Say this for the upcoming Will Smith film Concussion: it may be a major feature film, but it’s real enough to eschew a happy Hollywood ending.

Based on actual events, the movie tells the story of Bennet Omalu (Smith), the Pittsburgh-based neuropathologist who in 2002 discovered the neurodegenerative disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in the brain of deceased Pittsburgh Steelers and Hall of Fame center Mike Webster. His groundbreaking work ultimately helped lead to the PBS documentary and book League of Denial, a federal class action lawsuit against the National Football League, and greater public understanding about how getting hit in the head repeatedly, even while wearing a hard plastic helmet, can cause brain damage.

Videos by VICE

In the film, as in real life, Omalu publishes his discovery in a scientific journal. He expects the NFL to take heed and corrective action. After all, football-induced brain trauma is making men mad. Destroying families. Ruining lives. Surely, Omalu reasons, the league will want to understand the problem, the better to solve it. Surely, no mere game is worth such a terrible price.

Perhaps, Omalu thinks, the NFL will even thank him.

Read More: If Sydney Seau Does’t Speak Out Against the NFL, Someone Else Will

Spoiler alert: Omalu doesn’t end up on the league’s Christmas card list. Motivated by corporate greed and existential fear, the NFL pushes back in the manner of Big Tobacco—and really, almost every other industry that produces health harms, from coal to asbestos makers to soda manufacturers—by attempting to bury Omalu, discredit his work, deny CTE’s existence, and duck both legal liability and moral responsibility for the damage done to people like Webster.

