The best way that Lucy Sante can explain the past year of her life is that it was the culmination of six decades in which her subconscious mind was quietly working out an intractable problem. Sante has known on some level since childhood that she is a woman. But like many older trans adults, she subsumed that knowledge. She circled around it in her private ruminations and secretly pored over what little she could find about trans identity, but largely kept it under a psychological lock and key, partitioned from her everyday life as best she could.

“I didn’t bury it,” she said recently. “I dismembered it and scattered the parts. I forbade myself from linking them together.”

Videos by VICE

Then, quite suddenly, last February, she knew what to do.

“It was exhilarating but weird,” Sante, 67, said by phone in early November from her home in Kingston, New York. “So much of what I’ve felt in this whole process has been like I’m being guided.” Not in a spiritual way, she added. “I don’t believe in woo woo. But I recognize this feeling. It’s analog to an experience which I’ve previously had in the course of writing. It’s my subconscious. My subconscious has been working on this game plan without my knowledge for the last 50 or 60 years, and now it’s executing.”

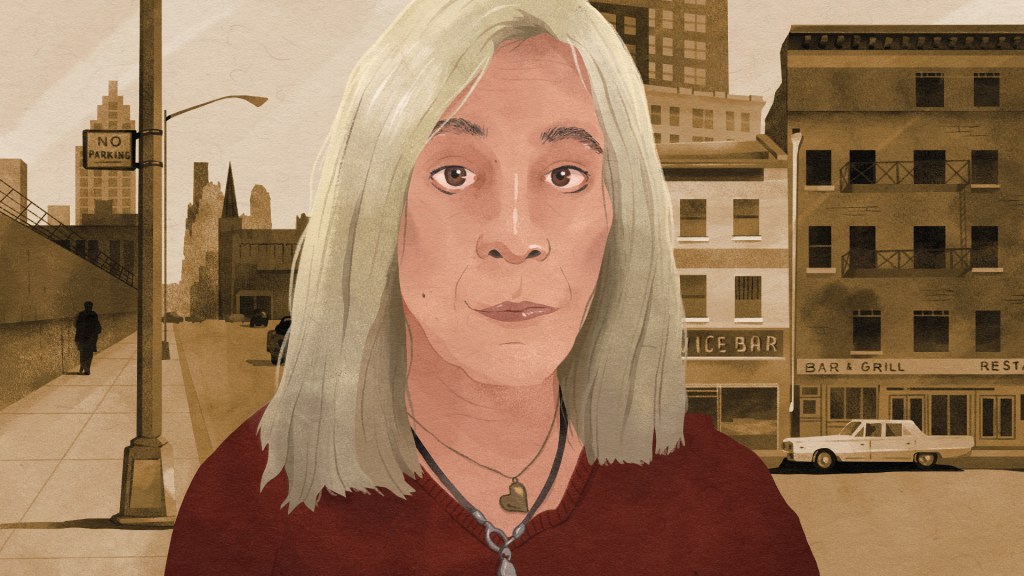

Sante is a celebrated author, essayist, and teacher whose Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York is one of the most revered books ever written about any city, an exhilarating portrait of the gangs, bars, brothels, and street cons that made up the city’s so-called “underclass” at the turn of the century. She gave the same street-level view of another famed city in The Other Paris, and built up a gorgeous, wry, deeply observed, and relentlessly original body of work across essays about photography, music, pop culture, punk, poetry, visual art, and the changing fortunes of the New York and particularly the East Village, where she spent many of the most consequential years of her life. For that entire time, she presented as male; she’s currently promoting a new book, Maybe People Would Be the Times, which bears her previous name. (Her next book, Nineteen Reservoirs, is set to be published this summer.)

And then, as she wrote in an essay for Vanity Fair that appeared earlier this week, came the app that would change her life.

“My subconscious has been working on this game plan without my knowledge for the last 50 or 60 years, and now it’s executing.”

“My egg cracked in the middle of February,” Sante said, using a term for when someone acknowledges to themselves that they’re trans. She’d gotten a new phone, and one of the first things she thought of was FaceApp, the face-editing app that shows users how they’d look if they were younger, older, or—as would be crucial here—presenting as a different gender.

Sante had tried it with a previous, clunkier phone and found the results disturbing, a vision of herself that was, as she put it dryly, “bald and missing half its skull.” The new phone had a better camera. She tried again.

