A motley assemblage of army veterans, yogis, and psychonauts are mingling in April in the garden of a luxury property just outside Austin, Texas, on the hottest day of the year yet in the state. Some 350 people are here to dance to ambient music and celebrate a unique new religious congregation that worships with a psychedelic sacrament – one they claim to have created themselves by crossbreeding magic mushrooms with hallucinogenic toad venom. Welcome to the Church of Psilomethoxin.

This all came about because co-founder Ian Benouis, a former US army Blackhawk helicopter pilot turned psychedelic medicine facilitator, was searching for the ecstatic afterglow from the powerful drug 5-MeO-DMT without the earth-shattering and ego-destroying trip it usually entails. “It has an incredible release factor for people with trauma, but not everyone is ready for the deep dive,” Benouis says.

Videos by VICE

He and others are on a mission to abate the veterans suicide crisis with psychedelics. They believe that synthetic 5-MeO-DMT – or its natural version in the form of bufo, derived from the venom of the Sonoran toad – could help. As many as 1,000 veterans have already smoked this psychedelic drug, according to Benouis, who is also an advisor for The Mission Within, a psychedelic retreat for veterans suffering from PTSD and other mental health conditions. If he could find a more relaxed microdosing method, Benouis thought he could spread the gospel of bufo even further.

“There’s at least 44 veterans who are killing themselves through suicide a day,” he tells the crowd from the stage of the church’s first public-facing event, a one-day festival dubbed Entheogenesis. “It’s just totally unacceptable.”

What Benouis doesn’t mention is that the church has already caused controversy among psychedelic researchers, mainly down to its mystery sacrament. Just days earlier, a scientific study, which is yet to be peer-reviewed, tested a capsule of the sacrament supplied by an anonymous church member and could not find any traces of psilomethoxin.

It caused an uproar on Twitter, but here in Austin it seems that folks are universally enjoying being under the influence of whatever the medicine does contain. “It’s not even so trippy; my anxiety and fear is gone, and I’m really just more myself,” says Mark Couillard, an Austin artist and musician who is also setting up the church choir.

In early 2021, Benouis was trawling the internet looking for leads on how to create a milder and longer lasting version of bufo. He soon discovered what he describes as a “sacred treasure map”, courtesy of pioneering chemist Alexander Shulgin, the man who first synthesised MDMA in the 70s. In a 2005 interview, Shulgin was asked why his encyclopaedic drugs book TiHKAL had left out a mysterious psychedelic known as psilomethoxin (or 4,5-HO-MeO-DMT, to give its chemical compound).

Shulgin said that the compound would be “fascinating” to explore, but that it remained “virtually unknown”. Experimental chemists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris first synthethised it in 1965 after extracting it from the Mexican vanilla orchid, but it was never preserved.

The crusading psychonaut did, however, leave a rudimentary guide for future seekers of this elusive drug. “I’ll give you even odds that if you put spores of a psilocybe species on cow droppings loaded with 5-MeO-DMT, you would come out with mushrooms containing 4,5-HO-MeO-DMT,” Shulgin said.

This would create “a psychoactive mushroom that contains no illegal drug”, he added, despite being reverse engineered from two controlled substances. Benouis, who worked as a Pfizer sales representative following a four-year army stint that left him with PTSD and traumatic brain injury, promptly asked Mari Thomas – a mycologist friend and professional magic mushroom grower – to give it a try.

Thomas, who is speaking anonymously as psilocybin and 5-MeO-DMT remain illegal in her state, tells VICE that she tweaked Benouis’s recipe slightly, replacing the suggested cow dung with coconut fibre. “There’s a certain step when you grow mushrooms where you add water. We talked about the amount of holy salt [5-MeO] that would be dissolved in the water and I did that,” she recalls. “It’s really easy – it’s a minimal step.”

