The four damaged reactor buildings in 2011. Image via Wikimedia

The past couple of weeks have seen two stories draw attention back to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of March 2011, in which three nuclear reactors melted down after the plant was hit by a tsunami. Radioactive material was released in what was the biggest and most disastrous nuclear incident since Chernobyl in 1986.

One story concerned some pictures of deformed daisies near the Fukushima Daiichi site, which trended online for a while and got everyone all hot under the collar about radiation, until it was established that they occur all the time in nature. So no need to worry about that.

Videos by VICE

The other was a video released by Arnie Gundersen, a former nuclear industry executive and engineer who’s declared Fukushima “the biggest industrial catastrophe in the history of mankind.” In it, he claimed that 23,000-tankers of water contaminated with radioactive isotopes have leaked into the Pacific from the Fukushima Daiichi site since 2011 and will continue to do so for decades—at a rate of three hundred tons a day. So maybe start worrying again.

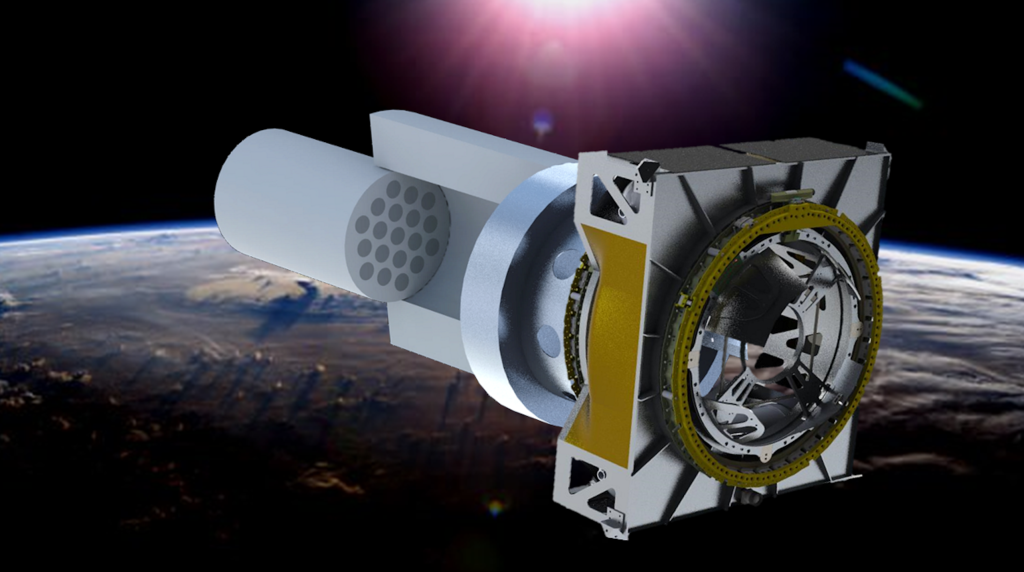

On Motherboard: Scientists Are Using Cosmic Radiation to Peer Inside Fukushima’s Mangled Reactor

Sure enough, a recent report by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) claimed that concentrations of radioactive isotope Strontium-90 have reached record highs in certain areas of the Pacific Ocean around Fukushima, with levels spiking by about 1,000 percent in three months.

What does this mean? Frustratingly, nobody seems to know for sure. Dr. Paul Dorfman of the Energy Institute of UCL says that views differ as to whether these enormous discharges will be diluted by the sea, and if not, where they will go. There are concerns over fishing in the area, as well the potential ways that this contamination can reach humankind—through the eating of those potentially contaminated fish, for example.

Any other reasons to be concerned? Well, if you’re Japanese, you’d do well to be at least suspicious. Because both Gundersen and Dorfman are adamant that the thirty-year decontamination operation of Fukushima Daiichi, which the government is allegedly aiming for, is unfeasible.

We talked to Gunderson to ask him why he thinks the Japanese government is so intent on a cleanup that seems impossible. Gundersen has stated previously that the answer “has nothing to do with science and everything to do with politics and money,” so we asked him about that, too.

VICE: Hi Arnie, thanks for talking to us. You’re saying that it’s the Japanese banks that are pushing for a quick cleanup. Why do you think this is?

Arnie Gundersen: I can’t reveal my sources, but they are very significant diplomats who have told me that the pressure on the Diet (Japanese parliament) from the electric companies is astronomical. The companies that own the plants want to get their money back, but these plants have been shut down for five years and the staff of approximately seven hundred people have been retained; and the taxes have been paid, and the towns that they are in haven’t seen any decline in their economy… even though these plants aren’t generating revenue. So where does the money come from?

The answer is that two or so billion dollars has been lent by banks to keep the utilities afloat, because utilities don’t have two billion dollars in cash sitting around. Now, it’s payback time for the bankers, and between the banks who want their two or three billion back, and the utilities that want their investment—which is probably in the order of $10 or $20 billion—back, then the pressure on the Diet is astronomical. Big money is pushing very hard to get these reactors started back up.

So you say they’ve proposed a 30-year cleanup, and you don’t think this is possible, correct?

No, I’m sure it’s not. A normal, clean power plant takes about ten years to decommission, and by “clean” I mean where literally the workers are working in street clothes most of the time. There are very few places in the plant where they’d have to put on what we call PCs—protective clothing. The white uniforms you see all over Fukushima… I’ve worked in nuclear power plants and only once or twice have had to wear those.

You can literally walk through most power plants in your street clothes, and the reason they have to wear them outside at Fukushima is because the radiation fields are so high. What’s happening now is that the ground is highly radioactive. In some areas where the radiation level is so high they’ve even put steel plates on top of the ground so that people could walk there. That’s not a normal decommissioning.

What does this mean?

It means the level of radiation is so high that my biggest humanitarian concern is that —if the Japanese push to get these plants dismantled quickly—they will burn out hundreds and hundreds of young men. It’s usually young men because that’s how the construction trade is, needlessly. My point is, walk away for a hundred years, then come back in a hundred. By waiting a hundred years you’re reducing the radiation exposure to a significant, young virile gene pool that in my opinion doesn’t deserve to be exposed right now.

So you’re arguing there’s a human cost to the fact that this is being pushed through as fast as possible.

Yes, quite. There’s a very real human cost to thousands of construction workers who are being exposed and will be exposed. But they have to show the Japanese that they’re dismantling that site because if the Japanese don’t believe it can be cleaned up they won’t let the other plants start back up.

It’s a show. This is all about showing the Japanese that it’s not too bad, and we can run our other 40 or so plants fine, trust us. It’s definitely symbolic for the Japanese, but the real reason is the banks want their money back.