Jonathan was 20 when he left orthodox Jewish school, or yeshiva, and got his first computer: a ThinkPad laptop to get him through his college program in engineering. Having grown up in Jerusalem in the 1980s and 90s, he had gone the entirety of his life without a computer, or even a television at home—as was, and remains customary to varying degrees among Haredim, or ultra-Orthodox Jews. Still, that didn’t stop the future programmer from falling in love with computers.

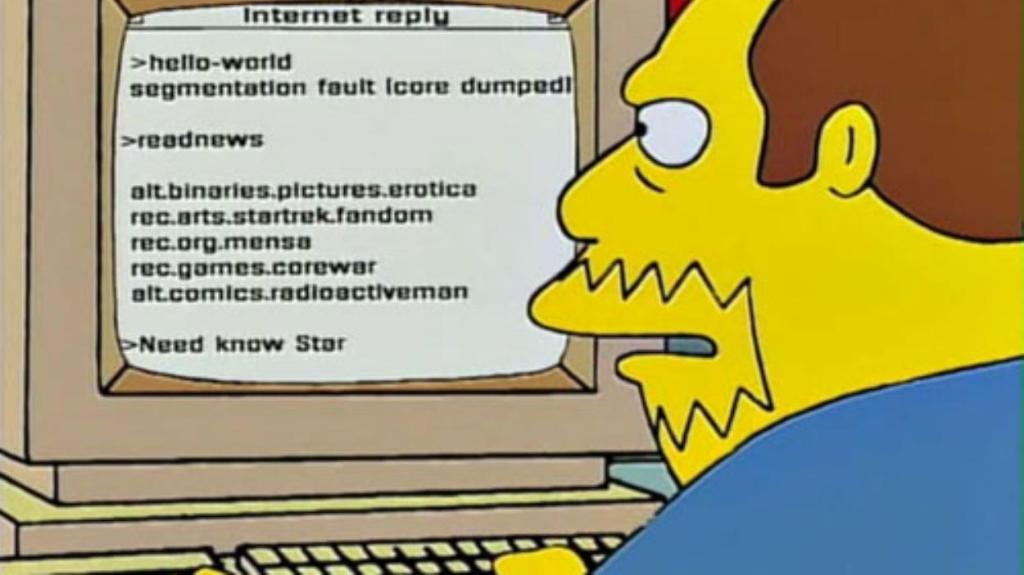

While packs of yeshiva boys would sneak into town, crowding internet cafes to watch soccer or porn, or merely to cruise the web—the secular world only a click away—Jonathan hacked his school’s internet filters blocking certain websites in the name of ruchnius, or spirituality. Though he had ventured outside the insular Haredi community where he grew up, the Jerusalem College of Technology still adhered to strict codes of religiosity, which included filtering the internet.

Videos by VICE

Today, a number of filters, including Jnet, Rimon, Netfree, Netspark, and Yeshivanet, serve orthodox homes, schools, and businesses around the world, including Israel, Europe, the United States, and South America. Filters aren’t all-or-nothing roadblocks, but obstruct certain words, images, or pages within a site that’s allowed. And they’re intended not just for children or black hat Haredim, but for the modern Orthodox, religious people of other faiths, and even secular parents aiming to protect their kids.

“Porn’s not the biggest problem. You can also see other opinions.”

In the form of internet service providers (ISPs), or solutions between the ISP and the individual computer, the filters pick up on keywords, indicating what’s allowed or forbidden. To circumvent those keywords, Jonathan would type in Russian, since the filters operated in English, Hebrew, or Yiddish. Or he would type a website’s numerical IP address to avoid using words altogether.

Image: Advertisement for Guard Your Eyes

“You skip the stage of translating words to numbers, which tell the computer what to do,” Jonathan said. (For example, typing 172.217.25.36 will get you the same place as typing www.google.com.) When those methods failed, he would use a proxy, concealing both the user and location, to bypass the filter.

“Porn’s not the biggest problem,” Jonathan said. “You can also see other opinions.”

The unfiltered internet can be a threat to the integrity of yeshiva curricula or to family’s religious values. Social media, chat rooms, WhatsApp groups, or sites like Failed Messiah become a window outside the insular Haredi world. The anonymous soundboard of seculars and the ex-religious entice those questioning their faith.

