WARNING: THIS POST CONTAINS GRAPHIC IMAGES

Jérôme Sessini claims to have gotten into photography by chance. Initially interested in capturing the landscapes and inhabitants of his small hometown in eastern France, he has since gone on to work all over the world—with Latin America and the Middle East being two of his recurring areas of interest. In 2012, he published a book on the Mexican/US border cities that are plagued by drug trafficking and violence. That very same year, he joined the Magnum team.

Videos by VICE

Recently, his photographs of the Ukrainian conflict were awarded both first and second prize in World Press Photo contest’s “Spot News” category. He’s said that at first he was reluctant to travel to Ukraine, explaining that he didn’t want to be the kind of photojournalist who “goes to a demonstration and then just flies back.” He finally changed his mind when he realized just how important the situation there could become. Jérôme ended up bringing home some of the most spectacular photographs of the 2013 assault on Kiev’s Maidan Square, and was one of the first journalists to visit the site of the Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 crash.

Since then, Sessini has been working on a new book dedicated to the Ukrainians living in the east of the country—a zone mired by the conflict with Russia. “I’m interested in people who have fallen victim to superior forces, people caught up in torment that exceeds them, people who are the greatest losers of history,” says the photographer. “Their only crime was being born in the wrong place. It’s made me ponder the question: Should we just say ‘You were born in a poor and crappy country and your life is doomed to failure,’ or is there a way out? I try to keep hope alive.”

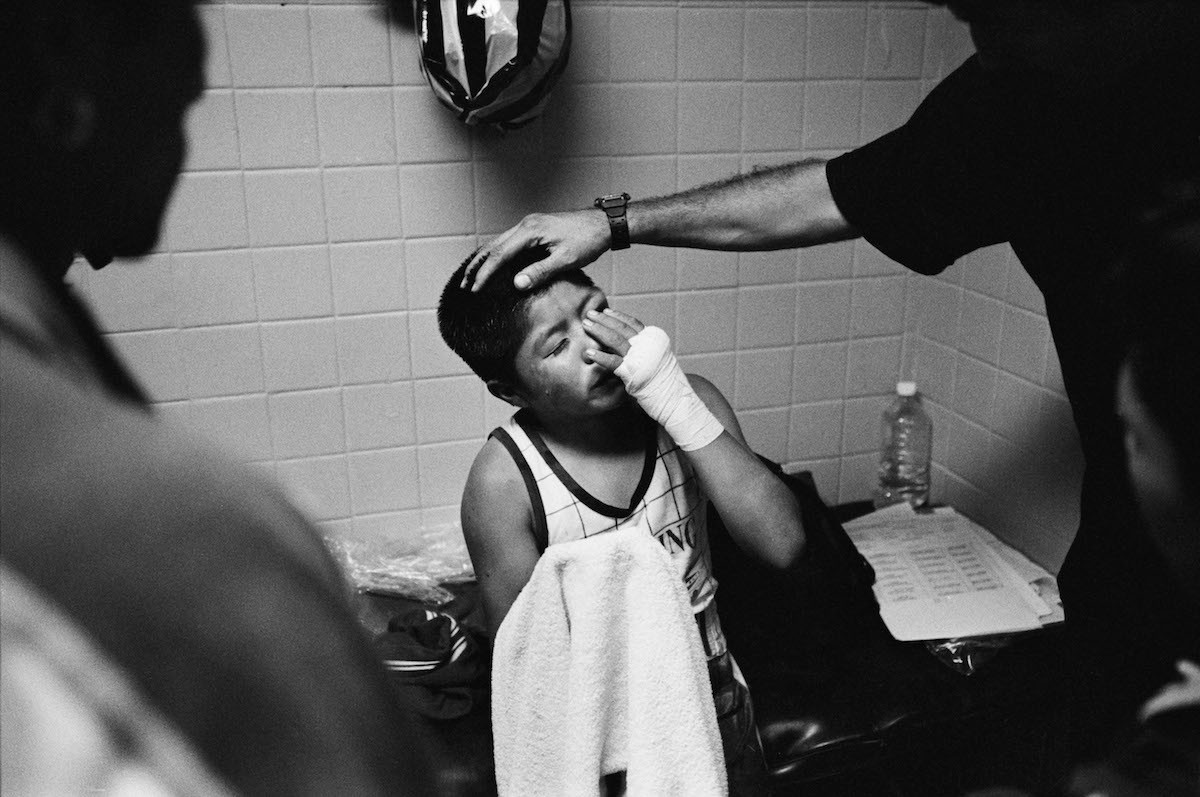

Mexico, Mexico City. 2001. Nuevo Jordan gymnasium.

