Content Warnings: This review discusses depictions of alcohol abuse and suicide.

Spoiler Warnings: This review discusses some character arcs and discusses some specific story moments.

Back in 2012, game designer Warren Spector said that, given the budget and the time and the ability, his dream game would be one fully simulated city block. Then-critic and now-developer Jim Rossignol wrote a speculative piece about it, asking what it would truly mean to take that idea seriously. What would the boundaries be? How would the plot move? Are games like Dishonored or Gone Home already tapping into this design space?

Videos by VICE

Seven years later we have Disco Elysium, a top-down roleplaying game that takes place entirely in an area slightly larger than a city block. It’s the One City Block RPG. Substituting a depth of conversation and interaction with the world for Spector’s focus on simulation, Disco Elysium is based around the fundamental linkages between things in the world. People have bosses, bosses have ideologies, ideologies have material expressions in the world, and people live in those expressions. The circle of political life goes around and around.

Crucially, Disco Elysium doesn’t just posit cause and effect and go from there. It takes this space and its fundamental connections and takes them to the most extreme place that it can: One where everything matters. What you’re holding in your hand during a conversation matters. What item you picked up 15 hours ago matters. What you said in a conversation at the very beginning of the game, the skill points you put in during character creation, and your choice of bedtime. All of those things compound on each other and worm their way, intricately, into conversations and small moments and the big plot points of the game. There is nothing so small that it does not matter. The city block shifts and moves beneath your eyes and your feet and your fingertips. As the cop show once said, all the pieces matter.

And Disco Elysium is a cop game. There’s a man hanging by the neck in a courtyard around the back of a hostel, and someone called it in a week ago. The player character, Harry DuBois, showed up to take care of it. Except he failed, or decided not to, or couldn’t get a handle on it. For reasons unknown, he drank and drugged himself into a stupor so deep and annihilative that he wiped his entire memory. The game justifies itself with mystery and recovery: Recovering Harry’s memory, recovering the case, and just generally getting his shit together. The work of it is organizing all of these in time and space. Can you solve the case of who killed the hanging man and why? Can you recover your missing badge and gun? Can you return to your status as a cop, or do you even want to? These questions sit on the surface of the game, but they also plumb into the depths of DuBois’s mind. A conversation might take you through dialogue with a gardener, Harry’s conceptualization of abstract ideas in the world (the skill Conceptualization), and his partner Kim Kitsuragi. Harry converses with them all as if they’re equivalent entities in the world who can help him out. Inside of him, his skills are alien advisors. Outside, he’s alienated by the society and systems that he can’t remember but which are nevertheless still in conversation with those internal aliens.

***

At the beginning of the game, before he can remember his own name, Harry decides that he wants to perform karaoke of a song he’d been jamming to during the bender that led up his complete loss of memory. It’s a melancholy track, “The Smallest Church in Saint-Saëns,” that tells a short and oblique story about what once existed and has been lost. As the song says, “I have been so glad here / looking forward to the past here.”

Performing karaoke was a quest in my log, and it took me a while to find the appropriate musical track for perfect accompaniment of Harry’s half-remembered anthem to sadness. I had to talk to people and track it down and really think about where the hell I might find a music album in the half-ruined, post-war situation that is the city of Revachol.

And when I found it, I performed it, and there in the middle of Disco Elysium I knew that something special was going on. I’d built this experience up in my head, and here Harry was on-stage, and I realized that I had a single check in front of me. I needed to click the button that said I would attempt to perform this act of performance. But I hadn’t invested anything in the skills that might help the performance. I failed the check, and Harry let out this beautiful wailing rendition of the song, a desperate statistical failure that everyone in the game reports as bad. Harry did it, and he was fulfilled, and everyone hated it.

Later, Harry’s new partner Ken said it was a decent performance.

A few minutes before the performance, a tween was screaming slurs at me. This is the same kid that Austin Walker mentioned in the episode of Waypoint Radio from a few days ago, and he’s right to pick Cuno out as emblematic of something that Disco Elysium is doing. Martenaise, the neighborhood of Revachol that the game takes place in, is a rough place to live, full of systemic poverty and organized crime. It has been functionally abandoned by the occupational government that rules the former world capital from afar. Everyone you can speak to in the game knows they are living in the wake of capital-h History: A lifetime ago, Revachol experienced a communist revolution, and the capitalist powers of the world conspired to destroy it. They won, and we’re all here in the aftermath of that, in an extremely deregulated situation where the bones of the Old Old World are still being picked clean, block by block, street by street, by the free market.

