This article originally appeared on VICE en Español.

West Side Story premiered in Spain on December 7th, 1962 at Barcelona’s famed Cine Aribau. American director Robert Wise’s film was full of colour, joie de vivre and youthful exuberance – pretty much everything that was missing from day-to-day life under the watchful eye of Francisco Franco, one of the 20th century’s great dictators.

Videos by VICE

Franco had been in power since 1939 and would remain there until his death in 1975. Rocked by the Civil War which marked, and continues to mark, all of Spanish society, life under his rule was defined by strict adherence to authoritarianism, conservatism and Catholicism. By and large, Spanish life in the early 1960s was dour, drab, and for the country’s youth population, dull.

Inspired by Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story offered Spanish audiences a musical account of teenage life in 50s New York City, all quiffs, shiny knives, and extended dance sequences. America was just a few thousand miles away from Spain, but to the young audiences who packed out cinemas up and down the country, it might as well have been in a different galaxy.

The film, which features songs composed by the legendary Leonard Bernstein and written by the great Stephen Sondheim, arrived in Madrid a few months later. The youth of Madrid were as captivated by the movie as their Catalan counterparts. Tickets sold out showing after showing and audiences were caught up in a frenzy that made them get up in the middle of the screening, shouting and dancing in the aisles and on top of the seats.

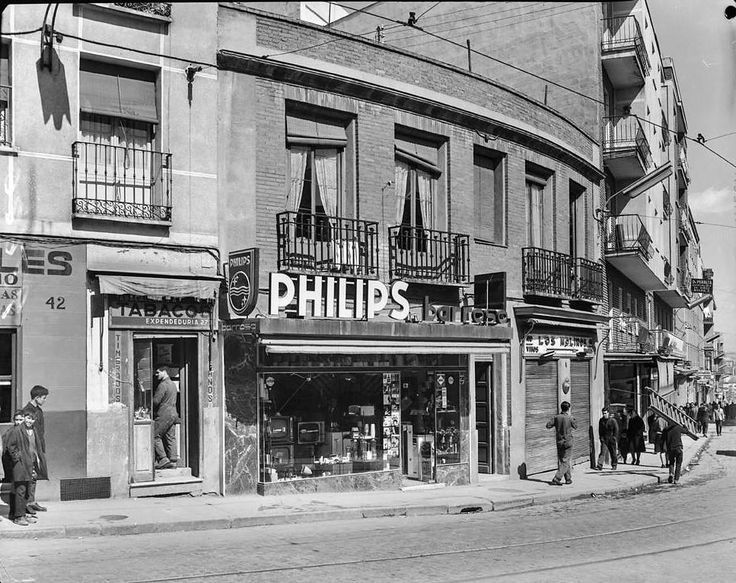

The young people who were so moved by the musical lived in the newly built, peripheral neighbourhoods of the Spanish capital, which were erected at the end of the 1950s under the auspices of Franco’s National Institute of Housing. These suburbs included Usera, La Elipa, and San Blas and they formed part of the Francoist regime’s post-war slum clearance plans.

They were marginalised areas, built in a hurry with cheap materials. They often lacked schools, doctor’s offices, and other essential services. They were largely populated by poor families who migrated from the south, fleeing the misery of Spain’s devastated rural regions.

One of the few distractions available was the cinema. These theatres tended to show films a few months after their original release, which meant that pictures like West Side Story found themselves having extended runs, finding new audiences on a regular basis. Although the streets of these forgotten districts had very little in common with the stylised avenues of New York, the young people who inhabited them emphathised with the problems and frustrations of the film’s protagonists.

This process of identification was so strong, in fact, that something strange happened in Madrid in the early 1960s. Teenagers, presumably unhappy with both their material conditions and the ruling ideology of the day, found themselves forming gangs in the wake of West Side Story’s arrival on the Iberian peninsula. The film maybe wasn’t the cause, but it was definitely a factor.

It is this strange moment which forms the basis of Spanish author and historian Servando Rocha’s latest book, Todo el odio que tenía adentro (“All the hate I had inside”). For six years, Rocha carried out interviews and delved into the archives to try and work out exactly why West Side Story had the impact that it did.

The result is an exploration of a slice of cultural history that was largely unknown to the general public. The post-war years were a fertile time for youth culture, and just like the Teddy Boys in England, the blousons noirs in France, and the halbstarken in Germany, Spain had its own groups of pissed-off teenagers who tried to live life by their own rules in the face of repression from the state.

