When news broke recently that the US Justice Department is preparing criminal charges against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, the story reverberated across not only London, where Assange is holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy, but also in Iceland, where a bit player in the WikiLeaks story has been living for five years.

Six years ago, during a military hearing over the actions of Wikileaks source Chelsea Manning, a government witness testified that someone named “Jason Katz” helped WikiLeaks try to crack the password on a particular file. This file contained a video Manning allegedly leaked to the group (she was later acquitted of this charge). Katz has never spoken publicly about the matter and aside from his name and a few details presented in court, the story of his role in the incident has long remained a mystery.

Videos by VICE

Katz, now 36, tells Motherboard he made a single, failed attempt to crack the password. And WikiLeaks never ended up publishing the video. But Katz lost his job with a US government lab and, after an FBI raid at his work place, his apartment, and the home of his girlfriend’s parents, he says the feds subpoenaed him to appear before a grand jury investigating Assange and WikiLeaks.

Katz refused to testify without immunity and never heard from the feds again. He also was never charged with any crime. In 2012, he moved to Iceland, where he founded the Pirate Party with several former WikiLeaks associates, and says he has lived ever since on the “straight and narrow.”

Last week, Manning was released from prison after having her sentence commuted. But Katz is concerned that if the government now goes after Assange on conspiracy charges, it could go after him as well, however brief and inconsequential his role in the Manning leaks was.

“I don’t regret my actions, because they led me on a really interesting journey.”

Katz has kept a low profile since the raid and says he avoids speaking with friends in Iceland about his brush with the law.

“[W]hen I got raided, they rounded up my entire support network—all of my friends, all of my close family, and just wrecked all of that,” he tells Motherboard. “It made me very wary of involving anyone around me with what all of this was about.”

Several times during a voice call interview that he initiated with Motherboard, he questioned the wisdom of talking now.

“I’m being dumb,” he says. “You can put that on the record. I don’t want to say something that will create new charges or trouble for me at this point.”

Despite reservations, Katz spoke with Motherboard in an attempt to set the record straight about his role in the Manning case.

“I don’t regret my actions, because they led me on a really interesting journey,” he says. “I would do the same again. It got me to move here, and if I hadn’t moved here, the Pirates never would have happened.”

*

Katz was a 28-year-old systems administrator in late 2009, when he was in a WikiLeaks IRC room and someone mentioned a password-protected file they needed help opening. This was months before the first Manning leaks were published, and the public was still largely ignorant about WikiLeaks. The organization had been operating for three years at the time and had published a few news-making leaks from other sources, but these had garnered little attention inside the US.

Katz says he was drawn to the organization because he supported founder Julian Assange’s ideas about government secrecy and transparency, and he found the idea of helping WikiLeaks exciting.

“It appealed to the hacker ethos,” he recalls. “The David-Goliath archetype.”

It’s unclear exactly who requested help in the IRC room that day. Everyone in the group chat used pseudonyms and refrained from providing details that identified themselves, and Katz says he doesn’t know if he ever communicated directly with Assange. Motherboard contacted WikiLeaks for comment, but the organization did not respond in time for this article’s publication.

