Few artists have done self-effacement with as much charm as Pete Shelley. Add to that the Buzzcocks singer’s unerring gift for melody, his arch delivery and his witty, often innuendo-driven lyrics, and you have an artist so singularly talented that there was always a suspicion he was too good for punk. The irrepressible pop sensibility, the bashfulness, the universal sense that Shelley was nice… these things have stopped him from being admitted to the punk club of untouchables alongside Johnny Rotten, Iggy Pop, Joe Strummer et al (Buzzcocks have scandalously yet to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame either).

The penny dropped with a few obituary writers on Friday though, as they took a look back over his distinguished career. The “Spiral Scratch” EP is now considered indie year zero, and as lead singer, guitarist and chief songwriter in the Buzzcocks after bandmate Howard Devoto left, he inspired one of the great single runs between 1977 and 1979 (all captured on the blistering Singles Going Steady compilation). He and Devoto organised the Sex Pistols’ legendary Manchester Free Trade Hall gig and gave Joy Division their earliest breaks. His claim to immortality looks like an open-and-shut-case: Pete Shelley was a musical genius hiding in plain sight.

Videos by VICE

For many the story more or less ends there. His solo career gets a cursory mention before the Buzzcocks reformation in 1989 where everyone kisses and makes up and the band tour happily ever after. But to dismiss Shelley’s solo albums is to do him – and them – a great disservice. I’d argue that he produced work on a par with Buzzcocks in their purple patch, and that he was extraordinarily unlucky not to have similar success with his esteemable 80’s electro output. A reevaluation is long overdue.

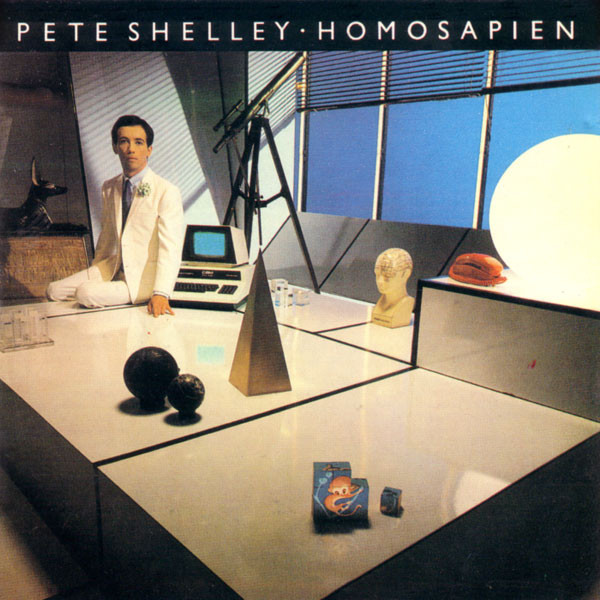

His first solo single, “Homosapien”, became a club banger when it was released in 1981, but it should have gone to the upper reaches of the charts. It’s a catchy, insistent gem that still sounds vital now (and still gets played in clubs). Unfortunately for Shelley, a sharp-eared BBC employee picked up on the “homo superior / in my interior” line and Auntie slapped a ban on it for “explicit” content. Explicit seems excessive viewed from 2018, though it was Shelley’s first overt reference to his sexuality after covertly alluding to it all those times on Top of the Pops during the late 70s. “Homosapien” is a cybersexy nod to both Bowie and Gary Numan, but faintly holding the record together is a 12-string guitar played by Shelley that adds depth and bridges his new direction with what he became known for.

If the sudden change in direction surprised fans, Shelley had actually been interested in electronics all along: he recorded Sky Yen, an oddly enjoyable experimental noise album full of diving drones in 1974, and released it on his own label Groovy Records years later in 1980. The original recording preceded Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music by a year and was influenced by Tangerine Dream, while his first musical love was Can (he apparently wrote the liner notes for the krautrock pioneers’ 1978 album Cannibalism). Homosapien, the album, ended up being electronic by accident, however.

