Twenty five years ago, on April 28, a man walked into the Port Arthur Historic Gaol’s cafe, The Broad Arrow, and sat down for a meal. When he was finished eating he reached into his bag, pulled out a Colt AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, and began a horrific killing spree in which he murdered 33 people, including two children, and wounded 25 others.

Earlier that day, he had brutally murdered Noellene “Sally” and David Martin, a couple who owned a nearby holiday rental accommodation. The massacre totalled out at 35 people. It was, at the time, the worst-recorded massacre by a single person shooter in the world. Today, it remains the worst-recorded massacre by a single person shooter in Australia.

Videos by VICE

Bryant is currently serving 35 life sentences in Risdon Prison. He will die within those concrete walls.

I, like many other Tasmanians, would like the killer’s name to die when he does. But there’s no point shying away from the name of the man who murdered 35 people on a sunny April afternoon. His name is Martin Bryant.

In the years following the Port Arthur Massacre, the rumour at my school was that Bryant was planning on either going on his killing spree at New Town High, Sacred Heart College, or Port Arthur Historic Gaol. New Town High because that was his former school, and Sacred Heart because that was the school closest to him. I know about that rumour because Sacred Heart was the school I attended from 1997 to 2008.

I grew up in the same town as him, just a five-minute walk away from his house, and lived my life in the wake of his slaughter. Martin Bryant repulses and disgusts me. Everyone who was alive and able to form memories at the time of the massacre remembers that dark day.

And, like all Tasmanians, I’m only one degree of separation away from people that still hold first-hand memories of him. This is why I decided to speak with some of those people.

Martin was born in Hobart in 1967 to Maurice and Carleen Bryant. Even as a child, he proved to be difficult. One report states that when he was little, his mother would tie him to the front porch area of the house, like a dog, to stop him from running off.

Jen Smith, who was a resident of nearby Eaglehawk Neck at the time, had a friend that went to school with Bryant. They told Smith that “he was cruel to the other kids so his mother kept him away from them.”

A psychiatric report, written by Paul E. Mullen and given at Bryant’s Crown Court case, backs this up. In the report it says that throughout his school years, Bryant would disrupt his classmates and take pleasure in seeing their discomfort. He was suspended because he had violent outbursts and would torment vulnerable kids. When he was 10 he spent several months in the burns unit at the local hospital, recovering from injuries he sustained while playing with fireworks. He was a bully to his sister because she was brighter than him and she had plenty of friends. And he had a penchant for torturing animals.

Hobart comedian Mick Davies grew up as Bryant’s neighbour, with just a small, barely-used laneway dividing their houses. “I just remember he was really weird,” he recalled. “Because he was in his twenties and still talking to me about Nintendo games and stuff. He was talking about how he had a Barbie Nintendo game; he said to me ‘Do you wanna swap some games?’ and I was like ‘Ahh, nah. I don’t want Barbie. I’m not into that.’”

Davies remembers having a crew with all the local kids in the neighbourhood, who were always running around and playing. Adult Bryant would often be in the bushes, he said, watching them. They’d call out to him: “We know you’re there Martin.”

And Davies’s father, Frank, remembers the day Bryant shot all the parrots in the area.

“When we first moved here there were a lot of nectarine trees. Fruit was so abundant we didn’t know what to do with it,” he said. “Every year the parrots used to come and feast on it; it was a paradise for those parrots. And his father had bought him an airgun, and he shot all the parrots. They never ever came back. Never once since have I seen a parrot in our trees.”

“I seem to remember reading that the first thing he said when [the police] got ahold of him was, ‘How many did I kill?’” he added, echoing others I spoke to who recalled Bryant saying the same thing. “I mean, to him, shooting people wasn’t that much different to shooting rosella parrots.”

After Bryant left school he was placed on a disability pension for various psychological reasons, according to the psych report. To make extra money, he’d ask around at the local neighbourhood for any odd jobs, such as lawn mowing.

My mum remembers him coming around to our house and either “trying to sell pegs, or mow the lawns, or paint our house number on the street outside.”

“He was just this weird, shy person,” she said.

There were some particularly strange events and circumstances that surrounded Bryant during his twenties. First, on one of his odd job searches, he became friends with an heir to a fortune. Fifty-four-year-old Helen Harvey was the granddaughter of the general manager for the Tattersall’s gambling lottery empire, and she and Bryant became such good friends that in 1991 she bequeathed everything to him—including a 29-hectare farm in Copping, her Clare Street Mansion, and the Tattersall’s income—in the event of her death.

Harvey was known for driving very slowly when she was with Bryant, cruising at a top speed of 60 kilometres per hour because of his nasty habit of grabbing the steering wheel. On the evening of 20 October 1992, they were driving along a road when they hit an oncoming car.

Jen Smith remembers that night. “I know a little about the accident when Helen Harvey was killed because my [current] partner, Buck, was the first one on the scene at the time,” she said.