“I took a picture of myself and gender-swapped it, and then set about feeding in every single photo of myself I had.” Unfolded before her was a lifetime in which she could’ve been seen as a girl and then a woman, her memories revisited with her external appearance and her inner sense of self finally aligned. The effect was overwhelming.

“I didn’t weep or jump up and down,” Sante said, but she was wholly undone. The next two weeks, before she told anyone else, “were so cataclysmic I can barely remember anything.”

At the beginning of March, she came out to her therapist, partner, son, and closest friends. In May, she began telling other friends, and in July the administration and faculty at Bard College, where she teaches writing and the history of photography. In September, she made the news Instagram-public, with a photo of herself smiling—grinning, really—and a caption that read, in part, “I have been shilly-shallying about this long enough. Yes, this is me, and yes, I am transitioning–I have joined the other team.”

Sante also eventually added a statement to the front page of her website. “I began my gender transition in mid-February, 2021, when a shaft of light appeared in my subterranean cavern and I was able to see the whole prospect of my life at once,” she wrote. “Gender transition is something I really should have undertaken in my teens, but it was impossible then and for many years thereafter. Now, in my sunset years, I realize that I need to live before I die, so here I am.”

Among her oldest friends, the reaction has been one of gentle but overwhelming joy.

“It was not something I’d ever expected,” said Darryl Pinckney, himself a famed writer and one of Sante’s oldest friends, beginning when they were college roommates in the 1970s. “You have these friends who you want to be happy, at last. And she’s one of them.”

In some ways, Sante has been writing around the subject of her gender for much longer than anyone realized. The subject was buried inside other things: her ruminations about the ways that our public identities are shaped by the world, our family, our origins and accidents of history. Her 1998 memoir, The Factory of Facts, begins not once, but nine different ways, nine different versions of how her life could have played out.

The first is how things actually went: She was born in Verviers, Belgium in 1954, to a deeply Catholic mother, Denise, and a father, Lucien, who worked at an iron foundry that manufactured wool-carding machinery. Sante also had an older, stillborn sister, Marie Luce, whose death her mother never quite recovered from.

“My mother took it exceptionally hard,” Sante said. “I suspect she was already emotionally precarious before that point, but afterward she was never not depressed. And called me by female diminutives all the time when I was a kid. There was a sense that she wanted me to be, or thought I was, this dead sister. “

The family emigrated to the United States not once, but twice. First, they landed in New Jersey after the factory that employed Lucien went bankrupt. They attempted to return to Belgium when the factory reopened, and Sante’s parents, flush with optimism, even bought a house. But one day, Lucien noticed that the factory’s management was once again doing a stock inventory, a “harbinger of doom,” and the family emigrated again to New Jersey, puzzling their way together through the touchpoints of 1950s and ‘60s America: Everything was big, loud, flamboyant, slick, relentlessly, almost pathologically forward-looking and bright.

“America in those days,” Sante wrote in Factory, “was trying to achieve a gleaming, diamond-hard, aerodynamic surface.” It was a marked contrast from the muted world of Belgium, which prized modesty, discretion, and understatement; everyone who knows Sante describes her as holding those qualities all her life.

Sante is barely a character in her own memoir, she acknowledges. “I think of it as a memoir that cuts out the principle subject, which is me. It’s all about the environmental factors but it’s not about me.” Instead, it’s about Belgium itself and what makes up the Belgian character, about memory and ancestry, and, to the extent that it’s personal at all, largely circles around the wonder and mystery that her reserved and modest parents chose to leap, twice, into the unknown of a new country.

Now, Sante said, “I was thinking about my gender when I wrote the book. I was never not thinking about it.” But, she added, “I didn’t know how to think about it. I didn’t know how to apply the knowledge to my life. If I thought about changing my gender, it felt impossible in view of a million things.” (Even now, she wrote in her Vanity Fair piece: “My parents have now been dead for 20 years, but I cannot bear to imagine their reactions.”)

Even if transition had felt personally or culturally possible, her means for imagining what that would materially look like were few. “Although I hoovered up every bit of information about transgender matters that came my way, my resources were limited,” she said. “This is something I’ve talked about with other transgender people my age. We didn’t know shit until the internet came along. You’d go to the library in the late ‘60s or early ‘70s and there was nothing. There were tomes on sexology that would give half a page to transvestism either as a neurotic affliction or a bedroom kink. I didn’t know anything about transsexuals,” except as a dated, lurid stereotype: “They were people who went to foreign countries and had their privates cut off.”

