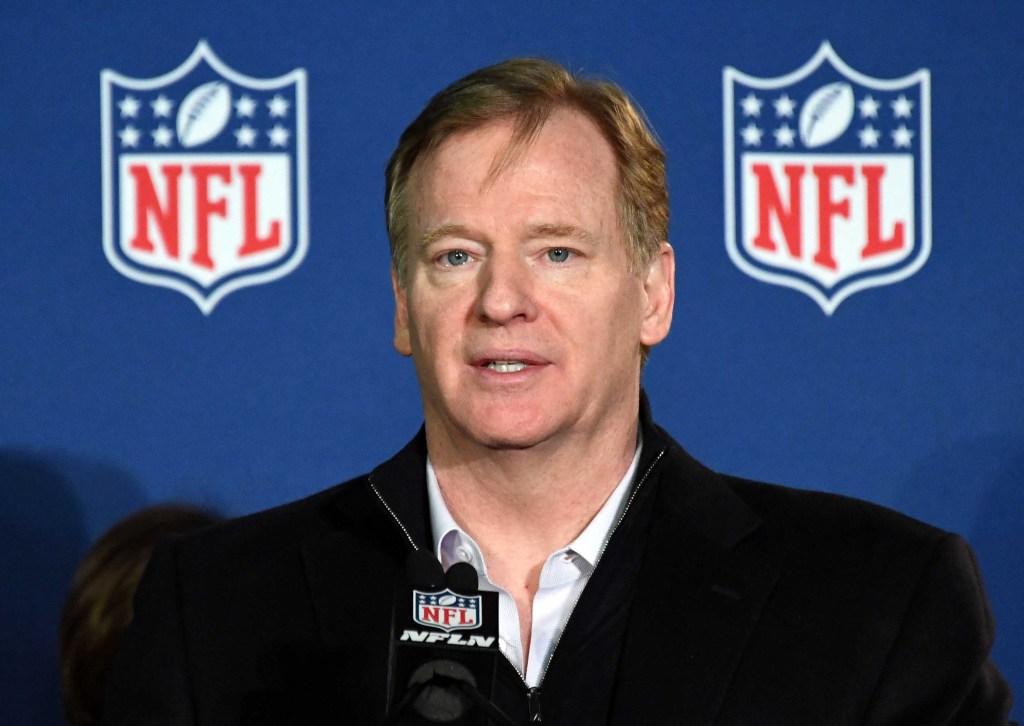

Of course, you wouldn’t know that from listening to the NFL. For more than a decade, the league has denied a connection between football and CTE, which has been found in the brains of Junior Seau, Dave Duerson, Ken Staber, Frank Gifford, Jovan Belcher and dozens of other former players. Three years ago, league commissioner Roger Goodell refused to acknowledge a link between his sport and brain injuries; before this year’s Super Bowl, NFL-affiliated neurosurgeon Mitch Berger told writer Bruce Arthur that there was “no” link between football and degenerative brain disorders.

Arthur also asked Miller the same question:

Why so shy? Money. If the NFL can successfully pretend its occupational disease doesn’t actually exist, then maybe it won’t have to pay for it. To wit: the NFL has been denying—and actively arguing against—a football-CTE link in federal court. Admitting to the link undermines the proposed multimillion-dollar settlement of a class action lawsuit brought by thousands of former players that accuses the league of covering up and lying about the brain damage risks inherent to football.

Currently being appealed by a group of retired players who object to its terms, the settlement largely eliminates compensation for CTE and its associated clinical symptoms. It figures to save the NFL hundreds of millions of dollars over the deal’s 65-year life span. But thanks to Miller, the league’s longstanding legal position now looks ridiculous. Actually, scratch that. Given that the NFL reportedly stands by Miller’s admission, it now looks mendacious. Downright Machiavellian. Which isn’t exactly out of character for an august, All-American institution whose greatest hits include League of Denial and all 243 pages of the Wells Report.

That probably should be a question mark, but good work nonetheless. Photo by @NYDNSports on Twitter

Initially announced in August 2013, the settlement basically works like this: in exchange for immunity from future lawsuits and never, ever having to reveal what it knew and when it knew it about brain damage—“tell the truth?” Nope!—the NFL will financially compensate ailing retirees. While the payouts themselves will almost certainly amount to pennies on the dollar—that is, given the high financial and emotional costs of living with a broken brain—former players suffering from Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and severe dementia symptoms will at least receive some actual cash.

As for CTE cases? No dice. Well, maybe a few rolls. But not too many. The families of players posthumously diagnosed with the disease between January 1, 2006 and April of last year could receive up to $4 million. But all subsequent cases—such as Stabler, Adrian Robinson and Tyler Sash, who were found to have CTE last fall and this winter—get nothing. Moreover, living retirees suffering from the life-altering mood and behavior disorders associated with the disease—including depression, explosive anger, impulsive behavior—get nothing, too.

Oh, and in case it isn’t clear, every past, present and future NFL player will forfeit the right to bring a class action suit against the league over CTE claims, all in exchange for bupkus.

