In the aftermath of the Great Recession, Americans felt increasingly insecure about finding decent, well-paid, middle-class jobs. So thousands of people made the same decision: become a computer programmer.

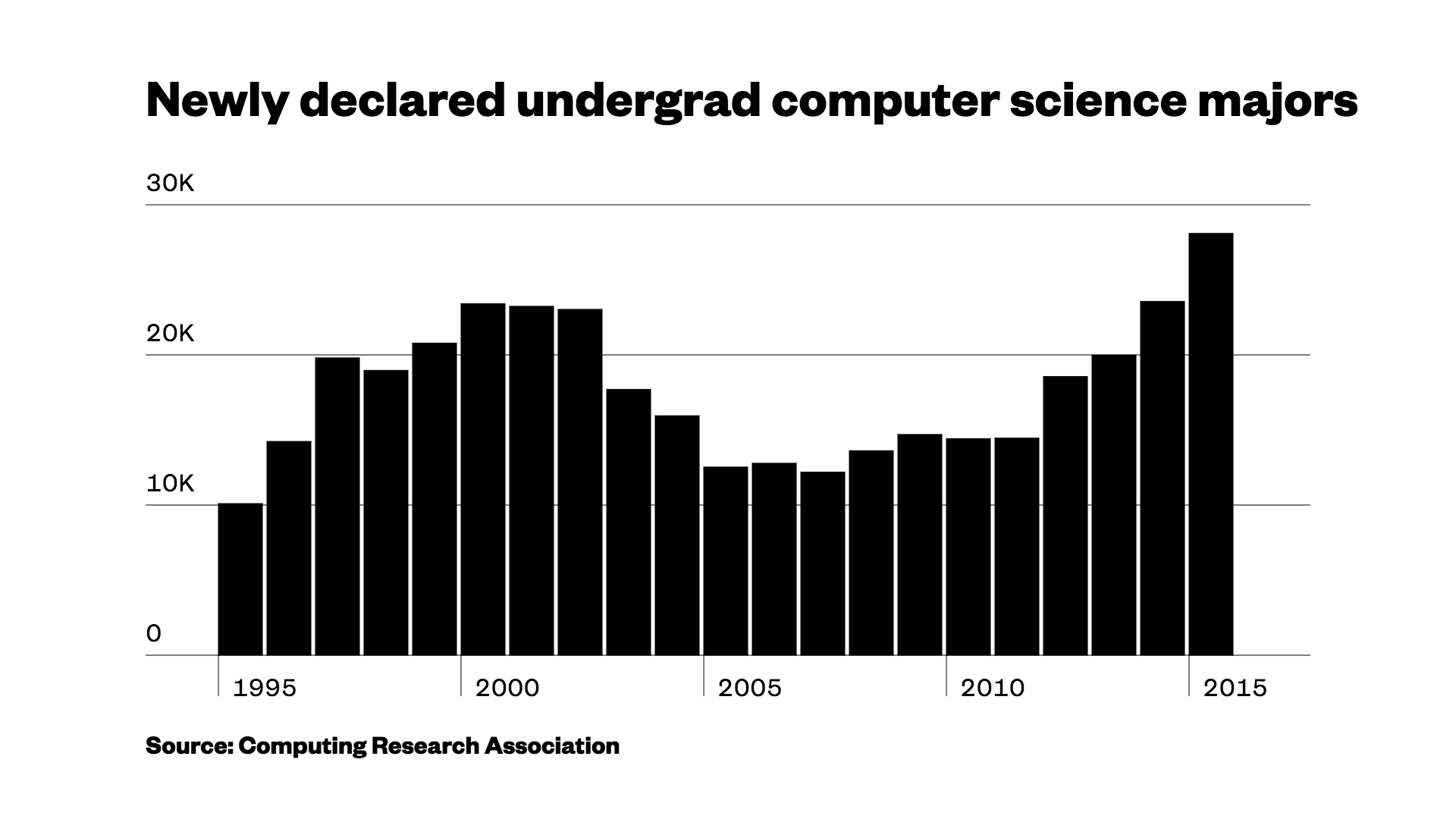

Since 2007, the number of newly declared undergraduates computer science majors has grown 130 percent to more than 28,000. And in 2015, non-degree granting “coding bootcamps,” which cropped up around the country, also churned out roughly 16,000 graduates. The interest is easy to understand. Median salaries in the computer and technology information industry hover around $80,000, and jobs projected to grow faster than average through 2024.