Sante was also, as she frankly acknowledges, ambitious. “I wanted to make a name for myself as a writer. If I’d been transgender anytime in the 20th century, that would have had to have been my career.” And she was, as she saw it, already marginal enough: “I’m a dropout. I got kicked out of high school. My life is checkered in various respects.”

Instead, as Sante achieved incredible success as a writer, she also became physically as well as emotionally uneasy for most of her life.

The writer, musician, and filmmaker Adele Bertei first met Sante when they both worked at Strand Bookstore, which she remembers as “an ancient ship filled with books, and we were the crew.”

Sante “was dazzlingly smart and facile with language,” Bertei said; at the time, Sante was editing Stranded, a zine by and for the store employees.

While the two became good friends, “There was always some kind of mystery hovering around the periphery” of her, Bertei said. “There was something always held back. And we were pretty close. It wasn’t overwhelming, but it was there. It existed.”

The scene they ran in was “sexually fluid,” Bertei said: “Even the straightest guys in the scene, like John Lurie, there was a homoeroticism about these guys, the way they were with each other, the way they’d touch each other and play. It was very obvious. Women were also very sexually fluid.” But still, “It wasn’t easy to come out in those days” as queer, let alone trans. “I grew up with drag queens who were incredibly oppressed. They were thrown out of their homes, not able to work aside from performance. That was in the early ‘70s.”

Bertei was enthralled by Sante’s writing from the start. “There was a playful kid in a candy store element of her writing that I adored,” she said. “The excitement of the words and language and discoveries. It was so apparent on the page. The earlier work, some people would say it’s hard boiled and non-emotional. There’s a bit of a plate glass thing that happens in the earlier work. But I think she was determined not to express any sentimentality.”

For Bertei, it all came clear when Sante told her the news. “When Lucy first came out to me about transitioning, I remembered Factory of Facts. That’s the missing introduction in the book. This was the mystery she lived with for so long.”

Darryl Pinckney agrees that Sante always had an immediately distinctive writing voice. After he and Sante met as college roommates, they continued their friendship through budding writing careers at the New York Review of Books. “There was always a very refined ear,” Pinckney says. “Precise visual sense. Strange connections between things, these leaps of the imagination. And I think of her as someone whose voice was already there. Already formed.”

Sante was also “very reserved, very private,” Pinckney said. “Not easy to know. But once she trusted you, the greatest warmth and loyalty and sensitivity about all things. This is a terrific friend. I cannot tell you. A great capacity and talent for friendship. Really a rare mind and sensibility which was evident from the start, from one’s first conversations with her.”

“This was the mystery she lived with for so long.”

Both Pinckney and Bertei remember the downtown New York scene of the 1970s as both thrilling and, as Pinckney puts it, “exhausting,” with a focus on coolness that often weighed heavily on how men, particularly, felt they could look or behave.

Its weight fell on Sante in a particular way. “I didn’t know how to stand,” she said. “I was eternally self-conscious and ill at ease. And socially, that was always a mystery to me. I know hundreds and hundreds of people but in my worst moods I’ll say, ‘I have no friends.’ The reason I felt that way is that I couldn’t confide in anybody. I was keeping a great part of myself in lockdown even with my oldest, dearest, closest friends.”

And despite her closely observed portraits of New York, trans people are also barely visible in much of Sante’s work. Some of that, particularly in Low Life, has to do with the primary documents she was working with and the fact that she chronicled eras where such a thing was often considered more or less unspeakable; in the book, she even struggled to accurately describe gay or lesbian nightlife, due to the bigotry of her source material. Of The Slide, an “open and undisguised gay bar” on Bleecker Street, she wrote, “It is all but impossible to get an idea of what it was like, unfortunately; the loud distaste of contemporary chroniclers made them incapable of turning in an actual description.” It’s equally impossible not to imagine the modern chronicler, studying her sources and deciding to keep her secret self hidden, safely unobserved for just a little longer.

Not long after Sante’s egg cracked, she began a friendship with Leor Miller, a 24-year-old photographer, writer and musician who’s also a trans woman. At Bard, Miller had been the student of Barbara Ess, a famed photographer known for her arresting pinhole camera portraits, who was a longtime friend of Sante’s. Ess died of cancer in March 2021, and Sante had been moved to hear Miller speak at her Zoom memorial service, and to hear Miller’s thoughts about Ess’ teaching methods. Miller provided a vivid new window into an aspect of her old friend’s life Sante hadn’t known.

