GARAGE is a print and digital universe spanning the worlds of art, fashion, design, and culture. Our launch on VICE.com is coming soon , but until then, we’re publishing original stories, essays, videos, and more to give you a taste of what’s to come.

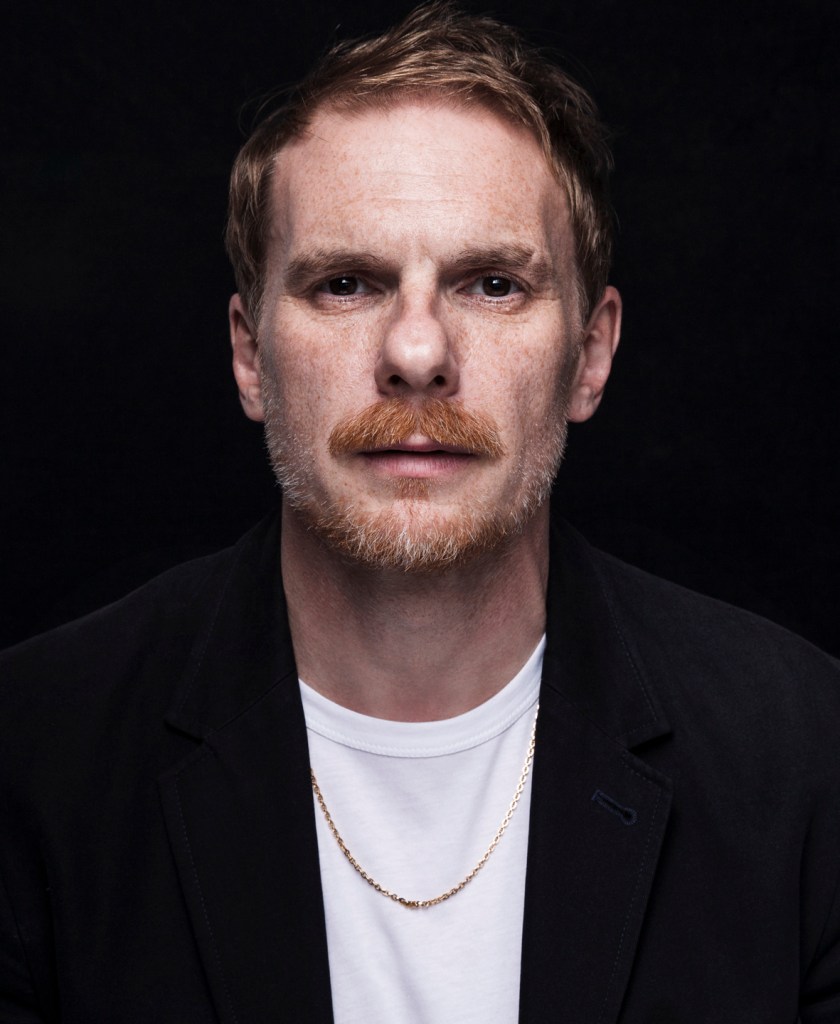

When was the last time you went to a museum to see something that didn’t sit still? Performance is a transformational medium in the history of modern and contemporary art, but institutions haven’t always recognized it with the same seriousness as painting and sculpture. Mark Beasley—former Birmingham Grebo rocker, veteran of New York’s Performa, and now Curator of Media and Performance at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.—is fighting to change all that. In the second of GARAGE’s chats with innovative young curators, Evan Moffitt spoke to Beasley about his life in music and curating, and his plans for the US capital’s most important contemporary museum.

Videos by VICE

GARAGE: You’re a musician. Did you get involved in the art world through your experience as a performer, or vice versa?

Mark Beasley: As a kid, I lived in Stourbridge, a small town outside the industrial city of Birmingham, England, which while not so strong in the visual arts has a significant musical pedigree across various forms: metal with bands like Black Sabbath and Judas Priest; two-tone with The Beat; reggae with Steel Pulse; pre- and postpunk with the Swell Maps, The Killjoys, and GBH; and, lest I forget, New Romantic with Duran Duran. It’s a broad church that has latterly expanded even further to take in hard electronica and bands like Broadcast, who I worked with in my first gallery job. From an early age I was around and involved with bands, some of which later went on to sign record deals, make TV appearances, and tour internationally. In the space of five years in my teens I’d experimented with every kind of sound, look, and haircut! Some of my friends developed sounds that went on to become subgenres, like grindcore or crust-punk. In Stourbridge we were termed Grebo Rockers by the national music press; the sound and look mixed everything from metal through punk to dub—a kind of pre-Seattle sound that already understood humor and the retreading of rock-‘n’-roll antics along with the more fluid and open promises of postpunk. When Grunge appeared, it was a retread of “punk” authenticity, and it killed that scene.

