“I’ll be talking to someone and say, ‘I did Teeth,’” Joyce Pierpoline exclaims, “and their body language changes completely!”

I’m talking to the producer of 2007 cult horror-comedy Teeth in London’s British Academy of Film and Television. Around me, expensively dressed industry executives tap smartly on MacBooks or raise sparkling toasts to future deals.

Videos by VICE

Pierpoline, a dark-haired woman in chunky silver jewelry and fluffy sneakers, grows animated. “And then,” she goes on, “they’ll turn away from me”—she hunches over, crossing both legs in demonstration—”and be like, ‘Oh, you produced that?”

It’s been a decade since low-budget comedy-horror Teeth premiered at Sundance to positive reviews (its lead, Jess Weixler, received the Special Jury Prize for Acting). Written and directed by Mitchell Lichtenstein, the son of famed pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, the film follows high school student Dawn O’Keefe, an evangelist for the purity movement.

As the film opens with O’Keefe and her stepbrother Brad in a paddling pool, we learn her secret—she has vagina dentata (“toothed vagina” in Latin). Brad attempts to molest her and ends up with a bleeding finger. Teeth follows O’Keefe’s travails as she struggles to maintain her purity vows in a sex-obsessed culture while escaping the unwelcome advances of her abusive stepbrother and rapist classmates. She also tries to look after her sick mom, whose illness appears to be linked to the nuclear power plant O’Keefe bikes past en route to school.

Watch: British Comedy’s Rising Star Michaela Coel on Swapping God for Filthy Jokes

A powerful critique of America’s purity culture, Teeth is also an incisor-sharp commentary on male entitlement, consent, and sexual violence. But despite a mostly warm critical response, Teeth performed poorly at the box office. On a limited theatrical release on January 18, 2008, Teeth barely recouped its $2 million budget. More distressingly, it was outperformed at the box office by Katherine Heigl vehicle 27 Dresses, an asinine rom-com clunker about a perennial bridesmaid. Over time, however, Teeth settled into a new critical importance like dentures in a water glass.

Which isn’t to say that everyone loves the film. One prominent feminist critic I emailed for comment declined to speak about Teeth, on account of it being a male-written, male-directed film. Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, who devoted a chapter to Teeth in her 2010 book Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study, feels similarly. “Just because you’re making a movie about the monstrous feminine, doesn’t give you a free pass into the feminist horror film canon,” she writes in an email to Broadly. “Teeth is a great concept for a film, but the final product feels less concerned about women and their bodies than it does about what women’s bodies can do to men.” Parts of the film have aged terribly with as our understanding of consent grows—specifically a scene where Dawn’s classmate Ryan gives her a sedative before masturbating her with a vibrator. (It’s a mistake that Mitchell Lichtenstein openly acknowledges during our conversation.)

Nonetheless, in the decade since its release, Teeth has won new fans—especially as online streaming opens it up to a younger audience. “I was at a friend’s house in New Jersey,” says Pierpoline, “and her 16-year-old daughter shrieked, ‘You made Teeth? My friends and I love that film!” She practically glows as she tells me about distributing Teeth posters at a screening to an adoring audience of young girls: “It was a really nice feeling.”

“I had a manager at the time who said, ‘Don’t show it [the Teeth script] to anyone,’” Lichenstein tells me over Skype from his home in Maine. “He said, ‘Anyone who reads this will not read anything else you write.’” Why? “The movie industry is still run by men, I guess, and they don’t like the idea of seeing dicks get cut off. Most men don’t want to see that.” As a result, Teeth was put together entirely with private equity. Every film studio—even European ones that Lichenstein and Pierpoline thought might be more liberal about vaginas—turned it down.

If the overt message of Teeth is that jerks get their dicks—genital piercings and all—eaten by dogs, the secondary message is that men will try and obstruct your vagina dentata film at every turn, from the pitching stage to production and post-production. (Incidentally, no dogs were harmed during the filming of Teeth, and the frenum piercing was a custom-made sugar confection from a local bakery.)

Even when funding was secured, shooting Teeth was a grindingly arduous process. “We needed a hospital set, a school and a house,” Lichenstein remembers. Pre-shoot, him and Pierpoline went down to Austin to scout locations. A local film commissioner happily took them to a number of potential locations. That is, until he got wind of Teeth‘s plot. “In between showing us that morning and coming to collect us that evening, he’d read the script. Not only was he not going to help us, but he was calling all the places we’d been, saying it was a pornographic shoot and not to let us shoot there.” Undeterred, the close-knit crew (they wore matching promise rings throughout the shoot—Pierpoline still has hers) pushed on and found alternative locations in the city.