VICE: How did you get into photojournalism?

Jérôme Sessini: I left my hometown and moved to Paris to learn about photography in 1998. I only planned on staying there for a few months. I started freelancing for the Gamma photo agency. One morning, as I was walking around in the office, my editor told me that he was looking for a photographer to send to Albania as soon as possible.

At that time, there was a war going on there. The assignment was to follow a bus full of Kosovar volunteers, who lived in France before, as they tried to join the ranks of the Kosovo Liberation Army. An hour later, I was on my way. I wasn’t prepared at all—all I had was 30 rolls of film and 5,000 francs ($840) in my pocket. That was my first international story. Later, I became fascinated with boxing and Mexico. It was a dream of mine to go there and meet the champions and fans of the sport. That dream actually came true in 2001.

These days, you’re probably best known for your photos of conflict zones. Do you think the label “war photographer” is appropriate?

I don’t see myself that way; I’m a photographer who sometimes travels to conflict zones. For me, war photographers are those who spend six months at the front line with soldiers—those who really experience war. In my case, I didn’t really choose war. I don’t consider myself a photojournalist either—I’m not chasing after photographs that illustrate a given event.

First and foremost, I’m a documentary photographer. What I find important in my photography is the notion of authorship. Photographers must think of themselves as authors and not just as people who document facts. We need to say: “I’m an author and I am responsible for what I show you and I chose to show it to you because I felt it meant something.” We can’t be neutral when we take pictures. I’m never neutral and I don’t believe people who claim they are.

Iraq, Najaf. August 26, 2004. A civilian falls on the ground during a shootout. Thousands of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani supporters converge in Najaf after a calling from their leader to find a peaceful solution to the crisis in the city, where the Mahdi Army, loyal to radical Shiite Sadr Muqdata, besieged the shrine of Imam Ali.

Why did you get into photography?

One of the reasons that I started was that I’ve never trusted media. Whenever I watched the news, I had this feeling that I was only shown one side of the story. I thought it was necessary for me to experience these events so I could get a better overview.

Your war pictures are characterized by a certain artistic approach. Is that on purpose?

I don’t think I’d call it an “artistic approach,” but yeah, it’s something that I do on purpose. This is where you see the selfish side of photographers. What interests us above all at Magnum is photographic language and photographic writing. I’m into photographs that don’t need text to be understood, photographs that can exist by themselves. Light and composition are things that I’m always after.

Ra’s Lanuf, Libya. March 9, 2011. The rebels are trying to advance against Gaddafi’s army and take the town of Bin Jawad.

You published a book after working in Mexico for several years. How was it being over there?

Their culture is a mix of Indian, Aztec, and Spanish philosophies. At the same time, they are in a way very submissive toward people from abroad. This contrast interests me a lot. They can be very violent and then very soft; very macho then completely subdued; revolutionaries then fatalistic.

Have you noticed a change in Mexican society over the years?

In 2007, the government launched an offensive against the cartels. It totally upset the balance. By weakening some cartels, the Mexican president created a vacuum for others to come in and take advantage of the empty space. It instigated a real war between drug traffickers.

I wanted to work on the impact that these events have had on Mexican society. The cartels used to hire professionals when they wanted to kill someone but gradually, as the police and the army killed their traffickers and their hitmen, cartels began hiring teenagers to do the job. The teenagers weren’t exactly trained and would just fire randomly and constantly. One evening, I was at a bar with friends. The next day, I’d heard there had been a shootout at the same bar and five people had been killed. I saw a lot of crime scenes in bars.

Mexico, Ciudad Juárez. December 15, 2009. A homeless drug addict is sitting in front of an abandoned house called “La Maldita” in the city center.

You also traveled to Iraq during the US invasion. How was that?

I first traveled there in 2003. Back then I was working on the daily lives of the Iraqi people. I took the first pictures of an Iraqi resistance group in November 2003. They had just shot down an American plane.

