TOKYO — The Japanese government has partnered with the country’s most powerful business lobby to do something that, in theory, shouldn’t be that difficult: make people work less and have more fun. And they’re hoping to save lives in the process.

Karoshi, or death by overwork, has been a part of the Japanese lexicon and a legally recognized cause of death since the 1980s. Despite growing awareness, cases of overwork resulting in illness or death continue to rise at a rapid rate. The number of resulting compensation claims reached a record high in financial year 2015, when the government received 2,310 compensation claims for mental illness, brain disease, and heart disease caused by overwork.

Videos by VICE

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also attributed 93 suicides or suicide attempts that year to working excessive hours.

“I sometimes wonder how long we’ll have to do this. We’re all so exhausted.”

Claims of karoshi have more than tripled since the government began tracking them in 1999, when 11 suicides or suicide attempts were officially recognized as being work-related. But experts say the real number of karoshi deaths is much higher and accuse the government of trying to downplay the issue.

To much fanfare both abroad and at home, Japan launched its very first “Premium Friday” in February. The idea is simple: companies are encouraged to let their employees off at 3 p.m. on the last Friday of every month. Worried about the country’s economic slowdown, the government hopes that a bit of extra free time will encourage people to shop more and help in the fight against overwork in the process. But the program has many in Japan wondering if the government is serious about changing the national work culture and improving work-life balance — or simply staging an easy publicity stunt.

The Japanese have reason to be skeptical. In an effort to combat karoshi, the government has introduced overtime regulations, but many companies get around the rules by making employees take their work home or by pressuring them to clock out — and then continue working at the office. This is compounded by a lax labor market in which roughly 40 percent of Japan’s labor force are contract or part-time workers with few legal protections.

Even when workers are entitled to time off, they rarely use it. According to the government, full-time Japanese workers get, on average, 18.4 days of paid leave a year, but most take less than half of that.

The International Labour Organization site lists a few “typical” karoshi cases: a 34-year-old man who died from cardiac arrest after working 110 hours on a weekly basis. A 58-year-old who died of a stroke after working an average of 4,320 hours a year, or 83 hours a week. A 22-year-old nurse who had a fatal heart attack after working 34-hour shifts five times a month.

