On the morning of May 29, 2014, an overcast Thursday in Washington, D.C., the general counsel of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Robert Litt, wrote an email to high-level officials at the National Security Agency and the White House.

The topic: what to do about Edward Snowden.

Videos by VICE

Snowden’s leaks had first come to light the previous June, when the Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald and the Washington Post’s Barton Gellman published stories based on highly classified documents provided to them by the former NSA contractor. Now Snowden, who had been demonized by the NSA and the Obama administration in the intervening year, was publicly claiming something that set off alarm bells at the agency: Before he leaked the documents, Snowden said, he had repeatedly attempted to raise his concerns inside the NSA about its surveillance of U.S. citizens — and the agency had done nothing.

Some on the email thread, such as Rajesh De, the NSA’s general counsel, advocated for the public release of a Snowden email from April 2013 in which the former NSA contractor asked questions about the “interpretation of legal authorities” related to the agency’s surveillance programs. It was the only evidence agency personnel said they found that even came close to verifying Snowden’s assertions, and De believed it was enough to call Snowden’s credibility into question and put the NSA in the clear.

Litt disagreed.

“I’m not sure that releasing the email will necessarily prove him a liar,” Litt wrote to De; Caitlin Hayden, then the White House National Security Council spokesperson; and other officials. “It is, I could argue, technically true that [Snowden’s] email… ‘rais[ed] concerns about the NSA’s interpretation of its legal authorities.’ As I recall, the email essentially questions a document that Snowden interpreted as claiming that Executive Orders were on a par with statutes. While that is surely not raising the kind of questions that Snowden is trying to suggest he raised, neither does it seem to me that that email is a home run refutation.”

Within two hours, however, Litt reversed his position, and later that day, the email was released, accompanied by comment from NSA spokesperson Marci Green Miller: “The email did not raise allegations or concerns about wrongdoing or abuse.”

Five days later, another email was sent — this one addressed to NSA director Mike Rogers and copied to 31 other people and one listserv. In it, a senior NSA official apologized to Rogers for not providing him and others with all the details about Snowden’s communications with NSA officials regarding his concerns over surveillance.

The NSA, it seemed, had not told the public the whole story about Snowden’s contacts with oversight authorities before he became the most celebrated and vilified whistleblower in U.S. history.

Hundreds of internal NSA documents, declassified and released to VICE News in response to our long-running Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, reveal now for the first time that not only was the truth about the “single email” more complex and nuanced than the NSA disclosed to the public, but that Snowden had a face-to-face interaction with one of the people involved in responding to that email. The documents, made up of emails, talking points, and various records — many of them heavily redacted — contain insight into the NSA’s interaction with the media, new details about Snowden’s work, and an extraordinary behind-the-scenes look at the efforts by the NSA, the White House, and U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein to discredit Snowden.

The trove of more than 800 pages [see the pdf at the end of this story], along with several interviews conducted by VICE News, offer unprecedented insight into the NSA during this crisis within the agency. And they call into question aspects of the U.S. government’s long-running narrative about Snowden’s time at the NSA.

* * *

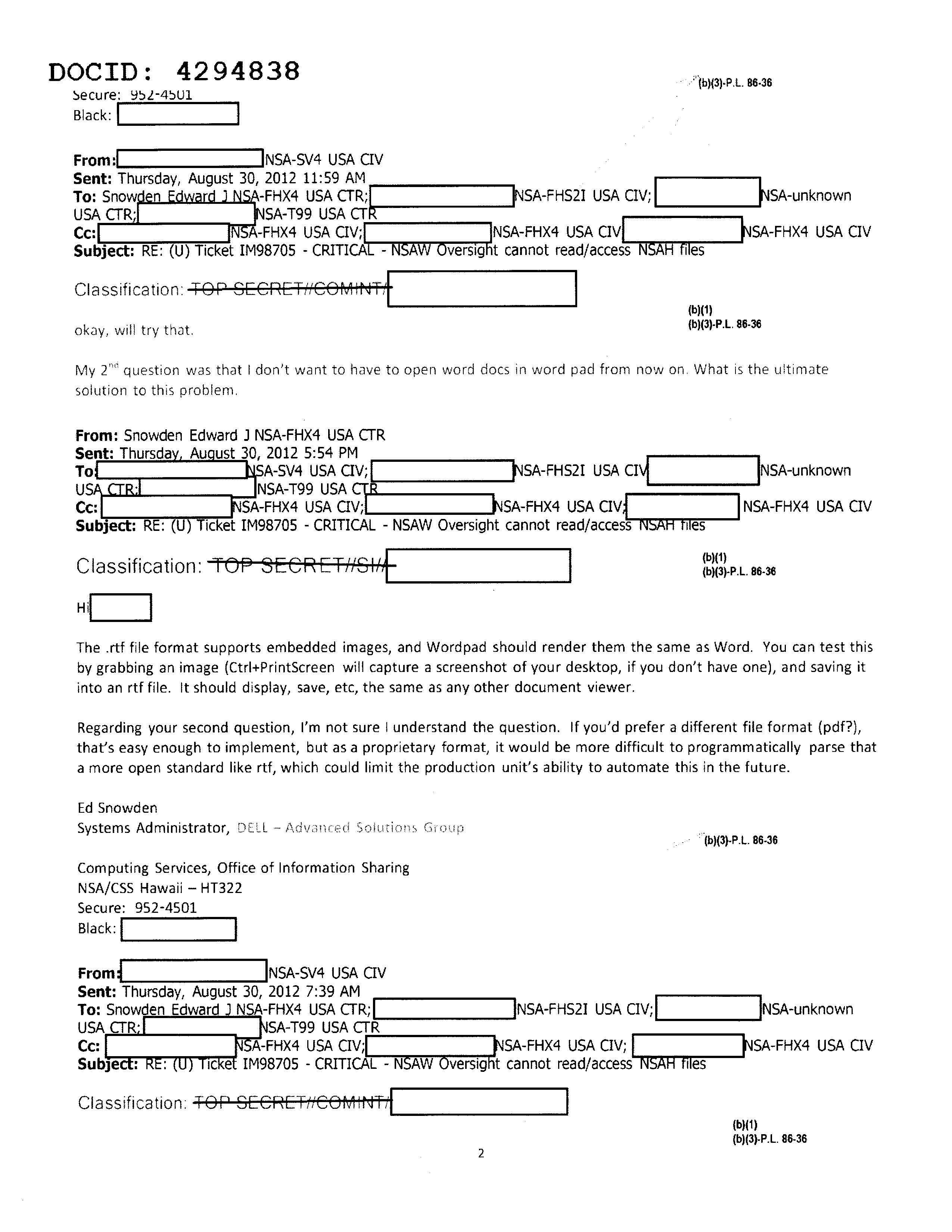

The Obama administration spent the spring of 2014 engaged in highly classified talks centered around three events: Snowden’s testimony to European Parliament in March, the release of a 20,000-word April 2014 Vanity Fair story about Snowden, and his first U.S. television interview, with NBC News’s Brian Williams, in May.

In all three instances, Snowden insisted that he repeatedly raised concerns while at the NSA — and that his concerns were repeatedly ignored. In his testimony to the European Parliament on March 7, he was asked whether he “exhausted all avenues before taking the decision to go public.”

“Yes,” he said. “I had reported these clearly problematic programs to more than 10 distinct officials, none of whom took any action to address them. As an employee of a private company rather than a direct employee of the U.S. government” — Snowden had been a contractor with Booz Allen Hamilton when he leaked the documents — “I was not protected by U.S. whistleblower laws, and I would not have been protected from retaliation and legal sanction for revealing classified information about law breaking in accordance with the recommended process.”