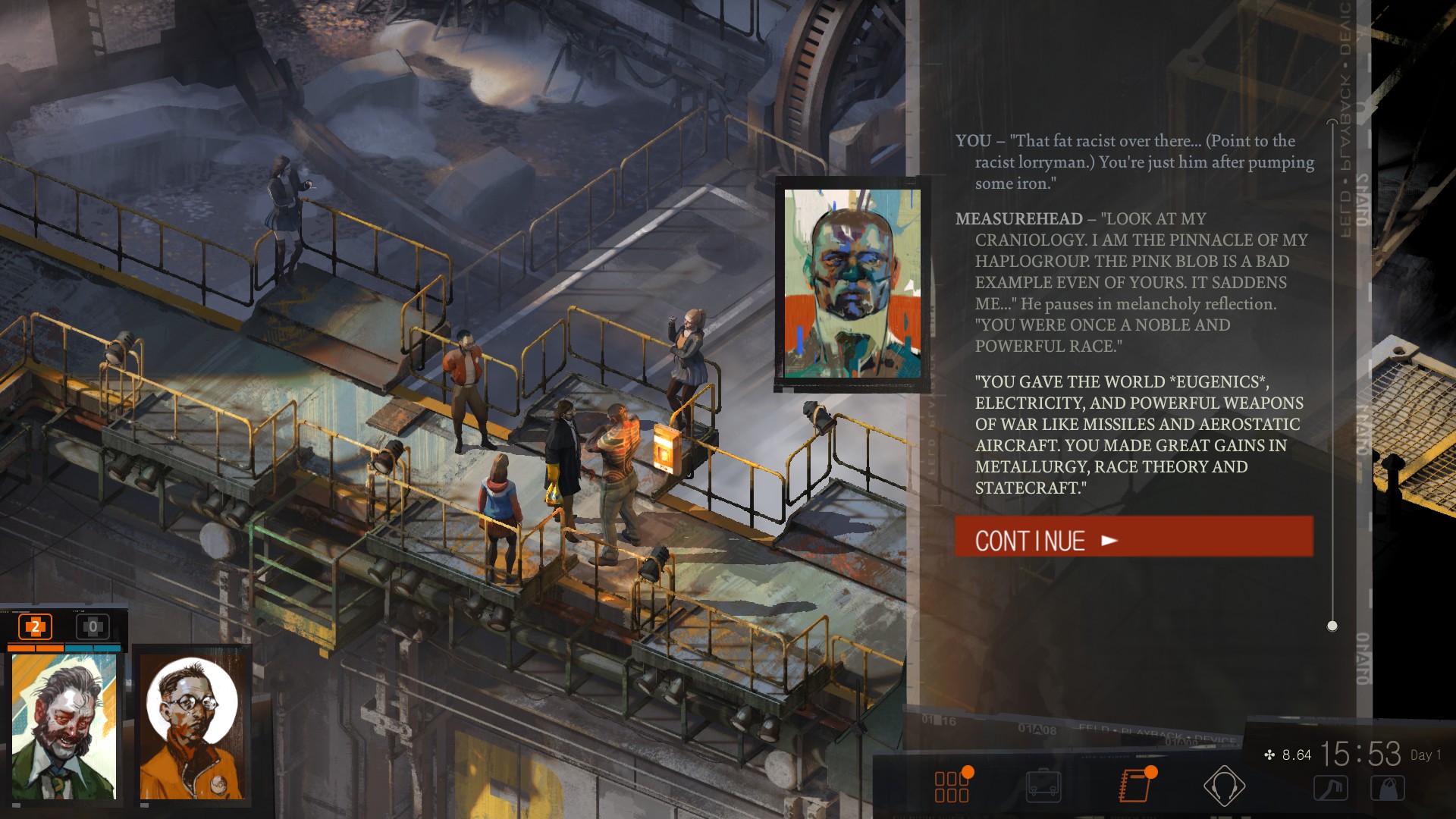

And that’s made manifest in a teen named Cuno and his “friend” Cunoesse hollering slurs at Harry and Kim. We’re meant to see it in the racist mug collection of a character who literally has “cryptofascist” appended to his name, in the racial science advocate Measurehead, in the racist delivery truck driver, in the anti-communist ramblings of the old guard soldier, and even in the extensive nationalist or racist statements Harry can make about this fictional world. All of these characters are living in this deep world with an extensive history that has been developed by designer and lead writer Robert Kurvitz for at least 12 years. All of these people, and Harry’s responses to them, are about showing us how everyone swims in ideology. Our beliefs about the world, and how we make decisions based on those beliefs and shape the world around them, are being simulated here. There’s a wry smile, a kind of “dirtbag left” sensibility, and a delivery that Kurvitz characterizes as a kind of hollow laughter.

On one hand, it is an enviable thing to try to cram this deeply written world full of real-life ideology and giving players the capability to navigate these things and make choices within them. The designers of Disco Elysium clearly want to provide players with the largest possible space to experiment and play in, and they try to set the boundaries of the game as wide as the real world itself. I can play this game as a nationalist and explicitly racist Revacholian hardass cop if I want to. Or I can play it as a radicalized resurrectionary Communist. Or I could do what I really did, which was as a Moralist “the best position is the center” chump of the state.

The design is intentional, and it works, but the reality is that it also sucks complete shit to engage with a character who literally just spews 19th century race science at the player character in a game that trains you to look for something neat or special behind every dialogue choice or option. The world is full of wonder and strangeness and people with depth and detail, but the structure of this world is so similar to our own that the ideological chatter basically looks like any given Twitter hashtag with the nouns replaced.

***

Late in the game I learned that Harry DuBois also went by the moniker Tequila Sunset. As the name suggests, he was an alcoholic and a complicated person. He was good at solving cases, or at least better than most, and he seems to have worked and been generally honest. But he was also a machine falling apart at the rivets, and abandoning his mind seemed like the best option for him at some point. I