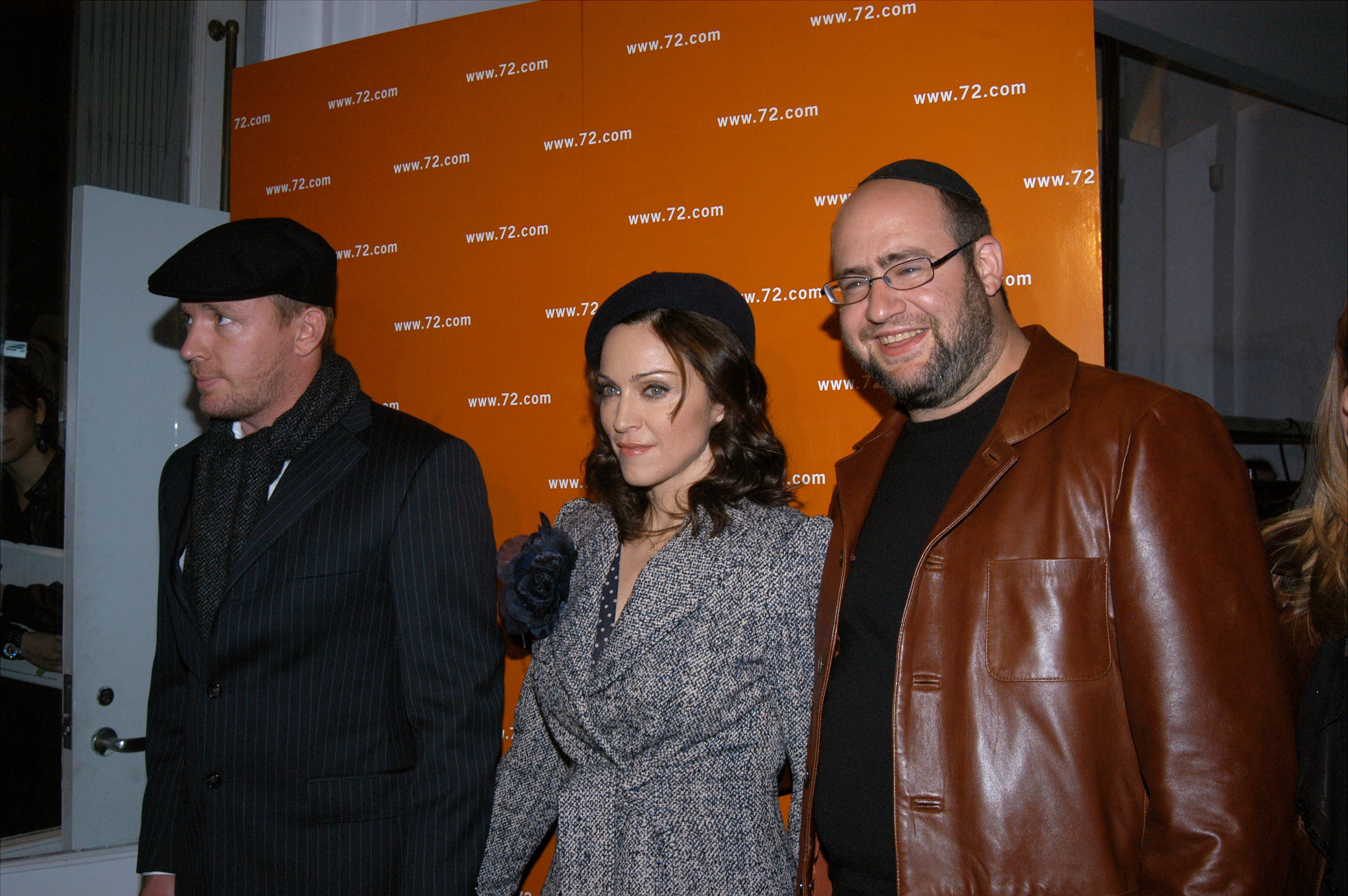

Yehuda Berg doesn’t exactly have anything to sell these days—except, perhaps, the concept of his own redemption. On a weekday afternoon in October, the former co-director of the glitzy Kabbalah Centre—best known as the spiritual organization of choice in the mid-2000s for stars like Madonna, Roseanne Barr, Ashton Kutcher and Demi Moore—was on the phone from his office in Los Angeles, making his way tentatively through one of his first interviews in six years, after a particularly precipitous self-inflicted fall from grace. He’d decided, he explained, that his calling in life is to be a leader in something that sounds like addiction recovery mixed with crisis management.

“I’m in the process of figuring out a process for people who have hit bottom and want a second chance,” he said. In the next few weeks to months, he added, he was “going to put together some talks, to get people into recovery who don’t know they need to get there, or people who have burnt out, who have fallen, who want a second chance.”