Four days after Snowden’s testimony, the chief of the NSA’s counterintelligence investigations division sent an email with the subject line “Snowden Claims” to Richard Ledgett, the deputy director of the NSA and the head of the so-called Media Leaks Task Force established the previous year to investigate Snowden’s leaks. Also copied were Leoinel Kemp Ensor, the NSA’s security chief, and other NSA officials.

“As requested we, ADS&CI [the NSA’s associate director security & counterintelligence] and FBI, have conducted extensive research into [Snowden’s statement to the European Parliament],” the NSA counterintelligence official wrote. “This included a review of all interviews and case material to include all paperwork and interviews collected/conducted with contractors Dell and Booz Allen Hamilton.”

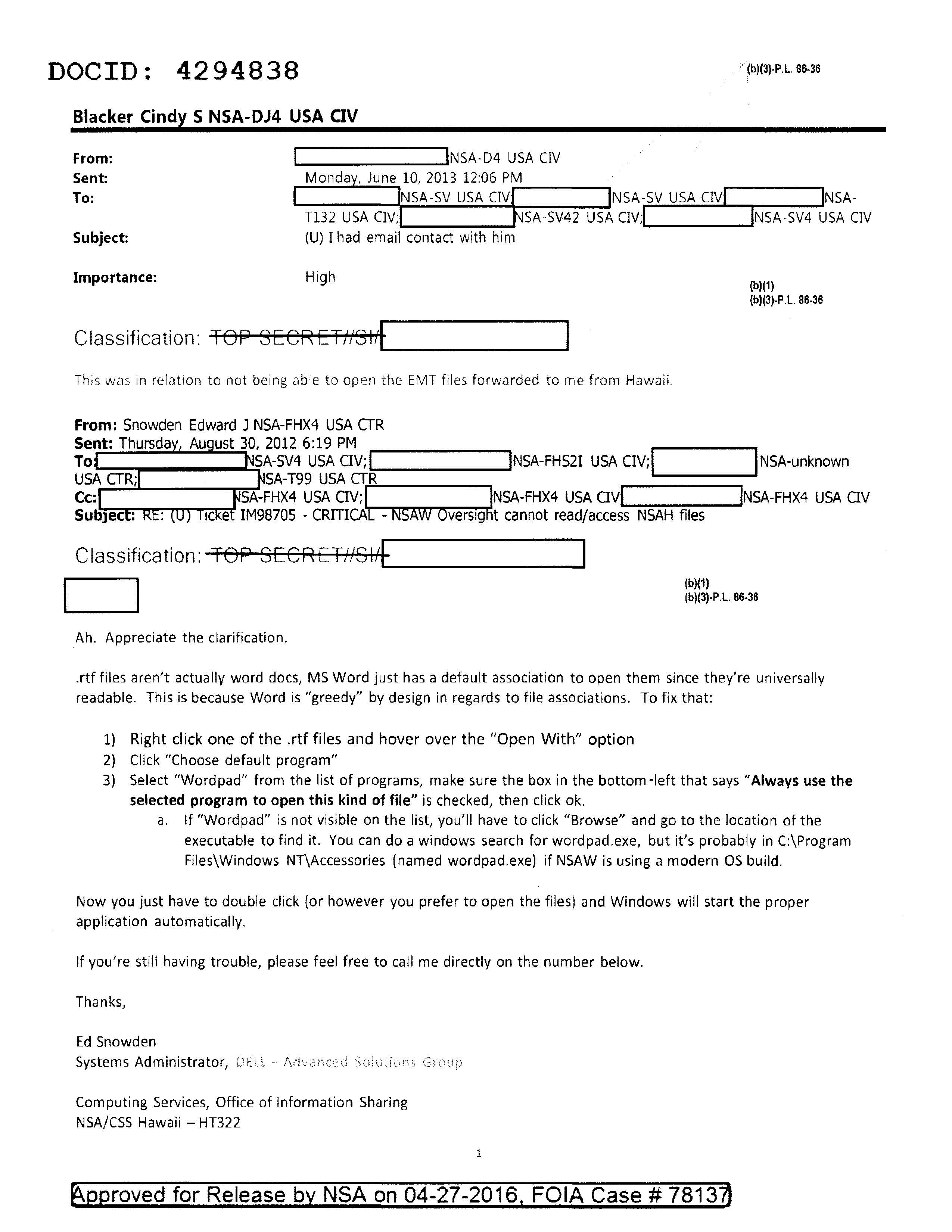

In several emails, Snowden, as a systems administrator for Dell in August 2012, provided NSA officials with tech support on FISA templates. (FISA, or the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, dictates a legal framework for wiretapping and other surveillance.)

“Our findings are that we have found no evidence in the interviews, email, or chats reviewed that support his claims,” the NSA official continued. The official did, however, acknowledge that Snowden had at the very least brought up privacy while at the agency. “Some coworkers reported discussing the Constitution with Snowden, specifically his interpretation of the Constitution as black and white, and others reported discussing general privacy issues as it relates to the Internet.”

Because none of the people interviewed by the NSA in the wake of the leaks said that “Snowden mentioned a specific NSA program,” and “many” of the people interviewed “affirmed that he never complained about any NSA program,” the NSA’s counterintelligence chief concluded that these conversations about the Constitution and privacy did not amount to raising concerns about the NSA’s spying activities.

That was the basis for public assertions — including those made by Ledgett during a TED talk later that month — that Snowden never attempted to voice his concerns about the scope of NSA surveillance while at the agency.

* * *

Snowden declined to answer a number of very specific questions for this story. His attorney, Ben Wizner of the ACLU, told VICE News that Snowden is “ambivalent” about discussing the issues raised by the NSA documents because he doesn’t trust the NSA’s motives for releasing them.

“[Snowden] believes the NSA is still playing games with selective releases, and [he] therefore chooses not to participate in this effort,” Wizner said. “He doesn’t trust that the intelligence community will operate in good faith.”

‘The lawyer who responded to Snowden’s inquiry considered calling him, because the inquiry was out of the ordinary.’

Due to the review process conducted by the government before releasing requested documents, FOIA releases are “selective” by their very nature. A series of guidelines determines what the government can and can’t keep from the public, but ultimately the interpretation of those guidelines can be relatively subjective. It is not a process unique to the NSA.

What’s remarkable about this FOIA release, however, is that the NSA admitted it removed the metadata in emails related to Snowden. In a letter disclosed to VICE News Friday morning following inquiries we made about discrepancies in some of the emails turned over to us, Justice Department attorney Brigham Bowen said, “Due to a technical flaw in an operating system, some timestamps in email headers were unavoidably altered. Another artifact from this technical flaw is that the organizational designators for records from that system have been unavoidably altered to show the current organizations for the individuals in the To/From/CC lines of the header for the overall email, instead of the organizational designators correct at the time the email was sent.”

* * *

Snowden’s email, which would go on to spark so much debate from the NSA to the Department of Justice to Congress to the White House, was inspired by a question on a training test. The NSA portrayed it as an innocuous query that elicited a direct response when it released the email in 2014. But the declassified documents tell a different story, with multiple people from different departments involved in formulating an answer.

On April 5, 2013 — a year before the Vanity Fair story came out — Snowden clicked the “email us” link on the internal website of the NSA’s Office of General Counsel (OGC) and wrote, “I have a question regarding the mandatory USSID 18 training.”

