On April 9, 1860—157 years ago this Sunday—the French inventor Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville created the first sound recording in history.

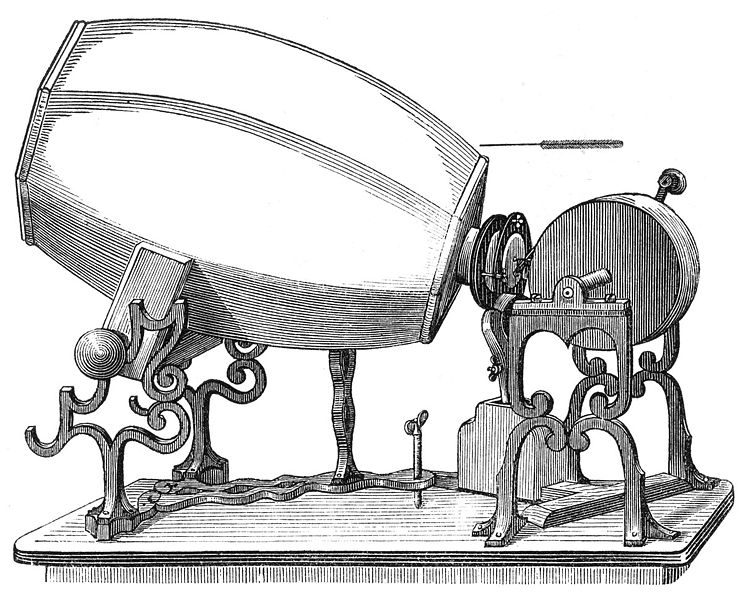

An eerie rendition of the folksong “Au clair de la lune,” the clip was captured by Scott’s trademark invention, the phonautograph, the earliest device known to preserve sound. You can listen to a copy of this inaugural deep cut below, but be warned, Victorian-era warblings are every bit as creepy as you’d expect.

Videos by VICE

Though the high pitch of the song evokes a child singer or a female soprano, some historians think it was sung by Scott while he was conducting experiments with his device. His voice may be pitched higher, Chipmunk-style, due to the translation of these early records into modern audio files, a process kickstarted by interdisciplinary sound experts in 2007.

Until this past decade, the clips recorded by Scott existed only as visual representations of sound vibrations, transcribed by a stylus onto fragile paper surfaces blackened by lamp soot. With his phonautograph, Scott was trying to artificially reconstruct the anatomy of the human ear in order to produce visual images of sound waves for research and preservation.

Read More: Behold the Ocular Harpsichord, the Laser Light Show of the 18th Century

Scott did not consider the prospect of subsequently playing back these sounds. That milestone was claimed instead by Thomas Edison’s phonograph, which debuted in 1877. Where Edison was intentionally projecting his voice into the future, Scott would probably have been surprised to learn that in the early 21st century, a group of scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California would find a way to bring his recordings to life.

Led by audio historian David Giovannoni, this project focused on the particularly well-preserved phonautograms Scott made in April 1860. These papers were scanned and processed with a virtual stylus, allowing project scientists to stitch together 16 recorded tracks into the short, haunting clip.

“It remains the earliest clearly recognizable record of the human voice yet recovered,” according to First Sounds, the informal collective of audio historians and scientists who cracked this sound code.

Today, we live in a new golden age of DIY sound recording and visualization, defined by the proliferation of podcasts and user-friendly audio-mixing software. But this distant voice from the past is a reminder of the pioneers of acoustic engineering, and the ingenious ways in which they converted fleeting sounds into permanent audio files—sometimes completely by accident.

Subscribe to pluspluspodcast , Motherboard’s new show about the people and machines that are building our future.