Patti Smith’s boyfriend, the gay New York artist who died of AIDS, the man who took a picture of fisting and called it art: However you know of cult photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, it’s strange that we know so little about the man himself. Famed for shooting male nudes, the scandal of the homoeroticism in his pictures has overshadowed both the artist and work itself.

His photos are striking, even today still reasonably shocking, and unflinching. Patti Smith describes it best in her memoir of their life together, Just Kids, when she says, “Robert took areas of dark human consent and made them into art. He worked without apology, investing the homosexual with grandeur, masculinity, and enviable nobility. Without affectation, he created a presence that was wholly male without sacrificing feminine grace.”

Videos by VICE

Twenty-five years after his death, we are more intrigued than ever before. Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, the duo behind RuPaul’s Drag Race, have made a documentary for HBO which aims to dig some way through the controversy in order to truly chart his life, loves, and creative work. I spoke to them about Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures and what they discovered about the man along the way.

VICE: We’re introduced to Mapplethorpe as a little boy, which is a stark contrast to the sexualized art-and-leather man he’s been immortalized as. You offer up the tiniest but most brilliant details about him.

Fenton Bailey: When you make a documentary, the devil is in the details, and details help conjure up a person for an audience. Rather than having an art critic pontificate about his work, you get more insight about Robert’s character and personality when you know he held the local nonstop pogo stick record. Why? It speaks to his stick-with-it-ness, his determination. Or the fact that Mapplethorpe said as a child he knew he wanted to be an artist, “whatever that was.” Even before he knew what an artist was, he wanted to be one.

He’s anything but a lovable character in this film. He’s single-minded and at times borders on cruel—I’m thinking of his treatment of his brother, Edward. When he poses a threat by branching out to be a photographer himself, Robert tells him he should change his last name, so they aren’t associated. Did you go into the project liking him, and did that change?

Randy Barbato: For us, during the first year making it, we were ambivalent about our feelings toward Robert Mapplethorpe. Things that he did, particularly to his brother, made it hard to identify and connect with him from a traditional moral point of view. But the further we got into making the film, the more we admired his brutal honesty. It’s not something you see that often. It’s rare you see someone not edit out the qualities that most would judge as being selfish, ambitious, heartless, or insensitive. Why do we as a society think that ambition is wrong? That quality is simply how some people get things done. We’re all complex individuals, and I think Robert Mapplethorpe in his naked ambition reminds us of the complexity of humanity.

Fenton Bailey: The film definitely forces you to get past what you think of as traditionally likable and not-likable, though. I can understand if people watching come away not liking him.

You show his ambition as relentless, with an awareness of publicity and criticism that’s rare to see. He repeatedly asked, “Will people write about this work?”

Fenton Bailey: It wasn’t enough for him to sit in his loft making beautiful art; he had to position that art. People think that’s not what pure artists do, but I was in the National Gallery last weekend looking at these old master artists and realized this is true with all artists throughout history. You don’t end up painting the Vatican ceiling without kissing the pope’s ass. Throughout art history, artists have needed patrons, and they’ve had to hustle to get work recognition. Twenty-five years later, people still think of Mapplethorpe. There were some artists working with male sexuality at that time—where are they now? It’s a valid part of being an artist.

Randy Barbato: Artists now are so openly ambitious. Back then you couldn’t admit to it.

Patti Smith is shown and spoken about, although she doesn’t appear. It felt like you discussed what was relevant from that time in terms of his lifespan and career: their determination to be artists, her sacrifices to put his career before hers, and most importantly, her pride.

Fenton Bailey: Absolutely, it was about those two points. It’s important to realize that Mapplethorpe had many intimate collaborators and almost all of them are in the film. He was just like that; he was very intimate to that level with a number of people.

Randy Barbato: Patti had a beautiful relationship with him, but that was one part of his life. She actually wasn’t around in New York or his life during a significant part of his artistic career. So she’s in the film to the extent that she was in his life.

One thing you show well is his sensitivity, which comes through despite his “faults.”

Fenton Bailey: He was a highly sensitive person. Very good to his friends, very caring, loving, and with a great sense of humor. Listen to how soft spoken he is. He’s such a gentle, polite person. It’s not what you’d expect.

The way he worked seemed to have been: picking up a man for sex, sleeping with him, and taking photos of him almost immediately.

Randy Barbato: The thing about Mapplethorpe is he didn’t draw the line. He was the work of art. Nothing was off bounds because his life was art. Remember, he said himself, the whole point of art is to open ourselves up, open our hearts, our minds. He took that job very seriously and in many ways sacrificed his entire being to the cause.

Someone in the documentary accuses him of exploiting these people.

Fenton Bailey: In the trial after he’d died, the pictures were put on trial for obscenity, but they were safe because yes, they are obscene, but they have artistic merit. Why does it have to be one or the other? In terms of the models he picked up, had sex with, and shot, it’s sexual desire and desire to turn the body into art. There isn’t a distinction between making love with someone and taking his photograph.

During the end of the film as he knows he’s dying of AIDS, his desire to produce and self-curate is in overdrive. Shooting extensively, throwing a “going away party.” I saw parallels with David Bowie and Blackstar.

Fenton Bailey: Yes! Exactly. Except, of course, Mapplethorpe was doing it many years before, and the equivalent of Blackstar is that show, The Perfect Moment, where he put together those pictures for the first time. He literally was building a time bomb. I don’t think he was necessarily interested in politics or censorship or freedom of speech, but he knew what they could do for him. And they would make him a world-famous artist. The scandal did just that.

Often the fame narrative is either that someone gets famous for his or her work well after death or spends his or her life as a star. But with Mapplethorpe, he spent his final moments tasting that fame he’d always craved.