United States Signals Intelligence Directive 18 encompasses rules by which the NSA is supposed to abide in order to protect the privacy of the communications of people in the United States. Snowden was taking this and other training courses in Maryland while working to transition from a systems administrator to an analyst position. Referring to a slide from the training program that seemed to indicate federal statutes and presidential Executive Orders (EOs) carry equal legal weight, Snowden wrote, “this does not seem correct, as it seems to imply Executive Orders have the same precedence as law. My understanding is that EOs may be superseded by federal statute, but EOs may not override statute.”

About 20 minutes after Snowden sent the email, an OGC office manager forwarded it to the Signals Intelligence Oversight and Compliance training group — the people who had designed the test.

“OGC received the question below regarding USSID 18 training but I believe this should have gone to your org instead,” the office manager wrote. “Can you help with this?” The office manager also cc’d Snowden.

But the next working day, April 8, the email and question were sent right back to the OGC. The woman who did this would later explain to NSA investigators, “Although I felt comfortable answering his question, I thought it was more appropriate for OGC to respond since the authority documents include legalities and the individual wanted them ranked in precedence order.”

So she forwarded the email to two OGC attorneys who “had recently provided the hierarchy of the authorities” in the training program to which Snowden was referring.

At least one of those lawyers said she felt Snowden’s email was unusual. A Security & Counterintelligence official wrote in an email a year later that officials had spoken to “the lawyer who responded to Snowden’s inquiry and she remembered considering calling Snowden since the inquiry was out of the ordinary. However, she decided not to and instead in her email invites him to call her if he wanted further discussion. She does not recall any actual telephonic contact by Snowden.”

When the lawyer responded to Snowden, she cc’d five people: three in the Oversight and Compliance Office (referred to at the agency with the letters S.V.), and two other OGC lawyers.

The lawyer who responded to Snowden explained to him in an email, “Executive Orders (E.O.s) have the ‘Force and effect of law.’ That said, you are correct that E.O.s cannot override a statute.”

Snowden read this email, then put it in a folder in his inbox.

In a recent interview with VICE News, Litt, the person who in 2014 had expressed misgivings about the email before reversing himself, said: “To the extent Snowden was saying he raised his concerns internally within NSA, no rational person could read this as being anything other than a question about an unclear single page of training.”

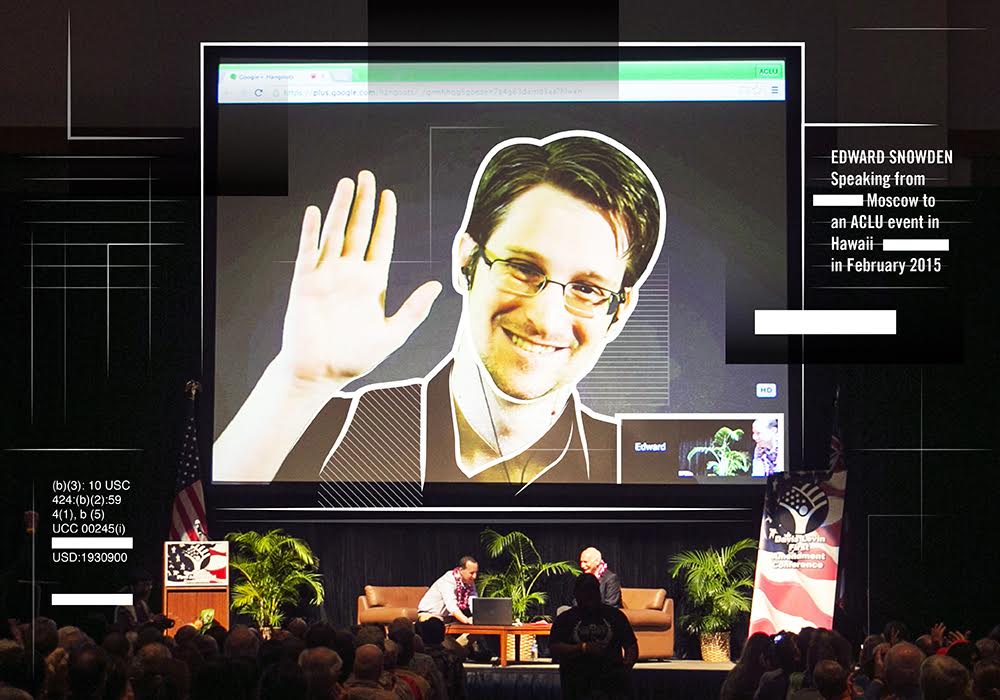

Less than six weeks after he sent the email, Snowden would be on a plane to Hong Kong with thousands of highly classified government documents. In a report on the subsequent investigation, a special agent pointed out what Snowden had already done by the time he sent his email.

“It should be noted this is four months after contacting Glenn Greenwald (according to Greenwald) and three months after contacting Laura Poitras (according to Poitras and Greenwald),” the special agent wrote. (Poitras is the filmmaker Snowden originally contacted along with Greenwald and Gellman.) “So this email is not evidence that he tried to raise concerns about NSA procedures through official channels before turning to the media.”

It is not clear whether Snowden had yet shared any documents with the journalists when he wrote the email.

* * *

In April 2014, the month after he testified before the European Parliament, Snowden again challenged the NSA’s public narrative about his failure to raise concerns at the agency. In advance of the publication of the Vanity Fair story, the magazine posted a preview online on April 8.

“The NSA… not only knows I raised complaints, but that there is evidence that I made my concerns known to the NSA’s lawyers, because I did some of it through e-mail,” Snowden told the magazine. “I directly challenge the NSA to deny that I contacted NSA oversight and compliance bodies directly via e-mail and that I specifically expressed concerns about their suspect interpretation of the law.”

Later that day, someone from the Media Leaks Task Force circulated an email with the subject line, “FYSA: Snowden Allegation in Pending Vanity Fair Article.” (FYSA is an acronym for “for your situational awareness.”) A day later, Rogers, who had been NSA director for only a week, stated that he favored openness and transparency in the agency’s response to Snowden.

“Let’s be ready to be very public here,” Rogers wrote in an email to Ledgett; De; Ethan Bauman, the director of the NSA’s Office of Legislative Affairs; Frances Fleisch, the agency’s executive director; and other officials whose names were redacted. “If [Snowden’s] claims are factually incorrect and we do not have security concerns with the subject matter we should be very forthright in stating his claims are factually incorrect. I want us to do the coordination ASAP [versus] waiting for an article and then spending three weeks debating our way ahead.”

This was easier said than done. On the morning of April 10, a day before the full Vanity Fair article was published, someone at the NSA sent an email to Arlene Grimes in the agency’s office of public affairs, cc’ing several other officials, to recommend “the best way forward” in light of Rogers’ directive.

“One of the key issues in any response will be the degree of certainty we express on the specific issue of outreach by Snowden to express concerns,” the NSA official wrote.

Henceforth, the Media Leaks Task Force’s main mission would be to take “more proactive actions to undermine future and recurring false narratives” by Snowden, as one NSA official wrote. The task force could use Snowden’s email, the official said, to accomplish that goal by “contacting Vanity Fair BEFORE they publish and let them know that we plan to immediately and publicly challenge that assertion AND make clear that we warned Vanity Fair that the facts are wrong.”

To go forward with this plan, the NSA needed two things: Absolute certainty that Snowden had not communicated his concerns, and approval from the DOJ to release the email.

The NSA appeared to have neither.

Emails show that the DOJ preferred for Snowden’s email not to be publicly released. In addition, some in the NSA believed that additional investigations were necessary to ensure Snowden had not raised concerns.

