This article is part of a special series on the intersection of guns and games. For more, click here.

America is finally having an ongoing conversation about gun violence. In the wake of last month’s school shooting in Parkland, Florida, and driven by the energetic political action of countless students across the country, it feels like there could be real regulatory action taken for the first time since the Federal Assault Weapons Ban went out of effect in 2004. Unsurprisingly, those that would prefer to dodge such regulation have, in searching for an alibi for gun violence, pointed again towards video games.

Videos by VICE

In the weeks that have followed, old debates have sparked new and classic scapegoats have been pushed again to cover for the nation’s inability to address a root cause. The Trump administration held an unproductive meeting with members of the games industry, then released a supercut of violent game moments. Nonprofit group Games for Change answered with their own counter video (to limited effect). Experts have weighed in via op-eds and personal essays across the enthusiast press and in mainstream publications.

Yet there is something else here too, something more than scapegoat-ism. Video games do not lead to direct violence, we believe that firmly. But that doesn’t mean that the way guns and violence are portrayed in our favorite hobby cannot test our consciences or that we cannot be critical of their depiction. Across social media, developers, players, and critics have tried to work out their personal positions in this messy intersection of culture and violence. That messiness is what makes these conversations important. It is valuable to dig into those conflicting feelings, to try to understand our particular dilemma as lovers of a medium in which guns are the uncritical device on which so much action turns.

All of this why, ahead of this Saturday’s March for Our Lives, Waypoint will be running a handful of stories about guns and games. We don’t have a fancy name for this week, but if you click here you’ll be able to keep up with every piece tackling the topic. Some of these pieces will be reported by Waypoint’s own staff and others by some of our favorite freelancers, but all of them are taking seriously the idea that guns and games have a relationship worth exploring.

That is where I planned to end this note. I hoped to let the work of our incredible writers speak for itself and for me. And then, on Saturday morning, I learned that a close family friend—someone who I grew up calling my aunt, who aided in raising me, who was family for my mother when others had turned away from her—was killed late last week in a tragic and cruel act of gun violence. It is something I am still processing, something that I’ll likely be working through for a while. But it made me feel like a coward to not address the topic myself.

So, here is what I think: Guns are a shortcut to violence, and violence is a powerful thing.

Great art doesn’t ignore violence, it actively explores the nuance of its power, using it as metaphor, as catalyst for major plot development, as the expression of a climactic release of tension. In the real world, the complexity of violence is even greater: A real appraisal of violence demands you contend with how it has shattered lives, yet also how it has protected them; how it has been a tool in the struggle against oppression, yet often works (whether performed or threatened, whether direct or indirect) to maintain the most tyrannical status quo.

But guns in games rarely carry the power of real violence. Instead, they gesture at power, the way a flexing muscle might suggest the possibilities offered by bulging biceps yet prioritizes first and foremost the pose. And as good critics, clever designers, and engaged players, we get very good at examining the pose. We talk about good gunplay, tactical complexity, and visceral action. I tweet about my love of the reload animations of Hunt: Showdown, talk on the podcast about the joy of Destiny’s headshots, I open my preview of Far Cry 5 by assuring you that yes, “the guns feel good.”

It’s funny. We never say how good the violence is.

There is a memorable section in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book-long letter to his son, Between the World and Me, in which he describes the reach, cost, and reverberations of the death of his childhood friend, Prince Jones, who was shot to death by a Maryland police officer in a case of “mistaken identity.” But there is another version of that passage, which he adapted for an online essay ahead of the book’s release, which explicitly expands the scope of his analysis. He writes:

Always remember that Trayvon Martin was a boy, that Tamir Rice was a particular boy, that Jordan Davis was a boy, like you. When you hear these names think of all the wealth poured into them. Think of the gasoline expended, the treads worn carting him to football games, basketball tournaments, and Little League. Think of the time spent regulating sleepovers. Think of the surprise birthday parties, the day care, and the reference checks on babysitters. Think of checks written for family photos. Think of soccer balls, science kits, chemistry sets, racetracks, and model trains. Think of all the embraces, all the private jokes, customs, greetings, names, dreams, all the shared knowledge and capacity of a black family injected into that vessel of flesh and bone. And think of how that vessel was taken, shattered on the concrete, and all its holy contents, all that had gone into each of them, was sent flowing back to the earth. It is terrible to truly see our particular beauty, Samori, because then you see the scope of the loss. But you must push even further. You must see that this loss is mandated by the history of your country, by the Dream of living white.

It was when I let myself explore my most specific memories of the family friend who was killed last week that my grief is felt most acutely: The warmth and patience of her voice as I chattered endlessly as a little boy. The fuzzy clicks of her TV as it warmed up, the animated visage of Batman appearing in time. The smell of my own sweat as I visited her with my mom after my taekwondo class. Her commanding posture as a poet, so unlike her more reserved stature at home.

It is this particularity of death (of all pain, all harm) that gives it power. Violence does not only occur between the involved parties. It ripples out into past and future. It crystallizes the steady streaming of context, bringing social history and individual mundanity into frozen formation.

Great art understands this and follows suit. It is why, in describing the horrific, yet loving violence at the heart of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, the protagonist pauses to recall that “the yard had a fence with a gate that somebody was latching and unlatching.” It’s why Kendrick Lamar captures the violence of self-hate in “u,” by describing his confidence (and his body) “breakin’ on marble floors,” his own voice splintering on top of dueling horns and ambient bass rumble. It’s why the first death in Alien doesn’t happen in a clean, forgettable infirmary or one of the featureless hallways of the Nostromo, but on top of mess hall’s familiar and cluttered dinner table.