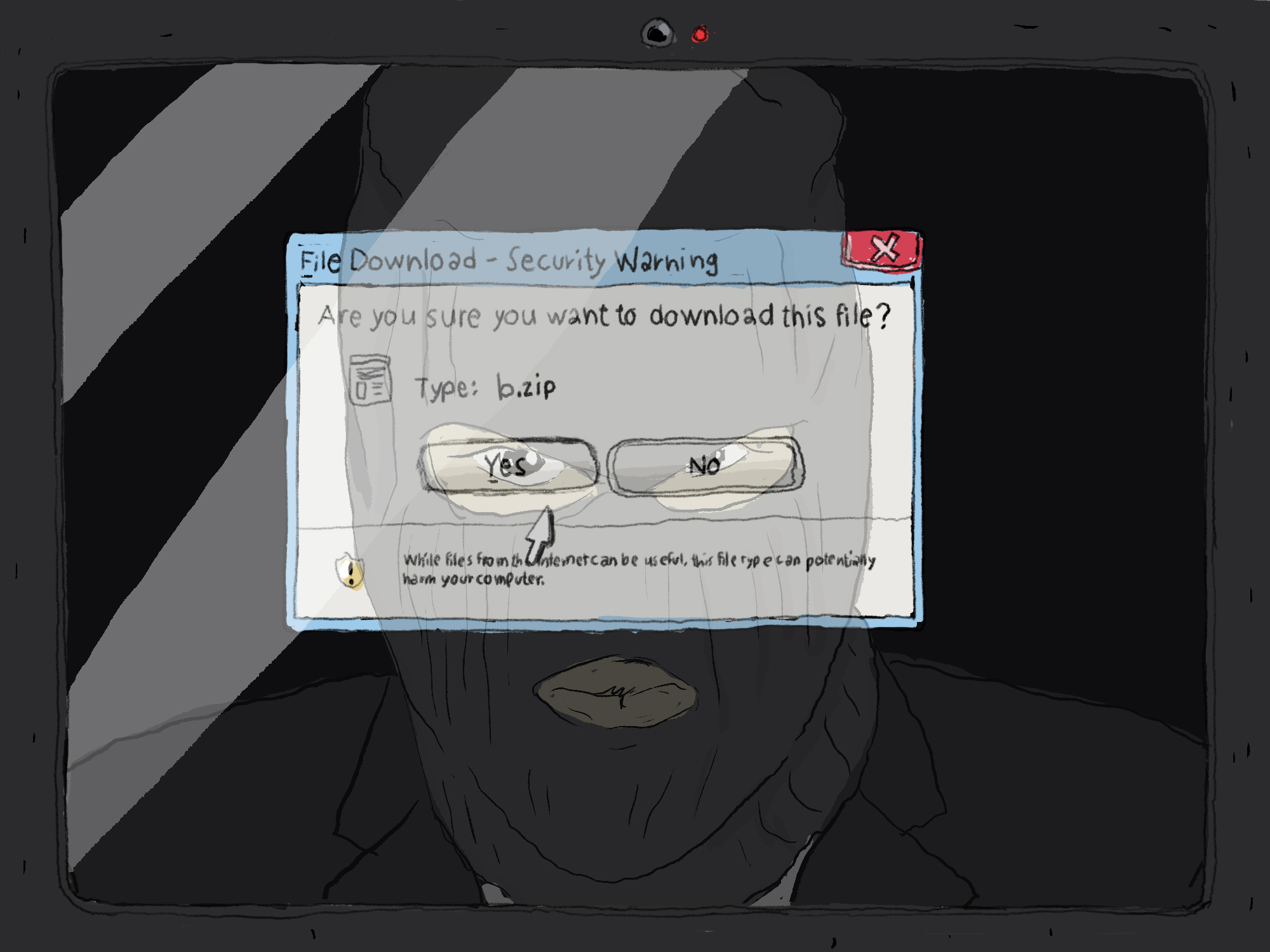

Katz decided to download the file, which turned out to be a .zip file called “b.zip”. He also downloaded a password-cracking tool to try to open it. But the password cracker didn’t work.

“That’s pretty much as far as I got,” Katz tells Motherboard.

Image: ArTIsT

Four months later, WikiLeaks published the now infamous “Collateral Murder” video, the first major release of classified information leaked by Chelsea Manning (then known as Bradley Manning), which thrust the secret-sharing organization into the public spotlight. The video showed a 2007 US helicopter attack in Iraq that wounded two children and killed their father, two Reuters employees, and a number of others. It wasn’t the video Katz had tried to open, though he didn’t know this at the time.

The file Katz tried to open, according to later testimony from Special Agent David Shaver of the Army’s Computer Crimes Investigative Unit, contained a different classified military video depicting a May 2009 US air strike near the Garani village in Afghanistan, which killed nearly 100 civilians, most of them children, according to locals. WikiLeaks has never published this video, reportedly because the group never succeeded in cracking the password.