“We need great certainty about whether or not there is/was additional correspondence before we stake the reputation of the Agency on a counter narrative,” a person from the task force replied in an email addressed to counterintelligence, the legislative affairs office, and the office of general counsel on April 9. “I am going to trigger an action for the appropriate organizations to do an e-mail search [redacted] to affirm that there is no further correspondence that could substantiate Snowden’s claim.”

Shortly before 6:30 the next morning, someone from the task force sent an email to the chief of the NSA’s counterintelligence division.

“One last question that woke me up last night, do you know if [redacted] who received the April [2013] e-mail from Snowden was specifically asked if she received any further correspondence?” the person wrote. “I ask only because there probably isn’t anyone checking her e-mail queue since she is now retired. I’m just trying to be as sure as possible we’ve asked the right people and checked the right places for any potential surprises.”

The woman in question was the lawyer at the OGC who had addressed Snowden’s email and its query about legal hierarchies. (She had retired from the NSA in the interim.) The counterintelligence chief wrote that the woman had not recalled any interaction when she was questioned by the NSA in the wake of Snowden’s leaks, but that he would “triple check.”

The counterintelligence chief got in touch with the retired lawyer, and about an hour after their conversation, he sent another email.

“Spoke with [redacted] at home,” the chief wrote. “She said no telephonic contact after the email. Also confirmed that Snowden did not reply to her response which matches what we see in the email. Our review of his email did not turn up any additional emails that match the description in the [Vanity Fair] article. I truly believe we have the right one. I have asked DOJ to call me so we can discuss the release issue [of the email]. I have heard that [redacted] is not happy that I am talking to DOJ, but I am not too concerned with that right now.”

“Thanks,” the task force official replied. “I’ll visit you when they put you in prison for talking to DOJ.”

Bauman, the director of the Office of Legislative Affairs, sent an email on the afternoon of April 10 to David Grannis, then the staff director for the Senate Intelligence Committee, and other congressional staffers alerting them to the pending Vanity Fair article. Bauman also provided them with a redacted copy of the Snowden email.

On April 11, Vanity Fair released its story. That afternoon, Ledgett sent an email to Teresa Shea, the director of signals intelligence — or SIGINT, which is responsible for decoding electronic communications — and a number of officials whose names were redacted. (Later that year, Shea left the NSA after BuzzFeed reported that she and her husband ran a SIGINT “contracting and consulting” business out of their home in what appeared to be a conflict of interest with her official NSA duties.)

‘I can’t give you 100% assurance there isn’t any correspondence that may have been overlooked.’

Ledgett’s email, with the subject line, “Vanity Fair Article With Fugitive – May Cause Additional Work,” said “the much anticipated Vanity Fair article with the fugitive is out…. Probably the most concerning issue in the article is the fugitives [sic] assertion that he raised complaints with NSA lawyers and oversight and compliance personnel.”

The scramble in the lead-up to the article’s publication to make certain Snowden hadn’t logged his concerns within the agency is especially notable in light of one fact: Ledgett had already said unequivocally that Snowden hadn’t raised any formal concerns — and he had said so in the article itself, having been interviewed well in advance of its publication. He added that if Snowden made his concerns known to anyone personally, they had not stepped forward to alert the NSA during the agency’s subsequent internal investigation.

The article, and Snowden’s assertion in it that he had repeatedly made his concerns known via email, was the catalyst for VICE News’ initial FOIA request, filed the same day the article preview was released. But the assertion did not prompt widespread media coverage at the time.

“The good news is that this article has not received any bounce and there have been no media queries today,” Grimes wrote on the afternoon of April 10.

Things would change six weeks later.

* * *

On the morning of May 23, 2014, Matthew Cole, then an investigative reporter with NBC News, sent an email to NSA public affairs. He wished to alert them to the network’s exclusive on-camera interview with Snowden, which would be his first with a U.S. television network. (The interview had first been revealed by the Washington Post a day earlier.)

“As you may have seen, NBC News will be airing a long interview with Edward Snowden,” Cole wrote in an email addressed to NSA spokesperson Vanee Vines and Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) spokesperson Shawn Turner. “Given that he makes plenty of claims in the interview, I have the enviable job of checking the veracity of said claims. Is it possible to discuss by phone at your earliest convenience?”

Vines asked him to put what he needed in writing.

“Let’s start with this one, but I will still need to have a follow up phone conversation,” Cole responded. “Can the NSA and/or DNI confirm or deny that Mr. Snowden sent emails to the NSA’s OGC or any other internal/agency legal compliance body? NBC News is aware that in the past NSA has denied that they can find any such emails.”

The same day, Cole submitted a short FOIA request to the NSA, asking for “any and all emails, documents, or any other form of communication” between Snowden and any legal authorities within the agency. Although VICE News and a number of other media outlets had already filed FOIA requests for the same documents, the NSA now began to discuss taking quick action because of the pending broadcast of NBC’s interview.

Vines was part of the team that had spent several weeks dealing with identical claims Snowden had made to Vanity Fair a month earlier, so she was well aware of the existence of Snowden’s lone email. But she was coy with Cole.

“What do you mean? An email about *what*?” Vines wrote to him before repeating an NSA statement from December 2013 saying that investigations found no evidence that Snowden ever brought up his concerns.

Cole responded by asking for the documents again, “based on more detailed claims in our interview.”

Vines immediately forwarded the exchange to Rajesh De, the NSA’s general counsel.

“[With] its story done, NBC is asking us to fact-check. Incredible,” Vines wrote. “We’ll get more info soon from the producer. In the meantime, there’s apparently a fresh claim about email the leaker [Snowden] allegedly sent to OGC or a compliance official.”

De, a staunch advocate for releasing Snowden’s email, informed Vines that the NSA had already been speaking to the White House about Snowden’s claims. He asked Vines to see if she could ferret out additional details from Cole about the interview.

Later that day, Feinstein, the chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, sent word over to the NSA that she expected a “forceful NSA response” to Snowden’s claims.

An agency official moved quickly to manage Feinstein’s demand.

“You can help temper expectations by making clear [to Feinstein] that we were not aware of this story before it was publicly advertised and until yesterday had not been contacted to respond to any issues,” an official on the NSA’s Media Leaks Task Force wrote to a recipient — both of their names were redacted — cc’ing several other officials and listservs. “We have not been and don’t expect to be given much if any detail beyond the public ‘teaser.’ We can only crystal ball so much, especially when the protagonist is not bound by facts or the truth.”

The following morning, De sent someone at NSA an email with the subject line “NBC/email.”

“I need very senior confirmation [Kemp/Moultrie) [a reference to the NSA’s director of security and Ron Moultrie, then the NSA’s deputy SIGINT director] that all possible steps have been taken to ensure there are no other emails from [Snowden] to OGC,” De wrote.

Those assurances apparently could not be provided — even though the agency had publicly been saying over the course of a year that no other relevant communications from Snowden existed.

“Raj, if you are looking for 100% assurance there isn’t possibly any correspondence that may have been overlooked I can’t give you that,” an NSA official, whose name was redacted, wrote in response to De. “If you asked me if I think we’ve done responsible, reasonable and thoughtful searches I would say ‘yes’ and would put my name behind sharing the e-mail as ‘the only thing we’ve found that has any relationship to [Snowden’s] allegation. Give [sic] Snowden’s track record for truth telling we should be prepared that he could produce falsified e-mails and claim he sent them. The burden then falls to us to prove he didn’t (you know how that will end).”

