This article was originally published on Noisey’s UK site.

At a panel late last year titled “Is London Too Rich to be Interesting?” Saatchi-approved sculpture pioneer Gavin Turk, now 48-years old, was asked a simple question by an audience member: “If you had your time again, from now, in this London—with no grant, and no time to spend swimming around for patrons—how would you do it? Would you still be here? Would you stay?” Prior to that, he’d indulged the audience with stories about how a glorious and multi-faceted London of times past had given him the opportunities, freedom and inspiration he needed to explore his art and self, and become who he is, but he can’t help stutter on this question for some time, before coming to a long winded conclusion which I’ll simplify here: No, probably not actually.

Videos by VICE

Things have never been easy for creative types in the city, that’s kind of the point. But they’ve also never been this bad until very recently. Only in the late 90s into early 2000s, the city was fostering multiple vibrant music scenes, each one representative of the young people that fuelled it: from grime in Bow, to indie in Camden, to dubstep in Croydon, to artrock in New Cross. To have that many young people all maintaining so many seperate, vibrant and concurrent scenes in London now seems impossible.

London used to offer artists a means to flourish, which was why it would always be uttered on the same subcultural whispers as New York and Berlin. By hook or by crook, musicians could not only eat, live and work, but also make enough to record, buy equipment, tour van gas, expenses, managers, CDs, drugs, pot noodles. There was cheap housing if you had the balls to rough it out (it often came with rats, shit landlords and toilets that coughed sewage, free of charge). Recording studios could be found in the middle of town that hadn’t yet been forced to close, or pander their diaries and costings to big money block bookings—so a young band or artist could get a few hours in front of a half decent mixing desk for not an unrealistic price, without going on mythological quests to Zone 8. The city even had a visible ladder of progression, its venues would guide a rise, all the way from shithole basement to 200 cap club to decent sized concert hall. But the most important thing the city had was time. Obviously there was no eternal well of opportunity for workshy shitbags, but it wasn’t so unrealistic for an aspiring musician to work three or four days a week in a dive bar, and spend the rest on building their dream. An artistic balance could be achieved, where your work was just work and your talent was your focus, without simply consigning yourself to waste.

Photo via LondonIsChanging.org

Is Tropical were one of many bands who took advantage of the city’s charms and loopholes, throwing their dice at London’s heaving squat scene around 2007. “When we discovered living in squats was doable, it was perfect,” explains lead singer Simon Milner. “Suddenly, everyone had the time to get on with what they loved. If you just have to work for rent then you have to work five days a week, but as an artist, you have to buy your equipment too, whether it’s paints, instruments, or jewelry. It’s expensive, so an opportunity to live for free, yeah, in horrible conditions, was vital.”

Photo provided by Is Tropical.

Their now famous South London squat was called The Toilet Factory, and homed themselves, Shitdisco (together, then known as Ratty Rat Rat), and The Metros (some of whom went on to become Fat White Family). It was one of many in the city; including others like the notorious Squally Oaks, which housed early formations of Metronomy, !WowoW! squat in Peckham, and also 78 Lyndhurst Way.

“Down in South London there was a load of us. A lot of artists like Matthew Stone, the writer Karley Sciortino. So it was a really big scene. From the outside it probably looked like everyone was just wasters, but that’s where you socialized, collaborated, and made your connections.”

South London band Breton utilised a guardianship scheme for the first part of their career, where tenants are welcomed into otherwise abandoned buildings for next to nothing, to basically keep the building’s blood pumping. They landed themselves in an old bank in Elephant & Castle, which they dubbed BretonLABs. “It was like Stalingrad most of the time,” they tell me, and they all slept in a wedding marquee with electric heaters in the center of the space. “When we got signed, we bought massive coats” says lead singer Roman.

Members of London band Breton, on the roof of their South London squat

Still, it was a place they could live, film, and record for next to nothing. Another girl in their building ran her theater company from home, stacking her space with props. A different tenant was the filmmaker Ian Pons Jewell, who’s now an esteemed director, he made the video for Naughty Boy’s “La La La” and scooped the 2013 MOBOs and Best Director at the UK Music Video Awards as a result.

But in 2012, the Conservative government made squatting in a residential building in England and Wales a criminal offence. What was previously a civic matter, became a police matter, meaning people could be rapidly evicted. An old bank in the middle of Elephant & Castle might not sound like a residential building, but because one small room was once deemed the bank manager’s sleeping quarters (in the 80s), it was enough to get the whole building classed as “residential,” and Breton, plus 15 other residents, were evicted so it could be demolished. There’s something poetically cyclical about how such a capitalist construct, as an in-office living space made for bankers to ensure they work excessive hours into the night, was still managing to do its bit for inequality, even in its dilapidated state.

