Welcome to Waypoint’s End of Year celebration! This year, we’re digging deep into our favorite games with dedicated podcasts, interviewing each other about our personal top 10 lists, and reflecting on the year with essays from the staff and some of our favorite freelance contributors. Check out the entire package right here!

Chess might be sick. It’s hard to tell. “Draw epidemic continues as grandmasters play safe at Grand Tour” reads the headline to a Guardian story about the second time in the past few months that top level chess competition was brought into the (once rare) tiebreaking stage.

Videos by VICE

The first time was when current world champion Magnus Carlsen decisively secured a win over challenger Fabiano Caruana, but only after three weeks of draws and a tiebreaker played out in “rapid chess,” a format that Caruana was less experienced in. Some of those draws were hard fought, but others (including the final match in the regular set) were the result of weak nerves, at least if you believe former world champion (and conspiracy theorist) Garry Kasparov, who was shocked when Carlsen offered Caruana a draw despite having a decidedly stronger position in the match.

While some fans have extended Kasparov’s analysis of one particular game into an accusation of cowardice among pro players of “classic chess,” others have argued that it is the current culture (and ruleset) of chess that leads to these results. Between the rise of computerized chess engines, the limited number of games played in finals matches (encouraging conservative play), and a lax play schedule (allowing players a lot of rest and preparation between matches), the result is a tightly controlled board, with few mistakes and even fewer dramatic plays.

It’s worth saying that some in the scene think that things are fine, pointing to the quality of many great matches in the slew of ties. But it’s hard not to be sympathetic when someone like Zach Young, producer of The Intercept’s Deconstructed podcast and chess blogger for HuffPo described the trend as “poisonous” to chess-as-spectator-sport. “Shorten the games”, he tweeted, “Switch to chess960 [a system that randomizes starting board position]. Fill the playing hall with wild animals. Anything to stop the draws.”

Young’s words startled me when I read them, because they reminded me of someone else’s. When prodded to explain why, in an accelerationist turn, he said he was hopeful after Trump’s win in 2016, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek told VICE News that “the inertia of status quo should somehow be broken and open space for a new political reconfiguration.” Fill the playing hall with wild animals.

…unlike in chess, in politics and life draws are often lived as losses.

If I was disgusted by Žižek’s remarks at the time, it was not because I thought that the left shouldn’t respond to Trump’s election by turning it into a catalyzing event. It was because the ease with which he said the words reflected a fundamentally disinterested and safe position. (As does Zach Young’s, for that matter—it’s probably easier to demand shorter games when you’re not the one on the clock).

At the time of publishing this, we are midway through day 10 of the US government shutdown. We’re also a decade or so into an era of congressional dysfunction, where gridlock-as-strategy has begun to deprecate the government. This is not to say that there have not been any legislative or political victories, but that in aggregate, the entire we seem stuck in a cycle of forced draws—starting with a long period in the early Obama presidency when the dominant Democratic party refused to play aggressively, eventually losing control to a powerful right-wing movement determined to do even less. And unlike in chess, in politics and life draws are often lived as losses.

Is it any wonder that in 2018, I’ve found myself consumed by turn-based tactics games more than any others?

For the bulk of my life, tactics games were just fun. Unlike the Elder Scrolls or Grand Theft Autos, which seemed to invite critical prodding, tactics games were rarely objects of inquiry when I was a young player. I obviously knew that my hours spent tinkering with job classes Final Fantasy Tactics was more relaxed than the those spent permanently losing soldiers in X-COM UFO Defense. But I wasn’t asking questions about what types of conflict those games were modeling or what type of heroic fantasy they were offering me.

But this year, I couldn’t stop that line of thinking. I found myself taking them apart in my mind, figuring out how these games played with empowerment and disempowerment, trying to piece together their (often unspoken) rules of engagement. Unsurprisingly, I also spent a lot of time thinking about out how each of them disincentivized inaction, encouraging players to break through stagnation draw games.

Into the Breach jumpstarted this interest for me when it released back in February.

Before it launched, Waypoint’s Rob Zacny and I had launched what would become a year-long XCOM 2: War of the Chosen campaign, and even just a dozen or so hours into that game, we’d hit our quota of familiar tactical tropes: beloved customized characters, long term plans moving at an extremely slow rate, and the curse of a near-perfect accuracy shot going wide due to bad luck. Into the Breach had damned near none of that.

