There is no concept more American than “free will”—the idea that we’re all gifted (probably by God) with the power to choose a path of success or destruction and bear responsibility for the resulting consequences. It’s the whole reason we “punish” people for committing crimes. The idea is so ubiquitous that most people have never even pondered an alternative.

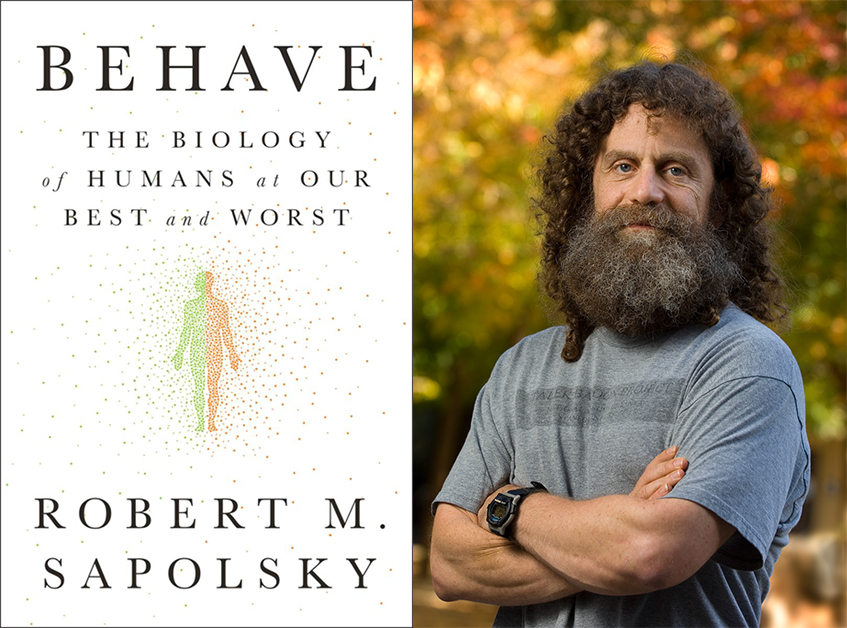

Neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky sees things differently. He’s opposed to the concept of “free will.” Instead, he believes that our behavior is made up of a complex and chaotic soup of so many factors that it’s downright silly to think there’s a singular, autonomous “you” calling the shots. He breaks all of this down in his new book, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. The tome is a buffet of neurology, philosophy, politics, evolutionary science, anthropology, history, and genetics. At times, its exhaustive in the number of variables considered when looking at human behavior, but that’s Sapolsky’s whole point: The decisions we make are a result of “prenatal environment, genes, and hormones, whether [our] parents were authoritative or egalitarian, whether [we] witnessed violence in childhood, when [we] had breakfast…”

Videos by VICE

Like David Eagleman’s Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain, or Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Sapolsky’s Behave reveals the mechanisms going on behind the scenes of our consciousness. I talked with Stanford’s resident neurobiologist and primatologist to discuss his new book. We touched on free will, the nature of existence, and how humans learned that epileptics don’t deserve to be burned alive.

VICE: Tell me about your new book.

Dr. Robert Sapolsky: The basic theme is that we are biological creatures, which shouldn’t be earth-shattering. And thus all of our behavior is a product of our biology, which also shouldn’t be earth-shattering—even though it’s news to some people.

If we want to make sense of our behavior—all the best, worst, and everything in between—we’re not going to get anywhere if we think it can all be explained with one thing, whether it’s one part of the brain, one childhood experience, one hormone, one gene, or anything. Instead, a behavior is the outcome of everything from neurobiology one second before the action, to evolutionary pressure dating back millions of years.

Your book expresses some pretty novel ideas about free will and the criminal justice system.

I do not believe in the existence of free will, but it’s incredibly difficult to imagine a world in which people have accepted that reality, particularly when it comes to the criminal justice system. Ultimately, words like “punishment,” “justice,” “free will,” “evil,” “the soul,” are utterly irrelevant and scientifically obsolete in terms of understanding our behavior. It’s insanely difficult for people to accept the extent to which we are biological organisms without agency.

This matters more in some areas than in others, right?

If someone compliments you on your hairstyle, and you want to take credit for it instead of outlining the millions of years of force that drove you to choose that style over another, that’s not a big deal. But where we have to get away from absurd, outdated ideas about our own agency and think through the biology are the realms of behavior that we judge harshly: when sitting on a jury, when evaluating a student in a classroom, when trying to make sense of a loved one’s behavior… That’s where we need to acknowledge that it’s just biology every step of the way.

You open the book confessing that you have a fantasy of enacting justice against Hitler, even though that fantasy contradicts your scientific perspective concerning justice against evil. It sounds like you’re suggesting that we should have empathy for those who commit the worst crimes, even if it goes against our impulses.

