GARAGE is a print and digital universe spanning the worlds of art, fashion, design, and culture. Our launch on VICE.com is coming soon, but until then, we’re publishing original stories, essays, videos, and more to give you a taste of what’s to come. Read our editor’s letter to learn more.

When Kara Walker’s enormous frosted sculpture A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby appeared in Brooklyn’s old Domino refinery three years ago, it drew 130,000 visitors, gracing endless selfies before being demolished. Now it’s back, at least in part. Figa, a solitary paw salvaged from the original Styrofoam-and-sugar sphinx, went on display recently on the Greek island of Hydra, courtesy of supercollector Dakis Joannou. Carl Swanson went to get reacquainted.

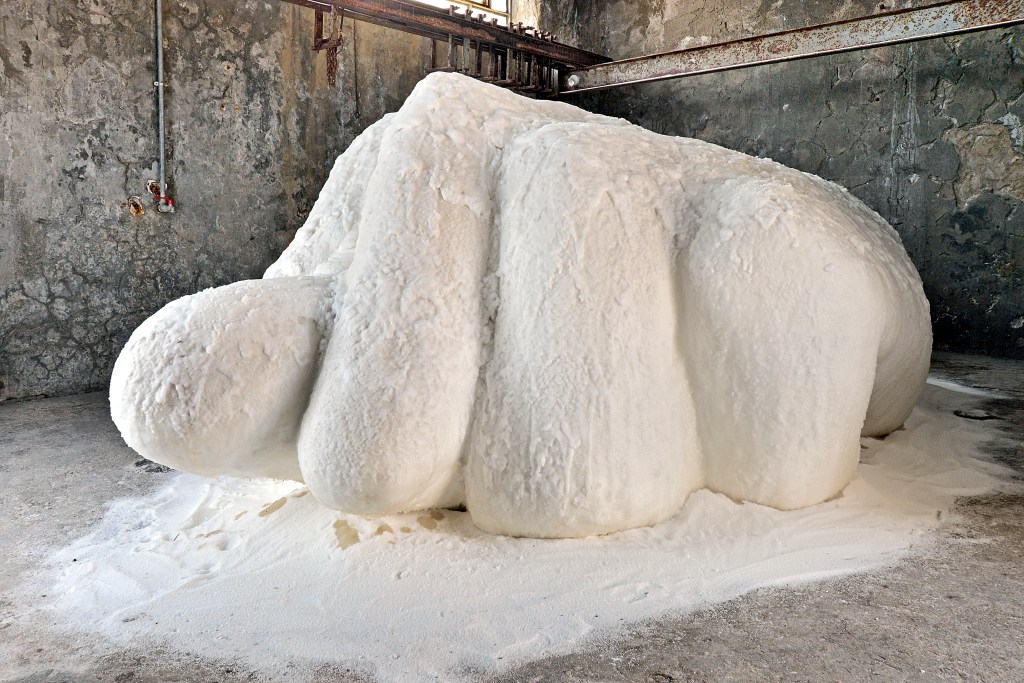

From now through September, in a former slaughterhouse on the Greek Island of Hydra, the severed left front paw of Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby rests on a bed of that white powder, looking rather like a trophy dessert. The bunker-like room is so small they had to remove the door frame to slide the limb in, and even then it was a tight squeeze. The paw is all that remains of the 75-foot-long, 35-foot-high mammy-headed sugar sphinx that presided over the decommissioned Domino refinery in Brooklyn for a few heavily Instagrammed months in the summer of 2014.

Videos by VICE

Over 130,000 people saw the work there, ten-foot-tall vagina and all, many standing in line for hours to get a look at this grimly delightful pop-up monument to the brutal nineteenth-century trade and its cultural aftertaste. Sublime and slyly discomfiting, it was great public art. And then it was gone. The developer who’d bought the Domino plant wanted to remodel the space into the centerpiece of a massive set of waterfront apartment towers. Walker’s London gallery Victoria Miro looked into having Tate Modern reprise the work, but—in spite of the fact that Tate Britain was founded on the collection of sugar refiner Henry Tate—nothing came of the idea.

But even as A Subtlety became a selfie magnet, artist-anthropologist Walker was watching us too, secretly recording viewers’ reactions. The artist later assembled her footage into a film, An Audience, screening it at her gallery, Sikkema Jenkins, alongside the souvenir forearm after the frosted Styrofoam structure had been demolished. And here’s something I hadn’t noticed while looking at the sculpture in Brooklyn: the figure’s thumb is tucked between her fingers to make a figa, a mildly obscene gesture in some cultures which might signal that Sugar Baby is DTF. Or perhaps the message is one of female empowerment. In any case, the installation on Hydra was named for the sign.

At the invitation of Greek-Cypriot supercollector Dakis Joannou, Walker, the severed limb, and her boyfriend the photographer Ari Marcopoulos had undertaken a working vacation to the prosperous tourist isle (also a stomping ground of Leonard Cohen and Brice Marden). Marcopoulos has family on the island too, and during my visit Walker was often besieged by her cheery Greek in-laws. If Walker seems to have an intellectualized, conflicted relationship to her fame—again, she’d mostly rather watch us—Marcopoulos is youthfully gregarious. She in floppy hat and sundresses, he in skatewear, trucker cap, and bushy gray beard, they complimented each other perfectly.