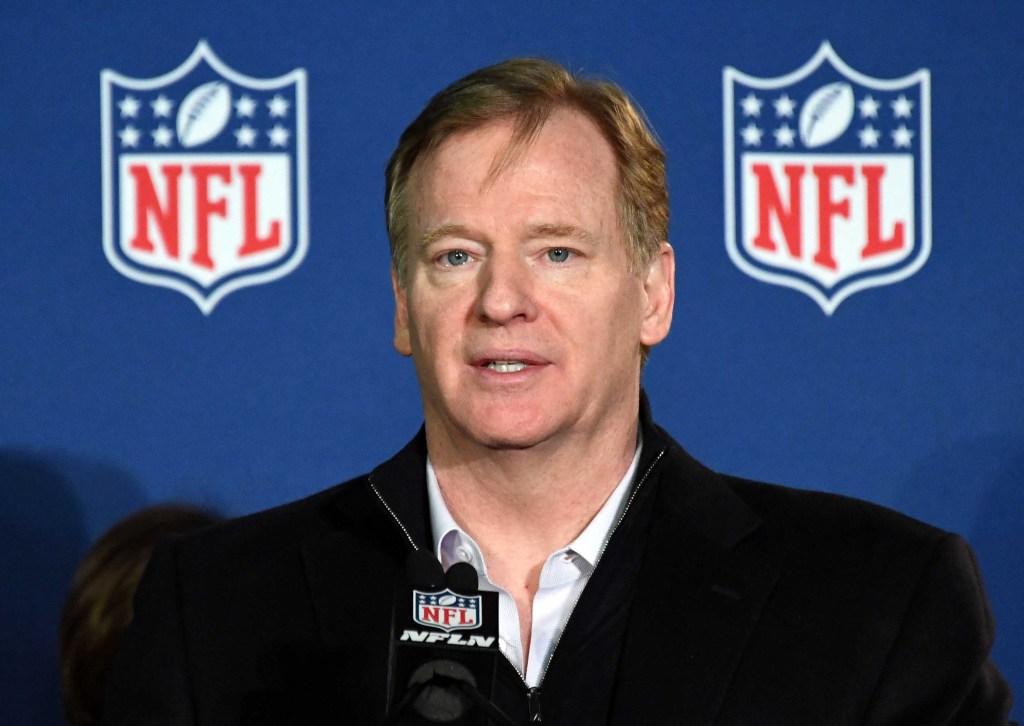

NFL medical advisor Elliot Pellman (played by Paul Reiser), a Guadalajara-educated rheumatologist who somehow chairs the league’s longstanding brain trauma research committee, demands that Omalu retract his Webster paper. As Omalu finds CTE in the brains of other retired players who have lost their minds, including Terry Long, Justin Strzelczyk, and Andre Waters, NFL-affiliated doctor Joe Maroon (Arliss Howard) publicly asserts that Omalu is full of shit. In a meeting between the two men, he all but orders the Nigerian-born Omalu to stand down because football. And America. The league holds a high-profile brain damage summit, prevents Omalu from speaking there, and afterward belittles his discovery before a roomful of reporters. All the while, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell—played in deadpan, subtly hilarious, self-satisfied android fashion by actor Luke Wilson—appears behind podiums and microphones, mouthing empty platitudes about player safety and getting to the bottom of things while never displaying an iota of actual curiosity or empathy.

Now, if Concussion were a typical Hollywood film—particularly a cornball sports flick, like, say, Rocky IV—it likely would end on a note of unambiguous triumph. Good guys rewarded, bad guys punished, all problems resolved. But the movie, to the credit of writer and director Peter Landesman, is far more nuanced. I’ve seen Concussion. Without giving away its ending, I can say that the story hews closely to the actual events that inspired it, and that the lawyers who vetted and fact-checked the project appear to have done a good job. If the film lacks a sunshine-and-lollipops denouement, it’s only because real life lacks one, too.

To wit: there is no bronze statue of Omalu outside the NFL’s headquarters in Manhattan. To the contrary, he has been stiff-armed by the league. When Omalu contacted the family of former league star Junior Seau in 2012 to inquire about examining his brain, a NFL-affiliated doctor reportedly smeared Omalu, ensuring tissue samples went elsewhere. Seau subsequently was diagnosed with CTE. Meanwhile, information about the disease and football’s other brain damage risks have trickled out through the media to an increasingly aware public—though little credit should go to the NFL, which mostly has kept boasting about a less dangerous sport while largely refusing to acknowledge or be held accountable for the occupational hazards Omalu made plain.

Cinematic Roger Goodell (Luke Wilson), flanked by Elliot Pellman (Paul Reiser), right, and Joe Maroon (Arliss Howard), left. –YouTube

The good news? Since the timeframe covered by the film, the NFL has enacted stricter, standardized return-to-play rules for concussed players, donated money for medical research, and publicly admitted—exactly once, but still—that concussions can cause long-term cognitive harm. The bad news? Just about everything else.

Take Pellman. Despite his lack of medical qualifications, and his potential conflict of interest as former NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue’s personal doctor, he chaired the league’s Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee from 1994 to 2007. Pellman’s committee published research that downplayed and dismissed football’s brain trauma risks, claiming things like concussions in professional football “are not serious injuries” and that “many [concussed] players can be safely allowed to return to play on the day of injury.”

Independent scientists have discredited those claims. A Congressman later labeled them “infected.” They’re at the heart of League of Denial, and of the more than 4,500 lawsuits filed by former players against the league alleging negligence and fraud. They led to players at all levels of football, from Pee-Wee to the pros, unknowingly absorbing additional brain damage. No matter. Pellman’s committee ultimately was disbanded, but he was never fired. As of 2013, he still was working as a NFL medical advisor, overseeing at least a handful of player concussion evaluations. Moreover, none of his papers have been retracted.

Or consider Maroon. Still the Pittsburgh Steelers’ neurosurgeon and also a consultant to the league’s revamped and renamed Head, Neck and Spine Committee, he said on NFL Network in March that football’s long-term neurological dangers are “overrated,” and that riding bicycles and scooters are more dangerous to children than playing football. This shouldn’t be surprising. In 2013, Maroon was a co-author on a NFL-funded study claiming that youth football players should spend more time—not less—tackling each other in practice. For safety. Earlier this year, Maroon published another paper suggesting that CTE may not be tied to contact sports, but failed to mention his longstanding league ties.