If the above strikes you as odd, well, you’re not alone. Jason Luckasevic, the Pittsburgh-based lawyer who filed the first brain damage suits against the NFL, says that the settlement “began as a CTE case.” The league’s entire ongoing concussion crisis can be traced back to forensic pathologist Bennet Omalu’s groundbreaking 2002 discovery of the disease in the brain of deceased Hall of Fame center Mike Webster. Yet somehow, the NFL and the class action plaintiff’s lawyers who will receive over $100 million for negotiating the settlement managed to write CTE out of the agreement—a move akin to writing mesothelioma out of an asbestos case, and one that Kansas City-based brain injury lawyer Paul Anderson calculates has already kept roughly $8.4 million in the pockets of league owners and their insurers.

Unsurprisingly, about 90 retired players are appealing the deal. Arguing that that the link between CTE and football-induced brain injuries is well-established—at least as solid as the link between the sport and the other diseases the settlement compensates—they insist that the deal should do more. It should:

1. Compensate future cases of CTE diagnosed after death.

2. Test and pay for the mood and behavioral symptoms associated with the disease that tend to afflict individuals at younger ages, and not just the cognitive symptoms that tend to begin later in life

3. Accommodate the future development of tests to detect CTE in living brains, something most researchers think is less than a decade away.

In response, the NFL has maintained that CTE deserves to be left out of the settlement because “researchers have not reliably determined which events make a person more likely to develop” the disease and that “the speculation that repeated concussion or subconcussive impacts cause CTE remains unproven.” (Never mind that the same can be argued about Parkinson’s, ALS, Alzheimer’s and dementia). During oral arguments before a federal appellate panel, NFL attorney Paul Clement stated that science was “years and years” away from proving a causal link between brain trauma and the disease. In an affidavit filed in support of the settlement, University of California, San Francisco researcher Kristine Yaffe stated that mood and behavior disorders have many risk factors and can be unrelated to CTE, which isn’t the same as insisting they can’t come from the brain damage characteristic of CTE, but whatever.

In short, the NFL has spent two decades going from former commissioner Paul Tagliabue’s insistence that brain trauma in football is a “pack journalism issue” and demanding that Omalu’s findings be retracted from a scientific journal to telling federal courts that yeah, well, maybe CTE is really a thing, but who knows what causes it, or what it does to someone, and it’s probably just a big coincidence that so many former football players have both the disease and the same symptoms, and an even bigger coincidence that CTE has never been found in someone who didn’t experience brain trauma. Is that progress? Does it begin to address the families of men like Robinson, a league journeyman who hanged himself at age 25? Or is it more of the same from an organization whose doubt-manufacturing playbook has shifted from Big Tobacco-style outright denial to fossil fuel industry-style teach-the-controversy, and whose public face, Goodell, recently compared the risks of playing football to the “risk in sitting on the couch?“

TFW you’re the only man standing between America and the coming couch-pocalypse. Photo by Matthew Emmons-USA TODAY Sports

Back to Miller’s unexpected flip-flop. It calls into question the NFL’s entire position—has the league been bullshitting all this time?—and comes at a fortuitous moment. Last spring, federal judge Anita Brody approved the settlement, essentially taking the NFL at its word. The deal is now before appellate judges. They are hardly obligated to follow suit. On Tuesday, player lawyer Steven Molo flied a letter to the court asking that the judges consider Miller’s statement, which “cannot be reconciled with the NFL’s position in briefing.”

“The NFL’s statements make clear that the NFL now accepts what science already knows: a ‘direct link’ exists between traumatic brain injury and CTE,” Molo wrote. “Given that, the settlement’s failure to compensate present and future CTE is inexcusable.”

Echoing Molo’s logic, sports attorney Daniel Wallach told USA Today that that Miller’s admission “could change everything” with regard to the settlement. Will it? If you accept that football and CTE are linked—the way football and the other brain disorders covered by the settlement are linked—then players diagnosed with the disease and its symptoms should be compensated. Otherwise, they should be released from the deal and allowed to sue the NFL en masse. Anything less would be unjust—a final affront to the families of Seau and so many others, and a high-priced mockery of both medical science and American jurisprudence.

During a fairness hearing for the settlement held in Philadelphia in 2014, Brody had a verbal slip-up of her own, at one point asking a plaintiff’s lawyer what’s TBI?—never mind that TBI is short for traumatic brain injury, the very essence of the case. Brody is 80 years old. Perhaps it was a senior moment. Or perhaps it was a window into how the NFL was able to bamboozle her. Federal judges are legal geniuses, not medical experts; they rely on the evidence and information put in front of them, an issue-framing process the league’s white-shoe lawyers have skillfully manipulated. (See also: Deflategate, Exponent, the aforementioned Wells Report). Thing is, the appellate judges no longer have the same excuse. Not after Miller made the mistake of telling Congress the truth. With the settlement still undecided, the old adage applies. Fool the courts once, shame on the NFL; fool them twice, and there will be plenty of shame to go around.