Buck was driving with his step daughter and a friend when they came across the accident.

“So they went to the cars and Buck went to the one where Bryant and Harvey were, and it was obvious that she was completely gone. There were a couple dogs in the back that had been knocked out, and Bryant was knocked out at that point too.”

Harvey was confirmed dead at the scene, and, in accordance with her will, Bryant became a millionaire virtually overnight. His newfound fortune granted him the ability to go on a lot of overseas and interstate trips.

Then there was Bryant’s father’s death. Maurice had taken over the handling of the Copping farm and on August 13, 1993, a neighbour found a note pinned to the front door of the farmhouse that read, “Call the police”. Local fire brigade and police officers combed the 29-hectare property for two days in search of Maurice—all while Bryant was there at the farm with them, trying to impress the officers by making them laugh and asking out the women.

They eventually found his body, drowned in a shallow dam.

Bryant and his father occasionally went scuba diving together—they’d purchased their own gear—and Maurice had drowned with his son’s weight belt wrapped across him diagonally like a sash. Also in the dam were the carcasses of several sheep. A police recruit who had grown up on a farm pointed out that sheep never drink from water courses in a Tasmanian winter or spring, and rarely fall in.

Maurice’s death was ultimately ruled unnatural and Martin again inherited a large amount of money. Maurice had filled out his own will and left his son all of his superannuation: a total of $250,000.

With his huge sums of money, Bryant started stockpiling guns and hiding them around his house.

Hobart local Amanda Bergman, who used to work at the bar that Martin Bryant would frequent in the year leading up to the massacre, also remembers him.

“The bar I was working at was in the Sheraton Hotel, now the Grand Chancellor. It was open all day and then transitioned into an evening bar,” Bergman said. “Bryant started coming in for High Tea on occasion with his then-girlfriend and sometimes other guests. I remember he’d pay for everyone and make a show of it.”

Bergman was 20 at the time. Bryant’s girlfriend was 16. He was 27. Whenever she saw him at the bar with his teenage girlfriend, she said, his manner was noticeably off.

“The first time I served him I was working with an older staff member,” she said. “She [the older staff member] was usually good at working with our more unusual customers but she specifically asked me if I could serve him. She said he made her feel ‘really uncomfortable.’”

“I remember going up to his table and immediately noticing he had really different eye contact: moving, but then he’d stare for longer. It was quite unnerving. He was also dropping swear words rather awkwardly and inappropriately, like someone who doesn’t swear much. He was really hard to read.”

The final time that Bryant was back in his old childhood neighbourhood was about two weeks prior to the massacre. Davies remembered that he was “wearing white clothes like he was out of Miami Vice or something.”