That morning, Hayden, the National Security Council spokesperson, sent an email to Vines, Stuart Evans at the DOJ, and Litt at the ODNI. That email has been entirely redacted. At about the same time, De emailed someone asking, “Why is DOJ weighing in on our obligations under privacy act?” which is an indication that the Department of Justice was interfering in the NSA’s decision to release Snowden’s email.

“I have no idea,” the person responded to De.

In the early evening of May 24, Rogers, the NSA director, suggested that the agency finally release Snowden’s email, which Rogers mistakenly said Snowden had addressed to the agency’s Inspector General (IG).

“I’d love to share the specifics of the only e-mail we have that [Snowden] sent to the IG which asked a very broad question on the hierarchy of law vs the direction in regulation and other publications and which never mentioned privacy concerns once,” Rogers wrote.

An NSA official offered up several options for dealing with NBC News, only one of which was left unredacted: “Option 1 — Engage NBC in dialog before their program airs about our factual understanding (a single outreach [from Snowden]… barely relevant to his claims).”

That’s the option Rogers chose.

Vines then sent a note about whether the NSA should release Snowden’s “ONE email to NSA OGC (and OGC’s response to his very benign question.” Included on the correspondence were officials from the NSA, the DOJ, and the White House. Vines noted that a number of news organizations had filed FOIA requests for any emails in which Snowden raised concerns, and if the NSA were to release the single email the agency said it found, it would need to be released “to all.”

Several responses by Hayden, De, and Litt followed and continued throughout the weekend; Hayden appeared to have enormous influence over whether the NSA could release the email.

On Tuesday, May 27, a day before NBC aired the first part of its interview, Cole emailed Vines and asked her to respond to seven very specific questions about Snowden and his work, though none touched on whether Snowden raised concerns at the agency.

Vines forwarded the email to officials but didn’t respond to Cole’s queries.

It appears that during the weeklong exchange between officials at the NSA, DOJ, ODNI, and White House, someone went above Cole’s head and reached out to executives at NBC. In an email Vines sent to Hayden on May 28, she said that Cole once again contacted her seeking a response to his inquiries.

“Matthew Cole, the ‘investigative producer’ assigned to NBC’s project, again asked… about the e-mail today,” Vines wrote. “I’m guessing that execs above him have not filled him in.”

Hayden’s reply was redacted, but it appears that NBC was informed about the email, possibly by Hayden. In another email on May 28 to Vines, De, and other senior White House and DOJ officials, Hayden said NBC contacted her and asked “whether our search was just of e-mails to OGC or also to the Compliance Office. Can folks confirm?”

“EVERYTHING email and registry wise was checked,” someone whose name was redacted responded.

That evening, NBC News aired the first part of its interview with Snowden, which included his claims that he raised concerns and complaints about NSA surveillance programs before he made off in May 2013 with thousands of classified documents.

“We should release the Snowden email ASAP,” De wrote in an email late that evening to Ledgett and another person whose name was redacted.

Unlike the Vanity Fair story, the NBC News report generated widespread media interest. Just before midnight on May 28, Vines sent an email to Hayden, De, and others.

How the NSA applied its narrow definition of ‘raising concerns’ to the emails it reviewed isn’t clear.

“Reuters is now pounding the pavement over the email issue,” she wrote. “[Brian] Williams clearly said multiple sources confirmed at least 1 email” that Snowden had sent raising his concerns.

Vines had been hoping the NSA could immediately respond to the claims by releasing the email, thereby undercutting Snowden. Hayden, however, said the administration would not weigh in that night. Hayden added that she saw “relatively little Twitter discussion on the interview.”

By the following morning, the NSA was hastily arranging to have the email released. The agency prepared a rough Q&A for officials there and at the White House and DOJ focusing on questions to which they would have to be prepared to respond. Questions like:

“What is the training and awareness provided to gov’t and contractor employees about reporting activities they perceive to be inconsistent with law or ethics?… Did we receive correspondence from Edward Snowden about his concerns?… How was our search for any correspondence from him conducted?… Is it possible there is correspondence we overlooked, didn’t record?”

Also on the morning of May 29, Litt, in an email sent to high-level officials at the NSA, White House, and DOJ, shared a communication he received from Grannis, the staff director for Feinstein at the Intelligence Committee, about Snowden’s email:

FYI received the attached from David Grannis, which I believe may reflect conversations he had with others as well.

Is there any reason not to make public the one email that NSA/FBI have located between Snowden and NSA people involving a legal question? That email is certainly not what Snowden described in the interview…. The only reason that I can see not to release the email exchange is if people are concerned that there are other emails out there, so I suppose that is a question of how confident are people in their ability to search old records. That shouldn’t be too difficult.

(By the way, Sen. Feinstein spoke last week to [White House Chief of Staff] Denis McDonough and [Obama’s counterterrorism adviser] Lisa Monaco about this very thing, having been tipped off it would be part of the interview. I followed up with NSA OLA [Office of Legislative Affairs] to make sure there was a response in place. I haven’t seen anything yet.)

De appeared to be exasperated.

“OK. I seem to be the only one who thinks we should do something, so I will back off if everyone disagrees,” he replied.

“Raj: This is still an active discussion,” Hayden responded.

De, who has since left the NSA, did not respond to VICE News’ requests for comment.

About three hours before Snowden’s email was publicly released — and while Hayden, De, Litt, and the NSA’s public affairs team continued to debate the merits of the release — a special agent assigned to the NSA’s counterintelligence division sent an email to other counterintelligence officials about additional Snowden emails found within divisions at the NSA Snowden said he had contacted with his concerns.

There were about 30 emails discovered from the security office that Snowden either sent or received. The special agent said many of them were “blast emails” from a redacted source to an email list to which Snowden belonged. There was an email thread asking Snowden to call and discuss an issue he was having with his access card. And there was a thread in which Snowden wrote that his girlfriend, a dancer and acrobat, had been invited to a pole dancing competition in China; presumably, he queried security officials about whether they could attend.

The couple was “counseled against… going,” according to the special agent.

The special agent said there weren’t any emails that Snowden sent or received from the Office of Inspector General. But there were seven emails discovered in the OGC, five of which were “regarding the ability to open certain documents.”

“Strictly a technical trouble shooting email thread,” the special agent wrote.

The confidence that the NSA would soon display publicly that it discovered only one email was not reflective of what was taking place behind the scenes. De was still looking for assurances that it was the only communication from Snowden — but no one could confidently say there weren’t other emails that had been overlooked.

“I would encourage you to work with your staff to give yourself confidence that requests of your folks to check for records are/were sufficiently robust to underpin your personal level of confidence,” someone at the NSA said in an email to De hours before Snowden’s email was released. “l am not in any way suggesting that people did not take the requests seriously — they did, but they did so under time pressure.”

Rogers was informed by an NSA official that the plan, which was based on “dialog with the White House,” called for White House press secretary Jay Carney to read a prepared statement — one that the NSA would send to the White House — and indicate that Snowden’s email would be released later in the day.

Carney was scheduled to give his daily press briefing at 12:30 p.m. Vines said she intended to contact Cole and other journalists and would provide them with the email and the NSA’s statement. Yet even as Carney’s briefing was taking place, NSA officials were still trying to locate additional Snowden correspondence.

In the two years since the email was released, the NSA has not walked back its insistence that Snowden failed to raise concerns internally.

* * *

The NSA did not wait for Snowden’s public comments in the spring of 2014 to start looking through his emails and investigating him. They started shortly after he leaked the documents in 2013.

On June 10, 2013, one day after Snowden revealed that he was the source of the leak in a video interview posted on the Guardian’s website, the NSA sent an email out to its workforce seeking information from employees who’d had contact with Snowden. The email identified Snowden as a “current NSA contractor and former CIA affiliate.”

