It wasn’t until age eight, when a teacher suggested she take art classes at the Frank Joubert Art Center in Cape Town, South Africa, that Lady Skollie actually began to enjoy life. Born and raised in the coastal city, she spent the years between six and 18 at a Model C school, a type of educational institution that was designated for white children until the end of apartheid in 1994.

Lady Skollie, whose real name is Laura Windvogel, was one of the first black students to attend the school. “It was the ‘in’ thing to do,” she says. “Until I joined Frank Joubert, I had no experience with black kids. Being at a Model C was hard and I felt like a traitor to my people.”

Videos by VICE

These experiences of growing up as a woman of colour in post-apartheid South Africa are at the core of Lady Skollie’s work, which is being exhibited for the first time in London at the show Lust Politics at Tyburn Gallery.

Her ambition is straightforward: “I want to make art that’s transparent. I’m not interested in art that’s buoyed up by its captions.” She’s always been this no-BS. Lady Skollie’s instantly recognizable practice presents the tenuous state of modern South African womanhood with large, beautiful canvases that are as strategic as they are stunning. “I don’t want people of colour and poor people excluded from my work,” she says. “That’s the point. I hate art that excludes a certain class of person because you have to read 14 pages of something to get it.

Read more: The Woman Making Art out of the FBI’s Surveillance of Her Black Panther Father

“That in itself is how the art space has remained so white in South Africa, because it’s made to alienate a new wave of gallery goers and art lovers. Especially people of colour. People of colour are like, ‘What is this shit? I’m not going to read 19 or whatever pages. I want to look at something that speaks to me and something I can feel without any bullshit.’”