The analogy I always use, which is so difficult for people to swallow when it comes to the criminal justice system, is that if a car has faulty brakes, you fix the breaks. If the brakes are not fixable, you put the car in the garage for the rest of the time, and your primary responsibility is to make sure this car with the faulty brakes doesn’t hurt anybody. But nobody is saying you’re punishing the car. Nobody is accusing your car of having a moral failing. Somehow, we have to reach that mindset.

Most people would react with hostility to this way of thinking, since it is so different from how we look at things today.

This shift in thinking sounds inconceivable to people in most realms, but we have done it in the past. Five hundred years ago, if you were a smart, thoughtful, reflective, even bleeding-heart liberal, you still believed that anyone who had a seizure was demon-possessed, and therefore you should burn them at the stake. It took us those 500 years to develop a mechanized view of epilepsy, thinking of it like a car with broken brakes, realizing, “Oh, it’s not this person’s fault, it’s not a problem with their soul, they didn’t have sex with Satan, they have little feedback loops in their brain. Since it’s taken Western civilization 500 years to get there with seizures, who knows how long it will take us to do it in the more subtle realms of abnormal behavior that we currently explain with theology.

If we aren’t responsible for our bad behavior, then we’re also not responsible for our good behavior, right? Would that mean that all success in life is by chance?

That one’s the sleeper in the equation. As difficult as it is for us to be comfortable with a mechanized view of our worst behavior, it’s much harder for people to accept that it’s all biology when it comes to our good behavior as well. It’s a less pressing problem compared to issues of mass incarceration. But yes, we need to acknowledge how much sheer damn luck of biology has gifted some of us with things that others haven’t.

Abolishing the notion of free will also contradicts the Abrahamic theology of God’s relationship with man—and perhaps the existence of God altogether.

It is in passing. As a strident atheist, I have no objection to that being the case. But it is also an attack on something else: The idea that we are more than our brains, that there’s something inside of us, a being that is in our brain but not of our brain, a “me” that is more than just biology. And that is as grounded in reality as alchemy or astrology. Some people tie that idea into a religious framework, but even outside of religion, your average person believes that there’s something more to themselves than just chemistry or biology.

So your theory goes beyond religion or the the soul. You are attacking our fundamental understanding of human existence.

Every other year I teach a classroom version of the ideas in this book. There will be around 500 or 600 people in there, and so it’s statistically guaranteed that I’ll have five or six students having a religious crisis over all of this, and three or four others having some kind of existential crisis. It’s very unsettling stuff. We like our individuality, we like the mysteriousness of us, the essentialism of us, and it can be alarming to see the biological gears turning underneath.

Can this understanding help us predict behavior?

There’s not a whole lot of science that can look at a group of people with damage to their prefrontal cortex and say “this one is going to be a serial murderer, and that one is going to belch loudly at a eulogy and not understand why it’s socially inappropriate.” But when you look at the pace of what we’re learning about the origins of human behavior, in time the notion of that little being that sits inside our brains making decisions is going to get crowded into smaller and smaller places.

One non-biological factor that you believe influences our behavior is culture. Or does culture impact the biology of our brains, too?

It does in enormous ways. If you were raised in hard-assed individualist United States versus East Asia’s collectivist culture, that may produce different ideas about cooperation and how you interact with a crowd. Take someone who was raised in an urban environment of more than 100,000 people, versus someone who was raised in a rural area. On average, those raised in an urban environment have a larger amygdala [a region of the brain involved with fear and anxiety]. So in that way, culture can physically change the brain.

What if you’re from the rural South?

There’s a famous study where student volunteers thought they were involved in a study surrounding their math abilities, but the experiment actually occurred outside in the hallway. Some beefy guy walking the opposite way bumps into a student as he walks past, then says, “Watch it, asshole,” before marching away. When the student comes in to take the math test, the researchers take their blood pressure, check their hormones. And if you’re from the American South, your blood pressure will be higher, and you’ll be more stressed out. This impacts your judgement and how you respond to a given situation.

This is because, by best evidence, the American South was settled by herders and pastoralists from northern England and Scotland, who had a culture of honor. Centuries later, there’s still a residue of that. So this makes culture not such an intangible factor of brain development and behavior. Within minutes of birth, this kind of training starts.

Can understanding these factors get us closer to having free will?

If you were brought up in a culture that values reflection, introspection, and critical thinking about your own thinking, one that questions whether you are being rational or if you are rationalizing, then you’re training your cortex to be a better assessor of what’s going on in your limbic system [a region of the brain that influences behavior, but isn’t engaged in conscious thought]. When you’re being asked to think about the meaning of your intuitions before you act on them, maybe along the way you decide your intuitions are destructive or make no sense at all. And then you don’t act on them.

Follow Josiah Hesse on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Illustration by Reesa -

Screenshot: ROH -

Screenshots: Facebook/Jon St John, Sega -

NDZ/Star Max/GC Images/Getty Images