Videos by VICE

Among those people is Berg himself. As everyone on the phone—me, Berg, and a watchful but mostly silent public relations minder—was highly aware, in 2014, Berg was sued in civil court in California by a former Kabbalah Centre student named Jena Scaccetti, who charged that he’d pressured her to take Vicodin; forcibly groped her as she struggled; tried to persuade her to have sex with him; scrolled through her phone while making lewd, invasive comments about her photos; and threatened to “fucking kill” her if she told anyone. A civil jury ultimately did not find Berg liable for sexual battery, but did find that he’d inflicted emotional distress on Scaccetti. Berg was ordered to pay her $135,000 in compensatory and punitive damages, while the Kabbalah Centre was ordered to pay $42,500, a judgment that was affirmed on appeal in 2018. Berg testified during the trial that he was addicted to alcohol and drugs during the time he had known Scaccetti.

This is not history that Berg is eager to revisit, though he did talk openly about struggling with addiction and entering a recovery program. During the process of getting sober, Berg said, he’d also come to the painful realization that he’d been sexually abused as a child by two different family acquaintances, one a babysitter and one an older neighborhood boy.

“It doesn’t make anything else in the future okay,” he said. “It just gives it context. When there’s pain deep inside, and you don’t even know where the pain is coming from, you have to let it out and see what’s underneath.”

These are hard-won and commendable realizations, but it seems safe to say Berg is hoping that, with time as a convenient balm, other people will become less interested in discussing things he prefers not to. Before our interview began, his public relations representative, John Rarrick of the agency York and Chapel, lightly suggested I not dwell on “the past.”

“Yehuda’s happy to talk about the past and anything easily Google-able,” he said, “but much more interested in talking about the present and the future.”

As we made our way through a stilted conversation about Berg’s vague business ideas—he originally hoped to start a residential rehab facility, he explained, plans which fell through twice—it was hard not to think that he has chosen precisely the wrong moment for his comeback.

Our call had its origins in an unsolicited email from Berg’s PR agency inviting VICE to interview him. (“Those 2014 sensational headlines only tell one part of his story,” it read, in part. It also promised he had “taken accountability for his actions, set new goals, and developed the strength to give himself and others a second chance.”)

The email led, within a few short minutes on Google, to federal court records showing that Berg, his brother Michael, his mother Karen, the Kabbalah Centre itself, and a constellation of related entities are the defendants in an explosive civil lawsuit first filed in New York in July 2019 by seven core former Kabbalah devotees. The plaintiffs were part of a group of special spiritual workers within the organization known as “chevre.”

(The Kabbalah Centre and their lawyers did not respond to multiple requests for comment from VICE about the lawsuit or other elements of this story. Court records show they filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit on November 25, and plan to ask the court to force five of the plaintiffs to settle their claims in arbitration proceedings, saying the former chevre signed agreements long ago stating they would settle any legal claims against the organization that way.)

The suit lays bare several long-running controversies at the Centre. Members of the previous chevre—one of whom once served as a spokesperson for the Centre—accuse the organization of being little more than a personal enrichment scheme for the Bergs themselves. The plaintiffs, the suit claims, were led to believe “that they would be spiritual workers who were to help enlighten humanity to the teachings of the Kabbalah. In reality, the individuals who control the Centre–the Bergs–“operate a cult that preys upon those seeking to improve the world through the performance of good works.” It also claims that the Centre’s “ultimate objective” is “to raise revenue and solicit donations that benefit the Individual Defendants and their families.”

The suit paints a portrait of the Centre as an organization that looks, in some ways, strikingly similar to how Scientology is said to operate, with a core set of rigorously dedicated staffers who set to work ferreting out both potential students’ weaknesses and their financials. The former chevre allege that they were instructed to engage in a “sophisticated marketing operation, learning intimate details about students’ lives in order to target particular students for particular donation requests.” The suit asks for damages and unpaid minimum wages, overtime wages, and “statutory and civil penalties.”

Meanwhile, several students who left the Kabbalah Centre in the last few years—people who are not plaintiffs in the lawsuit—told VICE they had been pressured for monetary donations that sometimes greatly exceeded what they were actually able to pay, and were made to feel deeply guilty and even spiritually imperiled when they refused.

The plaintiffs accuse Berg himself of remaining secretly involved in the Centre for years after his supposed resignation in 2014, writing that he continued to have “deep and ongoing involvement in Centre decisions and operations, even if the Centre no longer publicly acknowledges his involvement.” If true, that would severely compromise his claims to have been humbly working on his sobriety for the last several years before finally returning, reluctantly, to the spotlight.

Berg denied he has had any continued involvement with the Centre. “I don’t like to talk about pending litigation,” he said, “but I resigned on May 1, 2014 and that’s about it.”

His mother and brother remain key figures at the Centre, and his wife Michal works for Spirituality for Kids, a nonprofit that was previously an offshoot of the Kabbalah Centre before becoming its own legal entity in 2008. He said that his relationship with the Kabbalah Centre today is limited, and centered around his family. “If there’s a religious gathering, I’ll go because my mom is there or my brother is there,” he said. “I have family who are still members. But I don’t consider myself a practicing member of Kabbalah.” He also said he has no insight into the Centre’s current activities: “I don’t come to any events. I don’t have a handle or any idea of what their plans are or how they’re doing.”

Berg told me that he was, admittedly, returning to the spotlight in a bid to find work. “I’m hoping this will be my full-time job,” he said. But he also said his return comes from a pure place. “My entire life, I was in the ‘helping people’ business, whatever you want to call it,” he said. “And I’ve always felt close to people, always felt open and connected. And now I can do it right. I can do it right.”