Again: nothing happened. Maroon was mocked on Twitter—!que horrible!—but the NFL didn’t dump him.

“Hi everyone! Call now to discuss the NFL and job security!” –YouTube

In the Concussion trailer, former NFL team doctor Julian Bailes (Alec Baldwin) tells Omalu, “You turned on the lights and gave [the league’s] biggest boogeyman a name.” In the years since the events of the film, supporting evidence for CTE and its link to football has only grown. As of last year, Boston University researchers had found CTE in the brains of 76 of the 79 deceased former NFL players they examined, an alarming percentage despite a necessarily skewed sample size. (CTE currently can only be diagnosed after death, and NFL retirees who suspect they are suffering from the disease or are experiencing its symptoms are more likely to donate their brains to science.) Earlier this year, an international group of neuropathologists working with the National Institutes of Health agreed upon the first pathogonomic indicator for CTE—that is, the signature brain damage that distinguishes the disease from other, similar ailments. A recent Harvard University study identified what appears to be the first observable physical link between repetitive head trauma and the misshapen, microscopic brain proteins that characterize CTE. A proposed settlement of a class action concussion lawsuit against the National Collegiate Athletic Association estimates that for athletes whose college sports careers began between 1956 and 2008, anywhere from 50 to 300 of them per year will be diagnosed with the disease.

Oh, and all of this comes alongside other evidence that football is bad for one’s brain in all sorts of ways that don’t involve CTE.

Given all that, you might assume that the NFL would, you know, say something. Guess again. In supporting documents for the proposed settlement of the class action concussion lawsuit, the league’s own actuaries estimate that nearly a third of retired players will develop long-term cognitive problems. Asked about those numbers by the New York Times, a NFL spokesman declined to comment and referred reporter Ken Belson to a lawyer representing the league. The lawyer promptly claimed the numbers were inflated. Two years ago, Goodell repeatedly refused to acknowledge a link between football and brain damage while appearing on Face the Nation; more recently, Indianapolis Colts co-owner Carlie Irsay-Gordon told Glamour that “women’s soccer actually has more concussions than we do, I think because of the headers that they do. Rugby has its hazards. Running [too].”

Also at increased risk for concussions, brain damage, and neurodegenerative diseases, at least according to a NFL team co-owner. –Photo by Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports

As for the CTE boogeyman? Concussion notes that retired NFL players began suing the league en masse in 2011 for concealing the dangers of concussions. But the film doesn’t mention that the proposed multimillion-dollar settlement of those suits arguably is designed to limit and deny compensation to former players suffering from CTE, failing to compensate the severe, life-ruining mood and behavioral symptoms associated with the disease and only providing cash payouts to the families of players who have died and subsequently been diagnosed with the disease between 2006 and April of this year. All this comes regardless of future medical advances in CTE diagnosis and treatment, and despite the fact that, of the various neurodegenerative conditions covered by the deal (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, severe dementia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), only CTE requires getting hit in the head.

Then again, this is the same NFL that currently wants to suspend New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady based on the overwhelming scientific evidence contained here.

During a face-to-face, don’t-bother-coming-to-Jesus meeting between Omalu and Maroon in the Concussion trailer, Smith’s character points his finger at the NFL doctor. He has heard too much obfuscation and denial, and seen the terrible truth through his microscope and on the coroner’s slab. Omalu is a medical doctor, not a football salesman. He is, as he says during the film, offended by what is happening. The league has crossed a moral line. “Tell the truth,” he says. Tell the truth.

Fat chance. In real life, Bennet Omalu spoke up. Doing so cost him. Meanwhile, Maroon is doing just fine; Pellman, too. The NFL is making more money than ever. When former San Francisco 49ers linebacker Chris Borland recently retired after his rookie year, he did so after conducting his own research into the brain damage risks of continuing to play, and not because the league had anything informative to say. There’s a happy ending to the real-world events that inspired Concussion, and it involves Goodell’s personal wealth manager. Perhaps the filmmakers get this. Like their protagonist, maybe they know the truth. Maybe they know there’s room for a sequel.