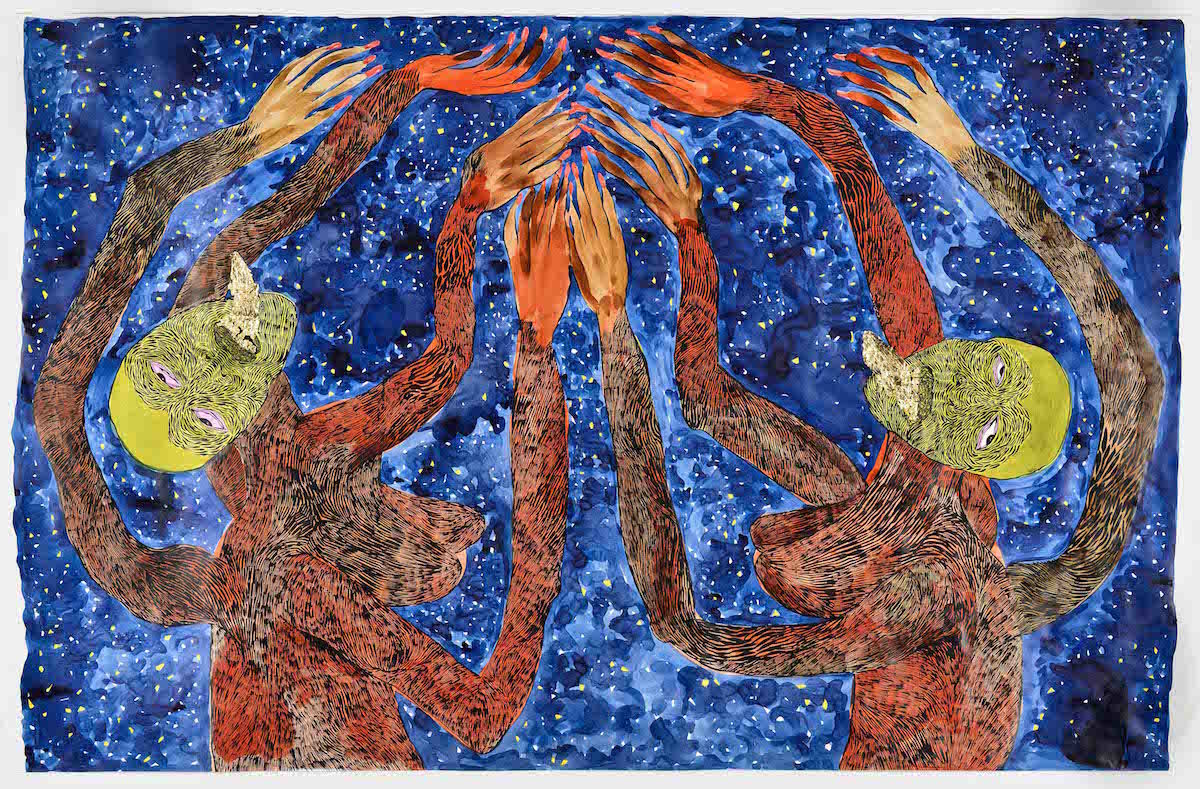

Her desire to draw attention to issues of race, class, sex and gender in South Africa underpins the entire Lust Politics show, featuring oil and paint canvases with names such as: They suck you dry, beware and Pink dick: sometimes I reluctantly reflect of all the times I’ve allowed my pussy to be colonised. They’ll suck you dry, beware has a special place in Laura’s heart: “It’s my favourite work in the whole show.” Its original title was Krotoa, named after the Khoi tribeswoman who served as a translator between her tribe and the Dutch colonists in the late 1600s.

“They’ll suck you dry, beware” (2016) © Lady Skollie, courtesy of Tyburn Gallery

“Krotoa was married to a Dutch man named Pieter Van Meerhorff,” says Lady Skollie, adding, “I say married very lightly, because colored women were playthings, really, and it reminded me of Model C Schools in South Africa now.” She feels deeply conflicted about her experience of attending the school; she felt a huge divide between what she describes as “her people” and the rest of the students, and sees parallels between the lives of Krotoa and present day South African women. “I painted her with a moon because I wanted her to be sainted.”