“I knew immediately I had to get in touch with this person,” Sante said, both to connect about Ess and for another reason.

In Miller’s recollection, Sante cut to the point: She wrote Miller a message on Instagram saying, simply, that she’d realized she was trans a few months ago, and wanted to ask about Miller’s experiences.

“I can’t say whether I expected it,” Miller says, “I didn’t know her very well. I was unbelievably flattered and honored and kind of terrified. She’s a giant, and it’s a huge thing. But I had absolutely no hesitation at all that I would do it.” They’ve been in nearly constant communication ever since.

Miller has been out, to some extent, since she was 16 years old, and identified with Sante’s sense of reserve, although her experience of Sante’s personality is quite different. “She can be shy and soft-spoken. But I don’t experience her as being reserved.”

Holding oneself apart even from your closest family and friends, Miller said, “That’s a big part of a lot of people’s trans experiences. Before I came out and even before I came out as a trans woman–when I was still identifying as a boy when I was younger and nonbinary in my late teens–I was really reserved. A sensation that I had was this – not even a fear of, but a sense of dread in meeting people, because you were adding to the list of people who knew you a certain way and who you’d have to eventually explain something to. One does play their cards close to their chest when you’re quite literally hiding something. Not consciously, but when there’s something repressed.”

For Sante, the chance to connect with a younger trans woman, to have frank conversations about the politics of passing, was invaluable. Both share a distaste for older narratives about how a trans woman “should” look or act: middle-class, respectable, perfectly made-up. “It was incredibly essentialized and based in a heterosexual understanding of the world and what it means to be a woman,” Miller said. “ We’re not poster children of the perfect [trans woman]- we have qualms with the whole idea of passing. Lucy and I both have voices in a deeper register and don’t have any feelings about changing that. I get flack for it even now. But 50 years ago it would’ve been much worse.”

Being an artist and weirdo herself, Miller was also well-positioned to understand some of Sante’s specific anxieties. “There was a period where she was concerned about coming out publicly,” Miller remembered. “And said, ‘Everyone is going to explain my body of work and say, of course she had a proclivity for the seedy underbelly of the metropole because she had an affinity with it.’” Miller laughed. “Which of course she does, but not because she’s trans.”

The process of transition, Sante said, has been not unlike what she learned when her family first arrived in this country. “The process of learning to be a woman reminds me of the process of learning how to pass myself off as an American,” she said, dryly. “There were distinct similarities.” But this time she had a guide. Miller also helped Sante ease into the practicalities of being seen as a woman in public.

“She took me out into the world,” Sante said. “We did a lot of walking around and going to public places. It was thrilling. She made it very easy. She made it easy for me to transition somehow from overwhelming self-consciousness to really not being self-conscious at all.”

Their friendship, Miller said, has been moving for her too. “It has been an unbelievably beautiful experience.”

Sante is someone who’s thought deeply for years about photography, the complications of seeing and being seen; her book Evidence is a compilation of crime scene photos from 1914-1918, taken from the New York City Police Department’s public archives. She’s taught the history of photography for years at Bard, but being seen was, for her, naturally a complicated matter for years. She did not—for reasons that are, in hindsight, obvious—particularly enjoy being photographed.

That, too, has changed. The day before we spoke, she’d been photographed for Vanity Fair by Ryan McGinley in a marathon four and a half hour session. “It was fun,” she said, with something approaching amazement. “It was completely different,” although, she acknowledged, “I’m still worried about what it’ll look like in the wrong hands.”

Previously, Sante had many rules for how she’d appear in photos, and really, how she appeared at all; particularly, she never smiled with her teeth. “Now that’s all a memory,” she says. “After six months on HRT [hormone replacement therapy], I look most reliably feminine when I’m smiling. I must’ve known that in the past and that’s one of the reasons why I didn’t allow myself to do it.”

“The smiles in the photographs,” Darryl Pinckney said. “That’s new. I find that touching. In past photographs there’s a kind of ‘taking on the camera’ expression.”

Adele Bertei wonders if Sante’s new sociability and ability to connect will translate in her writing. “For me Lucy has always been—her perspective is like a detective at a carnival,” she said. “What she discovers is always delicious, the way she spins it, but I’m interested in seeing how she’ll write going forward. If that lack of sentimentality will transform into more of a warmth for the subject.”