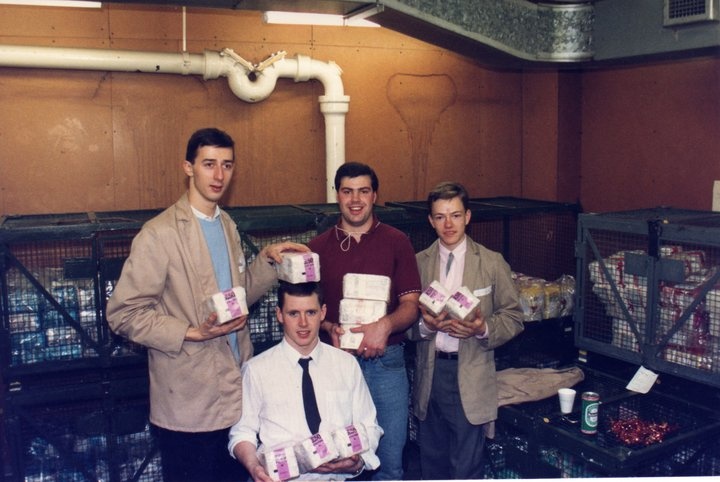

Men holding stacks of cash at Breton’s bank, back when it was actually a bank in the 80s.

The decimation of London’s art squats is a metaphor for the city’s recalibrated attitude towards art, and 2015 London has all the spluttering symptoms of a city hurtling towards cultural void. Investors pick up housing estates as if they’re glass ketchup bottles, turning them upside down and smacking the bottom until all the inhabitants fall out. Wages have stagnated, living costs have soared, rents have rocketed, venues are being methodically demolished, 150,000 of us are working two jobs, and everyone with a creative one is considering a move to Woodford.

Over in the fallows of central London, bankers body pump to “Everybody’s Free” at morning raves, each new bead of sweat more resinous than the previous, as last night’s cocaine residue is taxied out of their bloodstream. The same month London Mayor Boris Johnson launches his #BackBusking campaign, his police force are heavy handedly arresting musicians in broad daylight for doing just that in Leicester Square.

We’re told to tolerate this, and that it is a means to an end because—grin emoji, thumbs up emoji—London’s output growth is BETTER THAN EVER! The problem is, the burgeoning riches of a city don’t necessarily correlate with its art and creativity. Cities like Lisbon, where new strands of Afro-Portuguese electronic music seem to sprout every six months, or Atlanta, where trap has supernova’d in every direction, aren’t teeming with invention because of a influx of billionares, high density penthouse monoculture or chains of cold brewed coffee shops. Berlin’s progressive arts scene is in part thanks to the progressive politics that frame it, and they’ve addressed their soaring costs by becoming the first German city to introduce rent capping. So, it’s no surprise that in London, the unhindered boom in the city’s wealth hasn’t exactly chimed with an explosion of subculture and youth movements. You only need to look at the cities London is now mentioned alongside: digested baked bean shells like Singapore, or sanitized 1-percenter city-state toy towns like Monaco, to get a feel for its aspirational trajectory. Tell me, who was the last shit hot beatmaker from Monaco you faved on Soundcloud? These days, for most normal musicians to survive London’s demands, their employment must become their everything, their music: a mere hobby.

“In the last few years,” explains Roman of Breton, who coped with the demolition of their bank by moving to, you guessed it, Berlin. “They have done their best to paint these pictures of crusty squatters, who go and smash up these buildings, but it’s not like that. Yeah, we were basically living like heroin addicts without the perks of heroin. But that made the band possible! All the things that a Londoner had to pay for, that could really attack our time and freedom, we felt liberated from.”

Breton’s bank at its peak.

The process of “artwashing” has become a tried and tested tactic of London developers, and you can see it happening now at the Balfron Tower in Poplar. It’s an eerie coincidence that a building which looks so much like JG Ballard’s description in High Rise, is now becoming a similar social experiment. The premise of artwashing is simple: developers snap up supposedly neglected former social housing areas (original tenants of which are usually forced out) and encourage artists, musicians and creatives in as property guardians, just like Breton’s situation, on short term deals which usually involve 24 hours eviction notices. The presence of creative types gives the formerly neglected area a lovely glistening gloss, a quick fix appearance of transformation. Then, before an artistic community is given an opportunity to actually root, it is kicked out, so the properties can be remarketed to wealthier buyers who wouldn’t have been interested in the first place. “By highlighting the new creative uses for inner-city areas,” wrote Feargus O’Sullivan for CityLab, “it presents regeneration not through its long-term effects—the transfer of residency from poor to rich—but as a much shorter journey from neglect to creativity.” This is why Grayson Perry calls artists “the shock troops of gentrification.”

Photo by Chris Bethell.