Instead, Subset Games’ follow-up to FTL was a crystal clear tactical puzzle. In place of procgen characters and expansive research trees, Into the Breach offered the clarity of a board game and the short, replayable sessions of a roguelike.

I wrote in my review that its take on transparency and movement-based combat transformed player into choreographer. And in doing so, it made me less interested in getting traditional tactics wins. Into the Breach isn’t about “clearing the board” of enemies. It’s about protecting certain tiles on the map (and the innocent people there-in). How do you break a draw in a game like Into the Breach, where “winning” often looks like a draw? Attrition.

Get good enough at the basics that you can keep the kaiju from doing damage, outlast them for long enough, and eventually a grand opportunity will be revealed for real success. If ItB were to give you advice on how to break through gridlock, it would tell you to lean on proceduralism and politicking to maintain the status quo until you have enough momentum and confidence to shift things your way

(Then, you know, dive into a volcano with your mechs. Easy.)

When a friend of mine first tweeted about “agadmator,” a YouTube channel dedicated to analyzing interesting chess matches, I thought maybe I’d watch five minutes before getting on with my day. I hadn’t really played chess since junior high, but she wrote that his videos reminded her of Jon Bois’ work explaining sports, in that they make something she knew little about engaging, which sounded great. And you know, with a video title like “Anna Rudolf Accused of Cheating with an Engine Hidden in her Lip Balm!”, how was I not going to at least click play.

So, I watched the video. The whole video. I don’t mean that the whole 22 minutes played, either. I mean that I watched it. I didn’t check Twitter, or my email, or either of my work chats. I didn’t pause it seven times to investigate some new distraction or to focus on a game I was playing. It totally consumed my attention.

Partly, I think that’s because “agadmator’s Chess Channel” is remarkably, charmingly straightforward. “Hello everyone – This is a chess channel :)” reads the description on the about page, and that attitude is carried into the videos, where his warm greetings lead into turn-by-turn analysis which even a neophyte like me can follow, so long as I’m paying attention.

And that the part that I think actually made me watch. Despite agadmator’s geniality, these videos make a demand on my attention. Unlike a PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds stream or part 17 of a 40 part Resident Evil 2 Let’s Play or a procedural crime show on USA, I can’t kind of watch agadmator’s videos with a sort of flightiness, focusing only for moments of high drama or tension. Which isn’t to say that there aren’t people for whom those other things do demand attention, but after years of watching that sort of content, I’ve learned that constant engagement with them isn’t rewarded.

But with agadmator, it always is. And in 2018, a sleepless year that often left me feeling directionless, disinterested, stifled, and struggling with a spike in my long running depression, the ability of something to draw my focus this clearly was more than just a nice thing to have. These videos—and the tactics games that I was playing when I wasn’t watching them—weren’t just “demanding” my attention, they were rebuilding it.

Months after Into the Breach, Valkyria Chronicles 4 went hard in the opposite direction. Sega’s latest entry in their anime-styled take on World War was in some ways just more of the same for series: A collection of beautiful battlefields with a limited number of possible successful strategies, and a collection of charming soldiers to execute on those plans. Sure, you may lean on your sniper more than another player, or might take a particularly headstrong assault with your (honestly, overpowered) scouts, but most maps have a core solution with a few variations.

Which doesn’t mean that the game isn’t effective at making you feel like a brilliant tactician.

Take the Battle of Siegval, a multi-part fight that serves as the first act’s finale and is probably my favorite run of missions in the entire series, largely because it delivers on feelings of scale and chaos that the series has never been able to communicate until now. You’re part of a huge offensive, meant to punch a hole through the evil Empire’s greatest fortress. The initial push is across a massive, open field, and requires you to carefully pace your advance alongside an allied tank unit. Break through that line, and you’ll wind up in a winding mountain pass, where you’ll need to use small pathways and ladders only accessible to your infantry to win. And eventually, one of the game’s first true challenges requires you to split your team in an effective way to rescue a team member pinned down across a fragmented map.

Where Into the Breach let me become a dynamic, master tactician, Valkyria Chronicles 4 encouraged me to be a daring commander in search of the perfect solution. And because those solutions are always the most dramatic sort, the game seems to prize gutsy heroism instead of flexibility. Identifying each of those solutions made me feel brilliant in the moment, but with some remove it’s hard not to recognize how badly these battles want to be won. Which would bother me if I didn’t kind of love it so much.