The one area where her life that has seriously changed is in her relationship with her partner, a writer and editor whom Sante had been with for nearly 14 years. (Sante has also been married twice before, and has a son who’s now a young adult.)

COVID was an especially happy time for her and her partner in many ways, Sante said. “My thought now is that what was significant about that period is that maybe for the first time in my life I felt emotionally secure enough to do it, I felt safe.” Her partner was also deeply affirming when she came out—Sante wrote in Vanity Fair that she even gifted Sante a “jazzy 1970s wrap skirt”—but she was also, at that time, not able to be in a romantic relationship with her as a woman.

“The upshot is that when I came out to her she was very encouraging, very moved, and very sweet,” Sante said. “She’s still all those things, but she doesn’t want to be with a woman. And it was one or the other.”

Apart from that particular shift, transition has been both extraordinary and mundane. Many of the things she worried about—the reactions of her friends and, particularly, her son—have proven to be supportive and positive. So too has the process of transition itself, which can be as administrative as anything else: legally changing her name, having her bylines updated across her books and the places where she’s a contributor, retiring an email address bearing her old name. “It’s slowed down nowadays because there’s not much left to do,” Sante said.

Nothing left, that is, but to go on tour: In late fall and early winter, before the country was beaten down yet again by the Omicron surge, Sante did a series of reading dates with two old friends, Bertei and writer Mike DeCapite, another habitue of the same era of the New York downtown scene.

On a mid-November night in Los Angeles, at an event at Skylight Books in Echo Park, Sante read after DeCapite, the room full of their friends and fans. She wore a gauzy, pleated ankle-length black skirt, a cut-off yellow tank top with Arabic lettering across it and the words “Cinema Rif” below that. On her neck, she wore a slender stack of layered necklaces; tattooed on her arm was a simple black sacred heart, with the word Littérature above it. She looked supremely comfortable, although that was not, as she said later, particularly related to her transition: “I’ve always been a ham, love giving readings, been doing so since I was 17. Transition may have made me a bit more of a show-off, since this tour is my coming-out parade as well as just book promotion. But it hasn’t really affected my reading style.”

Sante began with a poem that, as she told the room, she’d written at age 24. “It’s eerily predictive of my life right now,” she said, half-smiling. “I thought I was writing something about movies.”

The poem is called “Easy Touch,” and she read it with a distinct, oratorial, almost ceremonial cadence. It’s an odd, stirring portrait of a strange and spectral figure, and some moments were almost startling in their prescience: “It was the beginning of a new dream which was real life, or the manifestation of an old one at its cusp,” one line reads. Another, which Sante said she finds especially resonant these days: “So strange to be someone lifelike but too early.”

Next, she read two pieces from Maybe People Would Be the Times, her latest book of essays, many of which turn, in unexpected ways, on two of Sante’s longtime preoccupations: music and life in New York City. The second, “The Unknown Soldier,” is a sort of disquieting bookend to the litany of biographies at the beginning of Factory of Facts. It envisions the deaths of a chorus of narrators, all of whom meet their ends in New York, over a landscape of what feels like 100 years. (“I was hustling a customer who looked like a real swell, but when we got upstairs he pulled out a razor,” one passage reads. “I owed a lot of rent and got put out and that night curled up in somebody else’s doorway, and he came home in a bad mood.”)

As she read, people in the room noticeably leaned forward; there was a sense of rapt unease, of watching someone walk a tightrope. She read out the last lines, which also close the book itself: “Take my name from me and make it a verb. Think of me when you run out of money. Remember me when you fall on the sidewalk. Mention me when they ask you what happened. I am everywhere under your feet.” Sante punched through the last word, giving it a deft twist of extra emphasis, and closed the book. There was silence, a collective exhale, and a long round of applause as she modestly stepped aside.

As Bertei read after her, Sante slipped on a cropped velvet jacket and a pair of round black glasses. Soon, she would don a white mask and wade into the crowd to accept a round of hugs and sign some books, then head for dinner down the street with friends, the hem of her skirt trailing after her in the evening chill like a slinky black familiar. But first, privately, with no one really watching—as if she’d been doing it all her life—she smiled.

This piece was updated after publication to more closely paraphrase Sante’s descriptions of her relationship.

More

From VICE

-

Photo: MediaPunch/Shutterstock -

(Photo by AFP via Getty Images) -

Screenshot: Ubisoft -

Screenshot: Bethesda Softworks