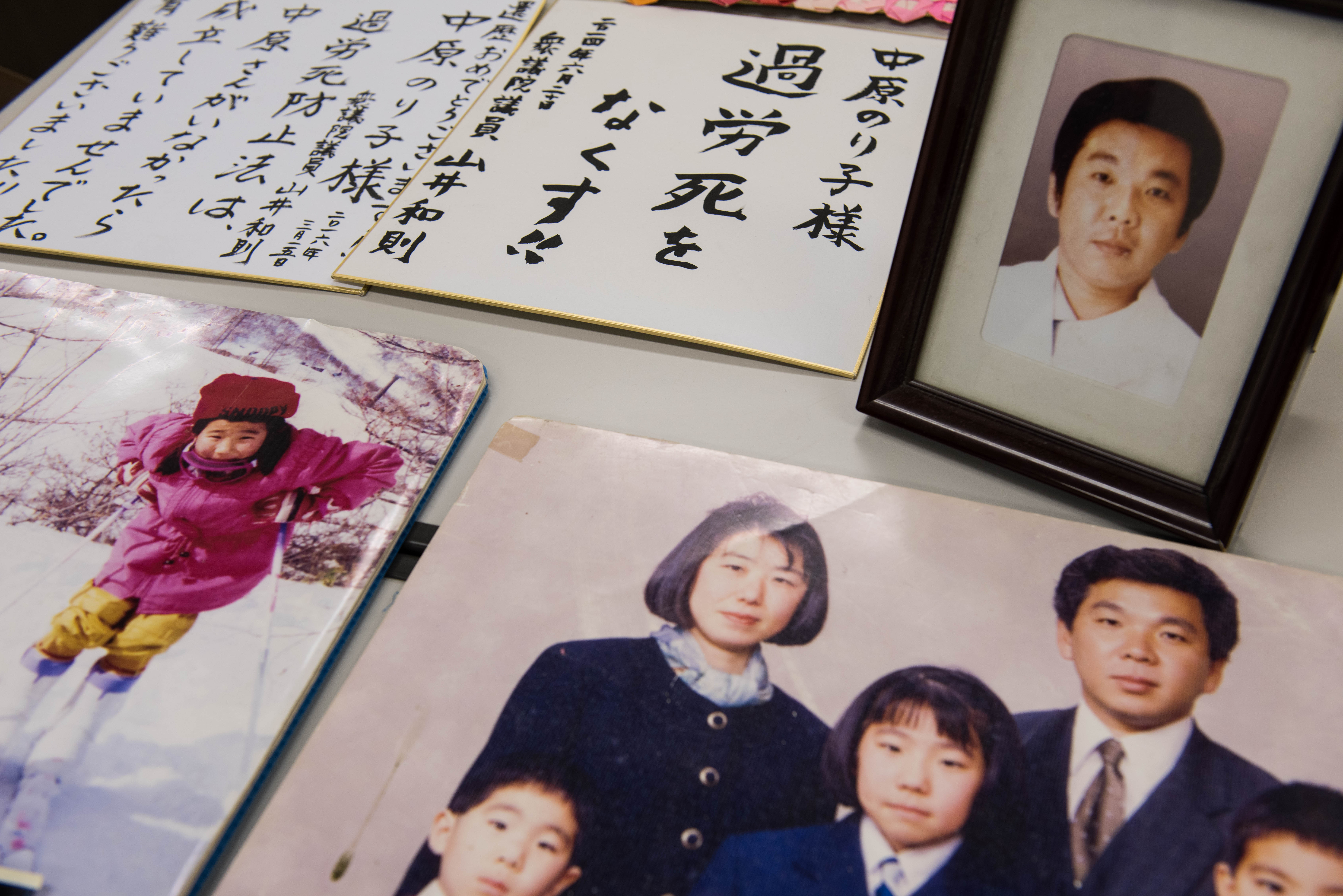

Noriko Nakahara became an advocate for better working conditions after her husband, a pediatrician, killed himself 18 years ago. She had begged him to quit his job, worried that the long hours were wearing him down. But he insisted that being a doctor was his calling and worried that if he quit, the pediatrics department would suffer to the detriment of the entire community.

In 1999, at the age of 44, he jumped to his death from the roof of the hospital where he worked.

“He did not die because of personal issues,” Nakahara said, “but because of a social issue.”

Two years later, she applied for compensation from the government, claiming her husband’s death was job-related. After she was denied, she took the case to court, and in 2007 a judge ruled that his suicide was indeed caused by his workload.

During the court battle, Nakahara’s lawyer advised her to garner public attention by creating a support group. So she joined the National Family Association for Karoshi Awareness and founded its Tokyo chapter. She’s been an active member ever since.

“More and more new members join every year,” she told VICE News.

Over the last year, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has pushed for change in Japan’s problematic labor market — a platform he calls “Work Style Reform.”

Karoshi was traditionally associated with salarymen, as white-collar workers are called in Japan. But recently, work-related suicides have seen a sharp increase in women and young people who make up the majority of Japan’s part-time, freelance, and contract worker force.

“I sometimes wonder how long we’ll have to do this. We’re all so exhausted.”

The number of non-regular workers in Japan has grown steadily over the past 30 years. Harvard historian Andrew Gordon called the increase “the most important shift in Japanese employment.”

These part-time workers are often college students or recent graduates unwilling or unable to get a regular office job, or mothers attempting to re-enter the workforce. Such workers lack job security as well as the benefits that accompany a regular job, like standardized working hours and health insurance. Japanese companies cut costs by hiring part-time work, often having these employees work overnight shifts or on weekends without overtime compensation.

In an attempt to change the current system, Abe’s administration is proposing guidelines and regulations that will enforce equal compensation for equal work, regardless of whether workers are full- or part-time. And to improve work-life balance, the government has proposed capping the number of overtime an employee can work to 100 hours a month.

But lawmakers and advocates worry the proposed regulations are too lax and full of loopholes, and say more is needed to effectively combat Japan’s karoshi problem.

Many worry the current rules don’t fully appreciate the pressure of the “giving face” work culture, which makes leaving the office early or taking time off a particularly stressful affair. Proving your dedication to the company and putting in face-time with colleagues can be seen as more important than actual performance, and the economy reflects that. According to the latest OECD figures on productivity, which are calculated by dividing GDP per capita by the number of hours worked, Japan is the least productive country in the G7; the U.S. is roughly 59 percent more productive.

Nakahara thinks that Premium Friday is a good idea in theory but is skeptical about whether companies are prepared to actually help combat long working hours. She points to Itochu, one of Japan’s largest corporations, which turns off its lights at 10 p.m. to prevent people from working any later at the office. Itochu also encourages employees to come to work early in the morning, providing a free and elaborate breakfast buffet as an incentive.

“We’re not learning anything,” Nakahara said. “That’s why we make laws and keep fighting. I sometimes wonder how long we’ll have to do this. We’re all so exhausted. But I hope the people of Japan, and the government, promise to protect our workers and make things better.”

Dexter Thomas contributed reporting to this story.