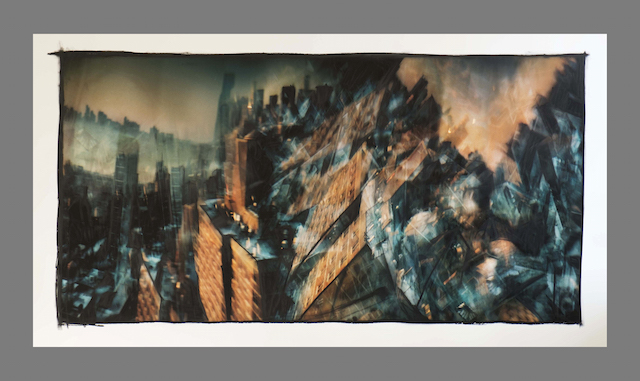

Whether the specters of future skyscrapers, or the smoldering skeletons of societies collapsed, the manipulated photographs of Jacob Felländer are at once filled with signifiers and unfamiliar in what they intimate. They’re both in-process and the end results of processes that span mediums, space, and time. Primarily, Felländer works in photography: each piece is a catalog of captured light. But what breaks his massive landscape portraits free of their time-bound constraints is his use of long-exposure techniques—be they applied over the course of one day, or across continents—and secondary applications of charcoal, and oil and acrylic paint.

Courtesy of Jacob Felländer Studios

On a humid morning in June, hours before Felländer takes the stage at the Stockholm Symposium to give audiences to the conference a window his current works and the future of his practice, I take a car out to the industrial, Southern Stockholm neighborhood where Felländer’s studio is situated, and spend over an hour with the artist talking technique, technology, and the magic in making mistakes.

Videos by VICE

Jacob Fellander, “Sthlm/NC/LA,” 2012.

“This week has been a little hectic, ’cause I’ve had to combine or compress 15 years of communication through art into ten minutes of communication through words,” Felländer tells me over coffee, “which is more challenging than I thought.” The space, in fact, a wide, open loft with a small kitchen, office, and two massive winged rooms, contains many of the works he’s created since graduating from Flagler College in Florida in the 90s, and dialing in on his process by 2004. Originally, Felländer sought his destiny in the states on a golf scholarship. It was in an elective class, in the sleepy town of St. Augustine, that he’d first set foot inside a darkroom. “The door slammed behind me, and I haven’t left yet,” he reminisces. “I sold my golf clubs and bought a brand new Nikon.”

That Nikon, however, would soon be replaced for far lower tech after an influential professor gifted him a shoebox camera. Rather than the crisp, perfected images he’d set out for, Felländer found beauty in fearfully flawed and fragmented frames. “I started getting things on the negatives that were strange and then after awhile, I realized they were interesting. And then, after awhile, I realized that, because [the camera was] so simple, I had the freedom to do anything.”

Today, his images seem to do everything. They travel the globe, bounce effortlessly between digital and physical channels, and even become physical sculptures: after Felländer discovered the possibilities of ink, paint, and charcoal to break certain figures free of their photographic surfaces—part of a series now known as Pentimento—he soon realized that he could use CGI techniques to not only give 3D forms to 2D images, but with the help of 3D modeling and printing, actually create objects where there was once only light and shadow.

As announced during his Symposium Stockholm speech, Felländer is also now making his once-analog photographs into fully VR-explorable digital worlds. He’s even set his sights on actual structures influenced by his photographs: “Now I’m working with an architect to investigate how you might build like the longest-lasting building ever. It’d be like building an art museum that protects the art from humanity.”

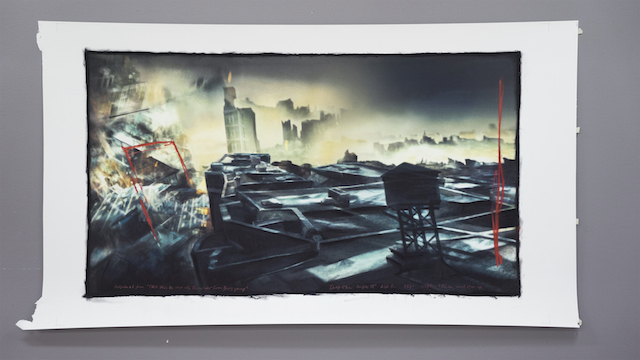

Jacob Fellander, “Just around the Corner,” 2014

Like his very artworks, Felländer’s career path is one that, while perhaps improvised, became something that quickly discovered itself in its own revolution: “If you look at history of mankind, so many inventions have come through mistakes, like leaning a sandwich out of the window, finding mold, and making antibiotics. Or the Post-It: they were trying to make the best glue in the world. […] I try to combine classical mistakes, like multiple exposures and light leaks, to get something else. Compared to when I first started, the perfect image is less interesting. Failure is perfection.”

Undeniably unconventional, Felländer’s practice is just as applicable to life as it is art: dig deep down into the fundamentals of whatever it is you’re doing, and when you think you’ve failed, keep going. There’s a certain magic in the fearless pursuit of the unknown, for its own sake. After all, if an image is just the way light hits a surface, an imperfect surface will always have more character.

Courtesy of Jacob Felländer Studios

Click here to visit Jacob Felländer’s website.

Related:

Sheree Hovsepian’s Decisive Moment | Studio Visits

10,000 Stacked Photos Create Insanely Detailed Insect Portraits