The NSA’s release of this email to VICE News marks the first official confirmation that Snowden had also worked with the CIA.

In a declaration filed last year in U.S. District Court in response to our FOIA lawsuit, the NSA’s director of Policy and Records, David Sherman, said that the agency collected and searched each and every email Snowden sent.

During a hearing in the case, Justice Department attorney Steve Bressler told U.S. District Court Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson that “there were many searches very carefully conducted by human beings. These were manual ‘eyeball on every email’ searches conducted by people.”

“My staff searched for any records expressing concern about NSA programs by reviewing each individual email in context to see if it was responsive,” Sherman said.

The NSA defined a “concern” as a “worried feeling or state of anxiety about NSA programs rather than bringing up for discussion or consideration a matter of interest or importance.”

How the NSA applied that narrow definition of “raising concerns” to the emails they reviewed isn’t clear.

* * *

Though the NSA publicly expressed confidence it would have found among all of Snowden’s emails ones that more directly involved his concerns with domestic spying, it appears the agency did not actually obtain all of Snowden’s emails. On April 10, 2014, a member of the Media Leaks Task Force asked the chief of the Counterintelligence Division whether “we had a clean capture of all of his work e-mail related to high-side [classified] email — to include any engagement with his Booz chain?”

The response notes that “we have his [Top Secret] NSANet email and his UNCLASSIFIED NSA.gov email,” but that is followed by several redactions.

In June, the chief of staff of the Associate Directorate for Security and Counter Intelligence corrected a document for accuracy to clarify they had “reviewed all of the email and NSANet social media posts authored by Edward Snowden which we have been able to obtain,” seemingly suggesting they were not confident they had obtained them all. Yet several other emails suggest NSA officials were confident they had gotten everything from Snowden’s “final acts in government.”

The same chief of staff also admitted that “it remains possible that unrecorded verbal communication existed between Snowden and one of the offices he cites, but we have not located any individual who remembers any such hypothetical conversations.”

As it would turn out, more communications were located, and they contained important context about Snowden’s correspondence. But a person or people at the agency withheld these details from the media — and initially even from the director of the NSA himself.

* * *

About an hour after Snowden’s email was released, and a few hours after Carney said only one relevant piece of correspondence from Snowden had been located, a member of the Media Leaks Task Force sent an email to a dozen people and offices at the NSA saying the Office of Director of Compliance “reminded us of some other ‘interactions’ with Snowden that may need to be considered.”

The emails found included the one that had been released; a “personal exchange” with an Oversight and Compliance official Snowden had when he “appeared at her desk with concerns about ‘trick questions’ in the test he was taking being the reason why he failed the test”; and the technical email exchanges related to a FISA document template in August 2012 while he served as a systems administrator with Dell.

The task force member said that the group “does not see these as items that show his ‘concerns’… but they do show interaction with the Compliance elements for NSA, albeit administrative in nature.”

Snowden had said in the Vanity Fair piece that he communicated with the oversight and compliance bodies. The NSA had in turn denied this.

About 10 minutes later, a special agent from NSA’s counterintelligence investigations division replied and said, remarkably, that they were unaware that Snowden had a verbal discussion with compliance.

“The in person contact is news to me, but again, not an actual complaint about the law or authorities (just that we use trick questions in our tests),” the special agent wrote.

Forty-five minutes later came another reply, this one from an Army lieutenant colonel who was the chief of the signals intelligence directorate’s strategic communications team. He asked his NSA colleagues to do a bit of soul-searching, and perhaps admit that they should shift their focus away from trying to hold Snowden accountable and instead focus on repairing the NSA’s “brand.”

“The contentions by the fugitive that he had umbrage with programs are not apparent, in any fashion, in these communications,” the lieutenant colonel wrote.

He went on to say that the type of test Snowden had been taking when he asked about legal hierarchies was a standard one given to junior analysts or someone new to working signals intelligence at the National Threat Operations Center (NTOC). This, he argued, proved that Snowden was not working in a senior capacity at the NSA.

“Complaints about fairness/trick questions are something that I saw junior analysts in NTOC (and I had about 8 of them on my team in 20 months) would pose,” the officer wrote. “Nobody that has taken this test several times, or worked on things [redacted] for more than a couple of years would make such complaints.”

After the discovery that Snowden had additional contacts with other divisions within the NSA — which the agency did not inform the media about, and which officials did not disclose to Rogers, the NSA director — a decision was made not to make mention of it in a final Q&A document prepared for the White House.

“There are obviously lots of contacts Snowden had with folks in various organizations of NSA,” wrote the NSA’s deputy associate general counsel for administrative law and ethics in an email later on the afternoon of May 29, 2014. “So long as the Q and A remain fashioned about correspondence regarding ‘his concerns’ — i.e. reporting of violations; questions of lawfulness, etc… then it seems like the planned approach will still be accurate.”

Later that day, Rogers sent an email to several officials and the public affairs office stating that the NSA should be proactive and transparent with the public “as long as we don’t endanger any follow-on legal action.”

“SEN Feinstein adding her thoughts to the public would be of value to the public I believe,” Rogers said.

In a statement Feinstein posted to her website that afternoon, she noted that she was the one who had released the email and that the NSA told her committee it found no other “relevant communications from Snowden… in email or any other form.” That turned out to be untrue.

The email, her statement said, “poses a question about the relative authority of laws and executive orders — it does not register concerns about NSA’s intelligence activities, as was suggested by Snowden in an NBC interview this week.”

Shortly after Snowden’s one email was released, the Washington Post’s Barton Gellman published an interview with Snowden, who responded to the release of the email by saying it was “incomplete.”

It “does not include my correspondence with the Signals Intelligence Directorate’s Office of Compliance, which believed that a classified executive order could take precedence over an act of Congress, contradicting what was just published. It also did not include concerns about how indefensible collection activities — such as breaking into the back-haul communications of major U.S. internet companies — are sometimes concealed under E.O. 12333 to avoid Congressional reporting requirements and regulations,” Snowden said.

Snowden’s statement resulted in a barrage of media inquiries to the Office of Public Affairs and dozens of FOIA requests seeking any additional material showing that he raised concerns. However, the NSA refused to entertain any additional questions, instead providing reporters with a copy of their prepared statement and the sole email.

A day after the email was released, the public affairs office asked the OGC to clear a statement to be sent to the NSA workforce. Grimes, one of the public affairs officials, explained in an email that “several questions” had been submitted to the media leaks internal communications website since Snowden’s NBC News interview had been broadcast two days earlier. The subsequent message to the workforce contained the prepared statement Carney read at the White House briefing along with a statement directed to NSA employees.

“We understand the frustration many must feel,” a draft copy of the statement said. “Please understand we are making every effort to ensure that NSA continues to be transparent with the public while protecting sources and methods and the integrity of the investigation.”

* * *

There were reasons to doubt the completeness of the NSA’s search for Snowden’s emails within an hour of the NSA’s release of Snowden’s one email.

At 1:13 p.m. on the day the email was released, someone in OGC identified a new version of Snowden’s OGC email. By 3 p.m., those responding had found two more details they hadn’t known before, including that the compliance woman had had a face-to-face interaction with Snowden, and that he had provided help to a compliance person having technical issues.

While the efforts on both the document search and the Q&A document continued, on June 3 it took on new urgency. Elizabeth Brooks, the NSA chief of staff, started doing a “review of the thoroughness of the check for material which may represent outreach by Edward Snowden to officials at NSA along the lines of what he claimed.”