Katz says at the time he downloaded the b.zip file, he had no idea what was in it.

“I didn’t really understand what the data was and what we were working with,” Katz says, “until all of these other [Manning] leaks came out and WikiLeaks started getting press.”

Katz’s involvement was significant because he was working at the time as a systems administrator in the physics department of Brookhaven National Laboratory, a Department of Energy (DoE) complex on Long Island that operates a particle accelerator, and is part of a collaborative project for analyzing data from the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland.

Asked if he downloaded the encrypted WikiLeaks file to his personal computer or his government one, Katz demurred.

“Let me think about answering this one,” he says. “I’m going to say ‘skip’ for that.”

But according to testimony at Manning’s hearing, investigators found the file and password-cracking program on his work computer. Katz was fired a few months after he downloaded the file, over “inappropriate computer activity.” Ironically, Katz says Brookhaven was unaware at the time of his connection to WikiLeaks, since none of Manning’s leaks had been published yet. Instead, Katz says he was fired for something more mundane.

“It appealed to the hacker ethos. The David-Goliath archetype.”

A few weeks after he downloaded the files, Katz says, a programmer working at Brookhaven suffered a mental health crisis over the Christmas break. The worker, whom Katz describes as an immigrant from Asia, had no family in the area. So when the lab closed for the holidays and everyone went home, he reportedly remained on campus alone. The extended isolation apparently triggered a psychotic episode. Katz remembers receiving a phone call from the worker during the holiday break and having a “nonsensical” conversation with him.

“I knew who was calling me and I knew where he was, but I didn’t know what he was talking about,” Katz recalls.

Katz says the worker set fire to his room on the Brookhaven campus, and when security arrived, he was spouting gibberish. Katz says his name came up in the conversation, though he’s not sure why or what the worker said about him. Katz and the programmer had discussed WikiLeaks in the past, but Katz doesn’t know if the programmer mentioned that to security.

“This is somebody that I had worked with, and [he] had asked at one point what was going on with my computer,” Katz says. But Katz didn’t think the worker knew that he downloaded a WikiLeaks file.

At some point after Katz returned to work following the holiday break—he can’t remember how long after—he says Brookhaven security approached him. Katz says they took his work computer and personal laptop, which he used to communicate in IRC rooms. The latter was encrypted, and Katz refused to hand over his password or sign a document saying he was relinquishing his laptop voluntarily.

“[T]his is probably what got me fired,” Katz tells Motherboard. “I wasn’t cooperating with counter-intelligence and because of that, it was akin to insubordination.”

Katz eventually got the laptop back, but was dismissed in March 2010—presumably, for simply having the password-cracking tool on his computer, since Brookhaven investigators wouldn’t learn what was in the encrypted .zip file until months later. (Brookhaven did not respond to repeated requests for information about Katz’s employment with the lab.)

Shortly after his dismissal, on April 5, 2010, WikiLeaks published “Collateral Murder.” Manning was arrested the next month after confessing to a hacker named Adrian Lamo that he had leaked hundreds of thousands of documents to WikiLeaks, and Lamo turned him in.

By September, Katz had moved on to a new job as a systems administrator with Tower Research Capital, a hedge fund company in New York, and had put the incident at Brookhaven behind him. But a series of events were unfolding that would soon bring it all back.

*

In July, Lamo had somehow learned of Katz’s attempt to crack the Garani video file and told Army investigators who were working the Manning case. They examined Katz’s old Brookhaven work computer, or images of it, and found evidence that he had downloaded the b.zip file as well as a password-cracking tool and had attempted to open the file—though they were unable to determine if he succeeded.

