Frida Kahlo once said, “I am my own muse. I am the subject I know best.” It’s a sentiment that also eloquently describes Martine Gutierrez, a transgender Latinx artist who routinely performs the triple roles of subject, maker, and muse in her own eclectic body of work.

By establishing a practice of full autonomy, wherein Gutierrez conceptualizes and executes every detail on both sides of the camera, the artist has taken complete control of her narrative. For her latest exhibition, Indigenous Woman, Gutierrez created a 146-page art publication (masquerading as a glossy fashion magazine) celebrating “Mayan Indian heritage, the navigation of contemporary indigeneity, and the ever-evolving self-image,” according to the artist’s “Letter From the Editor.”

Videos by VICE

“I was driven to question how identity is formed, expressed, valued, and weighed as a woman, as a transwoman, as a Latinx woman, as a woman of indigenous descent, as a femme artist and maker? It is nearly impossible to arrive at any finite answers, but for me, this process of exploration is exquisitely life-affirming,” she writes.

Gutierrez uses art to explore the intersections of gender, sexuality, race, and class as they inform her life experience. The Brooklyn-based artist uses costume, photography, and film to produce elaborate narrative scenes that combine pop culture tropes, sex dolls, mannequins, and self-portraiture to explore the ways in which identity, like art, is both a social construction and an authentic expression of self.