Multiple people offered to help, sending email threads from the previous days and weeks. By the end of the day, a senior member of the Media Leaks Task Force apologized to Rogers that he or she hadn’t adequately informed him — and the 31 other people receiving the mail — about Snowden’s interactions.

“I, as the accountable NSA official for Media Disclosures issues, accept responsibility for the representation that the only engagement we have uncovered is a single web platform e-mail engagement with an attorney in the NSA Office of General Counsel,” the person wrote, taking responsibility for leaving NSA leadership “insufficiently informed about this matter,” and promising “to correct for that going forward.”

The email went on to explain what days of searches had discovered were in fact three interactions between Snowden and the Oversight and Compliance Office: the emailed question the training person received and then sent back to OGC; a face-to-face interaction with another training person; and Snowden offering his assistance in troubleshooting a problem with a document template while working for Dell in 2012.

The email includes a passage that describes the process NSA used to assess whether Snowden had raised concerns.

“Through interviews, research and solicitations for information in support of investigative and other requirements we have accumulated a set of data which represents our best, most authoritative capture of encounters initiated by Edward Snowden which may have some bearing on the investigation, media disclosures or his claims,” the apology explained. “We cannot affirm with 100% certainty that this is a complete set of information, that would be impossible to achieve, but it is a body of knowledge upon which we can and have drawn some defendable conclusions.”

The apology then reviews Snowden’s claims, and concludes, in part, that “no examples have been found that rise to the level of his claims.”

The apology is a remarkable example of accountability, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. When the NSA first released Snowden’s email, it suggested his question was simple and the answer straightforward. This was superficially true; does the NSA have to follow the laws passed by Congress — a set of laws generally called the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act — or can a presidential executive order, which for the intelligence community would be Executive Order 12333 (it governs intelligence activities), override that set of laws? The OGC told Snowden that the NSA has to follow the laws passed by Congress.

What failed to be communicated was that the General Counsel’s office and Oversight and Compliance had actually just been collaborating on the subject of Snowden’s question as part of a revision to the training course.

“Two of the OGC attorneys had recently provided the hierarchy of the authorities during the OVSC1800 [USSID 18] course development meetings,” the Oversight and Compliance training woman said a year later while explaining why she sent the question back to OGC to answer. Perhaps for that reason, the two departments engaged in a discussion about who would answer the supposedly simple question; six or seven people got involved in the response.

Then there was the in-person contact with Snowden. As the Oversight and Compliance training woman described in an email written a year later, he “appeared at the side of my desk in the Oversight and Compliance training area… shortly after lunch time.” Snowden did not introduce himself, but “seemed upset and proceeded to say that he had tried to take” the basic course introducing Section 702 “and that he had failed. He then commented that he felt we had trick questions throughout the course content that made him fail.”

Once she gave him “canned answers” to his questions, “he seemed to have calmed down” but said “he still thought the questions tricked the students.”

That may well have been the woman’s perception of the exchange, but it is unlikely that Snowden, who six weeks later would walk out of the NSA with thumb drives full of NSA secrets, was agonizing over failing an open-book test.

The Oversight and Compliance training woman now said the exchange happened “during the timeframe between 5-12 April 2013.” That means the exchange occurred within a week — and possibly on one of the same days as — the discussions about how to respond to Snowden’s emailed question to OGC. The training woman said Snowden did not introduce himself, which means she wouldn’t have known he was the same person whose question she had sent back to OGC; nothing in her explanation reveals how she later came to understand it had been Snowden.

There’s evidence the NSA’s training materials and courses at the time had significant errors. A revised Inspector General report on Section 702 of FISA, reissued just days before Snowden returned to Maryland for training on the program in 2013, found that the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) posted on the NSA’s internal website, purportedly telling analysts how to operate under the FISA Amendments Act passed in 2008, actually referenced a temporary law passed a year earlier called the Protect America Act.

“It is unclear whether some of the guidance is current,” the report stated, “because it refers only to the PAA,” a law that had expired years before. A key difference between the two laws pertains to whether the NSA can wiretap an American overseas under Executive Order 12333 with approval from the attorney general rather than from a judge in a FISA Court.

If the SOPs remained on the website when Snowden was training, it would have presented a clear case in which NSA guidance permitted actions under E.O. 12333 that were no longer permitted under the law that had been passed in 2008. It would have seemed as though the NSA were flouting the law when spying on American citizens.

Similarly, a key FISA Amendments Act training course didn’t explain “the reasonable belief standard,” which refers to how certain an analyst must be that a target was not an American or a foreigner in the US — a key theme of Snowden’s disclosures. While some work on both these problems had clearly been completed between the time of the report’s initial release and its reissue just days before Snowden showed up in Maryland, both these findings remained open and had been assigned revised target completion dates in the reissued report, suggesting the IG had not yet confirmed the problems had been fixed.

The issue of whether the presidential Executive Order that the Intelligence Community uses to authorize its overseas activities, E.O. 12333, can trump the law Congress passed in 1978 to impose limits on spying, has been a simmering issue since DOJ lawyer John Yoo secretly claimed in 2001 that FISA’s limits on Executive Branch spying might be an unconstitutional infringement on the president’s authority. It has been a public issue since 2006, when the DOJ revealed a theory that the war against al-Qaeda meant the president could override the law passed by Congress, and was a key issue in passage of the FISA Amendments Act in 2008.

It was also central to one of Snowden’s most inflammatory revelations, documents showing that the NSA was hacking Google overseas, effectively giving itself a way to bypass FISA and access domestically collected data directly. And it was an issue Feinstein and Senator Mark Udall raised in a confirmation hearing months before Feinstein would advocate an assertive response to Snowden’s claims in 2014.

* * *

The video of Snowden released by the Guardian on June 9, 2013 may very well have been what triggered the woman from Oversight and Compliance to recognize that it had been Snowden who approached her at the NSA. The next morning, when she “realized I had contact with him,” the first thing she did was try to “pull his training record, but it had already been pulled from the system.” She “reported the [face-to-face] contact to my management and considered the issue closed.”

If she reported it in writing, that document was not released to VICE News. Instead, the documents we received show that the face-to-face exchange with Snowden wasn’t written up until April 9, 2014, a year after the exchange and after teasers from the Vanity Fair article revealed Snowden was claiming he “contacted NSA oversight and compliance bodies directly via email and that I specifically expressed concerns about their suspect interpretation of the law.”

In the absence of a response from the NSA or Snowden, it is impossible to know what to make of this contact. One person who would speak on the record, however, is former NSA official turned whistleblower Thomas Drake. We asked him how the compliance department functioned, though we did not reveal to Drake details of this report. Drake told us, “These are positions that are designed to protect the institution from bad news, even internally. So, you know, ‘We’ll turn bad news into good news.’”

One thing that is clear, however, is that the apology laying all these details out, written after several days of fact checking at the NSA and document review in June 2014, leaves out at least one key detail — that the OGC email and the face-to-face communication could have happened the same day, making it far more likely they should be treated as parts of the same exchange. More significantly, the apology claims that “in response to the June 2013 Agency All… she provided in writing her account of these engagements.” If the timestamps on documents provided to VICE News are correct (something that the NSA has admitted is a problem with this FOIA response), she actually provided her side of at least the OGC contact even before the Agency All email. But there is no record she provided her written account, to either of these exchanges, until a year after the event, a detail — if true — that Rogers should have known.

* * *

Snowden noted in his testimony to European Parliament that there was no safe avenue for contractors like him to raise concerns.