Berg doesn’t link his personal failings with the Kabbalah Centre’s larger controversies. But the fact is that the two are inextricably tied. And at the moment of his inopportune bid for self-redemption, many people are interested in discussing just that.

For decades, the Kabbalah Centre’s leading figure was Phillip Berg, Yehuda’s father, whom Kabbalah Centre students referred to as “the Rav,” and who became the Centre’s director in 1969. He led the organization until his death in 2013; today, his wife Karen serves in his stead, acting as the spiritual leader of the organization and its most prominent public face. Their two children, Yehuda and his brother Michael, were among the star teachers of the organization until Yehuda’s downfall; Michael remains a leading teacher there, as does his wife Monica. (In their obituary of Philip Berg, the Los Angeles Times pointed out that Berg “was sued for plagiarizing another kabbalah scholar, and Orthodox leaders publicly condemned him as a fraud.”)

The precepts of the Centre are, at this point, fairly well-known: It promises to bring the wisdom of the Kabbalah, a system of Jewish mystical thought, and the Zohar, its central text, to the masses. Various schools of Kabbalistic thought have been around within Judaism since the 12th or 13th century, when the first version of the Zohar first appeared in Spain.

Kabbalah study is a dense and often unwieldy discipline, usually only studied by advanced Jewish scholars. The Kabbalah Centre’s twist was deciding that the information contained within Kabbalah could be powerful for more ordinary seekers who didn’t have the benefit of years of study or even any particular knowledge of Judaism. The Centre generally describes itself publicly as a spiritual, rather than a religious, organization, dedicated to increasing the amount of “Light”—a kind of divinely-backed energy—within each person and in the world.

Indeed, the Centre teaches that one doesn’t even need to read the Zohar in order to imbue oneself with its power.

“To merely pick up the Zohar, to scan its Aramaic letters and allow in the energy that infuses them, is to experience what kabbalists have experienced for thousands of years,” the Centre’s website promises, “a powerful energy-giving instrument, a life-saving tool imbued with the ability to bring peace, protection, healing and fulfillment to those who possess it.” The Centre also employs astrology alongside Jewish mysticism, providing both daily and weekly astrology forecasts, many of them written by Yael Yardeni, a head teacher. In her blog posts and video addresses on the site, Karen Berg also makes frequent reference to astrological principles. (The Jewish year is governed by a lunar calendar, but there is debate within branches of Orthodox Judaism about whether astrology is a permissible pastime for observant Jews.)

Then, of course, there are the products. The Centre sells “Kabbalah Water,” which ex-students told us the Centre implies can, when consumed, further increase Light; it also sells Pinchas Water, which is both more expensive and, as they have told followers, more spiritually powerful. The Kabbalah Water runs $30 for a 1-liter case on the Kabbalah Centre website, while Pinchas Water will set you back $52. (In 2005, the head of the Kabbalah Centre in Tel Aviv was arrested on suspicion of defrauding a cancer patient named Leah Zonis, whose husband Boris said she’d been encouraged to donate thousands of dollars, which would supposedly aid in her recovery. The Guardian reported at the time that she was also told that she “could increase her chances of recovery by drinking branded water.” Zonis died in August of that year. The case was closed in 2006 when Boris Zonis decided to drop the charges, Religion News reports. Zonis declined for comment when reached by VICE, writing, “I want to forget this issue and this case about Leah (ז”ל). It makes me very very very sad.”)

There’s also a variety of candles ( $19.99) and a sage smudge stick ($26). And then of course there are the red string bracelets that were the accessory de rigeur of the A-list, spiritually evolved celebrity of the mid-aughts. These, the Centre says, offer protection against the evil eye. They are also $26. One more mainstream institution for Kabbalah study issued a pointed article a few years ago entitled “Myths About Kabbalah,” writing, in part, that “Red strings, holy water and other products are a lucrative commercial invention created in the past two decades.”

“If you walk in the door in New York, in L.A., there’s great emphasis on any new books they have,” said Lewis De Payne. He became a Kabbalah Centre follower about seven years ago, brought in by his then-wife, and remained involved until two years ago. “During any event you can increase the Light you receive by buying Kabbalah water and drinking it during the event and taking some home.” (The Times of London reported in 2006 that Madonna also promoted Kabbalah water as a possible way to neutralize nuclear waste in a Ukranian lake.)

De Payne found himself confused by some of the spiritual math involved in the products on offer. “Kabbalah Water has an energy level of seven but the more expensive, Pinchas Water, has one of 10,” he said. “But how do you achieve that difference in units?”

Questions like this, he says, were ultimately part of what caused him to leave the Centre.

The business model has been a lucrative and successful one, by all accounts. The Centre says it has 50 locations worldwide. But it’s difficult to get a truly comprehensive picture of what the Kabbalah Centre’s finances look like, because they’re a religious 501c3 nonprofit. That means they don’t have to file a Form 990. That’s the form that all other secular nonprofits give to the IRS, which would make a good portion of their financial information public, including how much board members are compensated, how their money is allocated, and its net assets and liabilities. (That kind of privacy and financial benefits are prized by some religious nonprofits, like Scientology, which by its own admission spent some 40 years battling the IRS for that designation. Enormously wealthy televangelists like Joel Osteen have also managed to secure 501c3 status, which has been controversial.) Religious organizations are also much harder to sue.

