Back in 2014, the DJ, record collector and Jakarta Records label owner Jannis Stürtz was scouring around Morocco in search of old vinyl records. He chanced across a second-hand electronics repair store that was previously a record shop owned by a guy who used to run the Mekauiphone music distribution business in Casablanca. “You could still see in the back there were stacks and stacks of records,” recalls Stürtz.

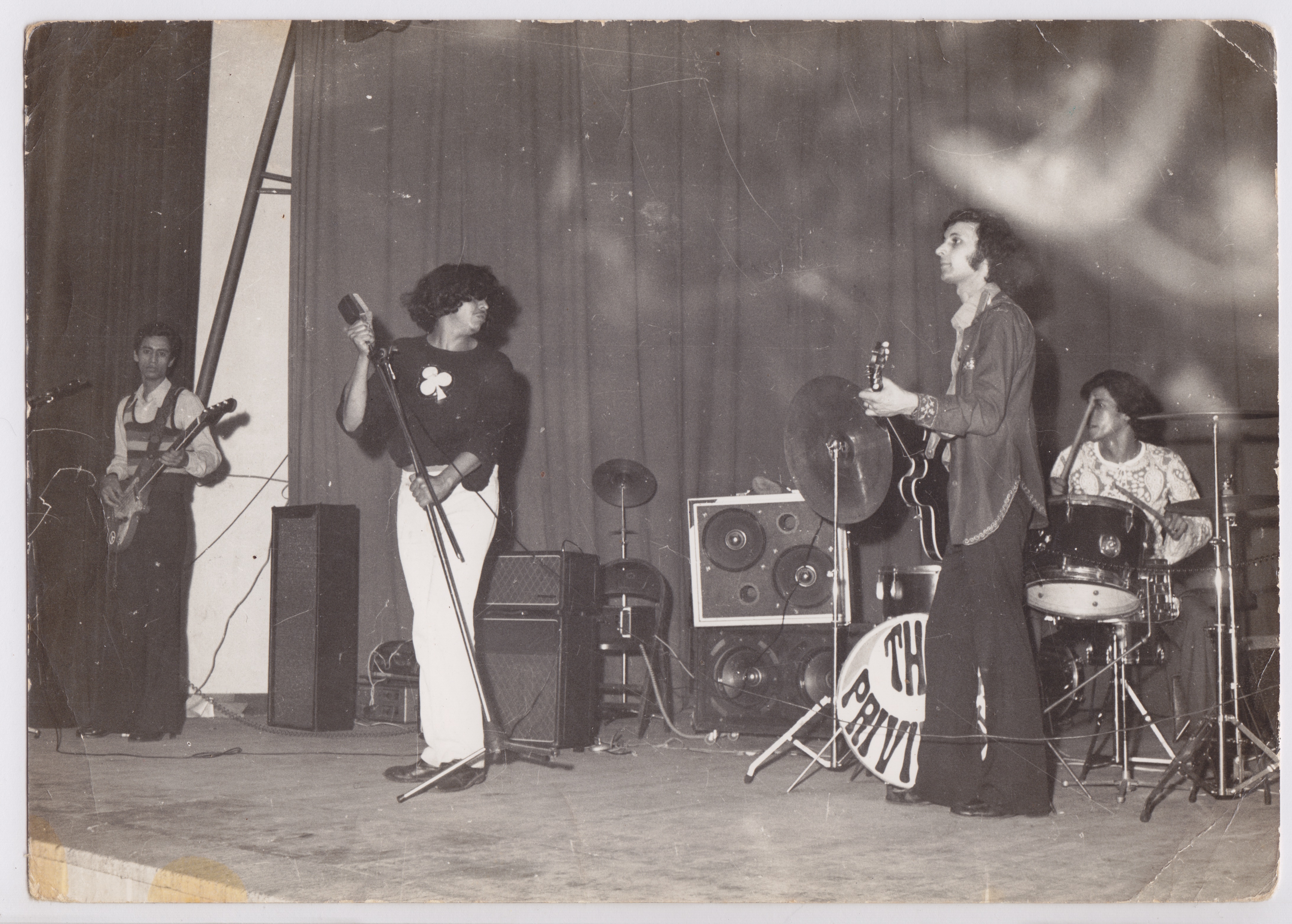

Digging through the pile of dusty vinyl, a track by a local artist named Fadoul caught Stürtz’s ear: Titled “Sid Redad,” the stripped-down song was basically an adaptation of James Brown’s funk anthem “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” but sung in Arabic. This moment kick-started Stürtz’s deep dig into the world of Arabic music from the ’70s and ’80s that mixes up local influences with western funk and soul touches, and was recorded by often obscure musicians sporting fashions that could have been “straight out of a nightclub scene from Harlem in the ’70s.”

Videos by VICE

The Habibi Funk compilation (put out via Stürtz’s Habibi Funk label back on December 1st) acts as an introduction to the micro-genre. “The term habibi funk didn’t historically exist but around five years ago I was doing these mixes that were just called things like Mix Of Arabic Soul, Funk And Jazz Music,” explains Stürtz from his base in Berlin. “Then someone left a comment that used the term and we kinda embraced it.” He adds that searching for “habibi funk” auctions on eBay has since become a thing, and the name has been used to refer to the niche genre.