Shelley had worked on a series of demos with producer Martin Rushent in anticipation of a fourth Buzzcocks album, all recorded with a new-fangled Roland MC-8 Microcomposer; a prototype sequencer. Rushent was keen to get out of producing punks and aspired to work with more genteel electronic acts instead, and so he shelled out a small fortune and built Genetic Studios, an air-conditioned barn equipped with a Fairlight, a Synclavier, some Roland synths and the fabled MC-8. Speculating to accumulate was a gamble that paid off for Rushent. The songs turned out good enough to release as they were. Crucially the recordings caught the attention of avant garde Sheffield outfit the Human League, who then pursued a more poppy direction on their third album Dare with Rushent at the helm. It went to no.1 in the UK and no.3 in America, spawned five hit singles including the no.1 “Don’t You Want Me” (on both sides of the Atlantic) and won Rushent a Brit for best producer in 1982. Shelley wouldn’t be nearly as fortunate.

The release of the album Homosapien was delayed in the UK until January 1982 because of contractual issues and the BBC ban meant the lead single would become a cult club classic but never the hit it richly deserved to be. It’s one of those moments that makes you wonder what might have been. The album too is littered with invention and indelible hooks. “Qu’est-ce Que C’est Que Ça” is a cosmic indie kaleidoscope of nervous energy, with parts leaping out at you in all directions; “Guess I Must Have Been In Love With Myself” is vintage Shelley, teetering on the edges of straight rock with swooping psychedelic production, it also veers close enough to “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” in the chorus to have made Holland–Dozier–Holland’s lawyers twitchy. “Yesterday’s Not Here” meanwhile sounds like a duet between the Kinks and Giorgio Moroder (a beautiful thing, obviously, and all the more poignant lyrically now Pete’s no longer with us), while the closing track, “It’s Hard Enough Knowing”, is a gorgeously weighted electronic waltz that traverses a tightrope slowly but elegantly in order to wring out all the tension.

Follow up XL1, also recorded with Rushent, faired little better, with lead single “Telephone Operator” (which is curiously reminiscent of Weezer’s “Hash Pipe”) landing outside the top 40. XL1, like all that went before it, showcased Shelley’s ability to write so many different types of song, whether its the ambulatory bass and “Black Skinhead”-esque chugga-chugga of “What Was Heaven?” or the stomping, immediate “(Millions of People) No One Like You”.

In 1986, Shelley went into the studio with Stephen Hague, a producer whose guiding influence worked wonders with both New Order and the Pet Shop Boys. The mix of Shelley and Hague is intoxicating here too, but again the record was criminally overlooked. The tracks are great right from the off: the intrepid “Waiting For Love”, the dashingly emphatic “On Your Own”, the impossibly good and impossible to nail down “They’re Coming For You”, the doomy and disco-y “I Surrender”… if success had eluded Shelley then it certainly had no impact on the quality of his oeuvre. The Heaven and the Sea is confident and accomplished but it’d be his last dalliance with a major label, and it effectively ended his solo career.

There was room for another experimental album in 2002, recorded with his erstwhile Buzzcocks bandmate Howard Devoto under the collective moniker ShelleyDevoto. Buzzkunst features the excellent “Can You See Me Shining?” among other pearlers. But perhaps best of all is a 1984 techno track Shelley demoted to a B-side, but which found exposure through an unusual source. “Give It To Me” is an exuberant five-and-a-half-minute dancefloor stomper that was tucked away on the flipside of “Never Again”. It begins like “Blue Monday” and morphs into the Rapture at their most euphoric. A brief bridge roughly two minutes in was lifted from the record and used for the Tour de France coverage, which in the 1980’s was on Channel 4. It’s a masterclass in where to take a track with just a four-to-the-floor beat, some coruscating percussion and an array of delay pedals. Naturally most people didn’t realise Shelley had written the Tour de France theme, though recognised that it was a tour de force. That’s the problem with being self-effacing all the time; it just doesn’t seem to get you noticed.

You can find Jeremy on Twitter.