In 2009, though, a former chief financial officer for the company told the New York Post that the Centre held an estimated “$200 million in real estate assets, $60 million in annual revenue and a $60 million investment fund.” Around the same time, Yehuda Berg was becoming a minor celebrity in his own right, included on the “most influential rabbis” list published by Newsweek, which called him “the world’s leading authority on the Kabbalah movement.” He also wrote several books, including one in 2006 called The Kabbalah Book of Sex: And Other Mysteries of the Universe. It holds, among other things, that female masturbation is more spiritually permissible than male. It also contains a lengthy passage on the effects of sexual abuse, likening it to “scar tissue” that continues to “affect and influence behavior in various ways.”

For years, celebrities were also famously attracted to the Kabbalah Centre, though that particular spiritual fervor seems to have died down. Madonna is reportedly still very much affiliated with the Centre, but she is about the only A-lister readily associated with the group. (Numerous celebrities didn’t respond to requests for comment about whether they were still affiliated with the Kabbalah Centre today; only Ashton Kutcher’s rep responded, with a terse “No.”) Donna Karan is one of the highest-profile devotees who’s reported to have recently left; her reps did not respond.

A recent Business Insider story, though, revealed that even as the celebrity halo around the Kabbalah Centre waned somewhat, they still managed to make friends in high places, some of them in the tech industry. The site reported that before WeWork’s recent, flaming collapse, Kabbalah Centre higher-ups were deeply involved with the founding and growth of the company, since WeWork CEO Adam Neumann and his wife were Kabbalah Centre devotees.

Business Insider was also the first news outlet to report in any depth on the ex-chevre lawsuit. Star power, and its attendant cash infusions, might have made “Kabbalah” a household word, but they weren’t the real keys to growth. None of it would have been possible without the chevre, who sign vows of poverty and pledge to give their lives to the Centre, acting as teachers, administrative assistants, and more. In court documents, the Centre has argued they are “not dissimilar to monks and nuns” in other religious traditions.

But the new lawsuit claims the chevre were mistreated and exploited in multiple ways.

“The Centre told many chevre, including some Plaintiffs, that to commit themselves fully to the Centre, they had to abandon all their personal possessions and property,” the suit claims. “The property that Plaintiffs and others had was often ‘donated’ to the Centre. This includes real estate, furniture, and savings accounts. The chevre believed they were working all for one and one for all towards a future where the Centre would meet all of their needs, including housing, food, and clothing, forever.”

The former chevre allege they were moved around to different Centre locations, living in often substandard housing: “The Centre could move chevre to a different location–sometimes across the country or around the world–at a moment’s notice. Centre-owned housing was often cramped and run-down.” They allege a “typical arrangement” could include up to a dozen people in a cramped apartment, some of them sleeping in the living room and kitchen.

The Centre also controlled what they ate, the plaintiffs allege, including serving them meals that they were “required to eat,” regardless of whether they contained ingredients that would sicken people with food allergies or sensitivities. “Some chevre also were instructed to apply for food stamps in order to supplement the limited meals the Centre provided,” the suit claims.

The plaintiffs also say they were only allowed to leave the Centre with permission, and even then, getting around was difficult, given that most of them lacked transportation. And medical care, they allege “was nonexistent. Though Defendants promised to take care of chevre for the rest of their lives, chevre with medical or dental needs were suddenly on their own. Because they lacked resources, these chevre often had to find a willing student to pick up the bill. In the case of an emergency, chevre were instructed to go to the hospital, but to provide a false name and address so that Defendants would not be billed.”

The chevre say they were also subjected to punishment if they failed to adequately participate in what the suit calls “the Centre’s quest for ever-increasing revenue and donations.”

“A chevre who raised insufficient funds might be sent to a Centre location where he knew no one,” the suit claims. “He might be excluded from Centre activities. And he would be denied permission to date or to marry.”

The plaintiffs also say they were forced to ask permission if they wanted to see their families, and sometimes had to ask for donations to pay for their travel. They were also, they say, subjected to extreme psychological pressure to remain devoted to the Centre, and, when they faltered, were given lectures about the mysterious and awful fates that befell previous devotees who fell away from the cause.

“Many chevre were told that [Karen] Berg could ‘do magic,’” the suit asserts, “and had an ability to make such things happen to people who ‘betrayed’ her.”

For chevre, particularly young ones, the organization soon started to embody their whole world, one ex-chevre told VICE. (She requested anonymity to protect her privacy, and because she did not want to her name to be asociated with the Bergs.) Approval from the Bergs could feel all-important. That could, she said, create bizarre situations, and ones that crossed both ethical and sexual boundaries, and led her into a situation with Yehuda that she found deeply troubling.

The ex-chevre said that she came from Israel in 1998 to study at the New York Kabbalah Centre.

