A shot-up Vladimir Lenin statue in Debaltseve, in eastern Ukraine. All photos by the author

A golden, faceless Vladimir Lenin statute glistened in the sun. The Ukrainian Army had shot up the statue for target practice during their time in this eastern city, called Debaltseve, which is now occupied by pro-Russia separatists under the auspices of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR). The head of another Lenin lay in a patch of sunlight inside what was once a theater in the city’s House of Culture.

You can trace the path of the retreating Ukrainian Army by the trail of destroyed Lenins in their wake. The metal ones, I was told by DPR forces, were being melted down and turned into bombs by their enemies.

Videos by VICE

I flew into Ukraine’s capital of Kiev in late April, and after a Kafka-esque paperwork nightmare, crossed the frontline between the Western-aligned central government and the self-declared DPR. War had broken out over a year earlier, but according to a couple of Russian journalists I spoke to, only since the previous month had the Ukrainian government started issuing exit stamps at the last checkpoint before no man’s land—a tacit acknowledgment it had lost control of the territory.

I checked in at the mostly empty Donetsk Ramada, its windows crisscrossed with tape. Prices had plummeted, but caviar was still on the room service menu. The place seemed to be serving primarily as a hangout for the Night Wolves, a biker gang led by a mysterious former doctor known as “The Surgeon.” They appeared to be escorting Ukrainian pop stars around the DPR, perhaps at the behest of the local government. Concerts were hurriedly arranged in town squares as part of some kind of morale-boosting exercise.

The next day’s drive from Donetsk to Debaltseve took my translator and I alongside the frontline. We passed toppled electrical masts, blown bridges, and burned out vehicles before arriving in the city of Vuhlehirsk. DPR troops were still clearing the place of mines, and we toured a damaged tram depot, which was strewn with nail-like anti-personnel shrapnel that our escorts claimed violated the Geneva Conventions.

“It falls like metal rain,” one soldier recalled of the shrapnel. “Doctors cannot find it in the body. If you survive, you will have much trouble getting through airport security.”

In Debaltseve, the city’s commander arranged a tour. Our leader was an officer known to us only as Spartag. He liked to speak in the third person.

“Step only where Spartag steps,” he shouted over his shoulder.

Spartag strolled up a dirt path, bordered by concrete animals, leading to what used to be the Salute Children’s Camp. More recently, it had been commandeered by the Ukrainian Army. They booby trapped the place as they retreated, DPR soldiers told me as we wound our way through a half-cleared minefield to the “Childrens’ Disco”—a brightly-painted concrete pavilion that recently served as a munitions dump. As DPR forces had advanced on the camp, situated on the outskirts of Debaltseve, a shell had hit the munitions dump and blown a fireball through the dancehall, clearing it out completely.