Katz remained oblivious to Lamo’s betrayal of him for many months. He was working a cushy job earning $75,000 a year with free meals, rooftop parties and five weeks of paid vacation. But he was someone who got bored with jobs fairly quickly and in early 2011 began looking for new work. He saw an ad for a job in Iceland with a startup called Videntifier, which developed technology for fingerprinting and identifying videos. He wasn’t interested in the job, but was curious about Iceland and saw it as a chance for a free trip. But after flying to meet with the founders that February, he was blown away by their technology and decided to take the job.

“I had been talking about living outside the US for a while,” Katz says. “And I’m fairly impulsive sometimes.”

Katz returned to New York in late February and after taking some time to think about it, gave notice to his employer, saying he’d continue to work a few more months before taking off. But on March 31, two weeks after giving notice, the FBI showed up at Tower. “I think what they saw was me flying to Iceland and back, and that freaked them out,” he says.

Given the timing of these events, there’s reason to believe Katz had been under surveillance since the previous July, when Lamo gave the feds his name. Assange and WikiLeaks had used Iceland as a home base in 2010 while preparing the Manning leaks for publication, and Katz’s trip there a year later must have looked highly suspicious. And three months before Katz’s trip to Iceland, US Attorney General Eric Holder revealed publicly for the first time that there was an “active, ongoing criminal investigation” and grand jury probe against Assange and WikiLeaks. The next month, the FBI served a sealed grand jury subpoena to a man named Andrew Strutt, to seize a server he managed.

Strutt, known in the wider hacker community as r0d3nt, was co-owner and administrator of pinky.ratman.org, a Linux shell server for more than 300 security researchers and technology enthusiasts. He was also a defense contractor. Strutt has successfully straddled the hacker and government communities for years, having hosted the IRC network for the hacker community 2600 while contracting for the military and government and also being a member of the FBI’s Infragard program, which fosters cooperation between the feds and the private sector. He tells Motherboard he tried to fight the subpoena but didn’t have the resources to do so, and ended up turning over the server to the feds.

“I refused to answer any questions,” Strutt says. “They threatened to either put me on the stand to the grand jury, for a crime that is unknown to me, and a person that is unknown to me.. or I comply with a very specific sealed legal process…. [H]undreds of hackers and users and security researchers trust me with their secrets. I will take them to my grave. I was not about to sit on the stand to a grand jury and have to answer questions about unknown crimes and persons.”

In a statement Strutt would publish online on March 30 after the feds gave him permission, he said the FBI was looking for information about “the activities of a particular user whose identity I am not aware of.”

It’s unclear if the file Katz tried to open ever passed through Strutt’s server, but Katz believes this was likely the case. Strutt says initially the feds thought he was responsible for the activity they were investigating.

“[W]hatever it was they were looking for, they thought it was me,” Strutt wrote in a message to Motherboard. Because of relationships he had developed through Infragard, Strutt says they called him initially instead of just showing up to seize his server. When he delayed responding while he sought assistance from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, they showed up at his work.

“[W]hen I explained to them via my lawyer, that there were 300+ people with accounts on that machine, and that I’m a ISP. It blew their mind. They had no idea other people had access to the machine,” he says.

He says the FBI promised he’d eventually be given a list of what they examined on the server, but they never did. It’s notable, however, that they were only interested in activity that occurred prior to August 2010, which was around the time Lamo informed on Katz. Strutt says he eventually figured out why the server was seized when he read an article about Katz’s role in the Manning case. He eventually got the server back, but not until October 2015. He tells Motherboard he had to sign another gag order to get the server. In a tweet he sent out when he got the server back, he referenced WikiLeaks, Katz and Lamo, essentially signaling to everyone in the community the reason his server had been seized.

On the morning of March 31st, 2011, the day after Strutt had published his initial note about the seizure, Katz says he arrived to his hedge fund job, opened the personal laptop he’d brought with him, then noticed three strangers walking toward him. He tells Motherboard he sensed immediately that something was odd, and got up to get a drink. That’s when he says one of the guys lunged at him, yelling, “FBI! You’re not under arrest!” while another one seized his personal laptop. It was the same netbook laptop that Brookhaven security had seized a year earlier and returned to him.