“It gave me a lot of answers,” she said. “I felt an urge from the inside to be more committed.” She was 26 at the time and dealing with a serious eating disorder—something she told the Bergs, she said.

In 2000, she joined the chevre, where she said she was paid $30 a week and $35 on the new moon. “We were living in this townhouse in Queens,” she said. “It’s like a family home and we had two full families there and then probably 15 girls living there, if not more. We were sharing rooms, no privacy whatsoever.”

Chevre messaged each other on an early chat system called ICQ, and, the ex-chevre said she soon began receiving messages from Yehuda Berg, which she found both flattering and confusing.

“I confided my secrets in him,” she said. “He was their son and in my eyes really someone who could help me.”

Over time, the ex-chevre said, Berg started to ask her more and more personal questions, which soon became questions of a sexual nature. “He was asking me about my sex life,” she said. “It was a rollercoaster. I don’t know how to explain it.” She started staying up very late to talk to him, getting up early to assume her duties, and living in what she describes as a subtly altered state: “It was like I was on a higher voltage. I couldn’t understand, really, what was going on.” Berg never acknowledged her in person, she said, when they saw her at the Centre, only by chat. (Berg declined to respond to the woman’s specific allegations or even confirm if he recalls the incident as described.)

Over time, the woman said, Berg convinced her that they should meet up, and they agreed to do so in an office at the Centre late at night.

“I knew something was wrong but I was still there,” she said recently. “I felt no sexual interest. I clearly remember, my mind couldn’t even go there. It wasn’t something like that. On a romantic level, I can tell you, I felt like, it could be. I didn’t feel like I was in love with him, but I felt a connection and that he cares about me. And at that time, it was very valuable in my eyes. Of course it was an illusion.”

But the first time they met in the office, the woman said, Berg quickly claimed he felt sick to his stomach and needed to leave. The woman said she felt dirty, as though she’d done something wrong, “like I brought him to this situation.”

The second time they agreed to meet, she said, she arrived to find not Berg but an older teacher, who said he’d read their chats and blamed her for creating a sexually charged situation. “I was the one to blame for everything,” she said. “Everyone blamed me.” The older teacher, she remembers, scolded her in part by asking, “Don’t you want to ever get married?”

After Shabbat ended, the woman remembers, she was hauled in to talk to Karen Berg about her supposed misdeeds. “She looked like a mess. That’s all I remember,” the woman said. (Karen Berg did not respond to emails to two of her email addresses requesting comment on this or other aspects of this story.)

The woman later learned, she said, that following the revelation that she’d been messaging with Yehuda, Karen Berg had asked another teacher in Miami to take the woman, meaning she’d be moved to work at the Centre in Florida and pose no more issues for the New York organization. That didn’t happen, the woman said, but she went through periods of shunning from other chevre when she expressed a desire to leave.

She ultimately stayed, eventually moving to a Kabbalah Centre location in another city. Her eating disorder did not improve, she said, and she finally came to realize that she didn’t have the support she needed to recover. In 2004, when family members came to visit her, she told them she was leaving with them.

“I took all my bags,” she said, and left both quickly and quietly. “Nobody knew, nobody saw me.” She felt that if she left openly she would’ve faced extreme pressure to stay and shunning, as she says had happened each time she’d previously said she wanted to leave.

For much of her time, the woman said, she was also afraid to leave, afraid that the spiritual protection the Centre afforded her would be withdrawn, leaving her to the ravages of the world. (According to the new lawsuit from the ex-chevre, when one plaintiff, Jake Stone, left the Centre, “he spent the day vomiting because his fear of living outside of the Centre was so intense.”)

“At one point, the only thought I had in my mind was, ‘What will I drink?,’” she said, if not the spiritually pure Kabbalah Water. “If you don’t have the protection, you would die.”

“It’s a brainwashing system,” she said. “You’re afraid to leave because if you leave you will not be blessed. Every student feels the same. It’s like they teach you this is the blessing, it’s here. The Kabbalah Centre is the holy temple.”

The new lawsuit is not the first time chevre have spoken publicly about alleged mistreatment, or the first time the Kabbalah Centre has been accused of misuse of funds. In 2012, a group of chevre told the New York Post that the Berg family used them as “personal servants” and accused them of “immigration and Medicaid fraud.” (Those former chevre appear to have never brought any kind of legal action against the Centre, and no one there has ever been charged with immigration or Medicaid fraud. The Centre did not respond to interview requests at the time, per the Post.) And in 2013, two wealthy former Kabbalah students sued the Centre, saying their large donations had been misappropriated, and that together they’d given about $1 million for the construction of a new Centre in San Diego, which was never built, and a children’s charity which abruptly ceased operations. (That suit was filed by the same attorney, Alain Bonavida, who sued on Jena Scaccetti’s behalf the following year. The Kabbalah Centre and the Bergs didn’t respond to a request for comment from the Los Angeles Times at the time.) Court documents show that the Kabbalah Centre successfully moved to dismiss most of the case filed by plaintiffs Carolyn Cohen and Randi and Charles Wax, though the argument over a specific donation Cohen made to Spirituality for Kids was returned in May to a lower court. The Centre successfully argued that the plaintiffs couldn’t prove they’d earmarked their donations only for the construction of a new Centre. (In response to a request for comment, one of the plaintiffs, Randi Wax, responded, ”I gave donations with the understanding they would be used to build a Kabbalah Centre in San Diego and the building was never built. When we asked for the money to be returned they refused.”)