In late 2004, it became very dangerous to work in the country—that’s when the first kidnappings of journalists started. I thought it was getting too risky, so I decided to embed with the US Army even though I was a bit reluctant at first, probably because of my distrust for authority. Eventually, I had access to everything. They let me work in total freedom, though some of my photos didn’t show them in the best light. For example, I photographed a Marine unit throwing the bodies of fighters from a roof in Fallujah. By the way, no newspaper has ever wanted to publish these pictures.

Have you been confronted with similar dangers in other countries?

I experienced similar dangers in Somalia in 2006. The Islamic Courts Union had just seized Mogadishu at that point. I felt like I could get kidnapped or killed at anytime. I had five armed guards following me around constantly.

Danger is more obvious when you’re in a combat zone. You don’t have a lot of time to figure out where you shouldn’t go and where you can take shelter. There’s exceptions though; take Libya, for example. Everything was happening in the desert and there was no way to protect yourself.

Syria, Aleppo. October 20, 2012. Bustan al-Basha front line. Free Syrian Army rebels are trying to rescue a 19-year-old civilian who was shot in the throat by a sniper from the loyalist army while he was crossing the avenue.

You made two trips to Syria just before the emergence of the Islamic State. How was that?

I remember arriving in the country in October 2012 and meeting my fixer in a hospital in Aleppo. A bombing had just taken place. It was a real massacre. There were wounded people and blood everywhere. It was absolutely horrific.

On my second trip—three weeks in February 2013—I had grown tired of fighting and wanted to work with war landscapes and create a portrait of Aleppo. Shortly before my departure, I realized that it would soon become impossible to set foot in the city again—we were beginning to hear reports of groups like Al-Nusra Front arriving, as well as talk of ISIS. The rebels were already talking about how, once they’d defeated the regime, these Islamist groups would be their next enemy. Two days after I returned home to France, my fixer was killed. Four months later, Didier François and Edouard Elias were abducted.

You once said that “No matter whether they live in Iraq, Mexico, or France, it’s always ordinary people that lose the most.” Have the recent events you’ve been covering changed your mind at all?

I’m fully convinced of this fact. Look at the Arab revolution: It began with demonstrators who had legitimate demands but what happened afterward wasn’t positive at all. People need support to advance. The problem is that when powerful countries support them—in the case of Libya, France, and England—they often end up taking over and driving people away from their original aims. France and England were never concerned about what would happen following Gaddafi’s death.

The fall of Gaddafi—who was able to contain some of the problems—caused chaos in Libya. Today, the real victims are the Libyans and many now regret toppling the dictator. On a personal level, these recent revolutions have taught me to trust my first impressions. They force me to think thoroughly about my trips and strive to gain a good understanding of the geo-political and cultural issues of the countries I’m visiting.

Check out Jérôme Sessini’s work on Magnum Photos’ website.

See More of Jérôme’s Photographs below:

Ukraine, Donetsk. November 30, 2014. A man sleeping on a makeshift bed in a bomb shelter for civilians in Kievsky district, near Donetsk airport.

Iraq, Baghdad. November 17, 2004. After the offensive on November 8, Marine units take up positions in the northeast of Fallujah. Insurgent groups were still fighting against US forces, who had the task of “cleaning” the city house by house.

Mexico, Ciudad Juárez. November 26, 2011. Children playing outside their house.

Tunisia, Ben Gardane. February 28, 2011. Border with Ras Adjir, Libya. People are leaving the violence in Libya to seek refuge in Tunisia. Most of them are Egyptian and Tunisian workers.

Somalia, Mogadishu. June 2, 2006. Fighters from the Islamic Courts Union are about to face the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism, near Keysaney Hospital. On June 5, after four months of fighting that resulted in the killing of 400 people and injured 2,000 others, the Islamic Courts seized Mogadishu.

Ukraine, Kiev. February 19, 2014. Anti-government protesters are rallying against riot police and building barricades on Maidan square. The day before, at least 18 people, including seven policemen, were killed.

Libya, Tripoli. August 24, 2011. Anti-Gaddafi rebels capture the last areas controlled by the regime.

Syria, Aleppo. February 16, 2013. Al-Amria front line.

Ukraine, Rassypnoye. July 18, 2014. Miners and rescuers are looking for victims on the crash site of flight MH17.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Sony -

Screenshot: HBO -

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images) -

Screenshot: Nintendo