“This is how dumb I am,” Katz told Motherboard. “I’m still bringing around the laptop that had been given back to me, because I still want to IRC and do things not on the company workstation.”

Since he wasn’t under arrest, Katz suggested they talk in a conference room. “I think the second or third sentence out of my mouth was, ‘I need to speak with my lawyer,’” he recalled.

He recalls being handed a document containing the names of Assange, Manning and Jacob Appelbaum…

The agents told him they weren’t really interested in him; their focus was on someone else. His memory is foggy, but he recalls being handed a document containing the names of Assange, Manning and Jacob Appelbaum—the latter a friend of Assange and WikiLeaks who occasionally made public appearances on WikiLeaks’ behalf—but can’t remember if that occurred the day of the raid or later. If he helped them out, they said, they’d let prosecutors know that he’d cooperated.

“I said, ‘that’s great, if you can put that in writing I will hand it over to my lawyer and we’ll get back to you,’” Katz said.

By chance, Katz says he had a business card in his wallet from Rainey Reitman, an activist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, whom he’d met a month earlier at Shmoocon, an annual hacker conference held in Washington, DC. He excused himself to call Reitman and got the name of a defense lawyer in New York who could help him. (Motherboard called Reitman for comment, but did not receive a response in time for this article’s publication).

Katz’s meeting with the FBI lasted more than an hour, by his recollection. And during that time, Katz says his apartment in Brooklyn was raided, as was a house on Long Island that belonged to his girlfriend’s family. The FBI allegedly imaged his roommate’s laptop as well as other laptops in the apartment, and examined computers in his girlfriend’s home. Katz says his girlfriend saw an FBI agent take something from his car, which was parked outside her parents’ house; Katz thinks it may have been a GPS tracker.

Days later, someone identifying themselves as an FBI agent called Jason’s father and asked to talk, but the elder Katz refused unless a lawyer was present. The FBI agent hung up and never called back, Katz’s father recalled to Motherboard in a phone interview. Motherboard has agreed not to identify the elder Katz to protect his privacy. Agents also reportedly confronted Katz’s younger brother at work, convincing him to leave his job and go to FBI headquarters for what turned out to be several hours of intensive questioning.

“I didn’t involve a lot of people in what I did. So nobody could say with certainty anything if they were asked questions.”

Although he still had a few months left to work on his job at Tower, when Katz returned to his office after the raid, the hedge fund company fired him. (Motherboard called Tower Research Capital for comment, but did not receive a response in time for this article’s publication.)

Over the next couple of weeks, Katz says anyone he had more than a passing acquaintance with was approached by the FBI. His girlfriend was also subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury in Virginia, and agreed to go after securing immunity, but Katz says she didn’t know anything about his involvement with WikiLeaks.

“I didn’t involve a lot of people in what I did,” he explained. “So nobody could say with certainty anything if they were asked questions.”

After refusing to testify to the grand jury himself, Katz decided to proceed with his move to Iceland. Lamo has publicly stated that Katz ran to Iceland to avoid prosecution.

But Katz’s visa application for Iceland required that he pass an FBI background check. So while still under FBI suspicion for his involvement with WikiLeaks, Katz dutifully mailed his fingerprints to the FBI. He got a clean report back several months later and moved to Iceland in February 2012. He never asked the FBI to return the laptop they seized from him, fearing that doing so would renew the agency’s interest in his case. (Motherboard emailed the FBI for comment about their investigation into Katz, but did not receive a response in time for this article’s publication).

Eight months after making the move, he founded the Pirate Party with Icelandic politician and former WikiLeaks collaborator Birgitta Jónsdóttir, and a handful of other WikiLeaks supporters and activists.

“All of this stuff with the FBI forced my hand into following through on activist angles,” Katz said. “There was no going back at that point.”

Subscribe to Science Solved It, Motherboard’s new show about the greatest mysteries that were solved by science.