Once Benouis and his posse sampled her creation and reported that “it totally worked”, Thomas got high on her own supply. “It is a little weird doing this process and not knowing exactly what is happening: I like data and science,” she adds today. “I want to see a lab report. But now I’ve tried them, I know it’s not like psilocybin – it feels very different, even though they look exactly like regular psilocybin mushrooms when they grow. I feel a oneness with the whole world when I take them.”

And lo: A new psychedelic compound was apparently born, and history was made. At the Texas frat house where Benouis and his brethren congregate, and where several Sonoran toads live in a tank, they christened it their sacrament: the love child of magic mushrooms and 5-MeO-DMT.

Crucially, however, they didn’t record any scientific evidence about the hybrid drug, beyond slightly refining their elementary recipe. Instead of commissioning lab tests on animals, or on humans with a control group, Benouis and his inner circle followed in the footsteps of those who first discovered 5-MeO-DMT in the Sonoran toad: They experimented with the substance themselves, eating progressively larger doses of the mushrooms – which they refer to as the “fruiting bodies” – to see what would happen.

“It was the most beautiful experience I have ever had,” says Ryan Begin, a Marine Corps Veteran who has also campaigned for access to cannabis. He was among those who first consumed the drug with Benouis on a five-day retreat at an Airbnb in rural Texas, in which they ate simple food, went hiking and swam in the Colorado River. “It showed me how much ability we have within ourselves to create who we want to be.”

Benouis, in a T-shirt decorated with an illustrated caveman sporting mushrooms for fingers, recalls his first trip with boyish enthusiasm: “As soon as we all did it, we recognised the 5-MeO-DMT profile and could see how helpful it could be to people. We just started sharing it from there.” (Benouis says that he later told Wendy Tucker, step-daughter of the late Shulgin, that he had “pulled a Shulgin”.)

He, Begin and his two other veteran friends Benjamin Moore and Greg Lake, the author of The Law of Entheogenic Churches in the United States, set up the Church of Psilomethoxin shortly after. To defend the open consumption of the drug, they made use of a 2006 Supreme Court ruling that backed the right to access controlled substances as part of religious observance.

“We have a unique gift here and we have to protect it from the government,” Benouis says of the church’s substance-slash-sacrament. The church was certified by the Texas Secretary of State’s office in November 2021 as a nonprofit. On its website, it declares that members further their path of spiritual development through “the circumscribed consumption of our sacramental supplement”.

Extensive experimentation continued, along with tweaks to the laboratory process to make it less visually trippy and more conducive to DMT-style relaxation. Once Benouis and his compadres were satisfied that it was safe to consume, he says they offered microdoses to the public while walking around events like SXSW and invited people to join the church for an annual fee of $55.55.

“It’s like an antidepressant,” says the church’s first member Jose Maldonado, also a combat veteran. “It tones down the chatter in my head and makes me more aware of my body. It helps me just be myself and do simple things.”

The church has more than 1,750 members, internal data shows. Their sacrament is now produced in Michigan, US, and sent to Mexico to be produced into a chocolate, capsules back in Austin and gummies in California. Members, around one in ten of whom are US veterans, pay $300 for a six month supply of daily microdoses, which equates to 28g and would also be enough for about 10 medium strength trips. They live all over: Church records show congregants from across Europe, North America and even further afield in the UAE, Japan, and Australia.

“This is our coming out party for the church to celebrate its existence, that there is this amazing sacrament, and to go on the offensive against the war on drugs and end the mental health crisis,” says Benouis of Entheogenesis, a portmanteau of the words entheogen (a sacred plant which brings about non-ordinary states) and synthesis.

Throughout the day, he and his comrades periodically hand out the church’s sacramental medicine in chocolate and capsule form to enthusiastic recipients. “We’re going to look back at this event and it’s going to be like, ‘Do you remember the first Entheogenesis?’ I was there brother, I was there,” says a topless beneficiary as Benouis surprises him with a 150mg capsule presented in a tinsel package.

Meanwhile, the local sheriff visits and does a walkabout before leaving. “He felt the positive vibrations,” says Moore, a former Army recruiter, while handing out dozens of 250mg chocolates from an enormous bag.