It was the early experience of going to gigs and performing that helped me understand the subculture of music as a creative community. And then, of course, reading liner notes and trying to figure out who designed the front cover of your favourite album, or hearing about friends’ bands who were working with different artists or designers, gave me an awareness of visual art. This led to art school. There was an art college in Stourbridge that I went to when I was seventeen—Peter Doig had his first teaching job there—that had a music venue, and many bands would pass through. The history and legacy of free art schools in Britain from the 1960s through the ’80s spawned a special culture that exists to this day. I ended studying fine art at Bath College, which introduced me to the tenets of Conceptualism, something that which seemed just as strange and as engaging as the music I was listening to. Then one wet Wednesday afternoon I switched to performance studies after seeing a Laurie Anderson video, O Superman, the key work in an exhibition I’ve organized at Kunsthall Bergen that opens this Fall. There was something about performance, the ritual space of the gig, and the crossover between art and music that appealed to me.

Sometime after college I moved back to Birmingham and helped start a gallery, B16. I also continued making my own work, and started working at the IKON Gallery, which is like Birmingham’s kunsthalle. I felt like curating was a field in which I could sustain a conversation with art for a longer period. Later I moved to London, studied curating at the Royal College of Art, and went on to work at the ICA with Matthew Higgs. I also made and exhibited work with my brother, architect Steven Beasley, and showed at the East End gallery MOT. Many years and curatorial jobs later I moved to New York and worked as a curator at Performa. Retrospectively there’s a shape to all this; Performa has a very art-school quality in that it’s collaborative and open to new ideas. Performance is this very permissive, promiscuous space, a space in which I would encounter things I didn’t understand but felt I wanted to. That’s a feeling I’ve learned to trust over time.

Public infrastructure and funding for the arts today is much more developed in England than in the United States. Was there significant support for performance and new media at that time? Or was it sidelined?

There was support in London. I moved there in 1998, and I remember seeing Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore in Scott King’s “Crash” exhibition at the ICA in ’99. Something about that film flicked a switch for me. I realized I could talk about musical subcultures and it wouldn’t be dead on arrival in a gallery. I started working at Bookworks in London, who were rethinking artist’s publications, and in 2004, I published a book with Mark Titchner (Why and Why Not) and staged several events under the “Infrathin Projects” banner. There’s a place called Conway Hall, which has a long socialist history—it’s where George Orwell first read publicly from 1984—and I invited artists to present slide lectures there. Again, I was thinking about my first engagement with art history—or a “stop-motion” version of that history as conveyed in a darkened room with a projector and a voice—and thought it might make an interesting forum for the lecture-as-performance. I invited Mark Titchner, Bonnie Camplin, and Mark Leckey; it was Leckey’s first lecture-performance. Performance had been ‘out’ for so long that it was a format that could really be messed with, in ways that art-world audiences didn’t necessarily understand then. That subcultural sensibility really reinvigorated it. Now it feels commonplace; every artist I’ve met from the UK in the past decade has a libretto or a text or a spoken word performance ready to go. No bad thing!

One of my favourite British comedians, Stewart Lee, described how he got his start in stand-up, in the 1980s, when comedians were the intermezzo acts between the sets of different bands. They would wind the audience up while they were waiting for the next band to come on, a kind of variety-show format. There’s something I really like about that populist form, and I’ve been thinking about it lately because a lot of what I do also tries to weave seemingly disparate things together: Laurie Anderson on the one hand, but D.C. hardcore and Minor Threat on the other. They share more than they don’t.

Do you think that aspect of performance is one reason why it’s finally getting its institutional due? It was always recognized, but not with the same seriousness as painting or sculpture. Is this ability to engage with live audiences key to its rise, especially in the age of Instagram and Snapchat?

I think it’s an accumulation of effects; there’s no one cause. With the advent of the digital, there’s a yearning to be in a room with other bodies, and to hear the source speak unmediated. I got to work with the late Malcolm McLaren, and we talked about this a lot. He’d been signed by an agent who was putting him out in front of two thousand people with a microphone, and he would just go at it. He couldn’t believe that anyone would show up for these events, but they did. If you look at the market for these experiences, I think there is some real desire, intergenerationally, for content that isn’t mediated by a screen. To hear with one’s own ears, to see with one’s own eyes! A long time has passed between Futurism and now, from the birth of modern forms of performance to our present iterations, but I think that eventually performance will be accepted the same way photography has been, as an integral but fluid component of the institution. More and more, we see performances happening in many different kinds of spaces within galleries and museums—not only social or theatrical settings—such that the primary challenge for their presenting institutions has become simply dealing with the flow of people.

“The Message,” your upcoming inaugural show at the Hirshhorn, is all about miscommunication. Each work in the show employs “writing, lyric and text . . . rewiring popular modes of address, from the public lecture and concert to the music video and online sex chat room.” How did the idea develop?

