Before the judge enters the overflowing courtroom in a strip mall in Burlington, Ontario one recent morning, a court staffer stands up at the front and motions her hands for everyone to stay seated.

“This is really informal,” she says. “There’s no need to rise here.”

Videos by VICE

One man in the audience looks at his watch and whispers he’s nervous for his upcoming appearance. Another man, holding court documents and wearing a construction outfit, reaches for a crying baby being held by a woman next to him.

It’s the one day this month the special drug treatment court will convene to hear from Ontarians facing drug charges. Here, people get second, third, and fourth chances, but they need to commit to a strict recovery regimen that includes regular urine tests, check-ins, and intense therapy sessions — they call it ‘the program.’ It’s one of the only courts of its kind in Canada to adopt the unorthodox approach.

But this year, in the midst of a raging opioid crisis that has claimed thousands of lives, the landscape around addiction has shifted. With law enforcement vowing to get even tougher on drug crimes, advocates are pointing to drug courts such as these as an overlooked solution. At the same time, there’s concerns over whether these types of courts provide an easy out for alleged drug criminals who are just trying to avoid prison.

VICE News spent a day in November at the Burlington court, as a parade of drug offenders appeared and disappeared before Justice Stephen Brown, their varying degrees of progress on display.

This is Justice Brown’s brainchild. Years ago, one of his family members struggled with addiction and was arrested, but no court like this existed. He had to get rehabilitated on his own, and that experience led the judge to turn his mind to legal alternatives. “Welcome to drug treatment court,” Justice Brown, a soft spoken man with white hair and a white beard, told every person who stood before him.

This day in November begins differently than most. Court support worker Megan McNeil has brought some graduates of the program back in for the first time to share their experiences with those going through it now. “A reunion of sorts,” she adds, before motioning them up to the front.

Agatha Kozakiewicz is a recovering alcoholic who was admitted to the court last year for shoplifting. She loved her time in the program so much that she put off graduating as long as possible.

“Everyone here is tremendous, even the one bad guy,” she said with a thick eastern European accent pointing her finger at the Crown prosecutor, Sean Bradley. Everyone laughs, including him.

“And this judge is way better than Judge Judy,” Kozakiewicz exclaimed. She’s since stopped drinking and regularly attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. “We all need time to heal, and you’re going to get healed 100 percent after this, you’ll be good to go,” she said.

“The current criminal justice system is flawed and people get misguided in it.”