Believers say that the drug is less intense and stimulating than mushrooms, but more ego-softening and heart-opening — like 5-MeO-DMT or bufo — while still feeling profoundly energising. “I usually send 20 to 40 orders out per day,” says Sarah Letcher, who runs the delivery service by herself from Austin. “I wake up excited to do it: It’s like a meditation process for me too, so I can put my calming energy into the packaging.”

The church already holds fortnightly virtual services over Zoom and regular psychedelic integration groups as well as a weekly “hikro-dose” at the nearby Crews Lake wilderness park, where attendees microdose while hiking.

The alcohol-free Entheogenesis event, in which attendees are asked not to take any drugs aside from its sacrament – though there is a ganja yoga class and the pungent aroma of weed is never far away – is intended to serve as a blueprint for future jamborees all across the US. General tickets cost $300, although the church later tells VICE that the event didn’t break even. Still, the church is planning a ceremony facilitator course to help get their sacrament out there ever further.

“It’s like enlightenment: You can see everything more clearly,” says Erica Briody, a former executive at the pharmaceutical company Novartis who has taken four sizable microdoses of the sacrament at the fiesta. “Perception is different: You feel a closeness to people. In a time where people are struggling so much in the world, this is what is needed to help people get through the day.”

She has flown here from Florida, while others drove through the night from northern Oklahoma to hear veterans tell the crowd that the nebulous sacrament could help the fifth of Americans who are on antidepressants. “I think it could change the world,” says Meagan Pilawski, a former oncology and palliative care nurse who is now the community outreach lead at the church. “In 50 years from now, if you ask about psilomethoxin, more often than not people are going to know what you’re talking about.”

The Church of Psilomethoxin had been operating somewhat under the radar, but it was galvanised to go public after the Drug Enforcement Agency in July ditched controversial plans to ban five psychedelic compounds in the face of widespread opposition. Its website proclaims “the kingdom of God is within you” and that “through working with our sacrament, Sunday services, integration, and community service work, the church intends to create a loving community of aligned practitioners”.

However, in the absence of a scientific study to back up anecdotal reports of its sacrament’s benefits, the church has been subject to growing scrutiny. Chemists from the Usona Institute, a US non-profit that does psychedelic research, analysed a sample of the substance handed out to church congregants and published a preprint study three days before Entheogensis. The results were startling: The researchers failed to identify psilomethoxin in the sample. Instead, they found psilocybin and psilocin – more commonly seen in magic mushrooms – both of which remain illegal across most of the world.

“The church’s assertions regarding the production of psilomethoxin in mushrooms appear to be unsubstantiated,” its authors write. “These data lead us to consider the likely possibility that the reported unique effects could be attributed to the placebo effect.”

“The lack of evidence of novel compounds in the sample coupled with the implausibility of the proposed biosynthetic pathway suggests that the Church of Psilomethoxin is engaging in misleading marketing practices and may be misrepresenting the material that they are distributing.”

In response, the church hit back the next day against what it sees as corporate interests coming after a DIY congregation. (Usona was co-founded by the CEO of biochemical corporation Promega and is headquartered within its premises.)

One of the preprint researchers also co-conducted a 2021 study in which another novel tryptamine was created from psilocybin, which the church alleges raises questions over their intentions: “They don’t want other people disrupting their business model,” Benouis told VICE. When asked for comment, lead chemist Alex Sherwood said: “Our preprint paper addresses many of your questions.”

But mystifyingly – after prior suggestions to the contrary, including anointing their church as the Church of Psilomethoxin – the co-founders have gone on to contend they never said psilomethoxin had been scientifically identified in their sacrament, and that it is inevitable psilocybin would still be present to some degree.

In a post on its website published on 14th December 2022, the church had already admitted that it had been unable to detect psilomethoxin in its sacrament through GC-MS analysis, most commonly used to identify chemical substances. In the April statement drafted by Lake, who is listed as the church’s lead oracle, it goes on to claim that psilomethoxin may be “a poor candidate for testing through this process” as it does not vaporise easily enough. The church also claims that there is “strong evidence to suggest that an inauthentic or adulterated sample was tested” in the preprint study.