In 2009, Joannou decided to turn Hydra’s old slaughterhouse into a project space. As a collector, Joannou is indulgent; he wants to see what will happen. Every June, he makes a weekend of it, and the opening festivities have become one of the more idiosyncratic dates on the art-world circuit. And absent overt corporate sponsorship and branding opportunities, it’s really just the Dakis Show, a product of his peculiar ambition. The guests vary a bit each year, depending on the exhibitor; Joannou has had long relationships, and made early calls on, many consequential artists, notably Maurizio Cattelan and Urs Fischer. Jeffrey Deitch and Massimiliano Gioni are among his longtime consiglieri.

The Hydra opening comes at the end of Joannou’s annual Deste Foundation weekend, one aim of which is to promote Greek contemporary art internationally. So there are events in Athens and a party at his house there. Maybe surprisingly, the house is not architecturally remarkable, more a big, comfortable Mediterranean box set into a hill. But inside it’s an enchanted toy chest of contemporary art amusements. His Superstudio furniture makes even sitting around fun. It’s the sort of party at which it takes you a minute to realize the gangly Brit who’s telling you a story about the time Ivanka Trump hit on his friend backstage at a rock concert is artist David Shrigley—he’s doing the Slaughterhouse next year—and where Maurizio Cattelan manages to lean on wet black paint before, catching my eye across the room, pretending he’s going to wipe it off on Joannou’s back. When Joannou turns around, he laughingly commissions some handprints on the wall. The next day, everyone goes to Hydra, the luckiest aboard the Guilty, Joannou’s yacht, which Jeff Koons painted in Pop-art camouflage.

Walker was already on the island, getting ready; she and Marcopoulos had found an Athens-based hip-hop collective, the ATH Kids, to play the opening party. The artist wouldn’t be drawn on what Figa might mean when divorced from the context of the Domino plant, but she did offer a deadpan account of her thinking in an interview earlier this year: “What’s going to happen is, this summer, the important art people of the world are going to go to the Venice Biennale, and then they’re going to go to Art Basel, and then some of them are going to get on a boat and come to Hydra and see something they’ve already partially seen.”

For the record though, not everyone had in fact made it to Brooklyn: the art-world worthies who show up at Joannou’s Hydra openings often fly across the world before they’ll take the L train (“I have a problem with Brooklyn,” confided one fellow traveller in Hydra who’d missed the work there, but was busy trying to figure out how to make it to overlapping openings in Istanbul, Los Angeles, and Chicago in September.) Joannou was among those who had made the trip. He even stood in line, he told me with a mischievous twinkle as we waited for the performance to begin.

For the party, they’d set up turntables and a screen on the roof of the slaughterhouse, which sits below the level of the road on a scrubby waterside bluff. The road was the viewing platform, and the hundreds of guests—anyone who wandered up from the harbor was welcome—feasted on Greek food and ice cream. Walker and Marcopoulos had decided that the ATH Kids would perform in front of a projection of parts of An Audience, including sequences of the sugar baby being dismantled, intercut with news footage of migrants trying to sail to Greece, bodies being plucked from the sea. Not that the ATH Kids seemed to have anything specific to say about the migrant crisis (sample lyric: “We don’t need no caution/that’s just cuz we awesome”)

But globalization’s effects on culture—hip-hop is youthful self-assertion’s lingua franca, no matter where you’re “from”—seemed to be one of the points. The night was lovely and the vibe fun if you didn’t think too much about how undigested this hodgepodge of concerns appeared to be, images of bodies floating in the sea paired somehow with whatever the ATH Kids experience of being non-white in Greece might be. Several Europeans I spoke to had a more negative reaction, though, seeing this as the offensively trivializing vision of an American who just didn’t “get it.” Not that Walker has ever minded offending. She doesn’t sugarcoat.

It used to be that Athens was an archive, source material for the Western Civilization myth industry. Documenta, that most serious of contemporary art surveys, named its current iteration “Learning from Athens” because so many of the fault lines that run through our global system happen to converge here. It seemed to be arguing that Athens could teach us about the future too, breaking away from its Kassel base to present a satellite set of Documenta exhibitions and performances in the capital. Some local intellectuals compared the entire endeavor to colonialism—former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis rubbished it as “crisis tourism”—but it’s difficult to imagine an alternative. To quote a text piece by Karl Holmqvist on display at The Breeder, one of Athens’ most interesting galleries, “It’s painful for me to face the fact that art cannot contribute to the solutions of urgent social problems.”

Amid the hubbub of the Slaughterhouse opening, it was easy to miss a white plaster mask by Walker that sat in a small alcove, attended by a votive candle. The edges were formed like pie crust and it was about the size and shape of Duchamp’s Fountain, but turned upside down and propped up on more sugar. An image of what I took to be the artist’s face—Walker’s studio later informed me that it was in fact made from a copy of a bust by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux titled The Negress—had been pressed into the soft material and looked up at us, assessing.

Carl Swanson is editor at large at New York magazine.