never found out why. Every time it came up, I took Harry in another direction, deciding that he didn’t want to know. Similarly, I never found my gun, something that would have come in handy at several moments. But I wasn’t sure that Harry wanted to be a cop anymore. I wasn’t sure he wanted to exist, and I got an early game over by trying to gain control of a situation by borrowing a gun and putting it in my mouth. It didn’t work.

***

If you asked me for a one-sentence description of Disco Elysium, I’d give you this: It is Planescape: Torment, but more. 20 years ago, Torment began from the basic assumption that the play of a game could be tooling around in its story, and it ran with it. It’s still regarded as one of the best-written games of all time for that reason. It builds itself around a formative twist, but that twist isn’t what keeps it in the heads of so many of us now. Like Fallout and multiple decades of tabletop roleplaying before it, it saw the mechanical layer of skills and ability scores as creating a platform on which interesting narrative situations could be built. What if you were so smart you could think your way around the problem of the central narrative? What if you were wise enough to stump the concept of mortality itself in a metaphysical argument?

So much of what remains engaging about Torment has less to do with the big narrative moves and more to do with the feeling of “oh shit, they thought of that?!” when strange things come up. This is fundamentally what makes Disco Elysium work so well, too. Rather than being something explosive and new and revolutionary, this whole operation is an intensification, an output of something that’s been powering along for more than two decades. Disco Elysium is a game where every edge case has been thought through to the best of the dev’s ability. Again, everything matters, even the hair that stands up on the back of your neck and the feeling that you get when you look into the hanged man’s eyes.

***

I spent enough points on a skill called Inland Empire early on that Harry could project himself through the veil of reality. When the skill was evoked, it took me on a journey like that of its namesake, through the haunted corridors we can’t bear in our day-to-day. I looked into the eyes of the dead man, and he spoke. We had a heart to heart. He told me that communism killed him, and I didn’t believe it. And then Lieutenant Kitsuragi asked me to snap out of it and return to the autopsy. I can still feel the precise emotion that made me smile when that little path opened itself up in the conversation. When the game works, it really does feel like magic.