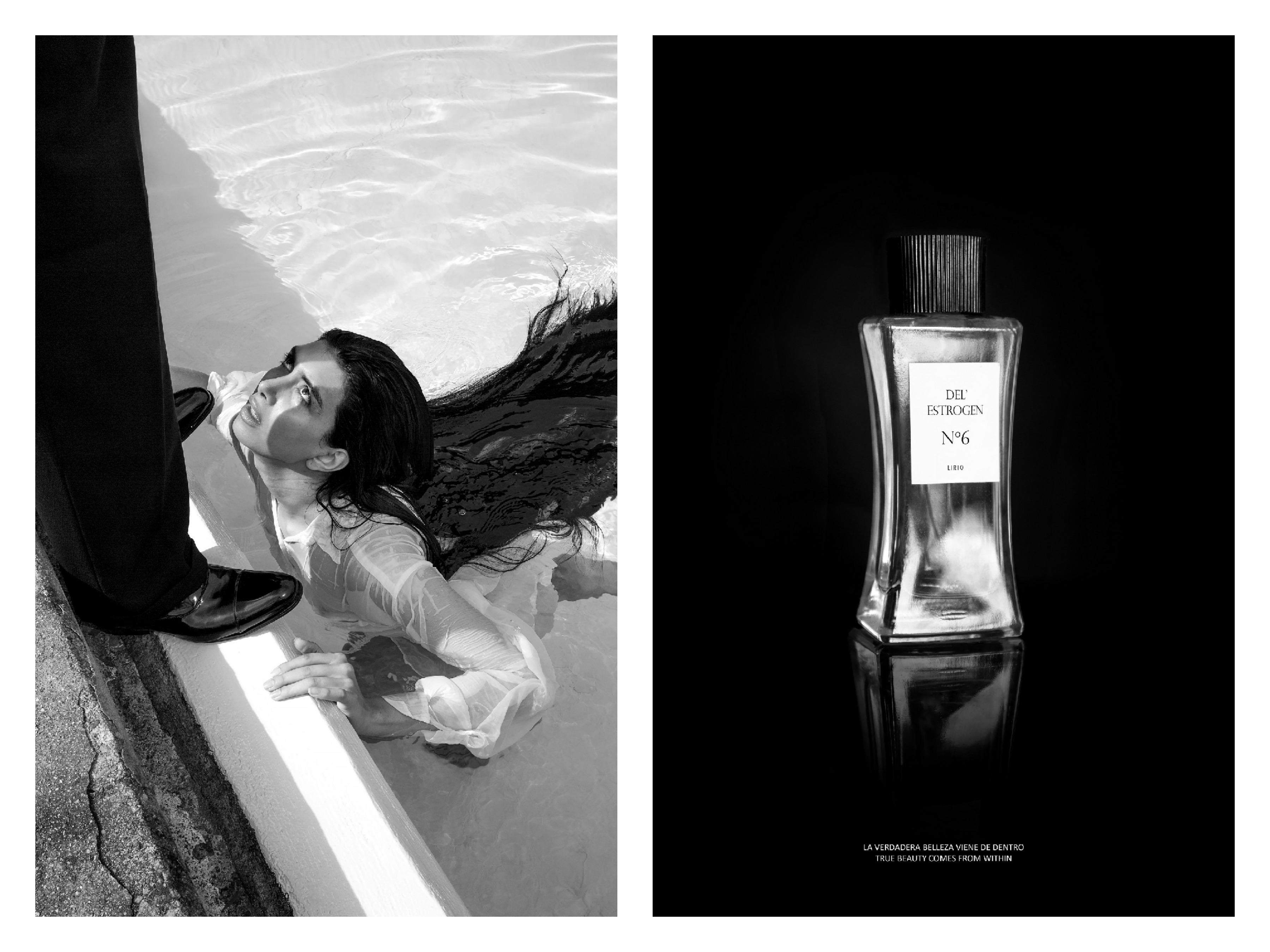

Fashion editorials and beauty features with titles like Queer Rage, Masking, and Demons pepper the pages of Indigenous Woman, alongside advertisements for faux products like Blue Lagoon Morisco sunless bronzer, paired with the tagline “Brown is Beautiful.” Gutierrez subverts the traditional cisgender white male gaze while simultaneously raising questions about inclusivity, appropriation, and consumerism.

While her exhibition is on view at Ryan Lee Gallery in New York, VICE caught up with Gutierrez to talk about her masterful interrogation of identity.

VICE: What metaphorical hats did you wear while creating Indigenous Woman?

Gutierrez: Everything! Most people don’t take into consideration all of the minute details that make up an image of someone who doesn’t look like me or doesn’t exist in the same world I do, even though it is me. I am the creator, founder, editor in chief, grant writer [laughs]. There really wasn’t a budget [for the magazine], which is probably why it took three years to make.

From a fashion magazine standpoint, it’s easy to name those categories because they exist to be noted in that format. Here I could highlight this part of my practice that had always remained silent: doing hair, makeup, styling, any kind of graphic design, photography, the modeling, location scouting. What’s less glamorous is that I’m also the crew. I’m the schlepping person.

People just think it’s a glamorous image, and that is what I want. I want it to feel easy. I want you to not get hung up on the raw edges of something—because there are a lot of them, I’ve just smoothed them all down. People have always held my work to [the fashion] industry, because I do a glossy finish innately. I think it shows great care and attention.

Could you talk about how your early work as an avant-garde performance artist relates to your role as a photographer/model?

I look at my photoshoots as performances—they are just hyper-controlled and private. Because my practice is so solitary, the live performances are structurally similar to my shoots and hold the ephemeral beauty of transforming [and turn it] into a feeling. The experience can linger in you the way an image can’t. Live performance is internalized, so it can manifest in dreams or be remembered until death.

There’s a line in the magazine about how you devolved from an emo shaman into some sort of femme fatale—and you’re praised for it. Can you speak about the role of glamour in your work?

That high school picture of me—I feel like no one believes me. I’ll look through the magazine with a curator, and when we get to that image I’m always like, “That’s a school picture,” and they’re like, “Wait, that isn’t a photo shoot? This isn’t some recreated moment?”

No, it’s real, and that’s what’s so funny to me. The whole magazine is real in a fantastical and reimagined way. It is taking elements of my life and elements of my identity that are confusing and hard for even me to chew on, and attempting to share them.

I love the interview you did for the magazine. When you quoted a line from the HBO movie Gia with such precision and expertise, it made me laugh and realize that the conversation about art can often be humorless and dry.

I think there’s an air of intellectualism that art needs to function. There needs to be rhetoric for the art world, for the museums, for the public who goes to these functions to say, “This is valid because…”

I don’t know if I am trying to change that. I just know I don’t like to play that way. We’re living in an era where my existence is political whether I want to be or not. It’s really hard and emotionally taxing, and humor is my savior.

In the feature Masking, you create elaborate photographs of at-home facials that are reminiscent of the late work of Irving Penn, where you use fruit, flowers, and beauty treatments to build a wild, new face. What was the inspiration for that series?

