Before virtual reality and augmented reality were common, way back in the 50s and 60s, West Coast artist Stan VanDerBeek was breaking ground in immersive experiences with expanded cinema, video, and computer art. His Movie-Drome, with its multiple projections on the inside of a dome, took the idea of cinema and made it into a 360-degree experience of immersive audio and visuals. In a new exhibition at Sprüth Magers Los Angeles, VanDerBeek (who passed away in 1984) is paired with artist Jon Rafman, a modern maker of immersive, expanded realities.

“A starting point of the show was to imagine a time where digital devices, animation and virtual worlds are constant presences,” the show’s curator Johannes Fricke Waldthausen tells The Creators Project. “[Presences with] impact on our identity and how we navigate our lives and our feelings of how we relate to each other.”

Videos by VICE

Stan VanDerBeek, Movie Mural, 1968,2016-17. Courtesy The Stan VanDerBeek Estate, Sprüth Magers and the Box. Photo, Andrew V. Uroskie

In the exhibition, two figures in the history of immersive media collide. Viewers see how a sense of poetry—often dark, satirical, and occasionally dystopian—finds its way into Rafman’s current and VanDerBeek’s past animated realities. The works on display include 14 framed collage pieces on billboard paper, featuring pastels and watercolors. VanDerBeek’s choice of substrate likely had something to do with Marshall McLuhan’s idea of how printed media (and electronic media like television) impacted individual and collective reality.

“Instagram’s imagery and mood is very virtual, very simulated,” says Waldthausen of VanDerBeek’s framed pieces. “The stills from the works in the show look like Instagram images, like perfected renderings. So it is these two adjunct worlds that do really matter; the digital and screen on the one hand, and our feelings, body-perception and truly creative, human qualities on the other.”

Installation View. Stan VanDerBeek. Photo Robert Wedemeyer Courtesy Sprüth Magers

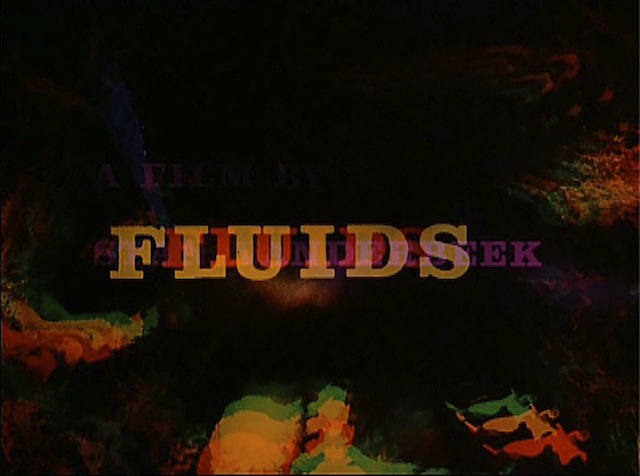

Another wall features projections of three of VanDerBeek’s 16mm films, here projected in video—Oh!, Astral Man, and Fluids. These animated works feature collage, paints, and psychotropic substances, all designed to draw the viewer into VanDerBeek’s media-saturated simulated realities.

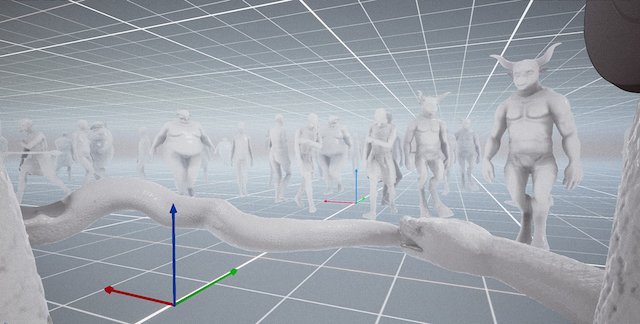

Rafman’s work, also animated and stuffed with various media, shows just how far the sense of immersion has come since the mid-20th century. It also shows how computer-generated animation, which VanDerBeek was interested in, is taking us closer and closer to the uncanny valley.

“I think like anyone what I consumed growing up had a huge influence on me as an individual,” says Rafman. “I played quite a lot of video games and read a lot of science fiction, and I think I pull a lot from those early childhood feelings and profound experiences.”

Jon Rafman, Poor Magic (Detail)

“There is so much capital invested in video games and they’re a big product with so many subtleties, like a sense of lighting with the way it dapples across the grass or leaves,” he adds. “I think that this is a type of mise-en-scène that doesn’t really exist in Hollywood films anymore.”

Rafman searches for images, video clips, and comments on everything from YouTube to Reddit, taking screenshots here and there, but never recording his sources. Some of these materials make their way into his work, while others merely serve as conceptual inspiration. Rafman likes the idea of not remembering where things came from, and also not knowing how it will all ultimately connect.

Installation view of Jon Rafman’s ‘Transdimensional Serpent’

For his new piece, Poor Magic, which is debuting at the exhibition, Rafman used one such found quote in a mesmerizing way. As the video’s opening frames unfold with bluish skeletons moving on a black void, a voice intones atop dark electronic drones, “If you can’t sleep at night it means you’re awake in someone else’s dream.” This quote, which Rafman says is either an ancient Chinese proverb or inspirational meme found on Tumblr, introduces the idea that virtual realities, simulations, and other immersive experiences are akin to dream states.

“The idea for Poor Magic came from imagining almost the worst possible or most distressing scenario of what would happen if the singularity was achieved,” he adds. “For me that would be a world in which we’re all uploaded, where no one can die anymore, and we’re all avatars in a virtual simulation with a computer AI that is infinitely intelligent and controls us forever and ever. So, it’s kind of like a nightmare you can’t wake up from.”

Jon Rafman, Poor Magic (Detail)

Rafman finds shades of this nightmare in our everyday reality. Some might experience it as constant psychological suffering, while others might experience it as a political ideology from which there seems no escape.

Rafman’s other works in the exhibition, Open Heart Warrior and Transdimensional Serpent, feature a similar digital darkness. In Open Heart Warrior, scenes of natural splendor are paired with gruesome human realities of imprisonment and death. And in Transdimensional Serpent, Rafman uses an Oculus Rift to take viewers into a virtual reality experience that defies time and space, with results that are both beautiful and disturbing.

Stan VanDerBeek, Untitled, 1978-83

True, VanDerBeek and Rafman are separated as much by time as by the technology and media they used. But their works show a similar interest in how technology warps reality.

“Today we are surrounded by simulated, animated worlds—we are within them and they are in us, like a dream-state or a non-linear, infinite library, as Jorge Luis Borges would put it,” says Waldthausen. “An automatic world, where the body, the senses and technology are more closely united than ever before. This is only the beginning of A.I. and augmented reality.”

Jon Rafman, Transdimensional Serpent (Detail), 2016. C. Jon Rafman. Courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers

Stan VanDerBeek, Fluids (Film Still), 1964. C. The Stan VanDerBeek Estate, Courtesy the Stan VanDerBeek Estatee, Sprüth Magers and the Box

Jon Rafman / Stan VanDerBeek runs through March 4 at Sprüth Magers Los Angeles.

Related:

How to See Stuxnet? ‘Zero Days’ Filmmakers Find an Unlikely Answer in VR

More

From VICE

-

(Photo via MBARI / YouTube) -

(Photo by BRYAN R. SMITH/AFP via Getty Images) -

Screenshot: Infold Games -

Screenshot: Studio Trigger