While rabbis once tried to reject the internet altogether, telling people to stay offline is no longer a tenable position. Even among Haredim, the internet is integral to daily life, from running a business to buying airline tickets.

“Orthodox Jewish homes have valued for as long as anyone can remember the idea of filtering,” said Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein, editor of the Orthodox blog Cross-Currents and adjunct chair in Jewish law at Loyola Law School. “Not everything out there is of equal value and you’re trying to keep your home and head full of ideas and images that are healthy and productive, rather than the opposite.” That’s the chief reason why orthodox homes usually don’t have televisions, and why they do have internet filters.

While the internet is widely used to study Torah (the Jewish Bible) and other religious texts and ideas—”We refer to ‘Rabbenu [our rabbi] Google’ as one of the chief teachers in the community,” Adlerstein said—it can also challenge orthodox Jewish values.

Pornography is the most obvious problem. It violates Jewish values both by objectifying human beings and disrupting “inner purity,” Adlerstein said. Internet porn is more convenient than a furtive visit to the candy store to buy magazines and fosters unhealthy expectations in marriages, he added. “Filtering is about both keeping temptation at arm’s length, and maintaining the quality of inner peace where your mind is, and where your soul is,” Adlerstein said.

Exposure to secular or heretical ideas is another problem. “If a kid finds 20 websites that convince him that if you believe in God you might as well believe in the spaghetti monster, there are all kinds of intellectual issues—issues that people in the community try to stay away from, or welcome with the right age, maturation, and background,” Adlerstein said. “[Online] you have no way of controlling that. You have access to all kinds of cynicism that puts down the way your family lives and demonizes the way the community lives.”

Newer filters work in real-time, automatically scanning website pages for non-kosher material. Through a technology called “quilting”, the system is coded to decide whether a web page, paragraph, or image is kosher, said Zvika Ilan, vice president of business development and marketing officer for Netspark, a filter for computers and smartphones. Each customer can decide the level of filtering they want to use: For example, the most basic level would block only pornography, but more advanced levels would also block lingerie or swimsuit images.

“If we think that people don’t want to see harmful content, then in the highest level we will not even show them social networks,” Ilan said. YouTube is allowed under Netspark, but if indecent content comes up even within a few seconds, the video is stopped. The same happens when scrolling through Facebook: “We’re scrolling and deleting harmful content from the wall,” he said.

The filter “understands” what it sees, Ilan added. Whereas before old filters would pick up only on skin tones, that method failed with close-ups of faces, or if a porn video used a red light, for example, and the skin tones were different colors.

“Oops, we checked and sadly the content on this site is not good.” Image: Netfree.

“The systems today are updating every few seconds or minutes,” Ilan said. Netspark filters 200 million new images and 24 million new videos every day, and 500 million text characters every second, he said. And if the system can’t decide whether any particular content should be filtered, it gets moved to a human being.

“Tens of thousands of teenagers are making the move,” said Rabbi Moshe Weiss of Netspark, “Saying ‘I’d like to have a filter on my computer.’”

Other filters work off a “whitelist” of kosher websites and a “blacklist” of banned websites, explained Eliezer Reiton, Netfree support engineer. Netfree, which Reiton said has thousands of users, blocks a total of 42,000 websites, including porn, proxies, social media, most news sites, and most video sharing sites. Other filters, however, are more lenient, allowing for example the news or some social media. Google is the only search engine allowed, but the results are filtered. Wikipedia is open, with some pages and images blocked. Same with YouTube, blocking certain videos, and so on. All major email providers are open.

Every single image displayed through Netfree is screened by Gentile employees in Ukraine and India similar to the work done by laborers in the Philippines who “keep dick pics and beheadings out of your Facebook feed.” Technically, Jews shouldn’t subject other Jews to non-Kosher material—similar to reasons why a “Shabbos goy,” rather than a secular Jew, might help observant Jews with certain tasks so they don’t have to violate Shabbat.

Because of the “premium attached to keeping temptation maximally distant,” Adlerstein explained, pictures of women are blocked, in addition to naked newborns and naked or partially dressed men. The screening system is attractive to non-Jews, as well: Even Netfree’s Muslim employees in India have expressed interest in it, Reiton said.

