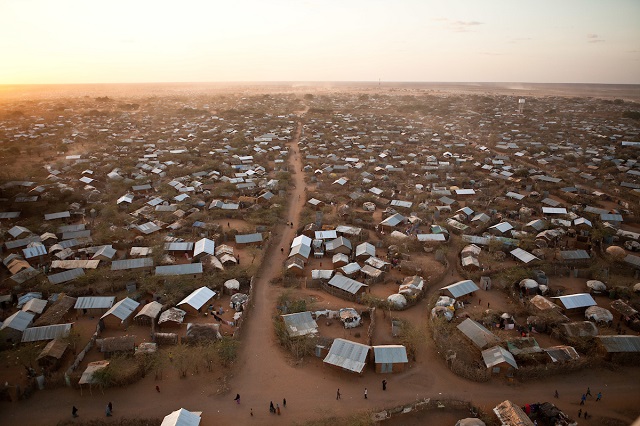

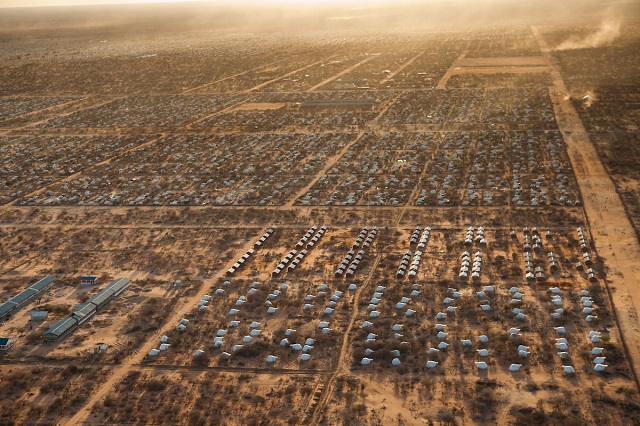

Shot high above the sunburnt ground, aerial images capture the order and the immensity of the biggest refugee camp in the world: Dadaab, Kenya. Photographer Brendan Bannon’s series of images from high above is featured in part of an ongoing group exhibition at the MoMA, whose title, Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter, just happens to describe equally well the narrative arch of the past ten years of Bannon’s career.

The photographer first went to Africa in 2006 to teach photography and writing to the children affected by HIV/AIDS in Busia, Uganda. This experience led Bannon to found The Most Important Picture, an organization that facilitates photography workshops for children to give “voice to the voiceless.” Bannon currently conducts these workshops at the Za’atari Refugee Camp in Jordan, where he and his organization started the Do You See What I See project, which gives young Syrian refugees a chance to tell their own stories through photography.

Videos by VICE

Bannon has also spent the last decade obsessively documenting the plight of refugees. It is an issue he feels a personal draw to. As a girl, his mother fled with her family from their home in Ukraine to escape Stalin’s violent purges. “I grew up on stories of [my mother and her family] traveling across Europe in a horse drawn wagon,” Bannon tells The Creators Project. “Something about those stories, the genesis of my family, made me interested in what refugees go through and what happens after they escape the wars they flee.”

October 2011. Brendan Bannon/IOM/UNHCR

In 2006, this interest led Bannon straight to the heart of the matter, otherwise known as Dadaab. It was his first trip to Africa and he had been hired by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) to photograph a flood that had engulfed the desert camp. “It was supposed to be a day job,” Bannon says, “flying up and back from Nairobi, but the situation worsened and I decided to stay and keep photographing.” Houses, business, schools, and roads were destroyed under 3 to 4 feet of water and he was often wading through water that was chest deep, he describes. “I spent the next week walking through the camp with residents visiting homes, hearing stories, and making pictures.”

In 2011, Bannon returned to the camp under entirely opposite circumstances. A drought and a massive influx of refugees prompted groups like UNHCR, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders, or MSF) to redouble their efforts in Dadaab. Bannon worked with all three of these organizations, striving to “tell the story of the people arriving by the thousands.”