Videos by VICE

But if working with computers and IT were supposed to be the high-wage American jobs of the future, there’s one small catch: a large and growing share of these workers in America aren’t American. That’s a fact that seems to have captured the attention of the Trump, who is in a position realign American immigration policy in a way that could reshape the labor market for technology workers in the U.S.

In 1980, just 7.1 percent of American computer science jobs were occupied by foreign-born workers. That share grew to 27.8 percent by 2010, amid breakneck growth in a tech sector that became increasingly reliant on highly skilled, visa-holding immigrants.

As a candidate, President Donald Trump repeatedly denounced offshoring among manufacturers and low-skilled immigration in an ultimately effective effort to win over some working-class voters. But fewer people noticed that he also periodically — though inconsistently — trained his fire on higher-skilled immigrant workers.

Trump made a campaign issue of a lawsuit filed by former Disney employees in Florida. Those Disney workers had been replaced by foreign workers who they were responsible for training. He claimed on his campaign website that visa programs — such as the one championed by Sen. Marco Rubio, a contender for the Republican nomination — would workers “decimate” American some workers. After seeming to backtrack on that position during a Republican debate, he released a statement confirming his position on foreign guest worker programs, most prominently the H1-B visa program.

“I remain totally committed to eliminating rampant, widespread H-1B abuse and ending outrageous practices such as those that occurred at Disney in Florida,” Trump’s statement said.

Now in the White House, the Trump administration is making changes to the H1-B program, an important source of America’s foreign-born tech workers. In late March, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services announced that entry-level computer programmers would no longer automatically qualify to apply for the visa program. The agency, part of the Department of Homeland Security, issues 85,000 visas each year, with the lion’s share going to Indian tech workers. It also announced early this month that “combating fraud in our employment-based immigration programs” is a priority for the agency.

While the implications of the announcement aren’t clear, it did introduce uncertainty into a system that has grown to be a large cornerstone of the American tech economy. The planned changes also, at least superficially, move to reshape the goals of American immigration policy, prioritizing the prospects of some American-born workers. On the other hand, American companies claim limiting their access to foreign workers hurts their ability to compete by stopping them from bringing talented workers from around the world into the U.S. They say that the U.S. immigration system should aim to encourage talented technology workers to come to the U.S.

“We need to make sure we have a system of immigration that allows that to happen,” says Todd Schulte, president of FWD.us, an immigration reform advocacy group funded, in-part, by several high-profile technology executives including Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates.

Tech firms argue that they need the H1-B program because they can’t find the skilled workers they need in U.S. But critics argue that large presence of foreign workers are simply a cost-cutting measure aimed at keeping a lid programming wages and effectively weaken incentives for would-be American tech workers to learn important skills.

If that is what tech companies are doing, it works. In a 2015 paper, economists estimated that wages of American computer programmers were 2.8 to 3.8 percent lower than they would have been without the presence of visa-holding foreign workers. Furthermore, economists also estimated that the presence of foreign programmers lowered the number of native-born programmers by between 7 to 14 percent. On the other hand, foreign workers help boost GDP, raise overall averages wages, and help the growth of the IT sector as well as the profits of tech companies.

“The economy as a whole wins — and the average worker. But the average does hide some amount of distributional consequences,” said Gaurav Khanna, one of the economists that wrote that paper. “Some people get a thinner slice of that pie.”

If this kind of tradeoff sounds familiar — enhanced overall economic growth at the expense of a specific group of American workers — it’s largely the same framework that economists have used to explain the costs and benefits of trade for decades.

At its heart, these debates reflect a core economic reality Americans have long had trouble accepting: free markets do not exist.

American policy-makers often pride themselves on their efforts not to “pick winners and losers” among workers and companies in the economy. But the truth is that all markets have rules. And the design of those rules can have big impacts on supply and demand, and therefore, prices. For example, the rules that determine whether foreign coders can work in the U.S. either increase or decrease the supply of programmers in the U.S. and, assuming relatively stable demand, increase or decrease how much coders get paid.

America’s trade rules — low tariffs and ineffective enforcement of trade deals — have prioritized the highly educated, service employees people like attorneys and financial workers, consumers and companies that benefitted under globalization, while effectively sacrificing manufacturing employment.

In the U.S., we set the rules through an ugly process known as politics. And the answers we get under President Trump could look quite different from what came before.