The tricks and charms, that made London such a colorful city, have been chemically bleached, and who knows where to get a leg up anymore. I talked with the four girls that make up grunge-tinted indie band The Big Moon, specifically their lead singer Juliette, who I’d been told was scraping by on a part time shop assistant job around their gigs and rehearsals. They packed Corsica Studios for a single launch party recently, and were championed by Annie Mac on Radio 1 two weeks ago.

“I am at my absolute limits right now,” explains Juliette. “It’s not that I feel forced out by London – more like I’m always racing to catch up with the city, but it’s lapping me. You pay your rent, you eat less. You have two rehearsals, you don’t go out. But I haven’t been out since New Year’s Eve. I’ve always felt like I needed to be in London, as a musician, but as smaller venues seem to be closing down all the time, and so many clubs are using these dirty promoters that keep all the door money and pay you £1 per 5 people who come… you just start to feel exploited.”

The Big Moon.

That feeling, like there’s no time to pursue anything but wage-paying, rent-solving employment in London, is another factor working against musicians, one that political writer Ewa Jasiewicz dubbed

“time poverty” in her post-election piece. She identified it as a byproduct of the intensification of labor and rise in cost of living, two things London has by the butt load. “If we can’t have our own time to organize, we can’t organize, we can’t meet each other, we cannot find each other” she wrote, highlighting how we’re kept too distracted and busy to unify and discover our collective politics. But the other thing that cannot flourish under these constricts is art, and with regards to this article: music. Real music by normal people, not Bedales alumni, or kids with grants, parents in finance, or major label development deals. “Middle-class bands are the most content, tasteless cunts around,” Young Fathers’ G Hastings told the NME back in March, and although that’s a bit more direct and caustic than I’d ever phrase it, he followed that up with one undeniable truism: “Working-class bands have been eradicated.”

The growing impossibility of starting from the bottom and actually making it in today’s music industry is mirrored by the ugly portrait of successful British music. As Gavin Haynes wrote for Noisey in January: “We are living in an age where a certain kind of lozenge-folk have come to dominate. It’s no longer just the children of lawyers and architects. It’s the kids of the balls-out elite. Sam Smith’s £500k-a-year banker mother. The Mumfords—Winston Marshall’s dad being the chairman of one of the country’s largest hedge-funds.”

The pursuit of funding for artists trapped at this level is the much publicized but largely artificial carrot dangled up front. The British government made a song and dance out of their £2.5 million slush fund for musicians last summer. In Kafkaesque fashion, bands were encouraged to fill out endless reams of forms, usually to discover that they were eliminated in round 3,843, and the money would be going to The Wombats.

Harking back to that question posed to sculpture artist Gavin Turk at the very beginning of this piece: if these artists had to start again, right now, would they do it in London? Would they stay? Is Tropical are currently trying to move to the French countryside because even with occasional flights for London gigs and meetings, it’s working out cheaper. Juliette from The Big Moon is considering a move to Rotterdam because: “I dream of moving there and paying literally half of what I pay here and think of all the time and space I could indulge in there… London gives me less and less.”

But should musicians be encouraged to stay and fight for the culture of the city? I asked London rapper Akala this question. Not only is he a longstanding local who’s lived in his area for six years, and a UK rap artist on album number five, but he’s also fiercely outspoken on the politics and society of the city. “Yeah I do think they should stay, but I’m not judging anyone who can’t afford it anymore. It’s London’s loss. All this sanitization and gentrification that is happening to all of the cultural spaces that were different, that were diverse, that produced the cultures of music that people loved. People want to love jungle, hip-hop, garage, and the various other cultures that have found spaces in London. But it seems like they want those spaces without the people that produced those forms of music.”

At the end of the day, choosing to be an artist is, to many extents, a luxury, and nobody’s saying things should be easy for those who choose it as their career—but it shouldn’t be impossible. The saying goes, a true artist will always find a way. But as London’s playing field becomes more like booting a ball up Everest, it feels like that “way” is fast becoming the M1. The utopian dream is that London’s accelerating drain becomes the benefit of the UK’s other cities, like Glasgow, Newcastle, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, as more London artists flock there for more flexible living, because why settle for Zone 8 rent prices when there are huge and beautiful cities elsewhere? And as the digital revolution continues, more homegrown artists will be deterred from the romantic notion of coming down to London to “make it,” because unless you’re established, or things change, you’d be a fool for doing so. As Roman from Breton says if he had to do it all again, “I’d find a cold abandoned metal factory in Sheffield, because all you need to be a musician these days is space, time, mates, broadband… and a big coat.”

You can follow Joe Zadeh on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Sherry Rayn Barnett/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images) -

Tromsdalstinden, Tromsø's 'magic mountain'. All photos by Frank L'Opez -

Abby Lee, chef-owner of Mambow Malaysian restaurant in East London. -

Collage by VICE