October, 2011. Brendan Bannon/IOM/UNHCR

The photographer ended up cramped together with a videographer inside a Cessna, its passenger door removed, soaring above Dadaab’s arid plain. “The camp is vast and it is so hard to get a sense of scale,” says Bannon. “Even in the pictures I made you can barely tell how big it is.” At the time of photographing, there were five main settlements in the camps housing around 500,000 people. And while Bannon’s photographs can only capture one or two of the sections of the camp, they nonetheless give viewers a unique vantage point.

“You get a sense of the scale of the place: it is massive, a series of interconnected towns settled by refugees and inhabited by hundreds of thousands of people for the last 25 years.”

“I loved seeing the paths that were made by people and livestock when I flew over,” Bannon continues. “Seeing the way the land was inhabited and organized and utilized was incredible. You see examples [of this] when you’re walking around but you don’t get the sense of time. The wear marks in the sand that only happened over generations of use tell another layer of the story.”

He recognizes, however, that the aerial images can only tell so much of the story of the thousands of lives below him. “Something aerial shows is the organization and longevity of the place,” he says. “Being on the ground among people gives you a chance to understand individual stories and there are hundreds of thousands of individual stories in a place like Dadaab.” His complementary series on Dadaab, shot during the same period, does just this: it contrasts the detached spectacle of the camp from above with up-close and personal images of the lives of refugees, mostly Somali refugees, on the ground.

October, 2011. Brendan Bannon/IOM/UNHCR

Even these images, however, give but a fleeting glimpse. “The biggest challenge in telling stories of people in crisis is that you are meeting people at the worst moment of their lives,” Bannon says. “You have very little time to delve into the stories of who they were before the crisis and almost no time to understand the depth of the experiences they are living through. If you manage to do a good job, the chances that you’ll have avenue to tell the stories with the depth they warrant is slim. So it can feel like a betrayal to ask someone’s trust and then only be able to tell a small part of what they share with you.”

“The inability to change the situation for people is also frustrating and upsetting,” he adds. “I often remind myself that the most important thing in the moment of reporting is to listen, really listen to what you are being told. If you can’t be present you shouldn’t be there.”

October, 2011. Brendan Bannon/IOM/UNHCR

Despite their limitations, for many of us, images like Bannon’s and those of his fellow artists in the MoMA exhibition are some of the few resources we have to attempt to come to a better understanding of the lives of refugees. And Bannon recognizes this. “Any exhibition, picture, poem, film, interview, article that treats the refugee situation as a complex multidimensional and human situation is important,” he says. “We live in a moment when serious thought and even compassion are trivialized. Exhibits like the one at the MoMA seek to elevate the conversation and create a basis of knowledge and thought so we can understand and react intelligently and with awareness.”

And what does the photographer think are the consequences of trivializing the refugee situation? “In the current moment there seems to be little understanding of refugees in the United States,” he observes. “It is precisely because of the overwhelming ignorance of refugee realities that refugees have been so readily made pawns, scapegoats, and boogeymen in our current election and politics. Refugees, immigrants, and asylum seekers are all lumped together in one pot by politicians and press. When there is an absence of basic understanding it is incredibly easy to manipulate people’s’ emotions.”

October, 2011. Brendan Bannon/IOM/UNHCR

“When people hear individual stories they are often moved to empathy,” he adds. “Before this year’s election I usually saw and empathetic response to the tragedies of refugee life. Now there is much more veniality and anxiety. It’s a pity that there is so much fear directed at people who have already lost so much. These refugees are the victims not the perpetrators.”

October, 2011. Brendan Bannon/IOM/UNHCR

Find more of Bannon’s incredible images on his website. Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter is on at the MoMA until January 22, 2017.

Related:

Virtual Reality Journalism Puts You Inside the Refugee Crisis