Masking was the first opportunity to not even be human, to disguise the conversation of gender, and to get away from identity politics. I had just done a body of work about mannequins and so much of it was about holding myself. I was doing the same thing—painting on my face with colors we assume are natural: red on the lips, blue on the eyes, flesh everywhere else, cover your beard, accentuate your better feminine qualities. It’s exhausting. It lost its fun and I lost motivation to keep making work in that way.

I wanted to do a series that could allow me to gain wellness from the practice of it. I was thinking about the stuff [that happens] after a photoshoot—washing it all off: the toner, cream, olive oil, honey, matcha, mud, and the facial masks that help me look and feel good in the real world. I was like, What if that’s the makeup? It became exciting to build an identity based on alien forms, looking for shapes and textures and colors in fruit, flowers, and vegetables that could create what we recognize as a face: two things above and a line below. We are trained to look for faces, and once we see faces we are trained to take them apart and ask, “What kind of person is it?”

Is it a man or a woman? How old are they? Where are they from? Building that narrative, we look at how people dress, how they walk, talk, and carry themselves. All of those markers are so connected to the binary of gender and how we separate people into one or the other. There’s so little opportunity not to be sifted into those two categories, and Masking was the opportunity to treat this as alien, without being sci-fi.

What’s the significance of going beyond the binary?

We look at things as black and white when there’s so much grey. Even people that think they’re in the black or in the white—they have a foot in the grey. We all do. It’s impossible not to.

Could you speak about the indigenous perspective?

That’s part of the question: Do I have that? I don’t think I do. I am an American, born in Berkeley, California, raised in Oakland and Vermont, and living in New York City. I have an Amerindigenous perspective. It is the perspective of both my parents’ cultures and yet neither, because it is my own mess. I’ve been called every iteration of a “half breed,” and it’s no doubt the origin of my questioning. I’m asking what signifies a real, authentic, native-born woman?

It’s a critique and a simultaneous investigation of what claim over these labels, stereotypes, and iconographies I have. My authenticity has never been to exist singularly, whether in regard to my gender, my ethnicity, or sexual orientation. My truth thrives in the gray area, but society doesn’t yet allow an open consciousness to celebrate ambiguity, and we are told who we should be. But it’s up to you to consider everything and be open, otherwise how will you know if your life is real or just a reenactment?

In the feature Demons, you cast yourself as Aztec, Mayan, and Yoruba deities to examine how the sacred feminine in indigenous cultures has been portrayed by the West. How did this series come into being?

I went into it thinking I was going to call it Goddesses, because that’s what my community calls trans women. We are either called “angels” or “goddesses,” and I guess that’s how we’re looked at. We’re otherworldly. I was like, Let’s look at some goddesses from my ancestry. What [role] did they serve? The closest things to me are these deities. I like that word. It feels ungendered for an individual in a place of spiritual power.

In [ancient Mayan] literature, they were referred to as demons. Maybe the establishment doesn’t think of these as people existing. It’s mythology. But for me—the person trying to relate to an ancient person that represented their community—they were seen as a demon, and even my reaction [to that] is connected to colonialism. That negativity catapults you into the underworld. [The Mayans] called it Xibalba, the underworld, and that’s where a lot of these figures reigned.

I found it both shocking and exciting. Especially because I had already started making hair crowns for these deities, and I was like, Oh you girls are going to be a little different. You’re a little demonic. But it’s such a mind frame. I don’t have a clear understanding of what they did, because whether it was Mayan or Aztec, everything that we have that’s taken down is translated into English, and the interpretation of it, because it is Western, is immediately filtered through the eyes of the people cataloguing it.

That would be like if I was writing about Christian pop music or competitive cheerleading. It would be so outside of anything I am familiar with, yet I have the power of authority to say, “This is what it is,” and that’s the reference. The truths of history are daunting to me because of that. What is that saying about how there are many truths? [Laughs]. I think it’s so true.

How does identity and representation drive you as an artist?

I can only speak on my life, my experiences. I feel like most of the questions I pose or the roles I assume are roles that I am grappling with in life. That’s why they feel so important to manifest, and in manifesting them, it helps me move on. Not always, but I have learned that the practice of image, video, or music making is to see something outside of myself or how society doesn’t see me—and it somehow comes true. It’s like making a wish, or putting a message in a bottle, and [it helps] you let go of the latter one.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Indigenous Woman is on view at Ryan Lee Gallery, New York, through October 20, 2018.

Follow Miss Rosen on Instagram.