These employees are given a very explicit set of instructions in the form of a web app, manual, and powerpoint to help them understand which images are kosher and which should be banned. All new screeners are also trained by more experienced screeners.

Netfree’s list of “Rules for blocking images” includes each image containing a number of specific traits, such as the following:

- “A human female above the age of 9, or a part of her body”

- “A human female above the age of 3 without full dressing. Meaning with a swimsuit, underwear, mini skirt without stockings, etc.”

- “A human male above the age of 6 without full dressing”

- “Prominence of intimate organs (can be in men’s underwear)”

- “Women’s lingerie, even if there are no women in the picture (bras)”

- “Naked human statues”

- “Sex-related” content

- “Obscene or disgusting [content]. For example—bodies, murder, evil, abuse, blood”

Images of women’s hands are okay, so long as there’s no nail polish. Screeners are also told to look out for rooms with pictures on the walls containing the above non-kosher imagery, as well as for pictures of pictures on computers, screens, tablets, and cameras.

Image: Guard Your Eyes.

To illustrate how Netfree works, Reiton experimented with various Google search terms to see the extent to which the results were accessible. Britney Spears was searchable, but her Wikipedia blocked. Hillaryclinton.com was blocked because she’s a woman. The same is true for the website for Knesset (Israeli parliament) member Tamar Zandberg, a less famous female politician, was open, but images of her blocked. Zandberg’s Wikipedia page was blocked. So was the Church of England.

Ironically, while the internet is the root of many issues in the orthodox community, it’s also a tool to alleviate those issues. “Caught in the shmutz [dirt]? Drowning in the internet?” beckons a site called Guard Your Eyes (GYE). The online GYE internet addiction services are here to help.

Internet addicts often feel like they’re living a “double life,” said Yaakov, founder of GYE, which has nearly 1,500 members. “On one hand, they’re living an orthodox life, studying in yeshiva, and on the other hand, they have the smartphone in their pocket and feel an irresistible urge.”

GYE offers help for varying levels of addiction: a call-in hotline, weekly “chizuk” (strength) emails, online chat forums for moral support, an anonymous 12-step program, and information on filters via the sister site Venishmartem (Hebrew for “you watched yourself”). GYE recommends keeping the computer in a common area, and also offers a partner program, in which internet addicts can have their browsing history automatically sent to a “web chaver [friend]” who keeps them accountable. “If you look at porn sites, your friend gets an alert and then it’s embarrassing to you,” Yaakov explained—and hopefully that helps addicts “break free.”

“The internet is a threat to spirituality, not just religion,” Yaakov said. “They’re two separate things. Religion depends on what you were raised to believe: that’s dogma. Spirituality is the simple belief that there’s a higher power, a loving God who is involved in our lives and cares about us.” You can be religious, but not spiritual, he said, and for addicts, the internet exacerbates that division.

Internet addiction goes beyond porn. It can also be an irresistible waste of time—a problem for seculars and religious, alike. “What a person does in his or her day is supposed to be tachless [purposeful],” said Rabbi Avi Shafran, spokesperson for Agudath Israel, a Haredi umbrella organization. “Wasting food, emotion, words, and time is seen as something that denies the value of life. God gave you a gift and you threw it out.” Wasting time is an issue especially for Haredim, who have a religious obligation to study Torah (not surf the web) during their free time.

But the bottom line is that the challenges the internet poses are just as present in the real world—whether it’s wasting time, watching porn, or bearing witness to inappropriate sightings on the street. (For instance, yeshiva boys may see a girl jogging in shorts and a sports bra through Haredi Williamsburg, but such an image would be blocked by filters.) Moreover, any tech savvy kid, like Jonathan was, can figure out how to hack the filters anyways.

“It’s an imperfect system. Assume [kids] are going to come across this one way or another, either through the computer or their friends. You can’t rely on the filter,” Shafran said. The key is “self-control and inoculation,” he added. “If you expose your kids to things that are not in consonance with our belief system, expose it to them outright. Teach by example and discuss with them why it’s wrong to watch pornography, for example. Let them read, let them question. They’ll know there are different approaches and they’ll learn how to reconcile them.”