“You have very specific stereotypes about what constitutes Arabic culture and you also have people who want to look for a different cultural narrative,” Stürtz adds. “So I’m not trying to make habibi funk bigger than it is—it’s a very tiny piece of a bigger puzzle—but I want to present a different story from the stereotypes.”

The Habibi Funk compilation pulls together tracks from countries including Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan and Lebanon that fuse together local styles with infectious brass and guitar riffs laid down over syncopated percussion. Fadoul’s “Bsslama Hbibti” rolls along with raucous drums and hypnotic, swinging guitar lines; Kamal Kelia’s “Al Asafir” hits home as saxophone-powered deep funk mood music; while Samir & Abboud’s “Games” is a breezy jam that owes a debt to Steely Dan and comes off as a lost yacht rock classic.

Stürtz says this fusion is key to understanding the Habibi Funk vibe: “It’s music from the late-’70s to the mid-’80s where musicians from the Arab world tried to bring together musical influences from their regions with influences from the outside and created this hybrid sound. So you’ve got this distinctive Arabic experience through the language and certain sounds but you’ll also get a funk guitar lick that you recognize from elsewhere.”

While connecting these musical styles together, Stürtz mentions how the influence of James Brown runs deep through this community of musicians—and Fadoul (who passed away in 1990) is cast as the scene’s own version of the Godfather of Soul. A maverick of his time, Fadoul recorded music and worked as an actor, did a four-year stint as a circus clown, cut an orange juice jingle for a Moroccan brand, and even dabbled with hip-hop in the early-’80s by rapping over grooves from the Tom Tom Club.

“Fadoul made some really wild music back in the days,” explains Stürtz. “A lot of it was talking about depression, drugs and drinking. One of the songs I came across has a very distinctive funk influence but Fadoul plays it in such a raw style it has this punk rock-ish attitude and feel. On the original Moroccan 7-inch you hear a super loud bass line for two minutes, then they realize it and turn the bass down—some engineers would start the recording over but they were all too high to care so they just turned it down halfway through the song!”

With Fadoul’s lyrics occasionally delving into topics that were darker than the era’s mainstream Arabic music, and sometimes depicting drug and drink use, Stürtz says he likely escaped censorship or controversy at the time due to his underground status. “Most of these countries had fairly restrictive laws and regulations in terms of what you were able to say and most of these songs were recorded in political setups where freedom of speech had certain limitations,” he explains. “So Al Massrieen, the Egyptian disco band, had a track where if you read between the lines they were calling for the right of women to get a divorce, which wasn’t possible then. It caused the band a lot of problems.”

To avoid censorship issues, Stürtz adds that the Sudanese artist Kamal Keila settled on the tactic of singing in Arabic when recording songs about love and day-to-day topics, but switched to English when he wanted to become more political (such as advocating for peace between Muslims and Christians and striving for a unified Sudan). “This gave him more freedom because more people didn’t necessarily understand it in English and the danger for him to run into trouble was more limited,” Stürtz says.

Along with finding ways to evade censorship, many of these figures recorded their music against a backdrop of war—which often prompted the artists to create upbeat or love-based music as a way of dealing with the tumult around them. Included on Habibi Funk, the AOR-sounding “Games” by the singer Samir Rafraf and the bass player Abboud Saadi is a prime example. It was cut at By Pass Studio in Beirut, which was run by “a big integrated figure in the Arab left” named Ziad Rahbani. “It’s like a classic relationship song,” says Stürtz, “but it was recorded in the middle of war in Lebanon. Music like this was a way of fleeing the harsh realities of Lebanon at the time. So this is political by not being political at all.”

Whether creating music in war-torn environments, addressing social justice issues, or just laying down funky grooves, most of the artists showcased on Habibi Funk veer to the obscure side, often having recorded and pressed up only a couple of hundred copies of a solitary 7-inch vinyl record. The group Dalton gigged as a hotel band at the Sahara Beach Resort on the coastline of Tunisia and used the money they made to journey to Italy and record “Soul Brother,” a smoky, wistful funk outing. Some of these tracks have since become collector’s pieces: The last publicly auctioned copy of the Sudanese jazz pioneer Sharhabeel Ahmed’s swinging “Argos Farfish” sold for $1,600.

At the other end of the popularity spectrum, Al Massrieen was masterminded by Hany Shenoda, an Egyptian producer who was also behind the boards for a couple of projects by the singer and actor Mohamed Mounir, which Stürtz estimates easily sold “millions of copies on tape.” Hamid Al-Shaeri, who popularized the Egyptian pop genre jeel, also clocked up sales in the millions; his calling card in the funk world is the modern soul-influenced “Ayonha.”

Listening to Habibi Funk today, you’re struck by the way fierce drum loops and hypnotic brass and keyboard riffs define many of the songs. It’s the sort of stuff that hip-hop producers have been building rap songs around for decades—although Stürtz says that, as far as he’s aware, habibi funk has yet to be utilized as a sampling source. “Some of this stuff is too obscure to sample yet,” he contests, before teasing that he is aware of “one producer who has an Arabic background who might want to do a remix project…” Stay tuned.