Teeth certainly isn’t porn. Neither is it horror; at least, not really. Although Dawn can, and does, castrate men—bloodied dicks thud to the ground with pleasing regularity throughout the movie— Teeth doesn’t make Dawn a monster. Her vagina dentata only snaps shut when she’s being violated or raped; she is otherwise capable of consensual, non-castrating sex. Unsurprisingly, this metaphor for consent was somewhat lost on the (mostly) male critics reviewing the film. Here’s film critic Jim Emerson on a pivotal rape scene in the film:

Because they’re such unprincipled horndogs who won’t take “no” for an answer, the movie suggests they deserve what they get. Still, when Dawn’s first full-frontal victim looks down to find he’s not even half the man he used to be, he seems genuinely hurt—by the rejection as much as the castration. In a bloody, nightmarish, young-romantic way, it’s kind of touching.

The scene Emerson describes takes place at a waterfall, where a consensual kiss between Dawn and her classmate Tobey turns into attempted rape. (Dawn: “Get off.” Tobey: “You don’t have to do anything.” Dawn: “No! No! Dammit. Stop! Dammit Tobey! NO!”) As we watch Dawn struggle against her attacker, we’re clearly watching a violent sexual assault—but Emerson minimizes Tobey’s rape as “young-romantic” ardor, and reimagines him, not Dawn, as the “victim.”

Like Emerson, movie executives didn’t understand, or want to understand, Teeth. “Either the studio didn’t get it, or it was misogyny. I lean towards it being misogyny,” Lichenstein says. “The distribution company [Roadside Attractions] wanted to sell it as a pure horror, against my objections, and I think it was marketed to the wrong audience. They messed up.

“But the good news is that people feel that they discover it themselves, it’s not pushed down their throats from advertising hype. It’s a word of mouth thing, and that’s a more genuine way of people discovering it.”

Pierpoline pulls even fewer punches when it comes to naming names. A decade on, she’s still pissed off about how its release was handled. “If Lionsgate had done a different marketing campaign and spent more money and gone wider, that would really have helped the film,” she says. At the time Teeth came out, studios were trying to replicate the success of torture-porn slasher franchises like Saw; Saw 3 came out a year before Teeth’s Sundance premiere. “Lionsgate…did so many films like Saw and everything, and we’re not like that.”