Those accusations came at an already tumultuous time for the organization. In 2011, the Los Angeles Times reported that the Centre was being investigated as part of a tax evasion probe “looking into whether nonprofit funds were used for the personal enrichment of the Berg family.”

The probe was, as New York reported, part of the messy aftermath that occurred when Madonna, Kabbalah’s most famous adherent, founded a Centre-backed nonprofit called Raising Malawi that was meant to open a sleek, $15 million girls’ school in the country. In March of 2011, an audit revealed that while $2.4 million of donations had somehow been spent, construction hadn’t ever begun on the school. Raising Malawi confirmed that plans for said school had been scrapped altogether.

The probe, per the L.A. Times, involved both the IRS’s criminal division and the U.S. Attorney’s office in New York’s Southern district. In a statement to the L.A. Times, the Kabbalah Centre acknowledged that they had, as they put it, “received subpoenas from the government concerning tax-related issues, adding, “The Centre and [Spirituality for Kids] intend to work closely with the IRS and the government, and are in the process of providing responsive information to the subpoenas.”

The probe’s findings were never actually announced, and no one involved with the Kabbalah Centre has ever been charged with tax evasion or anything else, nor were Raising Malawi or Spirituality for Kids. It’s also not possible to determine the status of any investigation that might exist today: A spokesperson for the IRS referred VICE to the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York, who said, “I don’t think I would even be able to comment about whether there even was such a probe.” Raising Malawi, meanwhile, began formally separating from the Kabbalah Centre the same year, and today operates as an independent organization.

The most recent lawsuit, from the seven former chevre, says that after media reports began surfacing in 2011 about the IRS probe, “the Centre told chevre that this was a test of a chevre’s belief in the Centre and its purported mission, and provided chevre with ‘talking points’ to use should anyone ask them about the investigation.” It adds that chevre never learned anything about the outcome of the investigation, however, or “whether it continues to this day.”

At the same time, the lawsuit alleges, the Centre had become “concerned by negative press and the IRS investigation.” For years, the chevre were given “allowances,” they say—around $25 a month in 1998 and up to $300 a month 20 years later. In 2012, they began to be paid what the lawsuit calls a “nominal salary,” saying the Centre would instruct chevre to return it to the Centre in the form of a ‘donation,” adding, “Oftentimes chevre would do this.” (In other words, they allege the paychecks were a ruse designed to make it appear as though they were compensated fairly, but that they were encouraged not to keep the money.)

When the chevre left, the lawsuit adds, “they were typically penniless,” without any possessions or anything the Centre had provided to them during their employment. They also had no financial footprint, the suit adds: “They often had no bank accounts, no credit history, no rental history—not even a utility bill to prove their residence in the cities in which they had lived.”

After their departure, several ex-students or ex-chevre began referring to the organization as “a cult.”

“For the last 2 years, I’ve been in the process of healing from the dreadful outcomes of being in a cult for 20 years,” one of the new lawsuit’s plaintiffs, Ofer Shaal, wrote on Facebook at the end of 2017. “My cult of choice? Oh, it was kabala center [sic].” (The misspelling seemed to be deliberate; Shaal added wryly, “The Rav used to say, it doesn’t matter what they write about us, as long as they spell our name right.”) On social media, ex-member Lew De Payne—the one confused about the spiritual math involved in Kabbalah and Pinchas waters—has denounced it as “yet another cult using the pretense of spirituality to induce its members to donate to their nonsense.” And the ex-student with the eating disorder who left in 2004 told us the term feels “accurate” to her.

Rick Ross, a cult specialist who’s tangled publicly with the Kabbalah Centre for years, tells VICE that, in his view, the group is “absolutely a cult.” In an online video, he’s pointed to the famous 1981 paper by Robert J. Lifton that defines the elements of a so-called “destructive cult.” They are, as Ross explained: “The existence of an absolute authoritarian leader that is the defining element and driving force of the group,” and that the group “uses a process of thought reform to gain undue influence over people through psychological and emotional manipulation.” Another key element is that people are “are exploited by the group,” he said.

The Kabbalah Centre’s description of itself is a lot more staid, particularly in court documents. In countering the new lawsuit, the Kabbalah Centre has argued that the chevre knowingly and willingly consented to a vow of poverty, as well as waived their right to sue. It also claims that because the Centre is a religious nonprofit, the court doesn’t have standing to intervene in their affairs, citing the “ministerial exception,” which has been recognized by the Supreme Court and bars religious organizations from being sued by employees who carried out religious functions.

Ultimately, the Centre’s attorneys argue, “Plaintiffs ask that the Court do exactly what the Constitution prohibits: to analyze the theology underpinning the Chevre’s abnegation of material possessions and wages and the religious doctrines of Kabbalah.” The plaintiffs, they argue, are unacceptably demanding that the federal court system “‘take sides in a religious matter’ by determining whether it is proper for the Centre to accept this type of sacrifice from the Centre’s Religious Order of Chevre.” (Attorneys for the Kabbalah Centre did not respond to two requests for comment from VICE.)