First and foremost, it’s an exhibition of new acquisitions; the Hirshhorn has been collecting film and video since 2005. My background is in music, so there’s a common thread through the five installations in the show, which is music or audio. That said, my primary interest was in what each of the artists was saying about faith or belief systems, about our attempts to get at a deeper truth amidst all the visual noise and micro-contact of the digital now. Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2015), for example, follows her attempt to find, by searching the Smithsonian archive, an ‘ur-beginning,’ the beginning of the universe, by considering multiple forms of belief, from American Indian culture through to the Black Panther movement. She finds similarities, an endless wash of creative beginnings, that brings on literal fatigue. It’s presented as if on a computer desktop, with windows popping up all the time in a seemingly infinite stream of footage, and with a poetic voiceover that references Gil Scott-Heron and the Last Poets. The title of the exhibition, “The Message,” was taken from another work in the show, Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), which I saw for the first time at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York. It was the last work that hit me on a deep emotional level. A compelling history of the ‘African American Century,’ set to Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam, it takes the pop form of a seven-minute music video, an aggressively edited sequence using footage from various sources. It seems to get to the root of African American experience in America without being a sixty-minute documentary. So all the works have music, from opera to Motown to rap.

Music videos are becoming longer and more artful these days, while artists like Jafa seem to use the form for political purposes. Do you see radical potential in this?

It’s definitely a populist form, and there have been attempts to use music videos and other formats like it to bypass the market and reach out directly to some idea of “the public”; I’m thinking of the forms and means of reaching out that Seth Price discusses in his key text “Dispersion.” What originally struck me about Fiorucci was that it’s the kind of documentary you’d never see on the BBC. Now we have desktop publishing, and everyone is a “prosumer”—you can buy equipment to make something that “feels” right. It’s the mode of now, though I don’t know what it all adds up to. It’s very clear when a work ‘works,’ and Jafa’s video works. Since Fiorucci I must’ve seen fifty attempts to use that same cut-up format to tell the history of rock-‘n- roll, or the history of black culture, but none stay in my mind so clearly.

A certain amount of bias comes out in the edit, but Jafa employs it in a way that’s neither evasive nor preachy. His intentions are clear, but all we’re dealing with is raw material, footage we may have already seen set to a song we may have already heard. That kind of politics is most effective, because it can really get under your skin.

Jafa talks of his desire to make film that has the strength and quality of black music, and it hits with the energy and legacy of protest and survival against the odds. It creates something curious, engaging, heartfelt. Arthur studied in D.C., so he has a connection to that city, and some of the footage was shot there. Equally, Kanye’s fusion of R & B and gospel has a deep connection to the history of black culture and politics.

The Hirshhorn is uniquely located in the heart of Washington, D.C., right on the National Mall. It’s in the riflescope of the public eye. How does that public factor into your decisions now, as opposed to curating more diffuse projects for Performa or Creative Time, here in New York?

It’s very different. The audience at the Hirshhorn is made up primarily of tourists to the National Mall; many thousands of people pass through there in any given week. So it’s not the self-selecting crowd that will show up for Performa commissions, one that’s aware of particular histories. I like the Jafa work because while the format of the pop video is understood by a broad audience, the work retains real critical content. Works like that share a sensibility that makes them well suited for Hirshhorn. I’ve been thinking a lot about how to introduce difficult ideas in performance and video to a broad public. We organized a series with Theaster Gates recently in which he worked with local music communities and dancers to connect with the history and culture of D.C. And our current Yoko Ono show has been particularly successful; in spite of the austere minimalism of Ono’s work, it’s also deeply human, beautiful, and accessible. For her Wish Tree (2007), a Japanese dogwood tree planted in our sculpture garden, visitors are invited to write wishes and hang them from the branches. After the election, people did hang up political wishes, but the invitation was totally open, so there’s been a diversity of responses. In her work, Ono generously extends the creative hand to her audience, without overt judgement we are open to respond.

You’ve moved to D.C. at an auspicious time. In the 1990s, the Hirshhorn was one of several public institutions that came under the scrutiny of a Republican-controlled Congress conducting what was dubbed the Culture War. Is there a concern that you or others at the museum may face censorship? Can this be preempted?

The Hirshhorn is in a very prominent position so self-censorship would be a concern, but there hasn’t been any. I’m interested to see what the broad response will be to Jafa, but the response from the institution has been that this is an important work by an important artist.

What originally drew me to Washington as a kid was its musical history, particularly that of D.C. hardcore, which is a politically abrasive genre, but also a diffuse one. There are many bands that figure under that heading, specifically the D.C. label Dischord Records, that use music as a platform for many different narratives. Many figures from that scene still live in the city, and it offers a kind of map to understand the way politics figures on a local level. One of my aims is to connect these different audiences and ideas in the way that only performance can.

Mark Beasley is a curator of media and performance art at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., a member of the band Big Legs, and curator of “O Superman to Girls, Tricky. I Am Here, Where Are You: On Vocal Performance” at Bergen Kunsthall (August 25–October 15, 2017).

Evan Moffitt is a writer and critic based in New York. He is assistant editor of frieze.