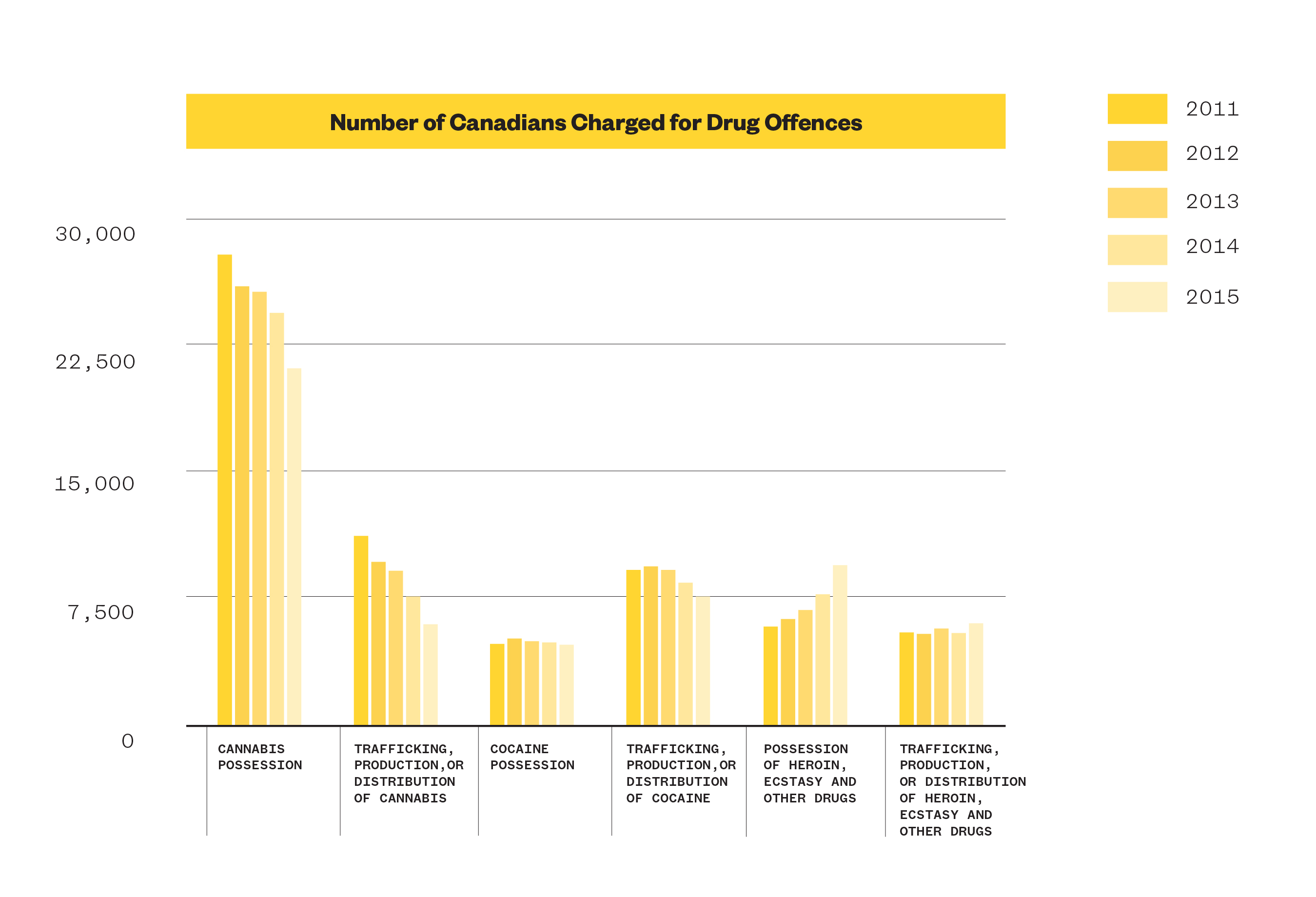

The rate of drug offences reported by police is declining slightly, but remains high. According to the most recent data from Statistics Canada, there were just over 96,000 arrests for drug crimes in 2015. Over half of those arrests were for possession of cannabis. According to older statistics, fully a third of all people found guilty of drug supply offences were sentenced to jail time. And for those with a drug dependency, the risk of re-offending is much greater.

Some drug policy advocates have long said charging those struggling under drug dependencies with crimes exacerbates the problem, and have called on the government to decriminalize illicit drugs.

Although specialized drug courts have been around for years, only about 1,000 people in Canada have participated in them since 2007, and one-third of those actually completed the program. They are only created at the behest of lawyers and judges who see value in introducing them to a particular jurisdiction, which means the vast majority of offenders don’t have access.

Participants of the Burlington program must initially plead guilty, but usually will see their charges dropped or lessened if they make it through. About 200 people have graduated since the court formed in 2012 — an 85 percent success rate.

The court is back in session and there’s a couple dozen drug treatment cases to be heard, as well as people here admitted into the mental health court. Each participant sits with their caseworker in front of the bench, but there’s a microphone they use to speak with the judge directly.

Justice Brown tells Shauna Atkinson, a woman in her 40s, that she will graduate at her next appearance. She entered the program for alcohol and mental health issues several months ago, and says relentless support from her lawyer and regular therapy sessions have helped her cope.

“I keep notes on everyone’s progress,” Justice Brown tells her. “And I’m putting down a note about you today that says ‘superstar.’”

Chantal Jepson, a woman in her 30s with bleach blonde hair and a faux fur coat sits down with her court support worker and takes the microphone. “A new thing I’ve been doing is going to NA [Narcotics Anonymous]!” she tells Justice Brown. She’s in the program on charges related to her crystal meth addiction.

“That is good to hear,” Brown replies. Jepson tells him she’s interested in taking some criminology courses, and laughs and winks when she says she’ll need a pardon first.

“I’ve been in traffic courts that were more cutthroat than this.”

“I’m very proud of you,” Brown tells her to continue with her recovery plan, before moving onto Dylan Petty’s case, who the crown says is “on the naughty list.”