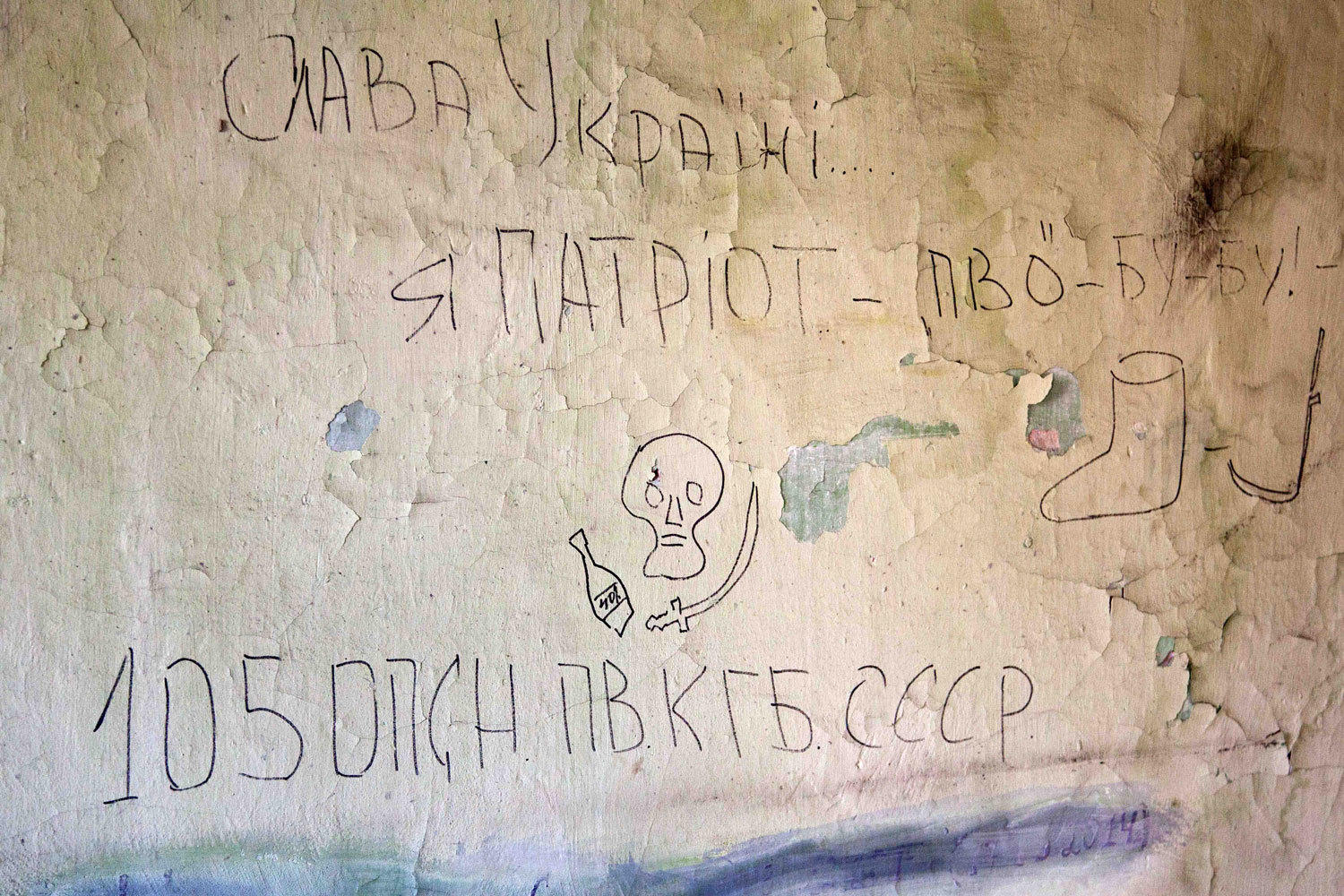

As we picked through the rubble, I found a photograph of the Ukrainians posing with flags in the exact same location a few months prior. It had been Klitschko’s battalion, the DPR soldiers told me, referring to the Heavy Weight Boxing Champion of the World who briefly ran for president during last year’s political unrest. Like the children who had long-since fled, the Ukrainian troops had left the camp full of personal effects and graffiti.

On the door of a makeshift barracks someone had scrawled: Beware! There are evil soldiers in this room and one benevolent corporal.

A bullet-riddled helmet read: Putin is a bitch.

A pamphlet in a room full of bibles promised: If you die, you will go to heaven.

A wall of mostly blue and yellow children’s crayon drawings fluttered in the breeze. The room had not yet been cleared of booby-traps, so I could only look through the window. Kids had drawn tanks and men with guns. The bullets came out as dotted lines. A DPR soldier snatched a drawing that had blown away from the ground, reading it with a grin: I’m proud of you, Ukrainian soldier.

“This doesn’t look like a child’s handwriting,” he sneered as he tossed it onto a pile of empty vodka bottles.”You see how much they drink?” he added.

The soldier stopped for a moment to free a drowning honey bee from a cup of rainwater before proceeding to clean his boots with an abandoned Ukrainian flag.

Spartag led us out back to the abandoned Ukrainian Army trenches. We crawled with flashlights down into deep earthen bunkers housing stoves made out of abandoned oil drums. There was a discarded Aspergillum that had been used by a priest to bless the troops with holy water. There were rolls of yellow tape that the irregularly dressed soldiers had used as armbands to differentiate sides during the fighting. (The DPR’s armbands are white.)

We walked single file through another field until we reached a bridge. On the far side was the Children’s Village, marked by a tall, conical tower that seemed to come straight out of a fairy tale. Spartag claimed that the Ukrainian Army had used the tower as a sniping platform—picking off anyone who came by to draw water from the river.

“End of tour,” he announced unceremoniously.

Check out VICE News’ Russian Roulette series on the conflict in Ukraine

We headed back to the bridge, where the DPR troops held a spontaneous target practice. Everyone aimed for a stick jutting up out of a nearby lake. The man next to me playfully handed me his AK-74.

“You shoot too,” he encouraged.

He smiled and suggested that I join their ranks.

“We have many foreign fighters,” he boasted. “There are French and Canadian, many Europeans. Anyone can join us. You just go to the office with your documents and they check your health. If you’re healthy, they’ll give you a uniform. You don’t even have to speak Russian.”

Follow Roc’s project collecting dreams from around the globe at World Dream Atlas.

Head of a decapitated Lenin statue

Entrance to the children’s camp

Ruins of the House of Culture in Debaltseve

The patriotic drawings of children

Children’s anti-war drawings

A bullet-riddled helmet and discarded religous books

Insignia of the Ukrainian battalion formerly stationed at the children’s camp

Anti-personnel projectiles

Abandoned makeshift barracks at the children’s camp

Discarded aspergillum

The children’s disco

Destroyed electrical mast on the road to Debaltseve

DPR soldiers pass the ruins of the Debaltseve House of Culture

Deserted Ukrainian trenches at the children’s camp

Discarded religious material

Discarded gas mask

DPR soldier cleaning boots with the Ukrainian flag

Abandoned Ukrainian trenches

Child’s drawing of a tank

The Children’s Village

The Children’s Village with sniper tower in the foreground

Graffiti from the Ukrainian battalion

Concrete animals at the Children’s Camp