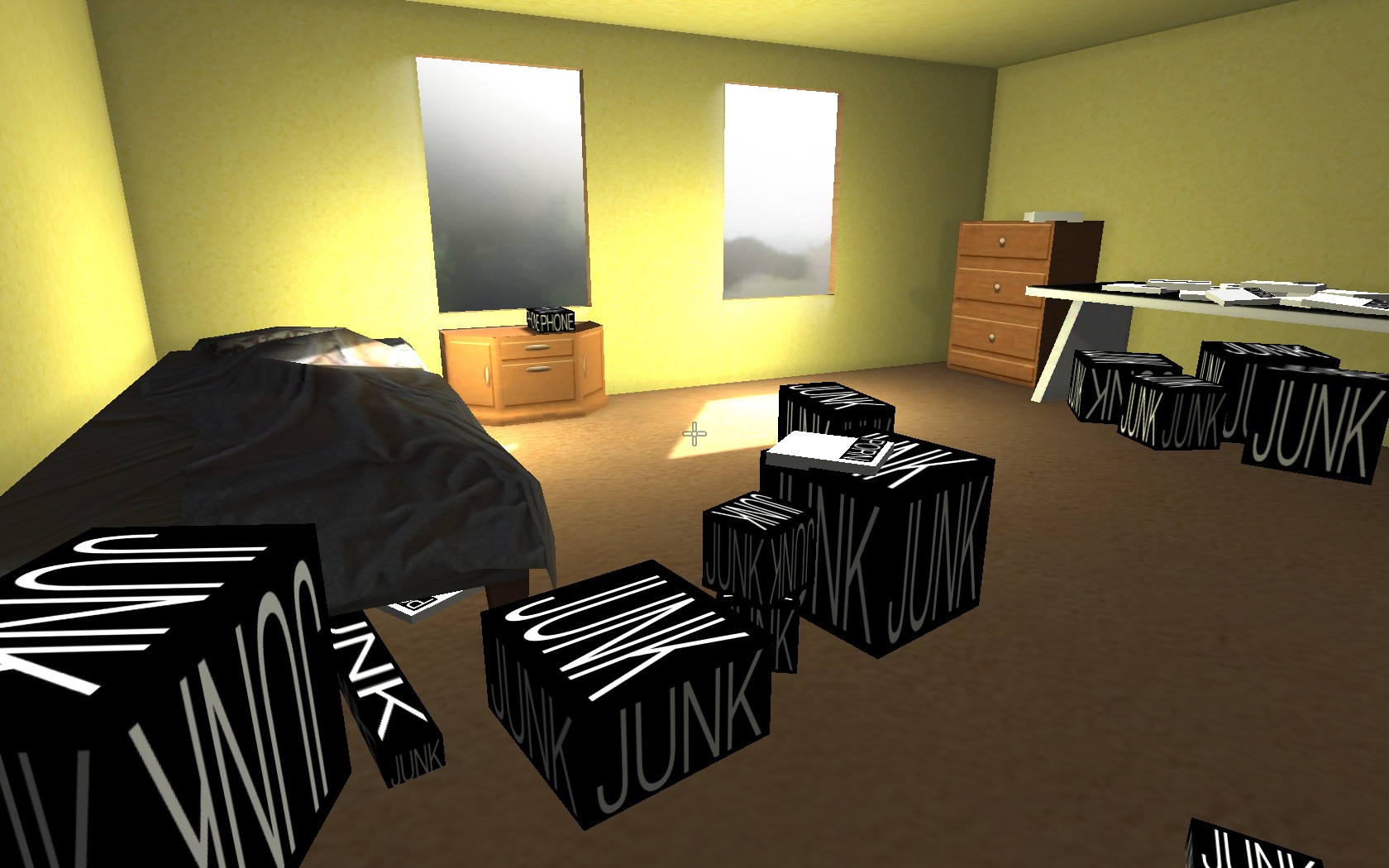

It is this particularity that is so often missing in video game violence, and it is that lack that deflates the power of guns in games. In big budget action games, and especially games that give the player guns and plentiful ammunition, violence is cheap and endlessly repeatable.

It is rare in these games that violence even feels like an act, it is more likely to be a mode. Game heroes slip between narrative vignettes and 30 minute long gunfights in which no particular enemy is distinct from the rest, reduced to hurdles on a track. A muscle flexing.

This is partly why I’m so interested in the cases where memorable, violence bubbles up inside of video games. Many of these examples predictably come via independent games like Amy Dentata’s 10 Seconds in Hell, which captures the frantic horror of domestic violence without ever depicting the event itself. Wolfire Games’ Receiver, takes the opposite tact: Unlike most first person shooters, it focuses on the raw mechanics of gun operation, pushing the fetishization all the way to paralyzing terror.

In the AAA space, where games sprawl across dozens of hours, where violence-as-mode is the selling point, instances of memorable gun violence are much rarer. The secret ending of Red Dead Redemption comes to mind. Most of my experience with PlayerUnknown Battlegrounds‘, which makes each death an event. But it’s telling that the clearest example I have of a big budget game engaging with this particular sense of violence is one that I created for myself by playing with my own rules: I still haven’t forgotten William Jones, the eleventh person I killed in Ubisoft’s Watch Dogs.

Some of the articles coming this week will be about other people who’ve brought their own rules about violence to bear in games. Others will look at games that take violence seriously—even when they’re playful and joyous in doing so. A couple will address the overlap between real world guns and the ones in games. I’m excited for you to read all of them, and I’m also incredibly curious about your own feelings on this issue, so please, visit this thread over on our forums and share your own experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

Most importantly, though, I hope this week encourages you to play critically. We hop so easily from sci-fi battlefield to campy train heist to tactical simulation, and somewhere in is where violence shifts to “combat.” I don’t know that that is changeable behavior, or even that it is fundamentally a bad shift, but I do think we’re better for being aware of the moment it happens.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Studio Trigger -

Collage by VICE -

AEW -

Screenshot: Hopoo Games