Fenton Bailey: And spent that time thinking, What can I do considering I am dying that can make me more famous than I’ve been so that my work will last?

The article Vanity Fair wrote about him, almost talking about him posthumously, was awful. It isn’t clear in the documentary, but did you find out if he’d read it himself?

Fenton Bailey: Oh yes, he did see it. It wasn’t in the film because there was so much we had to leave out. The headline of the piece was “Mapplethorpe’s Long Goodbye,” and his reaction was, What? Am I dying too slowly for Vanity Fair? Do they want me to speed things up a bit? He was very upset over it.

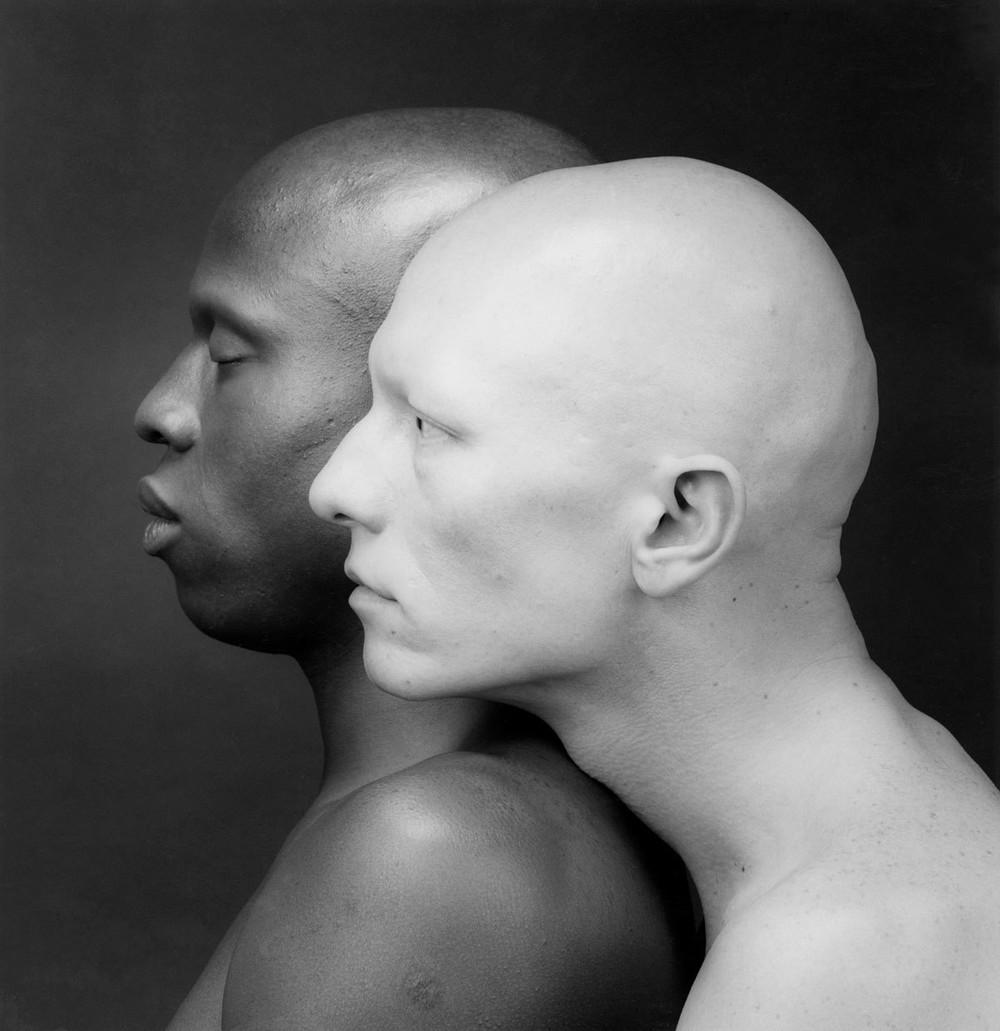

‘Panorama,’ Robert Mapplethorpe

How do you think he would have adapted to today’s art world and wider culture?

Fenton Bailey: I think he would’ve loved where we are right now because the male body and nudity is an accepted part of art. I promise you it was scandalous when he first did it. I think he’d love digital photography and the culture in which everyone’s taking selfies, often nude selfies, whether it’s Tinder or Grindr. He’d love the way careers changed. In the past, you were a painter, or a designer, or a director, but now if you’re an artist, you can do all those things. You don’t have to pick a discipline and stick to it. Creating work can be simultaneously multi-disciplined. He’d have survived well.

To what extent did he change our attitude to male nudes and sex in art?

Fenton Bailey: He’s a pioneer. Without his male nudes, Calvin Klein never would’ve done that campaign with Marky Mark. It’s impossible to imagine where we are today without him. Shooting those sexually explicit selfies and saying these are art and forcing them to look at them was a huge step toward normalizing it, so people could get over the shock. He was a disrupter.

Randy Barbato: Contemporary photography wasn’t even considered art when Mapplethorpe was alive. Gays weren’t running around calling themselves gay. Images of male nudity and sex like his were not seen. It was two different worlds ago.

Since Patti Smith’s Just Kids, we’ve seen a lot of exhibitions and films about Mapplethorpe. Why this interest now? Why so relevant?

Randy Barbato: Before he died, he set up a foundation to promote his work, and following his directions very closely, they gave a huge body of work to LACMA and Getty. The fact there are these two huge retrospectives at these specific museums is because of him and his intention. The reason he’s around today is because that’s the way he planned it. Why now? This is an important time to reexamine Mapplethorpe. People are closing borders, closing their minds, closing their hearts. His art challenges us to open them up again at this important time.

Follow Hannah on Twitter.