Over the past year, the stock market has been on a wild ride that seems to have taken us all with it as “meme stocks” soar and institutional Wall Street investors flame out. Over at Nasdaq, chief economist Phil Mackintosh has been working on a series of posts fleshing out a rosy guide of how markets work for summer interns that is actually pretty revealing. A good chunk of it is the standard fanfare about how we are definitely not in a bubble, how stock markets provide “efficient capital,” how markets have “evolved” into a harmonious system for IPO and trading markets, and so on, but threaded throughout is the distinct sense that things are not so normal.

Last year was a “multi-decade record for IPOs” with 470 public offerings raising $155 billion, Mackintosh writes, even though “many are still unprofitable” or that despite “the volatility created by Covid-19 news” there was an average return of just 38 percent. SPACs, Mackintosh explains, are not so much a consequence of an intensification of speculation or a path to public markets for companies that shouldn’t go public but a result of Covid “making it harder to do ‘roadshows,’ where management visit potential investors before they place stock with them.”

Videos by VICE

One interesting section looks at who actually invests—institutional and retail investors—and what motivates or restricts their trading. Institutional investors, for example, include mutual funds which, Mackintosh writes, limit themselves to public markets because of “listing standards” and since “SEC rules require corporate accountability via quarterly accounting statements and other disclosures.” Retail investors are basically households, individuals who decide they’ll put their money on the market.

Mackintosh tells interns that while retail investors traded more during the pandemic because of “commission-free trading and increased saving caused by stimulus checks and the inability to spend on services” during lockdowns, this may have resulted in meme stocks like GameStop and AMC but it was an illusory and temporary development.

“It’s important to remember though that meme stock trading is not being done by all retail investors. Data shows retail investors mostly trade infrequently and for very small values,” Mackintosh writes. In a graph mapping out trade sizes by dollar amounts and the percent of “price-improved trades”, large trades worth over $50,000 took up less than 5 percent of the trade volume. Close to 80 percent were between 0 and $5,000.

Indeed, Motherboard has reported previously on the retail investor phenomenon, and how institutional Wall Street funds were in the mix and reaping profits on stocks such as GameStop as well.

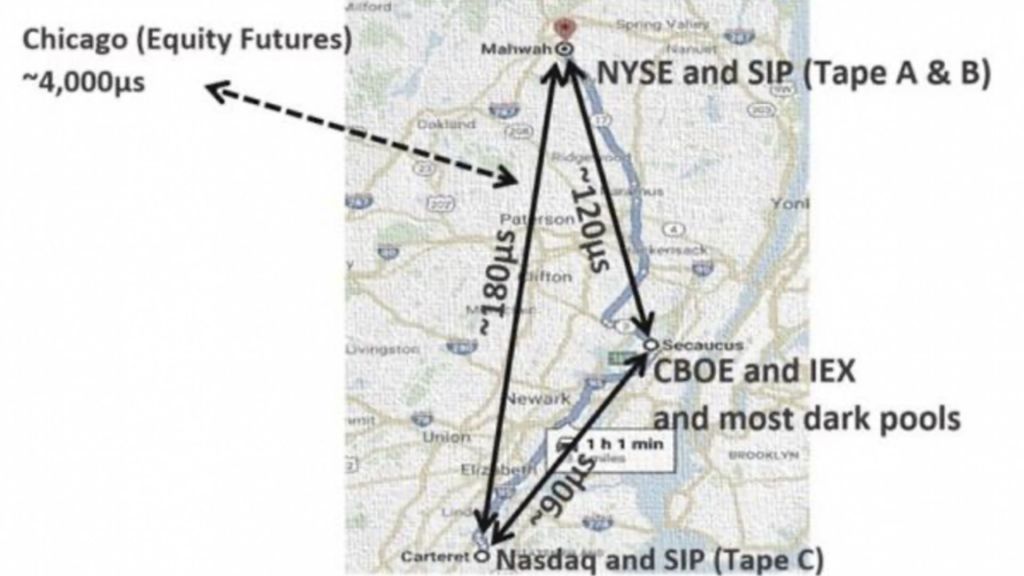

Mackintosh also highlights how high frequency trading has come to dominate the stock market, painting a picture of humans doing very little actual work and computers moving faster than regulators. According to Mackintosh, “the reality is that computers (trading algorithms and market maker models) do most of the trading these days and they can be optimized with data and programmed to fix much of the complexity that human traders face.” Indeed, “The biggest input required from investors is to tell the algorithm how fast they need to trade.”

This allows computers to engage in arbitrage very quickly, where brief differences in prices between markets allow a stock to be bought low and sold high nearly simultaneously. According to Mackintosh, “”real investors’ actually make up just a fraction of overall trading in the market,” with the majority of activity being very fast arbitrage, as well as futures and market making.

While Mackintosh says that all this has made the market faster, more efficient, and cheaper, he also admits: “Arbitrage happens so quickly that the SEC has been spending a lot of the last few years trying to work out how to update regulations to fit the new, faster speeds.”

“But,” he concludes, “that’s a topic for later.”