This article appears in the August Issue of VICE Magazine

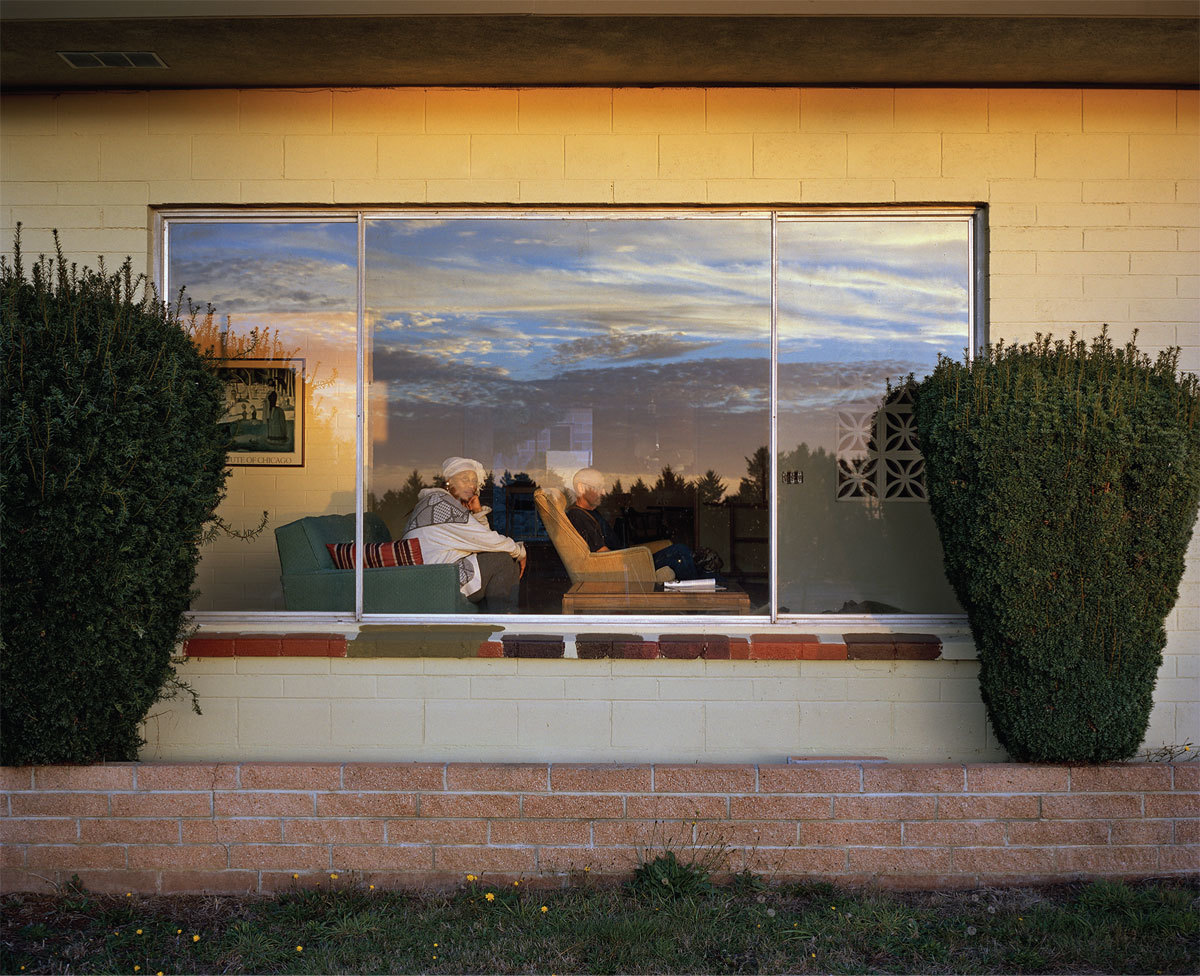

Curran Hatleberg currently lives somewhere in North Florida between his car and friends’ couches. This nomadic condition is familiar to the 33-year-old: He spent six months roaming the Southwest in an Airstream trailer, until that ended and he moved on to Florida. His photographic process has always involved this drifting—driving with no destination until he encounters a scene that resonates with him. “There’s something that just feels like I need to get out of the car and walk,” Hatleberg told me. “Maybe it’s as simple as there’s a bunch of people out and about. I just start walking up to people with my camera displayed and introducing myself, and then I spend time with them.” This contributes to the uncontrived immediacy of Hatleberg’s pictures: “After a certain point people become numb to you and dissolve back into the flow of action they were engaged in when you first approached them.”

Videos by VICE

Hatleberg’s forthcoming first book of photographs, Lost Coast, puts this patient observation on display. Last year, Hatleberg decided to take a short break from his wandering to teach photography at College of the Redwoods in Eureka, California, and photograph the residents and landscape of the small towns of Humboldt County. “I’ve never been attached to one specific place for that long,” he said. “It really changed the way that I was working.” Fitting, then, that the pictures in Lost Coast neglect the impermanent population of Eureka—the thousands of dreadlocked neo-hippies and free-wheeling liberal arts school graduates who drift through town on their way to trim marijuana on any number of the weed farms Humboldt Country is famous for. Instead his pictures focus on the town’s permanent residents. Many of these individuals are fiercely independent, choosing isolation behind the so-called “Redwood Curtain” despite bleak economic conditions in the region.

A psychoactive tinge does creep into the photographs nonetheless, largely thanks to the scale problem created by the outsize nature of the old-growth forests and the frequently misty, atmospheric light of the Northern California coastline. “The landscape there is very psychedelic,” Hatleberg explained. “There is a majestic, prehistoric quality—this grandeur of nature that I was completely captivated by as a stage. It’s this larger-than-life presence that’s always towering over you—redwoods spilling off cliffs down into the Pacific Ocean. It’s the most beautiful thing you can imagine. Yet it is a place of polarizing extremes. Underneath the grandeur of nature the familiar struggles of small-town life are found—drug abuse, economic hardship. People exist in a kind of dream state, propped up by the mythology of the Pacific Northwest. Everything is seen through fog and nothing is fully revealed. Even now, the place is a mystery to me.”

—MATTHEW LEIFHEIT

Curran Hatleberg is the recipient of a 2015 grant from Magnum Foundation’s Emergency Fund and the 2014 Individual Photographer’s Fellowship from the Aaron Siskind Foundation. The following photographs are a selection from the more than 60 pictures in his first book, Lost Coast, which will be published by TBW Books in September.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Play! NANOO -

Mystic Aquarium/Facebook -

Photo: Abeer Ahmed/NurPhoto via Getty Images)