As I discussed with Rob Zacny and Kotaku’s Heather Alexandra a few months ago, this fantasy of victory is drawing on decades of genre history. VC4 understands it doesn’t need you to be a great general to make you feel like Legend of the Galactic Heroes’ Yang Wen-li. It just needs memorable props, unique strategic premises, and a lovable group of supporting characters. Well, mostly lovable. An early scene that features one of your comrades sexually harassing another one is framed as pure comedy, and then dropped without a second thought. Ugh.

And that is in many ways the problem with VC4’s idea of how to break through the draw game. Heroism has its place in our narratives, but is it a reliable strategy? Certainly, big dramatic actions have pushed through congressional gridlock or led to a necessary shakeup in a stagnant relationship. But heroism requires placing complete trust in fallible individuals, and dramatic success relies on the sort of Hollywood logic that rarely appears in real life.

As agadmator walks you step by step through a match, he’ll occasionally pause to offer context for the maneuvers being played. The board opens up to reveal a sense of history, and because there is a sense of history there is also a sense of the future. Oh, the king’s gambit was in fashion once? I wonder if one day someone will find a way to make it relevant again. (Never mind that I barely know what a king’s gambit is.)

Other times, he’ll slow down his analysis and walk the viewer through multiple possible pathways, always anticipating my questions. Why shouldn’t this player capture that bishop with their knight? And in sixty seconds, agadmator will have shown me exactly why that’s the case.

Despite their relaxed energy—in some entries, the host’s dog lounges on a couch in the background—these videos tend to build to two potential climaxes (and sometimes to both). The most common is that agadmator will come to the key moment in the match and then invite you to speculate about the next move. “And now, feel free to pause the video here,” he’ll say, adding a quick clue about why the player made the move they did. And as in any of my favorite tactics games from this year, getting the answer right makes me feel like some sort of chess genius. (I am extremely not any sort of chess genius).

The second possible climax to certain agadmator videos is saved for chess maneuvers that, you can tell, agadmator particularly admires. After setting up the context of the match, exploring all of the different branches of possible play, and giving the viewer a chance to flex their minds, he’ll use this phrase I just cannot shake: “And then he got this Idea.”