The conflict, though, between what’s being claimed in court documents and what’s been claimed publicly seems somewhat stark. On its webpage, for instance, the Centre takes pains to describe itself as a spiritual organization, not a religious one, as it has for many years: “We teach spirituality for the modern world,” it reads. “As the wisdom of Kabbalah predates religion, this is a study that can enhance any individual’s spiritual life and bring a new depth of understanding to all religions.” The chevre lawsuit points out that a 2010 version of the site was even more blunt, writing, “People often ask, ‘Is Kabbalah religion?’ The answer is no! Not at all!’” (That said, there’s no question that the Kabbalah Centre takes its basis from Judaism, and they celebrate many Jewish holidays.)

In their motion to dismiss, the attorneys for the Centre and the Bergs added, “Having abjured standard professions or jobs, and having taken a literal vow of poverty in the course of becoming Chevre, the Plaintiffs now—somewhat incredibly—bring claims against the Centre pursuant to federal and state wage-and-hour laws (as well as related common law claims), seeking overtime and minimum wages for the services they performed as Chevre.” Noting that the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint, the lawyers calls those emendations “heavy-handed revisions,” but say the chevre’s claims “cannot withstand scrutiny and should be dismissed in full for several independent reasons,” including the ministerial exception. They also produced signed agreements from several of the chevre, showing they were offered a monetary severance (the amount is redacted) and in return agreed to waive their right to sue.

Ordinary Kabbalah Centre students tended to assume that the chevre were provided for, several ex-students told us. Robin was involved in the Kabbalah Centre from 2002 to 2010, and said she understood the chevre’s position, and how the students provided for them, to be in line with Jewish notions of charity. (Robin provided us with her full name, but asked we only use her first name. She works in the Jewish world and was concerned her past association with the Kabbalah Centre would harm her professionally.)

“It was positioned that it was on us as a community to provide for the chevre, that these beautiful souls gave up their lives, their worldly possessions, sometimes even their family—basically everything—for the Centre,” she said. “That’s very common in Judaism, that the community takes care of the rabbi or those teaching Torah. So it didn’t seem odd. What did seem odd is that general donations made to the Centre— we were encouraged to ‘tithe’ once a month—never seemed to make their way to the chevre.”

Robin said the chevre also gave her a high-pressure sales pitch, particularly after her father died. She knew it was traditional in Judaism to give tzedakah (charity) in someone’s name after they’d passed on. But one chevre, “a person I considered a friend,” she said, told her that the money was also used to help the dead loved ones “on their ascent into higher worlds.”

“She told me that it was on my shoulders to make this happen for my father’s soul and that I should give as much as I could,” Robin said. She was told that stickers would be printed in prayer books or Zohars with his name, to honor him.

It seemed reasonable to her, she said. “I’ve seen similar in other synagogues, plus I didn’t want his soul to not ascend.” She wrote a check for $3,000, though she couldn’t really afford it: she was unemployed at the time, and had to take the money from savings and post-date the check.

The experience left her unsettled, she said, and she almost felt as though the chevre’s demeanor physically changed as they talked about the donation.

“It was so bizarre. As soon as we started talking about money, her pupils dilated, like you see when a cartoon character is hypnotized,” she remembers. “The voice in my head was like, ‘What’s wrong with her eyes?’ It just didn’t feel the same as the other times we had talked. But I decided it must be me—I must be reading this wrong, this is a person who cares about me.”

The stickers never appeared in a prayer book, a Zohar or anywhere else, she said. “For years I asked different teachers and chevre about them. Always the same response: ‘How awful. Let me look into it.’”

Nothing ever happened, Robin said, and over time, her views on the Kabbalah Centre began to change.

“It’s like a crack and the crack gets wider and wider,” she said. Among other things, she remembers being told repeatedly that some students’ donations were going to be used for the construction of new Kabbalah Centres in a variety of cities. “I remember thinking, they keep talking about building new centers, what are they talking about? I’ve been here five years. There are no new centers.”

The Kabbalah Centre’s troubling past, present, and uncertain future is again, humming somewhat urgently beneath the surface of Yehuda Berg’s humble attempts at drawing the spotlight back onto him.

For the most part, for much of our conversation, Berg seemed thoughtful and repentant about the damages his behavior caused to his community and his family. When I pointed out that he seemed to be blaming his behavior solely on addiction, he responded, “Everything in my life I’ve ever done is 100 percent on me.” He added that his wife and family were somewhat tentative about his plans to return to the public eye.

“There’s definitely some fear and not just for her, also with me,” he said of his wife. “You know, being any kind of public figure, there’s a power in that and can be its own drug. If I smell a whiff of everything that I used to be coming back, I’m going to trash this and do something else. I’m not going through a whole loop again that goes into a whole down crash.”

That said, he acknowledged that he probably would’ve taken the chance to be a public figure again soon after his downfall, had it been offered. “Did I think I could do this in year one?” he said. “I probably thought that. And you hear all these people who end up in the hospital OD-ing because they thought that.”