At Entheogensis, Benouis nonchalantly waves away the doubts and floats another possibility. “I am willing to accept that until fully scientifically tested, it could be an unknown tryptamine,” he says. The sacrament, in other words, could be a hallucinogen that is very similar to psilomethoxin but has not yet been identified by science.

In lieu of provables, the Church of Psilomethoxin is asking people to trust its sacrament through good old-fashioned religious belief. “Our claims to the existence of psilomethoxin, at this time, are solely based on faith, bolstered by our and our members’ own direct experiences with the sacrament,” reads its now-deleted public statement, which has been archived here. Its website continues to claim that “our spiritual sacrament, psilomethoxin, is contained within mushroom fruiting bodies.”

This gung-ho response to the provocative paper ruffled feathers in the scientific community, and further criticism quickly followed. Psychedelic chemist David Nichols has dismissed the idea that psilomethoxin could not be identified. “The church has a completely nonsensical and nonscientific position,” he told nonprofit media organisation Psymposia. “The [Usona] paper uses proper analytical methodology to show that there is nothing in their ‘psilomethoxin’ sample with the properties of the claimed compound.”

The church has been lambasted by Psymposia and others, including neuroscience PhD student Zeus Tipado and chemical pharmacologist Andrew Gallimore, for its response to the Usona preprint. “The statement, riddled with errors and self-contradictory claims,” Psymposia managing editor David Nickles writes, “offers a case study in psychedelic charlatanism.”

Rayyan Zafar, a neuropsychopharmacologist at the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, warns that some novel tryptamines which share similar biomolecular structures to psilomethoxin have even been found “to cause lesions in animal brains in experimental sessions and have been shown to irreversibly damage serotonergic neurons,” he tells VICE. “So a key part of developing novel compounds is to put them through safety testing before human ingestion.”

Manesh Girn, chief research officer at psychedelic-assisted treatment company EntheoTech Bioscience and a neuroscience PhD student, tells VICE that the church — through its “highly defensive and ad hominem statement” — seems to be “denying the research while simultaneously saying it doesn’t matter anyway because it’s faith, and facts are irrelevant.”

However, he acknowledges the anecdotal reports of the distinct effects of the sacrament: “Maybe there’s something in there, whether it’s a novel tryptamine or something else synergising with the psilocybin to activate it”. But, he cautions, “we can’t be too certain.”

For Girn, the self-styled Psychedelic Scientist, it comes down to the intentions of the church leaders. “Why are they doing this: Do they believe in the power of the sacrament and are they sharing it from their hearts? Or is there some ulterior motive? Given that the sacrament is sold relatively cheaply, there is unlikely to be a financial incentive. But why this hostile defensiveness?”

Devotees naturally jumped to its defence upon the publication of the paper. A member of the church posted on Twitter attesting to the distinct effect of their hazy sacrament after three months of usage: “The church stuff acts very differently [to psilocybin]. No tolerance forming. I rely on my experience, not faith, to believe this is something else, and valuable.” The church has now hired an analytical scientist, Adam McKay, as its “director of sacred synthesis” to undertake confirmation testing.

It maintains that anyone who has sampled their sacrament would know that invoking the idea of a placebo effect, or suggesting the experience is basically akin to magic mushrooms, is nonsense. Unlike psilocybin, it notes, there have been little to no reports from followers of nausea or changes in heart rate. The co-founders also claim that there have been no reported adverse reactions to their drug after thousands of trips, though few devotees have taken extremely large doses.

Naturally, the preprint study is a hot topic at Entheogenesis. “The sacrament is far different from any psychotropic or psychedelic feeling that you could ever have,” says Leland Holgate, a combat veteran and breathwork facilitator. “There’s still some visuals that might happen, but it’s just relaxation and peace that comes over my entire being: absolutely amazing.”