***

Eventually the slurs and weird racist routes that the game was so willing to let me go down dried up. I never selected them, deciding to play Harry as a bad cop but a decent person, and eventually the passive skill checks from Harry’s internal Drama and Rhetoric and Electrochemistry calmed down. Part of Disco Elysium’s claim to innovation is having each of its 20 skills getting checked constantly in the background of conversations or in response to Harry’s situation. They’re companions, in a way, and their intrusive expertise always seemed to be at the beck and call of ideological flurry. The interesting part about Disco Elysium, of course, is that I have no idea if it was my play style warping the game around me or the game providing less opportunities for things to happen outside my ideological “lane” at this point. And this mystery, I gather, is the point.

If the skills are a kind of companion, I’d be remiss if I didn’t say something of substance about Lieutenant Kim Kitsuragi, the man who came to wrangle both the case and Harry into shape. In another one of those edge-case covering scenarios, I imagine that there are a lot of ways the relationship between Harry and Kim can go, but for me it was all professional boosterism. Steel sharpens steel, or whatever the Crossfit crowd says, and Kim’s attention to analytic detail and my version of Harry’s skill at Visual Calculus, a CSI-style ability to imagine what happened in a particular location, allowed us to solve several side missions and get a decent picture at what happened with the hanged man. We had some victories, I guess, and Kim is written in such a way that I came to feel that I really knew him and why he cared about all of this in the end. He just wants to take good notes and leave the world a little better than he found it. And to drive fast cars.

***

I didn’t really solve everything. At the end of things, Harry was met by the special taskforce that he commanded before this whole thing got started, and they asked him whether he had gotten himself together. Police car wrecked. Badge recovered, thankfully. No gun. No idea what drove him to snap his life in half with a bottle. A hat that was given to him by a little girl whose mother finally let her go back to school. The solemn satisfaction that he kept a tween from getting access to amphetamines, and the sick feeling that he didn’t really end up helping.

With all of that compiled alongside all of the other half-victories and definite failures that the developers worked hard to make me comfortable with, Harry DuBois decided to be a cop. The stick bug was still rumbling around in his head, in my head, and hell, it looked like Kim might switch stations and come along back with me.

Small victories, and a Harry who at least knows who he is, if not how he wants to be in the world. That’s what the game provided for me. With an ending like that, and the experiences I had peppered in the middle, I feel like the right amount of melancholy and the exact dash of bleakness happened in Disco Elysium. I fumbled my way into Harry making peace with himself and the world around him, and it seemed like a win. But no matter how much I am enchanted with the form and the accomplishment, I can’t help but think about how little the racism against Lieutenant Kitsuragi or the knowing, joking evocation of race science ended up mattering. In the final calculus, it was something I had to sit through and sift through to get to an experience that had a soul to it. And I’m afraid that the only way it would have mattered is if I had committed to it and decided to be that nationalist, racist Harry DuBois. It would have only truly given flavor to the world if I wanted to pursue that particular flavor. And I’m unsure if I think that would have made the game more interesting, or better, or even worth engaging with. Contrary to its obvious intention, it seems like it would have only served to rob this vibrant world of nuance and power, reducing everything down to pre-existing categories and prejudices. Playing Harry as a self-justifying racist machine wouldn’t bring me any joy. The game would have meant less.

***

When Spector or Rossignol talked about the One City Block RPG, what they were really after was a certain set of dependencies. Everything could rely on everything else, and banging on a wall might disturb a neighbor who opens a window, letting a cat out and giving the kid three doors down a new pet for the evening. The city block is about depth and narrative and the idea that things can be attached in time and space to create powerful experiences in games. At base, Disco Elysium is this goal accomplished by other means, this towering object of labor and legitimate skill which is going to be the mark from which we measure these kinds of games in the future. And I’m left thinking about what will get picked up here and recognized as the contribution the game made to the world. Will it be the wonder and joy of small moments and big narrative context? Or will it be the hollow laughter at the ideological human, the person who believes too much and often without thought? I hope for the former. I fear for the latter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: YouTube/Lacry -

Screenshot: YouTube/Nintendo of America -

Screenshot: Untold Tales -

Screenshot: Electronic Arts