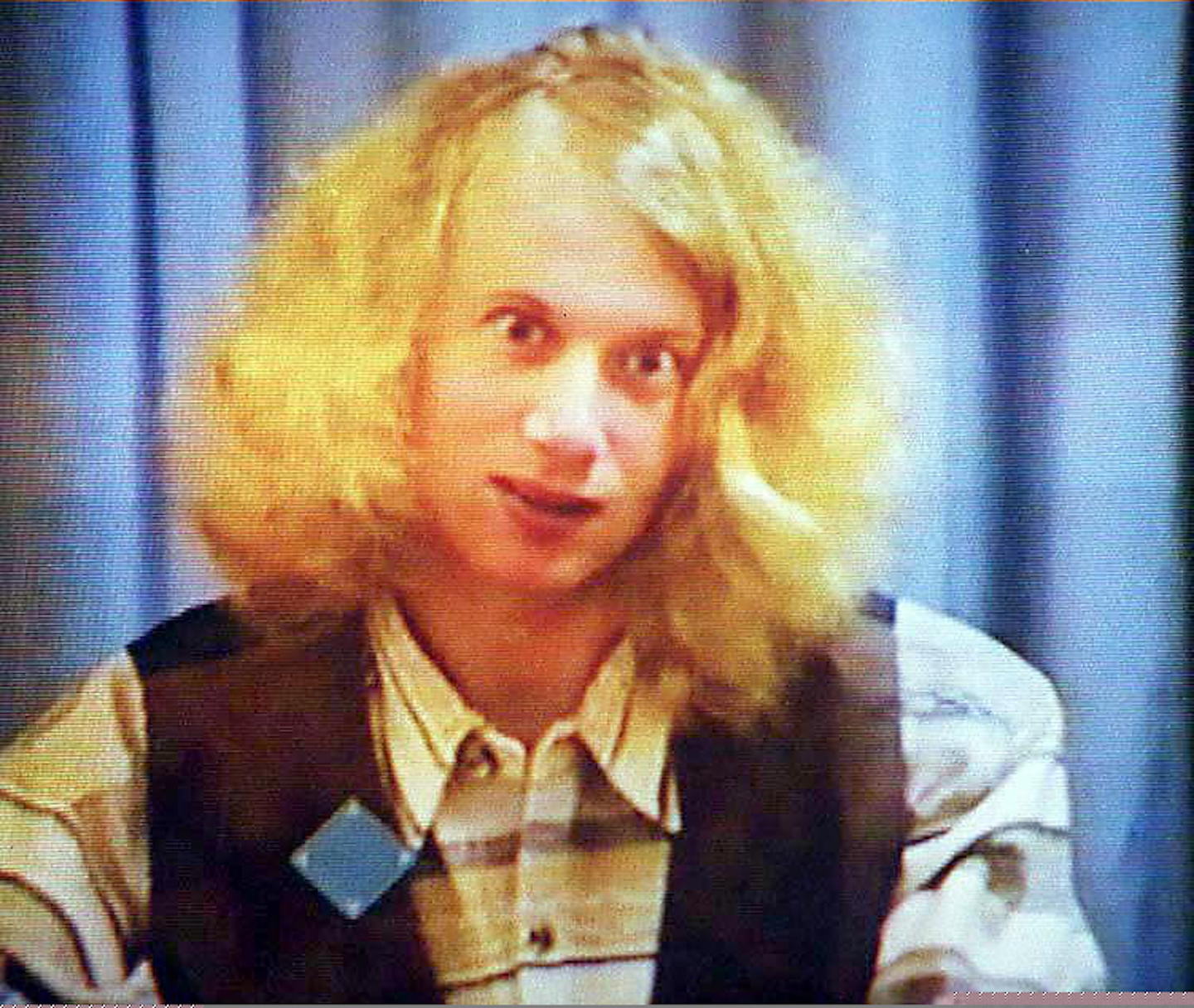

“It was just so striking how he looked, with the long blond hair and really well-dressed. Because we only knew him as a total dipshit,” he said.

Bergman remembers the day of the massacre vividly. She clocked in at work for the afternoon shift and there were no customers. Word had got out, and over the next few hours the media outlets started recounting what had happened. They gave the shooter’s description: “Long blonde surfer hair, blue eyes, late 20s.”

“I started to think it was the guy from the bar, but thought I was just being dramatic,” Bergman recalled. “When they released the picture on the front of [the local newspaper] I was shocked. It was exactly who I thought it was.”

Smith also remembers the day. “I was living in Eaglehawk Neck at the time, working as a volunteer ambo, and this dickhead up the road who was associated with the fire brigade came down and said, ‘Oh there’s some bloke down at Port Arthur shooting everyone and the fire brigade is going down there to look for him.’ My partner just looked at him and said ‘I’m not going down there in bright orange overalls to look for a shooter.’ And we just thought ‘he’s full of shit’ because that doesn’t happen.”

The Port Arthur massacre ultimately prompted Australia’s conservative Prime Minister John Howard to transform gun control legislation across the nation, working with the different states and territories to introduce significantly stricter gun laws. But before the shooting, Smith remembered how easily available guns were in Tasmania—especially down on the Peninsula.

“Everyone had guns!” she told me. “We had a semi-automatic 22 rifle, just to shoot rabbits. I remember someone saying they were really surprised that one of the staff didn’t just have a gun in the boot and take him out, because everyone down that way had guns in their boots—in case you were driving home at night and you ran over a wallaby and needed to finish it off. There was this massive gun culture. I don’t remember how we got ours—off a mate I think—but there was no tracking of it. Nothing. Nowadays to get a gun license you gotta be a member of a gun club or a farmer. You gotta have a decent reason.”

Smith sighed. “The massacre destroyed Tasmania’s innocence. We were this sleepy little backwater place.”

Below are the names of Martin Bryant’s victims, along with their ages.

Winifred Joyce Aplin, 58; Walter John Bennett, 66; Nicole Louise Burgess, 17; Sou Leng Chung, 32; Elva Rhonda Gaylard, 48; Zoe Anne Hall, 28; Elizabeth Jayne Howard, 26; Mary Elizabeth Howard, 57; Mervyn John Howard, 55; Ronald Noel Jary, 71; Tony Vadivelu Kistan, 51; Leslie Dennis Lever, 53; Sarah Kate Loughton, 15; David Martin, 72; Noelene “Sally” Joyce Martin, 69; Pauline Virjeana Masters, 49; Alannah Louise Mikac, 6; Madeline Grace Mikac, 3; Nanette Patricia Mikac, 36; Andrew Bruce Mills, 39; Peter Brenton Nash, 32; Gwenda Joan Neander, 67; William Xeeng Ng, 48; Anthony Nightingale, 44; Mary Rose Nixon, 60; Glenn Roy Pears, 35; Russell James Pollard, 72; Janette Kathleen Quin, 50; Helene Maria Salzmann, 50; Robert Graham Salzmann, 57; Kate Elizabeth Scott, 21; Kevin Vincent Sharp, 68; Raymond John Sharp, 67; Royce William Thompson, 59; Jason Bernard Winter, 29