Petty is wearing a yellow reflective vest and takes Jepson’s spot. The Crown tells the judge that Petty has been cancelling therapy sessions and skipping court dates.

“He hasn’t done anything with respect to this program,” he states. “We have a lot of people who want to get in, your honour. He has to make a decision as to whether or not he’s actually going to participate.”

The defence and Crown attorneys take turns giving Petty advice on how he might balance his work schedule with meeting his obligations to therapy and providing urine samples.

“Sometimes it’s about putting his health and wellbeing first,” the defence says. “If that doesn’t happen, he’s going to have to go back to regular court.

“But sometimes that first step comes later, so that’s what we’re hoping for with Dylan.”

Justice Brown agrees, and give him another chance. “See you in December,” he says. Other participants throughout the day admit to relapses, including with heroin and other powerful opiates, but they all get words of encouragement and another court date to prove they can keep their end of the bargain. No one gets kicked out today.

Erin Horlings, an addiction clinician who’s been working with the court since it started, sits outside after attending her clients’ hearings.

“The current criminal justice system is flawed and people get misguided in it, because once they’re labelled an addict or a drug criminal, it’s hard for them to claw their way back into society. That’s why we do what we do,” she said. “There’s no reason why someone who’s been charged with a crime who suffers from a drug problem can’t be offered rehabilitation in tandem with their proceedings.”

But Horlings added that there’s unintended consequences when a court takes on a more therapeutic role. “It means that people in my industry, those on the front lines who have to work with the participants on a daily basis, have to take on more of a punitive role. An approach that’s different from how we’re taught to do our job.”

That includes things like informing the court or the police if a client fails to show up or relapses, an approach they wouldn’t take toward clients suffering from addictions who haven’t been charged with a crime. “And the burnout rate among us here is very high. There’s no extra funding for this program, so all of this is added to an already full plate.”

A 24-year-old man named Stefan — who wished to be identified by only his first name — has his monthly check-in and sets up his next court date. He’s one of the few people admitted into the program with drug trafficking charges, but says it’s easy for people to lie to the court about their progress.

In an interview after his appearance, the Ford car plant worker said was selling drugs to support his expensive oxycontin and fentanyl habit. He and his friends were arrested last year after cops found a slew of drugs in their car.

The drug treatment court set him up with multiple counsellors, therapy sessions and urine screens twice a week. After learning that his girlfriend was pregnant with their daughter, he wanted to stop using, but it was still a struggle.

“I was using someone else’s piss for a long time, and cancelling appointments. I really started using fentanyl for the next six to eight months into the program,” he said. “For hardcore addicts, the program is a lot harder, and dealers could easily get through it and continue doing what they’re doing and get the charges dropped in the end.”

It was only thanks to a near-death experience, after he overdosed while driving and hit another car, that things change.

“I needed a residential treatment from the start. But at the same time, being in the court has helped steer me in the right direction,” he said.

Justin Chevrier would say the same thing. One of the graduates who was lauded at the start of this day in drug court, the stalky 32-year-old stood at the front with a binder full of talking points.

He said he started drinking and smoking weed at age 14 and moved to harder things like crystal meth and opiates by his late 20s. Even though he had a job with a condominium corporation, he sold drugs to support his costly addiction. He tried getting psychiatric help at a hospital in Hamilton, but it didn’t work.

“I’ve been in traffic courts that were more cutthroat than this,” said Chevrier, who was ultimately granted an absolute discharge for the trafficking offense.

He said it was the constant forgiveness of the drug court prosecutor and counsellors, and seeing the sadness when other participants did get kicked out after blowing too many chances, that prompted him to change his ways.

“Eventually I got to abstinence,” he said. “Now I’m a regular blood donor, and next summer I’m going to be coaching a kids’ soccer team … And I’m in university studying to become an addictions counsellor too.”

The court reporter sitting ahead of the judge grabs at a tissue box and dabs her tears.

During a short break, Chevrier stands outside of the courtroom beaming in the stream of congratulations:

“If I hadn’t made it here, I would have been stuck in the other system, where people don’t get better because they’re punished.”

More

From VICE

-

(Photo via Madison County Sheriff's Department) -

WWE -

Ashley Rowland/Moore Police Department -

(Photo by ImagesbyTrista / Getty Images)