In May this year, the European Court of Justice ruled that employers weren’t monitoring their staff closely enough. Spain’s largest trade union had taken legal action against Deutsche Bank SAE back in 2017, arguing that too much overtime was going unrecorded. When the case was put before the ECJ, they agreed, overturning the judgment of the Spanish supreme court: in order to meet their legal obligations, more monitoring was necessary. Companies across Europe would have to start keeping closer watch of their employees.

It’s a significant development, but unlikely to be greeted with much enthusiasm from your average worker. Especially those with direct experience working under the digital eye of existing monitoring software – the programmes that keep a timer running on your screen, pausing if your mouse or keyboard goes too long untouched. These employee monitoring systems are at the more intrusive end of the spectrum, and they hold a particular appeal with companies who use self-employed contractors. It offers them a win-win of avoiding the holiday and pension liabilities of permanent staff, while keeping extra close tabs on their workers. Seen from that perspective, the ECJ’s ruling looks like another reason to embrace a Luddite revival and saw your laptop in half. But it’s not quite so simple.

Videos by VICE

Advocates of employee monitoring software see it as a constructive way to harness data, assess workers’ performance and maximise efficiency. In an ideal scenario, these tools can be transparent and mutually beneficial. The issue is whether or not the companies who develop this technology are motivated by such ideals. They may simply look to empower employers with a megalomaniacal streak and cash in by appealing to their worst instincts.

“The traditional security tools out there are largely able to go around regulation by using the label of security,” says Ankur Modi, CEO of StatusToday, the only UK-based company working in this area. He stresses that his own platform is a two-way system, designed to help HR and management be more impartial and transparent. The same cannot be said for all of Modi’s competitors. “A lot of Employee Monitoring softwares that are as intrusive as otherwise, they tend not to be used for security. They tend to be used for surveillance.”

Modi feels that compliance needs to be revisited in the industry, to ensure that information is collected exclusively for security purposes. “If you’re using it for surveillance, that is 100-percent within the remit of GDPR and it has to be treated as such,” he says. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) looms large over discussions of such software. A new privacy legislation that gives EU citizens greater say in how their data is collected and used, GDPR aims to improve the transparency with which companies gather information on web users.

This also means it’s very noticeable how few of the businesses developing these monitoring tools are themselves European, and therefore subject to GDPR. The majority are based in North America, but they enjoy a global presence. They bear names that range from the benign-sounding ‘ActivTrak’ to the less-than-friendly ‘StaffCop Enterprise’. Some specialise in simple management tools: online timesheet portals that allow remote workers to clock in and out. Others are far more invasive, recording every single click, keystroke and site visit in real-time, storing a visual record of everything that took place on an employee’s screen during work hours. (StaffCop even offers a not-at-all ominous recording service, boasting on its website: “Hear what happens in the office through microphones connected to computers.”)

Those looking to defend such practices emphasise the high cost of compliance in certain industries: the financial institutions who need protection against even minor incidents of employee negligence. When Modi talks about a “label of security”, this is what he’s pointing to. An all-purpose justification that side steps deeper questions of what this data-collection really achieves. In reality, employee monitoring software occupies an ethical grey area, sped along by tech advancements, which may yet prove untenable in the face of tighter GDPR enforcement.

James Farrar, one of two Uber drivers who successfully sued the company back in 2016, is unconvinced that employees’ best interests could ever be well-served by these softwares. “What’s happening in the gig economy is a canary in the coalmine situation,” he tells me, convinced that negative changes affect the precariously employed first, where the stakes are low and complaints least likely. His worry is that tools such as time-recording and GPS tracking will quickly fold over into undisclosed performance monitoring. He believes his former employers are already doing as much.

“Uber has a profile on me that they won’t share with me,” he says, “and I’m challenging them on it legally. I know it exists because it flashed up on the app one day. I immediately screenshotted it and challenged it – they said it was a mistake and they were testing the system. The performance profile said that I had had instances of inappropriate behaviour, missed ETAs and ‘attitude.’ But I don’t know how to perform for Uber on those categories, because they never told me how and they haven’t told me where I’d infringed.”

When I approached Uber for comment, a spokesperson denied that this was the case, stating that the company had “responded within the guidelines published by the ICO (the data authority in the UK, where Farrar is based).” They also stated that they had “provided millions of lines of data as well as detailed explanations on why we cannot provide some of the specific data he requested.” Uber emphasised that some of the data Farrar had requested would violate the privacy rights of

passengers, who have the right to offer feedback without it being scrutinised by others. This

makes sense, but it puts drivers in another awkward position: having their performance

assessed by passengers with no strict incentive to be objective or fair.