But his tone changed immediately and noticeably when I referred to what he was accused of doing to Jena Scaccetti as “sexual misconduct.” He became businesslike, almost clinical.

“There was no claim of sexual abuse,” he said. “In the actual trial, maybe she said that to, you know—there were two counts. I was found not liable for sexual battery and was liable for infliction of emotional stress.” (It was emotional distress, but Berg is correct that a jury found him not liable for battery. At the same time, there is very little doubt that there was a sexual element to what Scaccetti accused him of doing, and for which he was ordered to pay thousands of dollars in damages.)

Berg, despite this, said that he now feels grateful to Scaccetti for suing him.

“Right after the incident and getting served papers and all this, I wanted to do what I could to apologize,” he said, but his lawyer advised him against it. “I think about her. I thank her. Had she not served me the papers-—that started this whole path of recovery.” In that way, he said, “I’m definitely grateful to her.”

“I haven’t heard anything from her since trial,” Berg added. “I know that she started a business and was doing better. We are both are in better places than we were between the incident and trial. I hope she would see me for who I am today and not who I was.”

I told Berg that I’d heard other, second-hand allegations of sexual boundary-crossing from him, and asked if he’d like to respond.

“No response,” he said.

A silence extended on the line.

Finally, he repeated, “No response.”

The second time we spoke, a few weeks later, I asked more specifically about the ex-chevre who said she’d been deeply confused and troubled by the experience of her spiritual mentor sending her sexual chat messages and asking her to play strip poker.

“No response,” he said again.

“Why not?”

Berg sighed. “It’s very, very complicated,” he replied. “My problem is that I have a really bad recollection. I don’t want to tell you something didn’t happen and it did. If i have to swear on, if you ask me 20 questions, and I have to swear on them, I couldn’t swear either way. If you ask me on a certain day, was I in Africa—I’ve woken up and not known the country I was in or what day it was. A lot of the substance abuse—and again, I’m not blaming that, I’m just explaining it—caused blackouts. If you ask me specifics, that’s something I could go into deeper, but generalization, I don’t know that I even have the capacity to even answer questions.” (He did specifically recall the details of the Scaccetti incident, he said, due to “trial prep.”)

The first version of the complaint filed by the ex-chevre claims that some of the chevre ultimately only left the Kabbalah Centre in the aftermath of Yehuda Berg being accused of assaulting Scaccetti. “Despite promises that he would no longer be affiliated with the Centre,” the suit says, “he continued to seek donations for it and continued to advise [Karen] Berg on Centre operations and decisions.”

Karen Berg was reportedly seriously ill this summer, and last wrote on Instagram in August that she was healing from surgery, and thanking people for their prayers. Blog posts bearing her byline have still appeared on the Kabbalah Centre’s website, but the chatter among some ex-chevre is that she may be retiring or taking on a less prominent role soon, opening a power vacuum.

“Last I heard, there have been splits,” said Rick Ross, “and certain prominent teachers that have left and taken students with them.” (In their article on Adam Neumann, Business Insider reported on an “exodus of frustrated teachers and students” in 2017, the same year Neumann left. One ex-Kabbalah Centre social media group has a posting listing six teachers who quit in one day. Several of those ex-teachers appear to now run their own Kabbalah-based life coaching services.)

VICE reached out to Jena Scaccetti, who today goes by Jena Covello. In recent years, she’s become the CEO of her own beauty and wellness company.

“It is troublesome to hear that up until this day from members at the Centre that he refuses to admit he did anything wrong,” she told VICE via email. “Those who are in a position of power and working with vulnerable human beings/addicts have an obligation to maintain a professional boundary.”

Covello also added that taking Berg to court “is one of the best things I ever did, because I learned to stand up for myself.” She wrote:

“There’s an old saying that secrets make you sick. I encourage anyone who has been abused or taken advantage of by an authority figure to heal, confront and come forward.”

In the end, she added, “If you’re seeking help for addiction recovery, my advice is to carefully vet the person’s reputation that you’re going to be working with and to be mindful of how they make you feel. Your intuition is always there to guide you.”

Berg responds that he hopes Scaccetti will one day forgive him.

“I would love,” he said, “to get to the place where I’ve really forgiven every single person who wronged me and every single person I’ve wronged would forgive me.”

Covello finally received her settlement money from the Berg trial earlier this year; after attorney’s fees, it amounted to a total of $30,000, which she says she didn’t keep. The possible source of the money, she explained, disturbed her.

“I wasn’t sure if this money is really the source of donations from members or past members who left,” she wrote. “The money doesn’t feel clean, so it has been donated.”

Correction, November 27: An earlier version of this story incorrectly summarized why an anonymous former chevre asked for her name not to be used; she did not want to be publicly associated with the Bergs, but did not fear retribution for telling her story.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

More

From VICE

-

Shutterstock for Consensus -

Photo by Costfoto/NurPhoto/Shutterstock. -

Marilyn, an attorney and former professional dominatrix, poses for a photo with her sub who is fully encased in latex on the Vancouver Fetish Cruise. Photo by Paige Taylor White. -