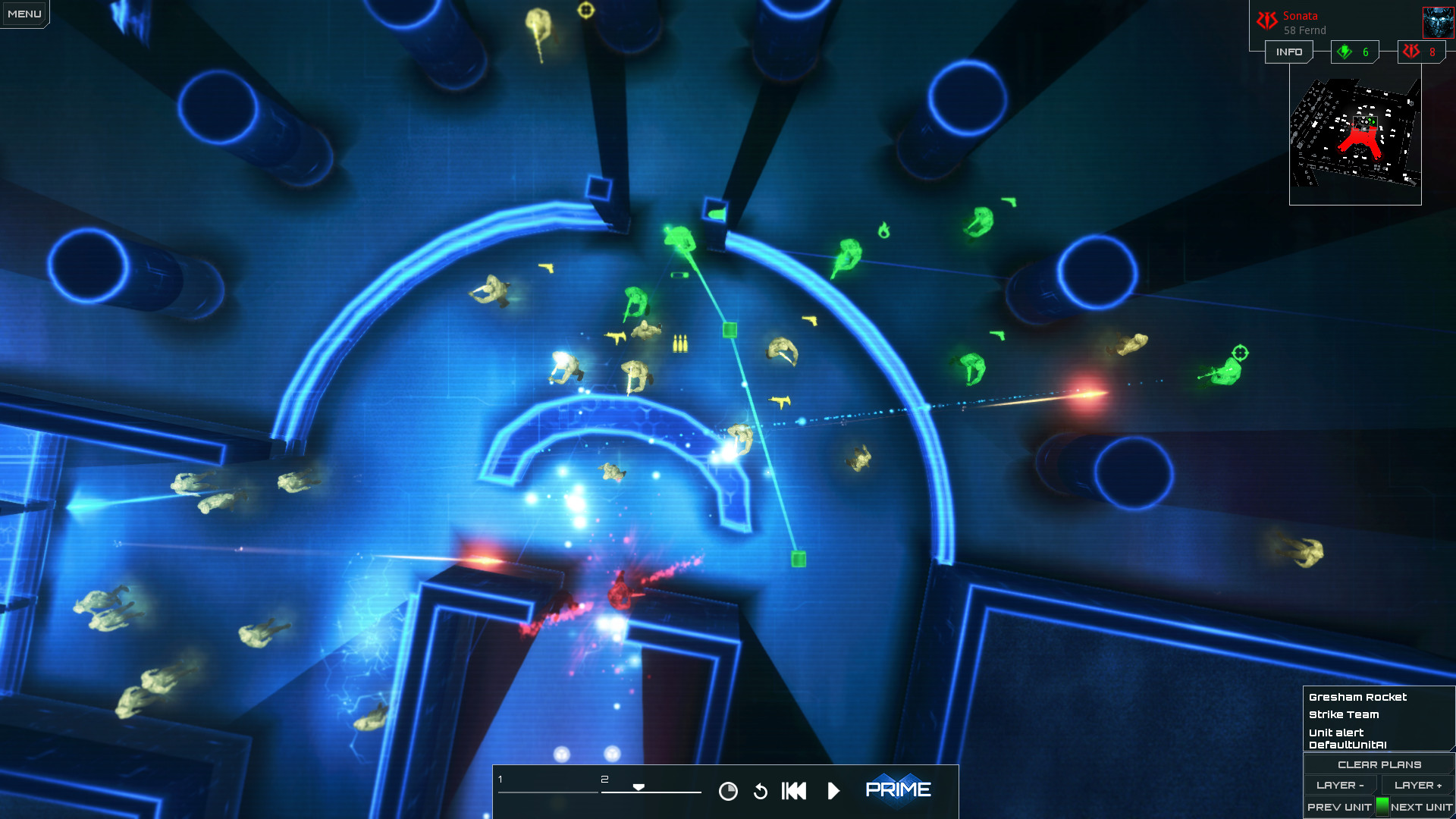

Frozen Synapse 2, which I played alongside VC4 back in September, felt like it was designed explicitly to undercut ideas of individualistic heroism in favor of something more compromised and prosaic. Set in a futuristic, procgen city, you play as a group not unlike XCOM’s titular team, dedicated to identifying and stopping a seemingly extradimensional threat. But you quickly realize that bureaucracy and budgets are your real foes.

As I wrote about ahead of its release, Frozen Synapse 2 problematizes the concept of the extralegal military force that is at the heart of so many tactics games. XCOM is a unit of alien killing badasses whose only job is to be a group of, well, alien killing badasses. Sure, France might get mad at you if you don’t save Paris from a flying saucer, but they’re not going to ask you to stand guard at the Arc de Triomphe or to take shots at their political enemies. XCOM isn’t just extralegal, its extrapolitical.

But FS2 rejects the idea that you could give someone the legal authority to kill and still manage to leave politics out of it. You immediately find yourself being asked to do favors by the politicians who run the city’s various districts. And when you refuse, they cut your funding. But do those favors and you risk alienating (or angering) the corporations, collectives, and AI constructs that live in the city, each of which is competing with you over a near-magical resource. If any one faction successfully monopolizes it, the game is over.

Because of this interlocking factionalism, Frozen Synapse 2’s vision of tiebreaking is in some ways the most darkly rendered. Like a Vox explainer, FS2 imagines that victory comes to the side with the most information. After plotting out your moves—and guessing at your foe’s—you lock in your turn and wait for the mission screen to play it back for you, because in FS2 both you and your enemy’s soldiers move at the same time.

Though the city and its characters are simple figures of blue and red, the game’s portrayal of violence is stark and sudden in a way that it isn’t even in the more detailed games on this list. Loud, scattered gunfire leads to the cold voice of an AI accounting the piling up of deaths. You rewind and hit play again, each time making more and more sense of whatever chaos exploded on the screen a moment ago.

There are winners and losers in every Frozen Synapse 2 firefight. There is no such thing as a draw, and anyone who tells you otherwise is either winning or trying to trick you into forfeiting.