“U.S. whistleblower reform laws were passed as recently as 2012, with the U.S. Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act, but they specifically chose to exclude intelligence agencies from being covered by the statute,” Snowden said. “President Obama also reformed a key executive whistleblower regulation with his 2012 Presidential Policy Directive 19, but it exempted Intelligence Community contractors such as myself. The result was that individuals like me were left with no proper channels.”

The NSA’s director at the time Snowden left the agency, Gen. Keith Alexander, seemingly did not know whether contractors were covered by whistleblower protection laws. He emailed Ledgett four days after Snowden testified before European Parliament on March 11, 2014.

“Rick, I believe there is also a Whistleblower methodology for contractors. Do we have that?” Alexander wrote.

“Sir, it’s not the recently enacted Whistleblower Protection Act but there are previous laws that protect contractors. Cc’ing Raj [De, the NSA general counsel], and [redacted] who can provide that info,” Ledgett responded.

A person at the NSA whose name was redacted weighed in on another email, telling Alexander:

The Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act of 1998 and Presidential Policy Directive PPD-19 provide a mechanism for both employees and contractors to report alleged wrongdoing. Whistleblowers can report matters of “urgent concern” to the NSA IG [Inspector General, a government organization’s internal watchdog] and DoD IG. Whistleblowers, to include contractors, can report matters of “urgent concern” to the intelligence committees after notifying the NSA IG or DoD IG of the intent to do so and obtaining direction from the IG on how to contact the Intelligence Committees. The Whistleblower statute provides an avenue to report concerns related to classified matters without improperly disclosing classified information.

The documents released to VICE News revealed that the Q&A the NSA prepared for the White House just before the release of the lone Snowden email went through many rounds of editing and fact-checking, rounds that demonstrated the limits of what the NSA would claim about its own oversight, Snowden’s claimed efforts to raise concerns, and whistleblowing.

An early draft aspired to determine “how many cases [of a contractor’s concerns] have been brought to the attention of Agency officials, and how those cases were closed out,” but the final document states only that “NSA OIG keeps a record of all inquiries and actions taken.”

Early on, the Q&A noted that “technically speaking all reported activity that is found to be a violation of law, directive, or policy requires some corrective action.” By the final version, that clause was changed to read, “Activity that is found to be a violation of law, directive, or policy is thoroughly reviewed to determine corrective action.”

The changes in the Q&A document also reflect the evolving understanding of Snowden’s complaints. On June 3, not long before the apology to Rogers, the security chief of staff changed the characterization of what the email search had found “for purposes of accuracy” to state they had reviewed all of Snowden’s emails “which we have been able to obtain.”

NSA tried to make the case that Snowden should have known where to voice his concerns thanks to (sometimes mandatory) training that emphasized limits to the NSA’s authority, and how to report any violations of those limits. “These specific training courses discuss the limitations of SIGINT authorities and mission operations to include reminders and guidance about who to contact with questions about scope of authorities, and who to contact if there are known or even potential compliance concerns,” the Q&A document said.

The Q&A cited a basic training course called “NSA/CSS Intelligence Oversight Training” as the place where most people learn how to report a concern. The document claims, “Most contractors are required to take this course,” and asserts Snowden was a category of contractor who would have been required to complete it. But it stops short of asserting that Snowden actually did so.

The editing process of the Q&A document also indicates that the other means by which Snowden might have learned he could make protected complaints — via the IG himself — were not crystal clear.

The initial drafts of the document overstated the degree to which the NSA’s IG invited whistleblowers to report legal violations. It started by claiming, “The NSA OIG [Office of Inspector General] also provides briefings to various NSA training classes, including the new hire orientation class.” But on June 3, 2014, the IG’s Executive Officer admitted, “Technically we are not quite briefing [that class] yet… still trying to get OIG on schedule.”

Similarly, it claimed, “The OIG also issues agency-all messages covering policies and avenues for reporting suspected mismanagement and violations of law, policy, and regulations.” But on June 4, the counsel to the Inspector General noted the agency-all messages “aren’t as focused as the two [post-Snowden] ones you mention, and we might need to massage the words a little.”

As the finished Q&A document makes clear, before Snowden’s leaks, the most regular notice sent to all employees from the IG pertained only to reporting “waste, fraud, mismanagement of Agency resources, and abuse of authority.” After the leaks, in the spring of 2014, the IG sent out a notice stating that NSA/CSS Policy 1-60 “requires that NSA/CSS personnel report to the OIG possible violations of law, rules, or regulations,” as well as things like mismanagement. It also cites the Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act (ICWPA).

The Q&A document goes on to describe other reporting mechanisms, and includes one, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Office, that was created in August 2013 — as a response to the Snowden leaks.

Watch State of Surveillance, the VICE on HBO episode featuring Edward Snowden:

Thus, while the Q&A document does provide a list of ways in which legal issues might be raised within the agency, it’s also a list of resources put in place in response to Snowden’s leaks, an indication that the resources available to Snowden may have been inadequate.

And it’s still not clear these policies even apply to contractors. Congress is only now debating, in the Intelligence Authorization for next year, requiring the Intelligence Community Inspector General to report “the number of known or suspected reprisals made against covered contractor employees during the five-year period preceding the date of the report,” and to evaluate “the usefulness of establishing in law a prohibition on reprisals against covered contractor employees as a means of encouraging such contractors to make protected disclosures.”

Even though Litt claimed to be trying to provide more protections for contractors, he had not heard of this provision when asked during our interview. Instead, he explained why the government can’t protect contractor whistleblowers.

“We are constrained what we can do with contractors,” he said. “We don’t have the ability… to modify a contractor’s employment relationship with his employer.”

* * *

Last weekend, former Attorney General Eric Holder said Snowden’s leaks, while illegal, were a public service because they sparked debate about the legality of surveillance programs and resulted in changes.

Sen. Ron Wyden, one of the Democratic members of the Senate Intelligence Committee, agreed.

“Senator Wyden certainly believes that protections for intelligence agency whistleblowers need to be much stronger, to prevent retaliation and encourage reporting of serious systemic problems,” said Keith Chu, a spokesperson for Wyden. “However, in the case of mass surveillance, agency leaders, inspectors general, and the relevant oversight committees were all aware that mass surveillance was happening, but the problem was not fixed until it became public.”

The NSA declined to respond to a series of questions VICE News sent the agency. Instead, on the afternoon of June 3, NSA spokesperson Michael Halbig provided us with comments about avenues whistleblowers like Snowden could take to raise concerns about waste, fraud, and abuse.

Those comments closely match the language in the Q&A document prepared for the White House in 2014.

Perhaps the NSA was hoping to get ahead of VICE News’ report. At 11:40 p.m. ET on Friday, June 3, Vines, the NSA spokesperson who clashed with NBC’s Matthew Cole and was critical of other journalists’ coverage of Snowden, emailed VICE News to say that the documents turned over to us after two years of litigation had been publicly posted to the agency’s website.

It was an extraordinarily unusual move for an organization that by its nature shuns transparency. It also had the potential to critically limit the scope of our story.

The NSA posted the documents hours after we contacted the agency for comment.

An NSA cover letter accompanying the release on the website said, “The documents illustrate that, as the Agency reported in May 2014, NSA conducted a thorough search of e-mail and has no records of any e-mail from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden to Agency officials raising concerns about NSA programs.”

The letter went on to say: “[T]he Agency has no record that he submitted complaints to senior NSA leadership — including the NSA Director, Deputy Director, and Executive Director.”

It’s a denial of claims Snowden has never made.

Note: Marcy Wheeler’s blog, emptywheel.net, has received funding from the Freedom of the Press Foundation, of which Edward Snowden is a board member.