There are no plans to stop sharing the sacrament, even if some believe acolytes are simply drinking the Kool-Aid. And it comes as a kaleidoscopic wave of psychedelia continues to engulf the US after Oregon and Colorado legalised guided psilocybin trips. There are now hundreds of similar churches across the country, many of which have formed over the past five years.

Texas – the first state to fund a psychedelic study and the freedom-loving, anti-big government land of the free (so long as you’re white, obviously) – is perhaps the best place in the US to start a psychedelic church, thanks to the extra religious protections enshrined in its laws.

“There’s a rich story to tell and infer about Austin’s underground psychedelic culture,” Jamie Wheal, author of Recapture the Rapture: Rethinking God, Sex, and Death in a World That’s Lost Its Mind told Lucid News. “Way back to the 70s, it had this cross pollination of country and hippie culture and it was always the southernmost stop on the psychedelic circuit. At the same time, it always had a specific Texas flavour of effectively cognitive libertarianism: like, ‘What goes on inside a man’s head is his own business’.”

Benouis and Lake, who are also both lawyers, have helped dozens of “medicine churches” establish their legal and religious right to use bufo and other psychedelics. Benouis told Lucid previously: “The churches are the only way to get the medicines out to people who need them in a timely way. They’re a way to fight the drug war and take back our rights.”