There are so many more tactics games that intrigued me this year too, and each said something about conflict and victory: BattleTech, which has an economic model that makes many wins feel like losses (and which you can hear me praise effusively on the podcast last week ). All Walls Must Fall casts you as a technoir mercenary in an alt-future cold war Berlin, and draws on that city’s history with queer nightclubs not only as set-dressing, but as key influence into a combat system all about time and rhythm. Phantom Doctrine sticks with the cold war theme, transports you back to 60s, and totally does away with to-hit chance—secret agents just don’t miss, and you better figure out how to win anyway. Mutant Year Zero teaches you to skew any battle your way before you even engage, and Bad Northis all about preparation.

The list goes on and on. And maybe it was because of all of this high concept complexity that I found myself fascinated by chess for the first time in decades.

Chess was the first “tactics game” I ever loved. Taught to me by my dad as soon as I was old enough to hold its varying moving pieces together in my mind. I took to it immediately—and I don’t mean that I was good, I mean that I was fond of it. By fourth grade I’d complain whenever someone wanted to play checkers instead, and offer to teach them Chess instead. I would play the game during recess on rainy days, before class started if I got in early enough, and during the after-school program that served as a place to stick kids whose parents couldn’t pick them up at 2:30.

But by the time I got to junior high, I began to fall off the game, beyond the occasional dip into online chess or playing a bad PC version of the game on my dad’s work computer while he was busy elsewhere. I still played the occasional game, but I was frustrated by my own lack of skill.

I’d never been good. I just understood the game more than the people I’d played with. It wasn’t that I was “three moves ahead,” but against the other kids, planning even small plays meant that I was operating at a higher level. By seventh or eighth grade, that wasn’t enough. I’d still take pieces, but had no sense for pace or strategy. And I absolutely never, ever “got an idea.”

When agadmator says that some grandmaster or young prodigy “gets an idea,” the tenor of the video changes. What follows tends to be some clever ploy—more Valkyria Chronicles 4 in narrative energy than Into the Breach—that turns the match around or ends the opposing player’s resistance. It slipped into my tactics lexicon immediately. Catch me streaming XCOM 2 and announcing to my Rob, my co-host, that I’ve “had an Idea,” and you can hear the capital I in my pronunciation.

When I was a kid playing chess, I thought the way you won was by taking pieces.

It was an infectious way of thinking about chess, or about conflict in general. Find the weakness in the armor, the unpredictable punch they won’t see coming, the never-before-said phrase, and you’ll win. In politics, career, and personal life this year, I’ve come to find myself navigating draws, dead ends, and general stagnation. It is so tempting to believe in a world where finding an Idea is all you need to get by.

But these chess masters don’t win just because they’ve had capital-I Ideas. In fact, the only reason they are able to have Ideas in the first place is because of all of those other sweet-sounding chess jargon that agadmator uses: Activated rooks. Developed bishops. Strong pawn structure.

And when I first thought about this essay back in September, I planned on wrapping it up right here: When I was a kid playing chess, I thought the way you won was by taking pieces. Now, as an adult, I know that it’s about developing the board. It’s time that we stop thinking about pawns and start thinking about pawn structure. Stop aiming for immediate gain, and instead extend our control of the board, spreading our pieces out or focusing them like a fist. Ideas are worthless without the foundational work beneath them. Do the work so that one day you can make the big play.

It’s a really easy outro to write. Underscore the parallel between a well-developed chess board and healthy civil institutions. Explain that we need to be more Into the Breach, less Valkyria Chronicles, more dynamic, less heroic. Quote Heidegger (“The only possibility available to us is that by thinking and poetizing we prepare a readiness for the appearance of a god, or for the absence of a god in [our] decline”), and issue some call to action about preparedness. Maybe include some echo of agadmator’s fun “pause the video here and try to come up with your own solution.” Call it a day.

And you know, pretend I did all that, because I think I do agree with it.

But writing those words hasn’t helped me get out from under that Guardian headline: “Draw epidemic continues as grandmasters play safe at Grand Tour.” The best players in the world, with all the technology and data and rest they need, and they’re playing boring, safe games that increasingly bore people. Drawing again and again, until they have to play a different version of chess to decide who is really the winner. Fuck, man.

So I went back through my notes, scrolled through my screenshots, and watched more videos. In search of a more honest conclusion, I kept coming back to Frozen Synapse 2, but I couldn’t tell why at first. It’s a good game—it made my top 10, even—but it’s by far not my favorite of the year. It’s messy, a little buggy, and not particularly clear. I’ve had some truly standout encounters—including one rolling battle that I broke down in length about at about 1:08:00 on this episode of the podcast. But those weren’t what was bringing me back to it either.