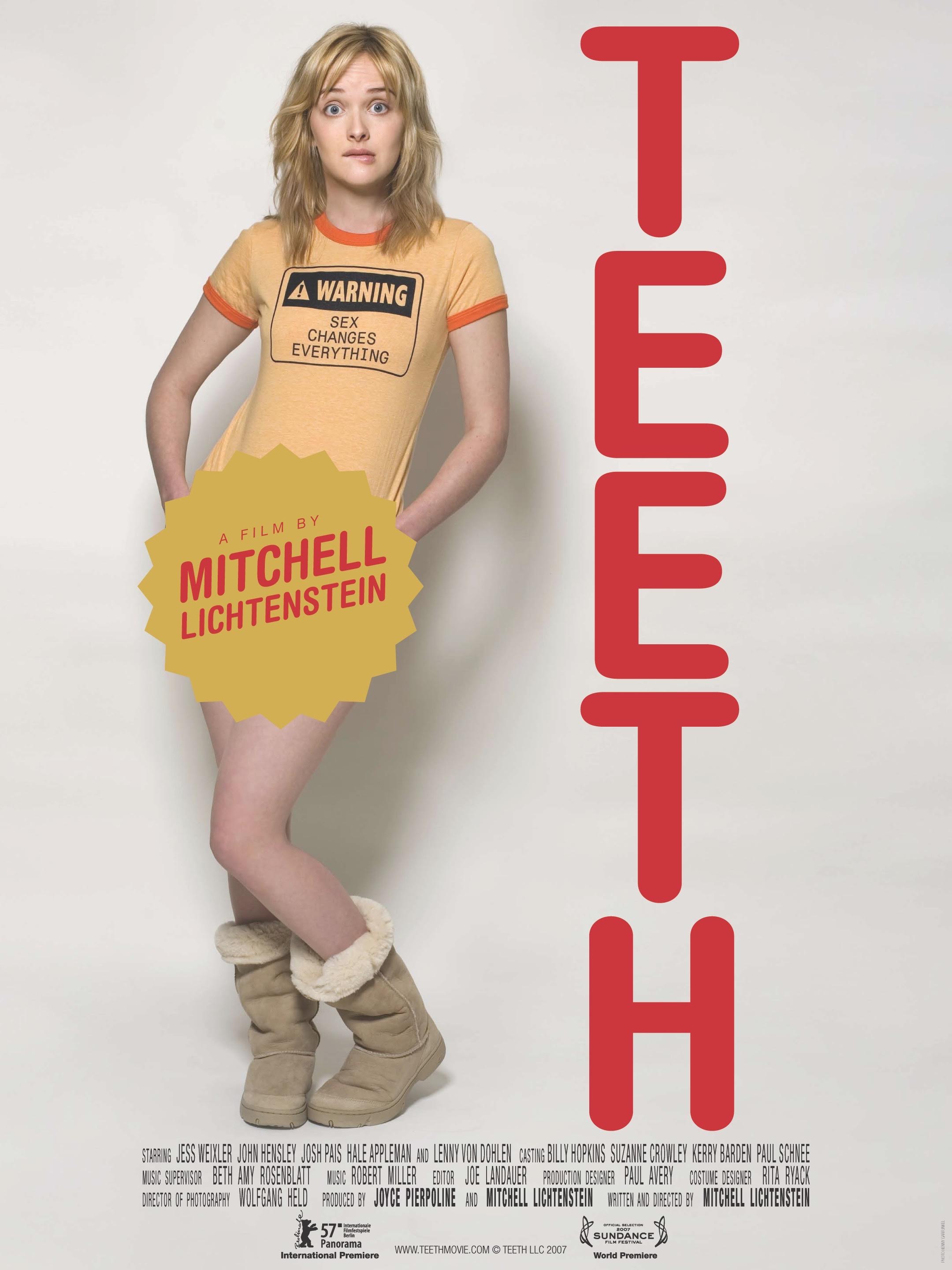

She grabs an iPad and pulls up the marketing campaign they’d originally envisaged for the film. “We wanted her to have this cute kind of look,” she explains, pausing over a publicity poster she and Lichenstein designed. Weixler is pulling down a “Warning: Sex Changes Everything” T-shirt to cover her crotch, which is obscured by a giant gold star, like the one Dawn’s creationist biology teacher uses to obscure a textbook’s page on the female reproductive system. Dawn is chewing her lip with a knowing look, a wry expression on her face.

It’s a radically different poster from the one the distribution company eventually settled on. Lichtenstein and Pierpoline’s poster features a tousled-looking, relatable heroine. It correctly implies that Teeth is a comedy as much as a horror. The poster that the distribution company settled on is styled according to more conventional horror tropes: Dawn reclines in a stark white bathtub, her face erased of any emotion. There’s no trace of the wit or intelligence Weixler brings to the role, evident in the first poster. Underneath, the word “Teeth” is traced in blood red lettering on a black background.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

I was a teenager when Teeth was released, and I remember swerving the film because the poster made it look scary. When I mention this to Pierpoline, her eyes fractionally darken and she flinches in irritation. “I think it was a film ahead of its time, and I don’t think the marketing campaign addressed what it was about. People were hesitant to face it head on.”

Pierpoline and Lichenstein are now trying to pitch a TV remake of Teeth. Despite the intervening passage of time being mostly kind to the film, they’re still getting rejected at every turn. Turns out, a TV show about vagina dentata in 2017 isn’t any more palatable to Hollywood execs than a movie about vagina dentata in 2007.

“We’d love to make it into a TV series with Dawn as a Dexter-type avenging angel, but I don’t think people are necessarily ready for it,” she explains. “A lot of men still run agencies and departments. It’s still a TV show about vaginas.”

Like Lichenstein’s agent all those years ago, executives have pulled Pierpoline aside and told her a TV remake would be a bad idea. She’s still stubbornly refusing to take no for an answer. “I’m like, why not?” she exclaims. “It’s original. It’s fun. It’s about a strong woman.”

Ever the hustler, Pierpoline isn’t about to give up. Before I leave, I find myself promising to send her the relevant VICE contact for her to pitch her TV remake. “So I’ll hear from you,” she says firmly. Who knows? Maybe one day, Dawn O’Keefe will live to bite off another dick.