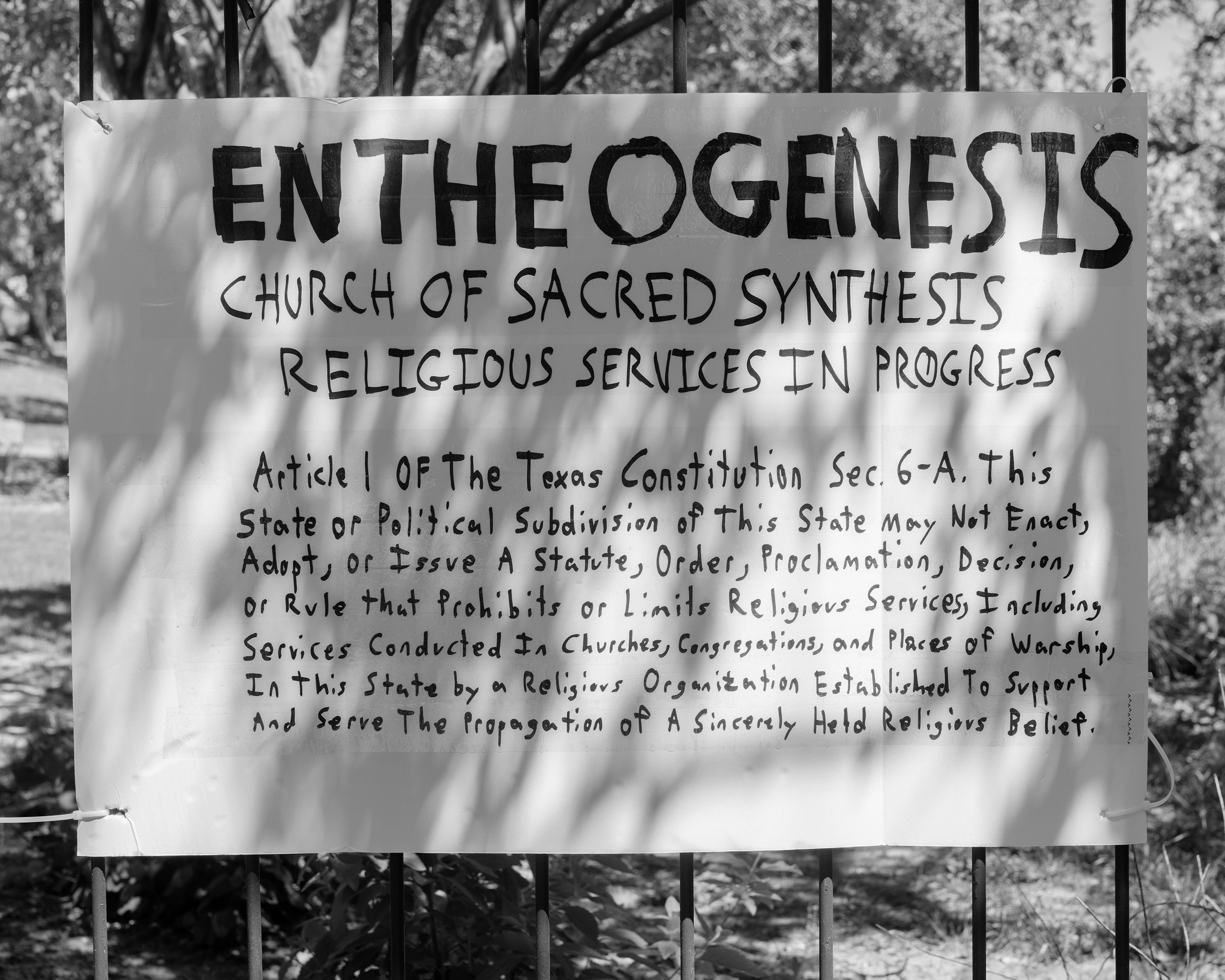

At Entheogenesis, attendees to the event pass a sign at the entrance which states that a church service is in progress and cites the state constitution in defence of their activities. “This state… may not enact, adapt, or issue a statute, order, proclamation, decision of rule that prohibits or limits religious services, including services conducted in churches, congregations, and places of worship in this state by a religious organisation established to support and serve the propagation of a sincerely held religious belief.”

It may be difficult for some to believe that people at Entheogenesis are practising a religion, let alone worshipping God. But Rak Razam, co-founder of the World Bufo Alvarius Conference and author of In A Perfect World, says the legal use of psychedelic plant medicines is central to many Indigenous faiths and that the Native American Church, along with the Santo Diame and Uniao de Vegetal religions, successfully fought in the US to establish the legal right to connect with the divine through psychedelics. (The congregation of the Church of Psilomethoxin, in comparison, is mostly comprised of white Americans – like many psychedelic communities.)

“The Church of Psilomethoxin is the latest in a long line of structures which exist to facilitate divine experiences,” Razam says. “It gives people a platform to meet, to gather, to discover, to renew, and to grow. Healing comes from connection and spiritual community.”

Benouis, a well-upholstered, 58-year-old grandfather-like figure who is a midlife convert to Islam, says that his church’s psychedelic – whatever it may actually contain – ultimately provides him with a portal in which to connect with his spirituality. “I took it and it made it easier for me to say yes to God. This is a divine gift from source and is my holy sacrament.”

Benouis still prays five times a day, but stopped going to the mosque he attended for more than 20 years after getting divorced and moving homes. Now he leads the church’s trippy hikes: “I’m down with leveraging nature as the temple – it cuts off the middle man,” he says.

As night falls at Entheogenesis, the DJ thanks the Church of Psilomethoxin between bassy, vaguely Eastern-inspired tracks as the energy of an outdoor rave reaches fever pitch. Some 50 people jive and wiggle like snakes practising Tai Chi — channelling the loosening energy of the sacrament. Benouis sways at the back of the tent, sporting a satisfied expression as he smokes from a ceremonial hash pipe.

“Everyone else is like ‘Hey, in 2025 you might be able to get psilocybin on prescription’,” the former pharmaceutical rep says. “We can do our own community healthcare now, which is clearly what we must have done in the past.”

Whether the Church of Psilomethoxin is set to become the Pfizer or Lilly of tomorrow remains to be seen. A few weeks later, with no sign of the furore over the contents of their puzzling sacrament blowing over, it rebrands itself as the Church of Sacred Synthesis. But, just in case, it also trademarked psilomethoxin last year.

Correction: This story originally said Ryan Begin was a US Army veteran and that Ian Benouis is general counsel for The Mission Within. Begin is a Marine Corps veteran and Benouis is now an advisor. We regret the error.