I eventually realized that what seemed true about Frozen Synapse 2 was the way the game balanced two ideas: First, that life was inherently shot through with compromise and entanglement. Second, that conflict also fundamentally had winners and losers. Even if getting into a firefight on some representative’s property meant I lost some budget, I still won the fight. Even if Magnus Carlsen was forced into a tiebreaker, he still won, right?

And, hey, wait a second. Was Carlsen forced into a tiebreaker? Kasparov’s entire argument was that Carlsen had a stronger position than Caruana, his opponent, and could have confidently pushed for the win in the final regulation match. And yet, Carlsen offered Caruana the draw in that game. Why? Perhaps, as some speculate, because Carlsen knew that his chances for a win were that much greater in the rapid chess tiebreaker matches, because he had much more experience in that faster mode of play than Caruana did. (For those who care more about fighting games than chess, compare it to SonicFox’s “side switch” during Evo 2018.)

Maybe that’s the tactical (well, strategic) takeaway I’m looking for heading into 2019. For those of us committed to making the world more compassionate, egalitarian, and just, it’s time to broaden our focus. Yes, in any conflict, we need to prize the developed board over the taken piece. But we must remember also that we are also playing a metagame at all times. That means that losses, setbacks, and mistakes are due to happen, and we have to roll with and learn from them. More importantly, it means that we need to be willing to recognize and shift the rules of engagement.

In 2019, let’s take as a starting point that every conflict we wind up has a metagame, and that the rules of that metagame are often stacked against us. In politics, that’s the state of the filibuster rule but it’s also ongoing calls for “civility.” In the lives of marginalized people, when laws protect those who do us harm, it has meant learning how to show deference to the forces of injustice. For workers, these rules ensure lower income than we deserve and precarity in our careers: As SCOTUS ruled in the case of forced arbitration this year, workers are just individuals. That makes us easily replaceable, and less able to legally hold our employers accountable.

These rules—like so many others—are fucked. And we should change them, or at least learn how to play the entire metagame instead of treating each conflict like it exists in a vacuum.

What does that mean? For Magnus Carlsen, it was pushing the game to a tie-breaker, where the rules were more in his favor. For SonicFox, it was using arcane procedurality to switch to a more comfortable side of the screen (and freeze out his opponent in the process). And frankly, for well over a decade now, the Republican party’s playbook has been built entirely around obstructionism (which is partially why they struggled to enact policy after 2016).

For us, this should mean being loud, getting organized, and supporting large scale changes instead of small victories. In the world of environmental justice (and you know, wanting to survive climate change), it means that we should be pushing for a Green New Deal instead of playing inside of the acceptable lines of incrementalism like we normally do. In our workplaces, we should continue to organize so that we can engage our employers with the leveraging power of collectivity to make our workplaces safer, our paychecks fairer, and our stress levels lower.

So, let’s not go into 2019 thinking of it as a blank slate or a fresh start.

And (a maybe surprising side effect here) I think it means that we need to be more compassionate with each other in this fight, too. Playing the metagame means evaluating each other holistically, identifying trends of behavior instead of individual actions, and recognizing the opportunity for future efforts. This does not mean that we should not be aggressive in our attacks on injustice, or that we should forgive and forget when someone has truly done harm. But it does mean widening our scope of analysis, and offering corrective rather than expulsive criticism. (That, of course, rests on all of our ability to “take the L,” accept that we’ve made mistakes, and choose to learn from good faith criticism instead of shutting it out).

So, let’s not go into 2019 thinking of it as a blank slate or a fresh start. It’s neither. As the clock ticks on climate change, as we march closer to primary season (ugh), and as everyday seemingly brings a new reason to doubt the platforms and social structures that we’re tied to, it is increasingly clear that we cannot escape the past’s ability to delimit the possibilities of our present and future. So, in 2019 let’s commit to looking at the big picture. Taking pieces helps, developing the board is good, but to win the future, we need to be remember that tomorrow isn’t a whole new game, it’s just one more match in the series.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Sony Interactive Entertainment -

Screenshot: The Game Awards -

Screenshot: EA Sports BIG -

Screenshot: 2K