Is it possible that dismissals could be decided through a hidden, automated system as well?

Farrar says that Jo Bertram (Uber’s former head of Northern Europe affairs) was Uber’s witness

during their employment tribunal case, and referred to the company’s dismissals process. Farrar explains: “She said that in 2014 it was mostly a manual process but by 2015, they had mostly automated it.” Indeed the ‘Safety and Security’ section of Uber’s privacy policy outlines that drivers may be removed from the platform “through an automated decision-making process” if their user rating falls too low.

Thanks to GDPR, drivers based in the EU can object to this type of processing, which makes it

clear why new regulation was so necessary. Article 22 of the GDPR exists to prevent ‘automated processing’ of data that could have a major impact on a person’s life. To put it simply: if you’re going to take away someone’s livelihood, an accountable human being must play at least some role in that process. The trouble is that there’s still little clarity on what constitutes a significant human intervention. At a time when hiring algorithms have been shown to reinforce gender and racial biases, there’s every reason to challenge the legality of such systems.

Lillian Edwards of Newcastle Law School has been studying the legal implications of AI for over three decades, and has a healthy degree of skepticism where performance assessment tools are concerned. “There’s an argument made quite a lot that algorithms are more objective than human beings, most of the evidence goes against that,” she says. Edwards stresses that algorithms seem to be more consistent and less chaotic than the human mind, but claims to their objectivity are still largely unproven.

When it comes to employee monitoring, it’s not even clear that a worker can fully consent to being watched so intensely. “What the GDPR says, very clearly, is that consent between an employee and an employer is probably invalid because of the power differential,” Edwards says. “So that hasn’t really worked its way through yet: are these tools going to be legal if the consent is not valid?”

Edwards is quick to point out that there are other grounds which allow an employer to use monitoring software, the key one being ‘legitimate interest’. This has to be proportionate, the ends have to justify the means. But more pressure can still be applied: how far can you justify the intrusion into someone’s privacy just because they work for you? With the use of these softwares guaranteed to grow in the years to come, asking these questions becomes more and more important.

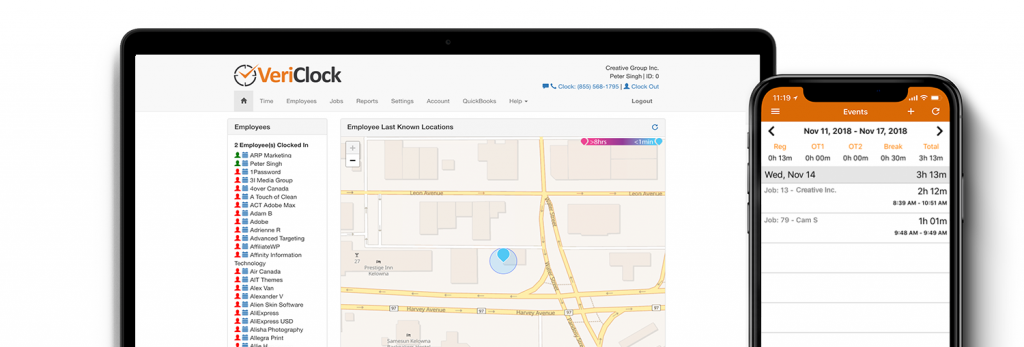

“We’ve seen a steady uptick in UK enquiries and customers in the last year,” says Scott Rees, director of operations at VeriClock, a Canadian company that provides a time and attendance tracking system. He says that consent and impartiality are integral to the company’s ethos. “All we want to do is provide a very clear accounting of employees’ time. Whether that accounting is to the benefit of the employer or the employee is for them to decide.”

Do other companies have less clearly defined ethics? “You can glean from a list of features and capabilities of a piece of software what a company’s view towards ‘employer versus employee’ is, how antagonistic they are,” Rees says. He also admits that some clients come to them because they lack trust in their staff, but says it’s less common than people might think. He generally has little time for intensive surveillance software: “This speaks to me of an application and an employer who has zero trust in their employees.”

When employers show little trust in their staff, it makes you wonder what the worst-case scenario might be. Supposing someone came to VeriClock asking for help in cutting loose an employee they thought was slacking off and not pulling their weight?

“We wouldn’t go out of our way to help an employer skewer an employee,” says Rees, “because then employees wouldn’t use our software, and really, it’s a shitty thing to do to people and we don’t want to be shitty people.”