Madrid’s gangs were comprised mainly of children of poor families who migrated from the regions of Andalusia in the south and Extremadura in the west. Most of them weren’t on the prowl for danger. They just spent their time in nightclubs, bars, and pool halls across the city – groups of teenagers looking to dance, flirt, and enjoy life as much as they could under fascism.

They called themselves things like Los Yes, Los Gatos Negros (“The Black Cats”), Los Pepsi Colas, Los Deans and Los Vikingos (“The Vikings”). The list of names cited in the book is almost never-ending. Each one of these groups controlled a specific area of the city, sometimes only a street or even a bar. This keen sense of maintaining territorial control led to the odd fistfight at weekends.

According to Servando Rocha’s book, the most feared of these gangs were Los Ojos Negros (“The Black Eyes”), a 40-strong squad. They wore their hair long, and stalked in the city in thick leather jackets, and black boots. Members were armed with motorbike chains, switchblades, and knives and razors hidden in the seams of their clothes – weapons they didn’t hesitate to use if things got ugly.

The group took on an almost mythological status for Madrid’s youth. It was a status not necessarily shared by the city’s police force.

Rocha cites an article by writer Moncho Alpuente, who wrote about the Madrid gang in the national newspaper El País in 2007. Alpuente describes them as a “mysterious suburban gang”, noting that while they might have captured the imagination of schoolboys, “any police report from the period would have concluded that there were no organised gangs in the capital, and their conclusion would have been reasonable; what existed were small posses”.

The leader of Los Ojos Negros was a man named Ángel Luis. In addition to his gang duties, Luis occasionally participated as an extra in the so-called Spaghetti Westerns that were regularly filmed in Spain’s southern desserts.

Any leader worth his salt has a second in command, and for Luis it was a man by the name of José Luis Pacheco. A decade after his gangland days, Pacheco would go on to become one of the most famous Spanish boxers of the 70s, even breaking into the top ten welterweight fighters in the world at some point. Like Luis, he also dabbled in acting.

Going above and beyond the occasional Saturday night scuffle outside a bar, Los Ojos Negros regularly carried out robberies everywhere from pool halls to pharmacies. They were even the pioneers of a type of theft that became commonplace in the the 1960s and 1970s in Spain – the tirones (“jerks”). Gang members would speed past bystanders on their motorbikes, snatching bags and any other immediately noticeable objects of value. The technique worked well, and the shock of the new saw the gang able to afford a lifestyle that had previously seemed completely out of reach.

They scared the owners of clubs and concert halls in the city to the extent that they even found themselves employed as bouncers, of a kind. The gang’s grip on Madrid lasted three years. During that time, the police had kept a close eye on Luis and his men, waiting for a slip-up big enough to bring down the full weight of the law.

In 1966, both Luis and Pacheco were arrested and sentenced to three years in prison. The latter was just 16 when he found himself behind bars. Before the duo were imprisoned, they found themselves face to face with one of the most feared members of the police force during Franco’s reign – Antonio González Pacheco, whom everyone called Billy el Niño (“Billy the Kid”). After torturing them for days, he made them confess to dozens of offences and thefts. (The policeman was charged with 13 counts of torture in 2013, but never stood trial and died in May 2020.)

With its ringleader and one of its most prominent members behind bars, Los Ojos Negros started to dissolve. The revolution sparked by a Hollywood musical was over. Spain relaxed after Franco’s death; democracy was slowly restored, and with it came the next revolution in Spanish youth culture: La Movida Madrileña.

Inspired by the punk rock scene which had taken the UK by storm in the late 70s, Madrid’s young people found freedom through artistic expression. It was a moment of release and relief, a hedonistic reaction to the dark and dingy days of life under Franco.

Having spent decades working under the restrictions of strictly-enforced censorship and cultural repression, writers, filmmakers, musicians, visual artists and other creatives were free to fully express themselves. The likes of director Pedro Almodovar and photographer Ouka Leele, key players in the scene, are still making waves today.

In many ways, the violence displayed by gangs like Los Ojos Negros was a reaction to a time and a place. In the 60s, Madrid’s youth felt hemmed-in and cast adrift. Twenty years and a dictatorship later, they embraced another kind of revolution, this one slightly more peaceful.