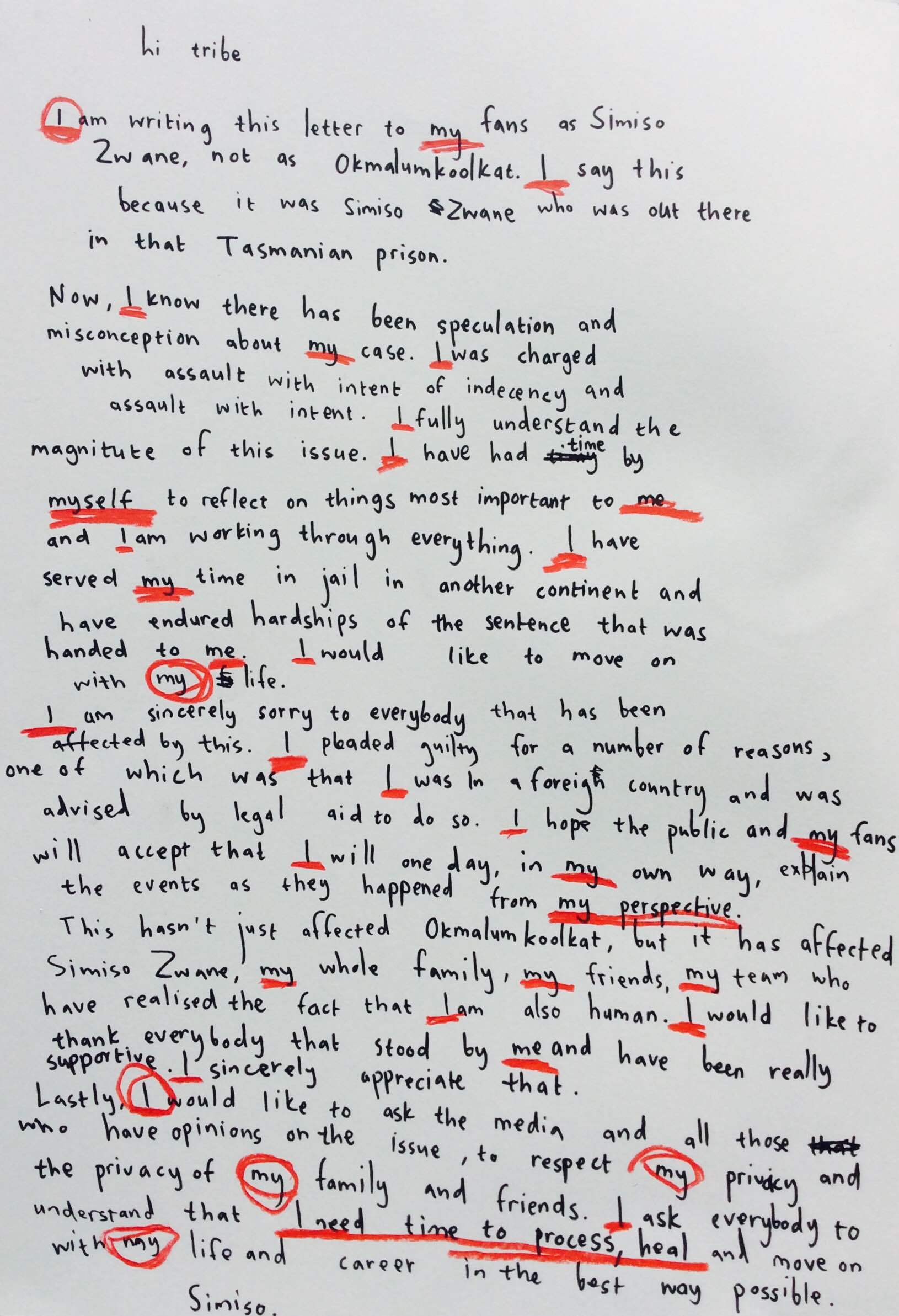

“#SorryNotSorry” © Lady Skollie, courtesy of the artist

Lady Skollie’s work also takes on what she describes as South Africa’s rape culture. The problem is so pervasive that, in one area near Johannesburg, one in every four women has been raped. “Most of those rapists will never see the inside of a jail,” she says. “Rape is seen as a trauma you should just deal with and get over.” The painting Cut-cut, kill-kill, stab-stab deals with the crisis. “Have you seen that painting A Few Small Nips (1935) by Frida Kahlo? That’s what it’s like in South Africa. The first thing the police say when you report a rape is ‘Was it your boyfriend or husband?’ And if it is, they’ll tell you they aren’t going to get this guy.”

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

The work #SorryNotSorry, a letter mimicking the apology of South African musician Simiso Zwane after he was imprisoned in Tasmania for sexual assault, deals with the victim blaming that survivors face when they come forward to report their attack. “There’s no accountability for rape. People would rather not have an awkward moment at the club or have their friend roofied by someone that they know because, ‘How can we share a bottle of Moet if not?’”

“Passion Gap: a selfportrait of the artist wrestling with her daddy issues; reaching misguidedly for the validation of men” (2016) © Lady Skollie, courtesy of Tyburn Gallery

What she finds disheartening is some of the attitudes of art collectors interested in her work. “I’ve had people buy my work before, then try to return it because their husband says they can’t have a painting with a dick on it. But that’s the thing with tabooism [sic] in South Africa, people would rather entertain a rapist in their house where their child is, than have a painting on the wall that questions rape culture itself.” She finds challenging these problematic attitudes cathartic. “Making art is theraputic for me, and I like to work quickly, it’s immersive. If I spend more than a week on a work, I hate it.”

“Lust Politics” installation view at Tyburn Gallery, London. Photo by Lewis Ronald, courtesy Lady Skollie and the gallery.

In lieu of police action, Lady Skollie is one of South Africa’s most outspoken cultural figures on this crisis, using her visual art, her super-smart Kiss-Tell podcast, and Kaapstad Kinsey Sex zine—which she started making in 2013 and where she developed her distinctive painting style—to start conversations about gender abuse that police and the government simply will not have. A couple of years ago, Lady Skollie became well-known in Johannesburg—where she now lives—for hosting racuous sex parties that brought together a mix of artists and members of the public. In reality, she’s only thrown three: “Yeah, I feel that I had to play the role of the sexy artist for such a long time. It’s nice to be free of that now.”

Taking on such serious problems in her work can be exhausting and to combat burnout, downtime is important. “I go and have my nails done. I might bite them off a week later, but it’s more about the experience of having them done that I like.”

“Lust Politics” installation view at Tyburn Gallery, London. Photo by Lewis Ronald, courtesy Lady Skollie and the gallery.

Her prolific work and outspokenness mean that a lot of people want to take her down a peg or two; in the past, people in the South African media have implied her looks and her work are one and the same. Lady Skollie remains unphased by criticism of her art or politics.

“This art critic Lin Sampson once suggested that maybe my looks had something to do with the success of my work,” she says, then laughs. “Whatever, bitch!” And while she says she also gets harassed on social media every day, she’s also more than capable of shrugging it off. “The insults aren’t that bad,” she says. “I mean, people with mash potato as brain aren’t that good at dissing.”

Lust Politics is on at the Tyburn Gallery until 4 March 2017.